Benedict Arnold’s warehouse and fish stores on Campobello

Eastport Sentinel 1854

“The old wooden fish-stores that Benedict Arnold built at Campobello (on the English side), just opposite Lubec (on the American side) at the time when he was carrying on the smuggling business between St. John and this vicinity are standing yet, in good preservation. What a capital smuggler and deceiver, in both countries, Arnold must have been!”

Benedict Arnold’s wooden fish-stores, built by Arnold on Campobello in 1785 or 1786 were still in “good preservation” in 1854 and some years later when the above photo was taken. We have written previously about Arnold: a 2017 article titled “Benedict Arnold and the St. Croix Valley” by Lura Jackson can be found on our webpage as can an article I wrote titled “Bootleggers and Benedict Arnold”. Recently I have been fortunate to find in some old newspapers additional information about Arnold and his wife Peggy’s life Downeast. Here we will update the saga of Benedict Arnold’s adventures in the St. Croix Valley.

Benedict Arnold when a hero of the Revolution

I will make no attempt to summarize Arnold’s life from his birth in Connecticut in 1741 to his arrival Downeast in 1785. As a successful merchant and West Indies trader in his younger years, Arnold was both audacious and unscrupulous, traits which were a mixed blessing come the Revolution. As General Benedict Arnold he was perhaps the best general the Americans had but when he came to believe himself, not completely without justification, mistreated and unappreciated by his country, he had no scruples switching sides if the price was right. The Brits were ready to pay almost any price to Arnold for the surrender of the strategic fort at West Point which Arnold then commanded, and Arnold found the price right. Hence his name became synonymous with any sort of traitorous, treacherous, or disloyal act.

In September 1781 the plot to surrender West Point to the British was discovered and Arnold was forced to flee to British held New York. His wife Peggy and their young son were then in Philadelphia. Ironically Philadelphia was then held by American forces largely as a result of the military acumen and bravery of Arnold himself at the battle of Saratoga. General Washington graciously allowed Peggy and her son to join Arnold in New York from whence they sailed to their new life in England on December 15, 1781.

This new life in England was not at all what the Arnolds had envisioned. Initially all went well. The Arnolds were feted by London society and Peggy, a noted beauty, was presented to the Court on February 10, 1782. Soon however the luster and novelty wore off and there remained an undercurrent of distrust and even hostility to Arnold, especially in the military, for even though Arnold’s traitorous acts had benefited England, many found it difficult to like or quite trust a traitor to his country. This was especially true for the sizeable portion of English population which had supported the colonists demands for independence.

Feeling unwelcome in England in 1785 Arnold purchased a brig and leaving his wife and family in London sailed for New Brunswick, specifically St. John which was then home to 14000 Americans who had fled America during the Revolution and remained loyal to the English King. They were called Loyalists and the city to this day is known as the Loyalist City.

Arnold probably thought the town folks would better appreciate his sacrifices for England than had Londoners and it is possible this would have come to pass had newly minted Loyalist Arnold not had the same personality and lack of scruples of the American Arnold. He was soon embroiled in business disputes with the locals.

From the St. John Telegraph 1885 history of New Brunswick shipbuilding.

Shipbuilding Industry – The first vessel constructed above the Falls was built for Benedict ARNOLD by Nehemiah BECKWITH, the great grandfather of J. Douglas HAZEN, M.P. Mr. Beckwith failed somewhat (a day or two) in his contract for the time of launching and Benedict Arnold refused to accept the vessel except at a ruinous reduction. Mr. Beckwith had to accept Arnold’s terms greatly to his injury. It was a mean advantage.

