This article was originally published in the Calais Advertiser on April 20th, 2017. It is re-published with permission from the editor. Photos from our April presentation have been added.

Benedict Arnold and the St. Croix Valley

By Lura Jackson

“When you think of Benedict Arnold, what’s the first thing that comes to mind?” asked Al Churchill at a meeting of the St. Croix Historical Society on Monday, April 4th.

“Traitor!” The crowd unanimously shouted back.

Indeed, Benedict Arnold is the archetypal American traitor, having notoriously attempted to hand West Point over to the British during a defection to the British side. Not everyone knows the full story of Benedict Arnold, however, including the fact that during his time as a fugitive from the American government, he did a lucrative trading business in Passamaquoddy Bay.

Before becoming a traitor and a fugitive, Benedict Arnold was “unquestionably the best General we ever had, on both sides of the war,” said Churchill. “Without him, we probably wouldn’t have won the Revolutionary War.”

When the country was still a British colony, there were very few skilled military leaders or munitions available to stage the rebellion. Through Arnold’s talent with strategy and his bold bravado, he successfully rallied the troops on several occasions to demonstrate that America was not a lost cause.

The first victory of the Revolutionary War for the American side came at the hands of Arnold at Fort Ticonderoga, and important fort that gave access to Canada. Arnold had raised a militia and successfully captured the fort and all of its artillery, which were hauled back to Boston.

Benedict Arnold was instrumental in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga – representing the first American victory in the Revolutionary war.

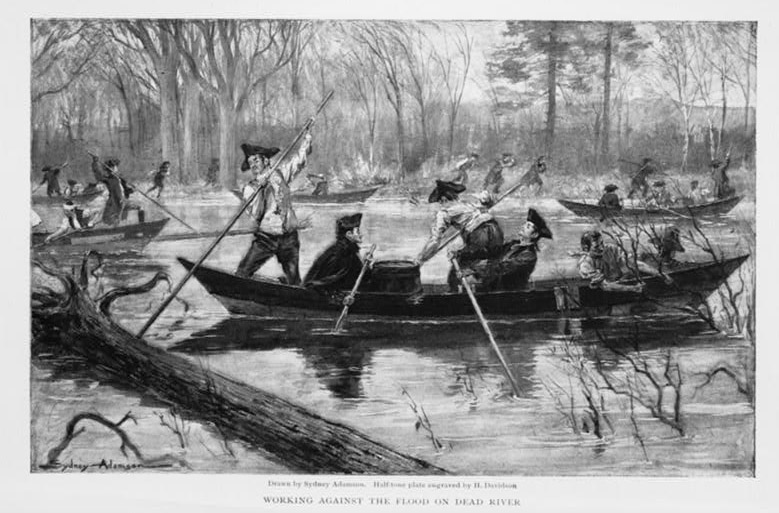

Arnold also led the infamous “March Through Maine” wherein he and his troops traveled from Gardiner up the Kennebec River with the intention of traveling straight through to British-held Quebec City. Arnold’s march began in the fall and continued through the winter. By the time he and his troops arrived, they were mostly frozen, starved, and out of ammunition, with half of the men having perished or left along route. Arnold, though, went the whole length of the river and still managed to briefly hold part of the city before being ousted when the second group of Americans (led by Daniel Morgan) that had been anticipated to assist in the attack failed to make a good showing. Arnold was shot during the siege, but was undeterred from participating.

“It was clear he was a born leader,” Churchill explained. Arnold had a famously difficult personality, making ten enemies for every one friend, and this contributed to a general animosity towards him from others in the military. Some accused him of fabricating the costs of the March Through Maine, alleging that he did not provide all of his receipts, an accusation that nearly made him leave the Revolutionary Army on the spot.

After the fairly disastrous March Through Maine, Arnold scored another major victory at Saratoga. While General Gates was in command of the Revolutionary Forces, Arnold acted against his orders and proceeded to rally the troops by riding up and down in full view of both sides brandishing his weapon – a brazen act that earned him a bullet in his boot. By doing so, he and his men were able to capture Breymann Redoubt, a critical point to put up artillery. With that victory, the French agreed to enter the war on behalf of the rebels, and the dream of America became that much closer to a reality.