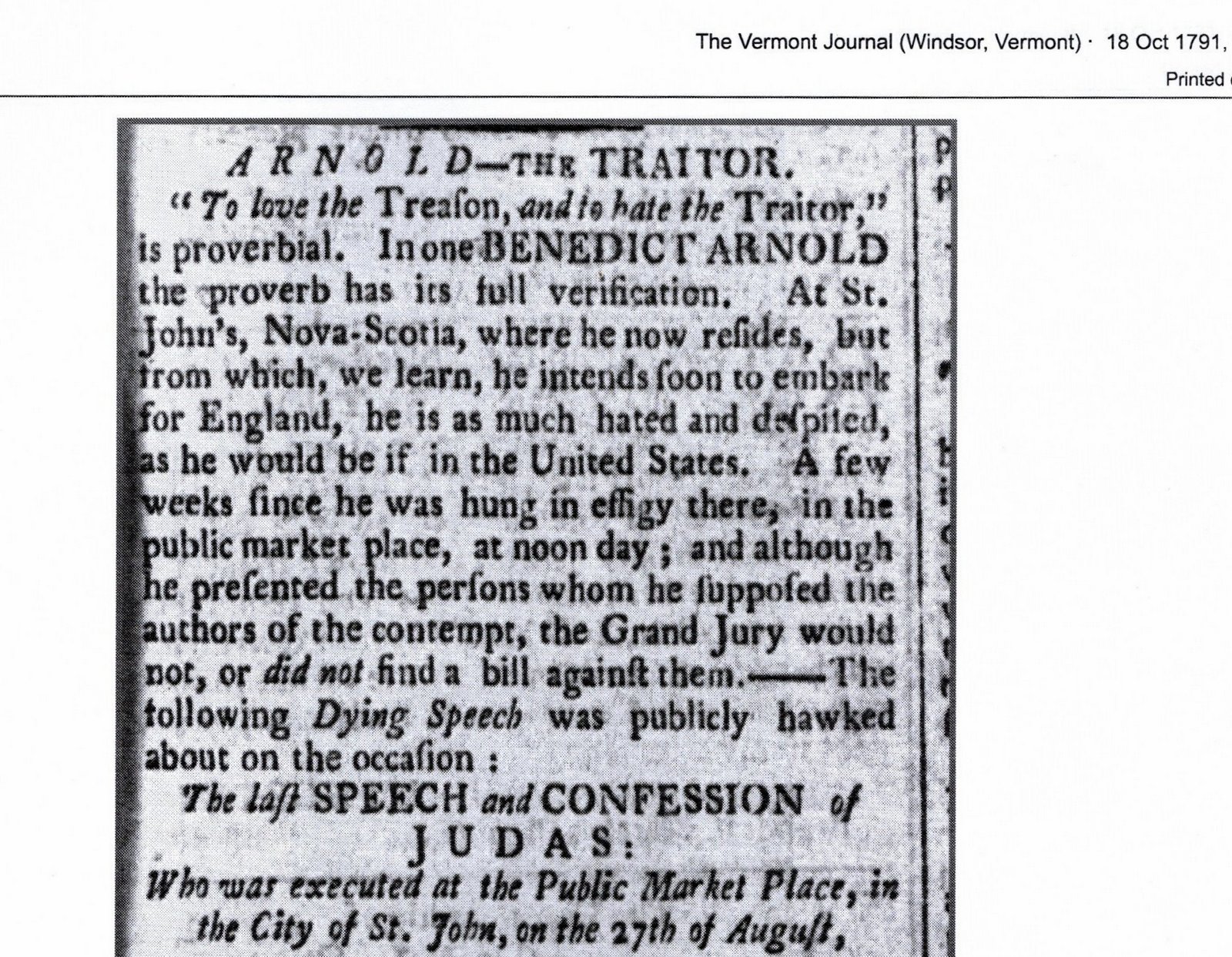

Arnold had a habit of taking a “mean advantage’ of Loyalists in St. John. He was so unpopular he was once hanged in effigy by the citizens who thought him not only a too sharp businessman but dishonest. According to the Evening Morning News of St. John (1855):

Persons are still living at Saint John who resided there when Arnold’s store was burned. The impression was, and still is, the fire was caused by design for the purpose of defrauding a company in England that had underwritten the merchandise it contained to an amount far exceeding its worth.

One person who accused Arnold of being responsible for the fire was sued by Arnold for slander and Arnold actually won the case. The court awarded him a few shillings in damages, more a rebuke than a victory.

Arnold’s Home overlooked Friar’s Head and the Bay

It was probably while his wife was still in England that he began trading and smuggling Downeast. His prior experience as a young man with the Indies trade made him a perfect fit for life Downeast after the Revolution. Passamaquoddy Bay was then the only point of contact on the Atlantic Ocean between the new minted United States and the British Empire in an era when all trade was by sea. Trade directly between the United State and the British Empire was difficult if not impossible for political reasons but embargoes and duties were largely ignored Downeast and vast quantities of goods flowed back and forth across Passamaquoddy Bay and thence onward to other destinations.

The home of Benedict and Margaret (Peggy) Arnold on Campobello

Arnold bought or possibly built the large house on Campobello shown above. We know he had many contacts with Americans, sometimes on the American side where a warrant for his arrest was outstanding. Had he been arrested he no doubt would have been hanged. Still he was brazen enough to make overtures to some of the soldiers with who he had served during the Revolution but was rebuffed.

Colonel John Crane , a participant in the Boston Tea Party, had served with distinction during the Revolution and settled near Lubec. In 1786 Arnold was in Passamaquoddy Bay aboard the Lord Sheffield, the vessel he had acquired so cheaply in St. John, and invited Crane to dine with him. Crane is claimed to have replied “Before I would dine with that traitor, I would run my sword through his body.”

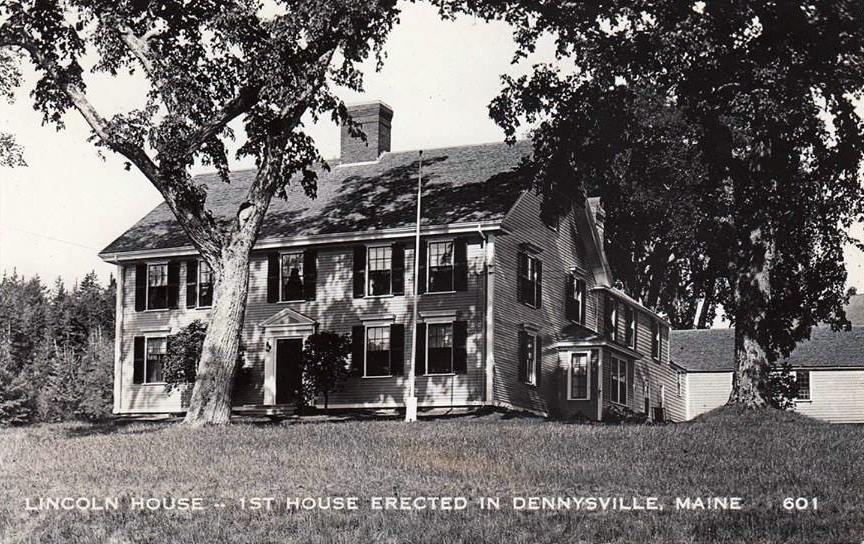

General Benjamin Lincoln’s house Dennysville

General Benjamin Lincoln who built the Lincoln House in Dennysville and who may have been the only American present at the three major British surrenders of the Revolution-Saratoga, Charleston and Yorktown, had a similar experience. Arnold’s servant came to the Lincoln House to suggest that Arnold and Lincoln make peace and dine together. General Lincoln’s answer was much the same as Colonel Crane’s.

The most poignant account of a former soldier meeting Arnold, although Arnold himself was not aware of the meeting involved John Shackford who served with Arnold on the heroic but ill-fated attack on Quebec during the Revolution. John Shackford settled in Eastport after the war, being one of the first inhabitants of the town. Both Shackford Street and Shackford Head are named for him.

From Bangor Historical Magazine 1887:

While at St. John, Arnold loaded vessels with timber at Campobello, opposite Eastport, and made his headquarters at Snug Cove, and it must have been at this time that he had dealings with Col. Allan. Capt. John Shackford, who was one of the original settlers of Eastport served as a soldier under Arnold in that terrible march through the Maine wilderness to the walls of Quebec, and in spite of the want of sympathy which such a staunch patriot would have for such traitor always retained a kindly remembrance of him. Once when Arnold was loading a ship at Campobello, he sent to Moose Island (Eastport) for men to help in the work, and Shackford was among those who went over for that purpose, and he used to relate that when at rest after his meals he frequently seated himself on the deck of the ship to watch the movements of his old commander for whom courage and military skill he still retained admiration. “Tears,’ he said, ‘sometimes came, and I could not help myself, he carried us through everything, and I could not help thinking of him as he was then.’ It is not remembered that he made himself known to Arnold, who soon after went from the neighborhood and removing from St. John to London, died there in 1801.”

William Swain was one of the first settlers of Calais and built a dwelling just below what is now the Milltown Bridge. In 1789 he relocated to St. Andrews. He became a merchant there and did business with Arnold who took a mortgage on one of Swain’s properties in 1789. Barnes’ history of Robbinston alludes to Arnold being a visitor to the town but this would seem to be a rather dangerous undertaking for a man who would certainly have hanged if apprehended on American soil. Still, we know he traded regularly with Col. John Allan who maintained a trading post on Treat’s Island in 1786 and 1787. Less than a mile away and in full view of Arnold’s home, Treat’s Island was U.S territory. During the Revolution George Washington had appointed Allan commander of all American troops in the area and Superintendent of Eastern Indians. Why Allan would do business with Arnold is a mystery but his account books which have been preserved show Arnold buying rum and lumber from him on several occasions. It does appear from the notations in the ledger that Arnold still owes Allan for these purchases.