Also at Saratoga was a local boy – William Vance, among the earliest settlers of Baring and the first to raise a mill there. Vance was notoriously patriotic, having erected a cannon and pointed it at Canada during the War of 1812, threatening to blow up any British that could be seen approaching.

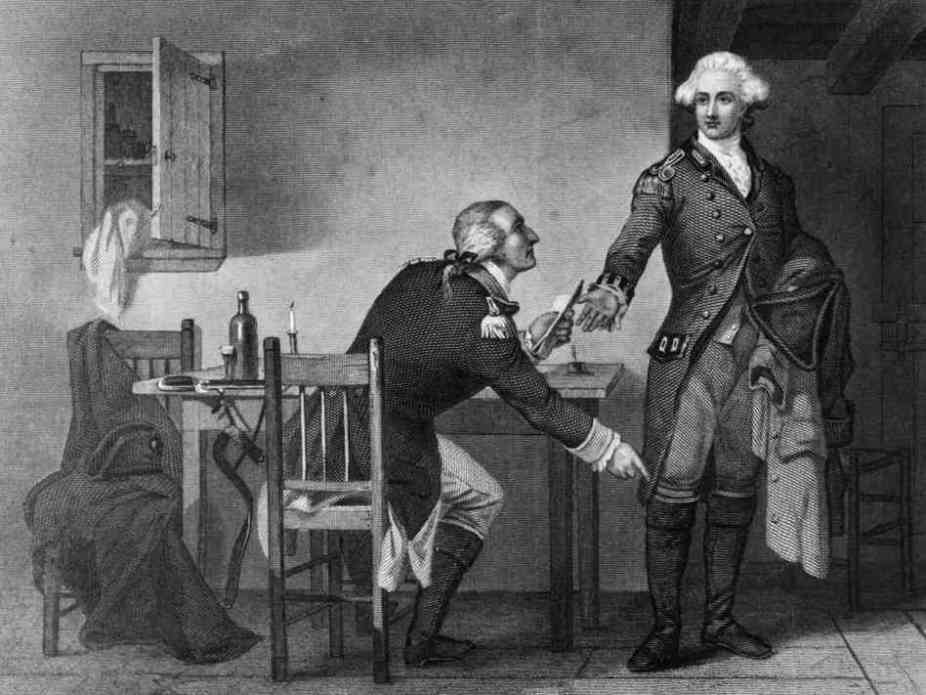

After Saratoga, Arnold was promoted to General as well as Governor of Philadelphia, but here is where his story begins to go more awry. Arnold had expensive tastes and an expensive young wife, and his finances plagued him. He successfully lobbied to become Commandant of West Point, an important fort that gave access to New York. Once there, he wrote a letter to the British offering to sell them West Point for 20,000 pounds (around $3 million in today’s money). The British accepted and sent a representative to complete the transaction. The boat that the British officer traveled on had to turn back before he could board it, and Arnold encouraged him to dress in plainclothes and sneak back to British territory. He fatefully agreed – and was soon captured and hanged as a spy. At the time of West Point being handed over, there was another local soldier present – one of the Boyden boys of Boyden’s Lake fame.

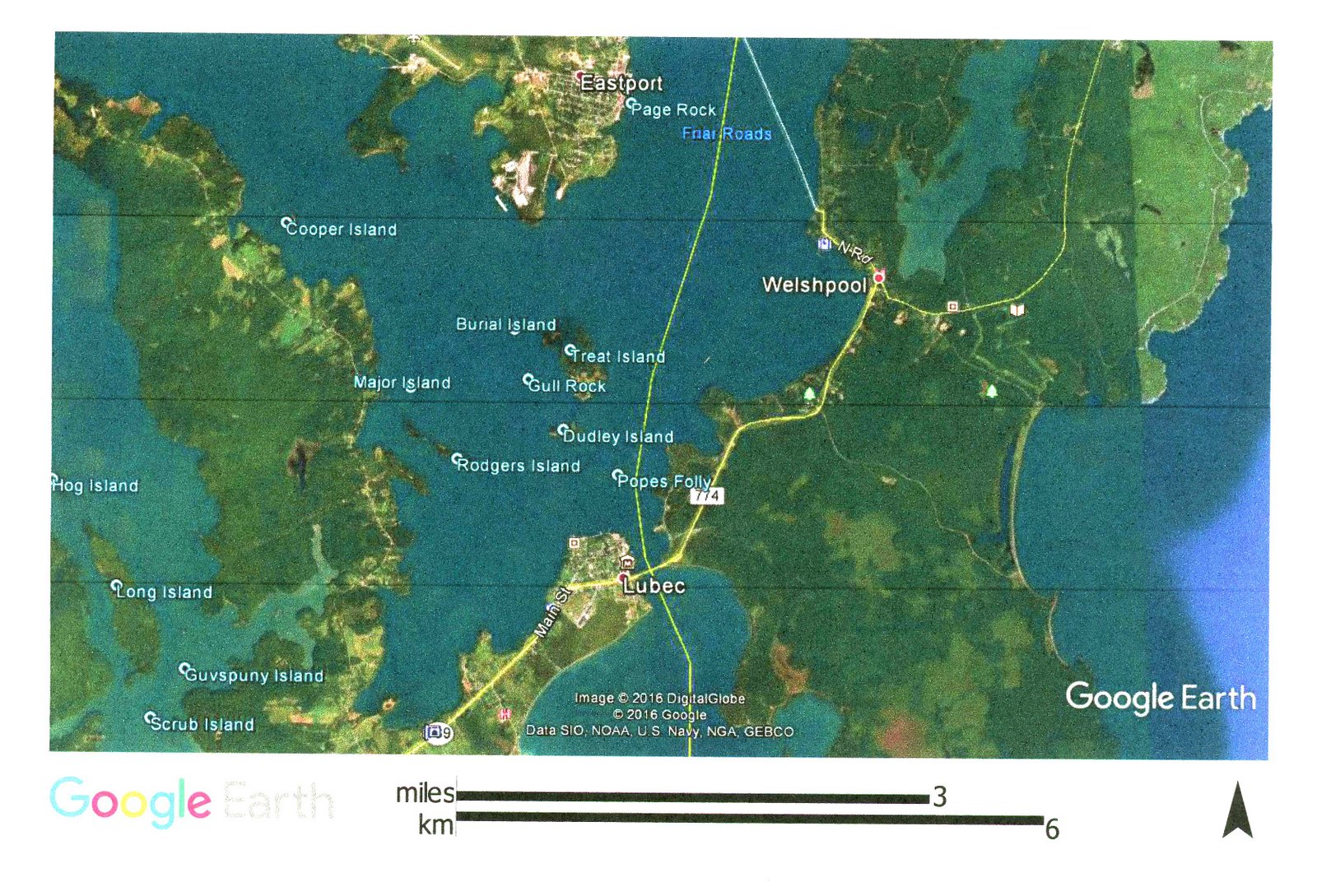

Arnold immediately fled, making his way northward through Machias to St. John. He traveled to England for a time before returning to St. John where he began a lucrative smuggling trade based in Snug Cove, Campobello. Arnold built a sprawling building to conduct his trades, though no evidence of it now exists. Accounts exist in Dennysville, Treat’s Island and Eastport of trades conducted with Arnold.

At the time, Passamaquoddy Bay was the epicenter of smuggling between America and Canada. “It was how people made their living back then,” Churchill explained. Some fished, but, “You’d make a lot more money smuggling 100 barrels of flour to St. Andrews than you could in a whole year of fishing.”

Arnold, of course, was thoroughly disliked by those he interacted with. At one point another trader was so incensed he lifted up a log and went after Arnold before his comrades held him back. “But for this, I would not have left a whole bone in his skin,” the man said.

Not everyone maintained animosity toward Arnold. Jack Shackford of Eastport – one of the first settlers in that town – served under Arnold during the fateful March Through Maine. As a result of his service with Arnold, he always felt kindly toward him, remembering his ability as a leader. It was this disposition that prevented Shackford from arresting Arnold as a traitor.

For several years, Arnold did a roaring business in smuggling before returning to London where he eventually passed away. “Certainly, he was a traitor, but without him, the Revolutionary War would have turned out differently,” Churchill concluded.