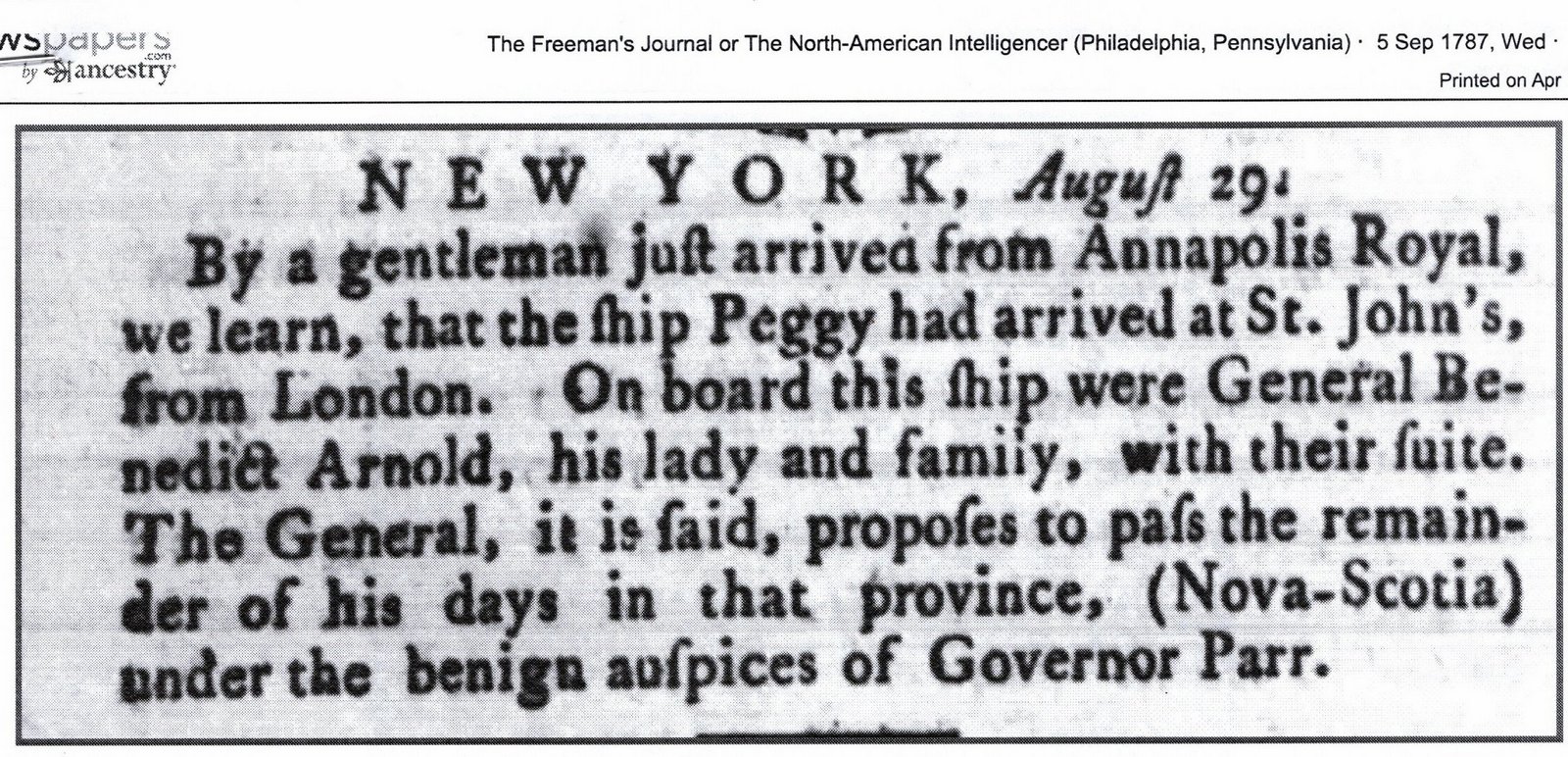

Arnold returns to St. John with his wife and daughter 1787

In 1787 Arnold returned to England to bring Peggy and his young daughter back to St. John. Peggy had been surprised to discover there was a new member of the family – a boy named John Sage, mother unknown, father Benedict Arnold. She was forgiving and accepted the child into the family but she was not happy in New Brunswick and thought it cold although that seems odd considering London’s notorious weather.

A 1903 article in the Cedar Rapids Iowa Gazette about Campobello titled “Where Benedict Arnold Hid” queries:

It is interesting to conjecture what must have been the life of this once gallant officer and his wife, the beautiful belle of Philadelphia, Margaret Shippen, in the wild and savage region. What longings to revisit his native land, to exchange his ill-gotten gains for the right to be the lowliest citizens of a country that he had tried to betray. But he soon grew tired of gazing across the turbulent waters of the channel to a land that had renounced him; so he left his lonely house for the still greater solitude of London, where no one would have aught to do with him. Even the loneliness of life on Campobello must have been preferable to the bitter scorn and contempt which he met everywhere in the world’s metropolis.

In 1909 the Lewiston Sun Journal published an article on Arnold’s life on Campobello.

From Lewiston Sun Journal July 31, 1909

A history of Campobello Island

For Americans, Campobello has a sinister meaning and significance. Here for many years was the exiled home of Benedict Arnold, a man whose name and memory will ever be execrated by all lovers of liberty and patriotism. Obliged to fly from the country he had betrayed, he was despised by the people of England whom he had sought to serve by his treachery. Finally, life became intolerable in London and he came here where he could live within sight of his native land on whose soil he no longer dared to set foot. Here he dragged out several years of his miserable existence and here the home on Friar’s head in which he lived has stood as a curiosity to sightseers until within a few years. The old cellar still remains to mark the spot of his exile and recall the most lamentable chapter in American history.

The house in which all lived was a large and somewhat pretentious mansion of the old type. It commanded a full view of Passamaquoddy Bay while the Friars head was a few rods away. The honorable George Pottle of Lewiston tells the writer that he visited the building a few years ago and was deeply interested in the place and its surroundings. No one can tell whether he purchased or built the house but certainly it was ample for all his wants. Mr. Pottle speaks of the wine cellar with the old decanters kept just as Arnold left them, and these tell the silent story that he sought to drown his sorrows in the cockpit of deep breaths but never cheers.

In this connection the writer once had a curious light thrown on the character Arnold. While lecturing in the village of Dennysville a few years since the landlord of the hotel showed him an old account book of his grandfather Alan who was a trader on the island of Campobello a century ago. In this book the name of Benedict Arnold appears many times and in nearly every instance the charge was for rum and molasses. He still closer inspection revealed the fact that many of these charges had never been settled, thus proving that the man who betrayed his country was not above the meaner vice of cheating his grocery man!

Just how Arnold passed his time here it is difficult to say. Tradition among the Islanders says that at one time he kept a small store in one of the front rooms of the house, but that his patronage was very limited. It is well known that the bluff old English Admiral Owen turned the cold shoulder to him in the same manner that the people of England did. Arnold was thus left without a country and without a friend. It is also said that on one occasion a party of bold spirits in Eastport attempted his capture by the kidnapping process. On a dark and stormy night they rode across the Bay and landing close to the house try to gain admittance. Suspecting something of the kind Arnold was ready to receive them with gun and saber and so determined was his resistance that the would be captors were obliged to retreat. Had they succeeded in capturing and taking Arnold to America’s soil he would have been court martialed and shot, and with Napoleon on her back at the time it is safe to say that England could not have successfully interfered.

After living in his Campobello house a few years life became intolerable to him. He removed to Saint John. From that time on the building passed through several hands. It was finally burned only 10 or a dozen years ago. The writer succeeded in finding a photograph of the old building and also took a picture of the cellar and spot as it is today, the cellar is choked with bricks and rubbish but the well in one corner still be seen though filled with black and stagnant water. Both of these pictures appear in halftones on this page and we’ll prove a melancholy interest to all who are familiar with this most discreditable chapter in our national life.

In fact, Arnold spent only a couple of years in Campobello before returning to St. John where it seems he continued to be unwelcome. Finally in 1791 he sold nearly all his property and possessions and left for England. American newspapers rejoiced.

American newspapers rejoiced in Arnold’s business and personal problems

Life in England did not improve. In 1792 Lord Lauderdale made a slighting remark about Arnold in the House of Lords and Arnold challenged the lord to a duel. Arnold fired first and missed. In one version of the story the lord raised, then lowered his pistol remarking “I’ll leave you to the hangman.” Other more credible accounts report the combatants parlayed and came to understanding. Whatever the truth Arnold soon took again to the sea, privateering against French ships in the West Indies and acting occasionally on behalf on the British government. When he died in 1801 at age 60 his financial situation was dire, and he left his wife Peggy with little. She died three years later at the age of 44.

There were still fortunes to be made in Passamaquoddy Bay. By 1801 huge quantities of plaster were being smuggled from New Brunswick to Eastport with American flour going the other way, much being reshipped across the oceans.

George Leonard, New Brunswick’s Superintendent of Trade and Fisheries and a prominent Loyalist, became greatly alarmed by the proceedings in the vicinity of Moose Island. He described the Americans in the area as a “lawless rabble” and claimed that the bay and islands were the asylum of deserters from the British army and navy and of criminals and absconding debtors from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Arnold would have fit in perfectly.