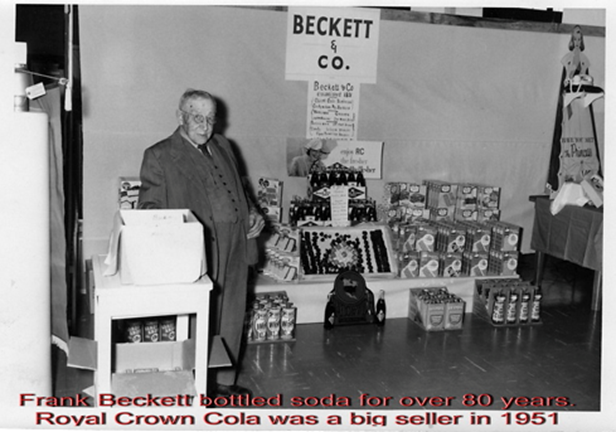

For anyone growing up in Calais in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, Beckett & Company was the store on Main Street where a kid could buy molasses gems, honey sticks and broken fragments of chocolate by the ounce at a very reasonable price. In fact, many can blame their addiction to chocolate on Dave and Phil Beckett, Class of 1965, who occasionally worked at the store and were quite generous when reading the candy scales. Most didn’t know and certainly wouldn’t have cared that Beckett & Co. was probably the oldest business in Calais in the 1960s and possibly the St Croix Valley other than The Calais Advertiser and St. Croix Courier and while it started as a “confectionary” in 1851, it became much more than a candy store. From the early 1900s Beckett and Co. was the primary wholesaler for nearly 150 neighborhood stores from Eastport to Vanceboro, bottling nearly all of the Nehi, Royal Crown Cola, and cream soda consumed in the area and employing up to 30 people. If you bought a pack of Chesterfields, a can of corn, a cake mix, or a jar of pickles from the neighborhood store, it had almost certainly been delivered from the Beckett warehouse on Union Street in a Beckett and Co. truck.

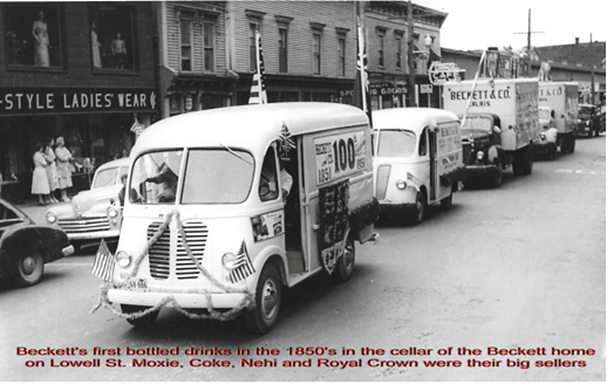

Frank Beckett bottled soda for over 80 years. Royal Crown Cola was a big seller in 1951

Many will have a vague recollection of occasionally seeing a very old gentleman, always in a suit, in the store. His aged appearance shouldn’t have been surprising as the gentleman was Frank N. Beckett, Sr. and he was born on August 6, 1862, just days before the Second Battle of Bull Run. At the time, he was approaching 100 but had been active in the business for almost 90 years. For most people Frank Sr. was Beckett and Co., a legendary candy maker, businessman, and civic leader but he was not the founder of the business. The story of Beckett and Co. begins a generation before Frank Sr. with his father, John G. Beckett and therein lies a tale, several in fact.

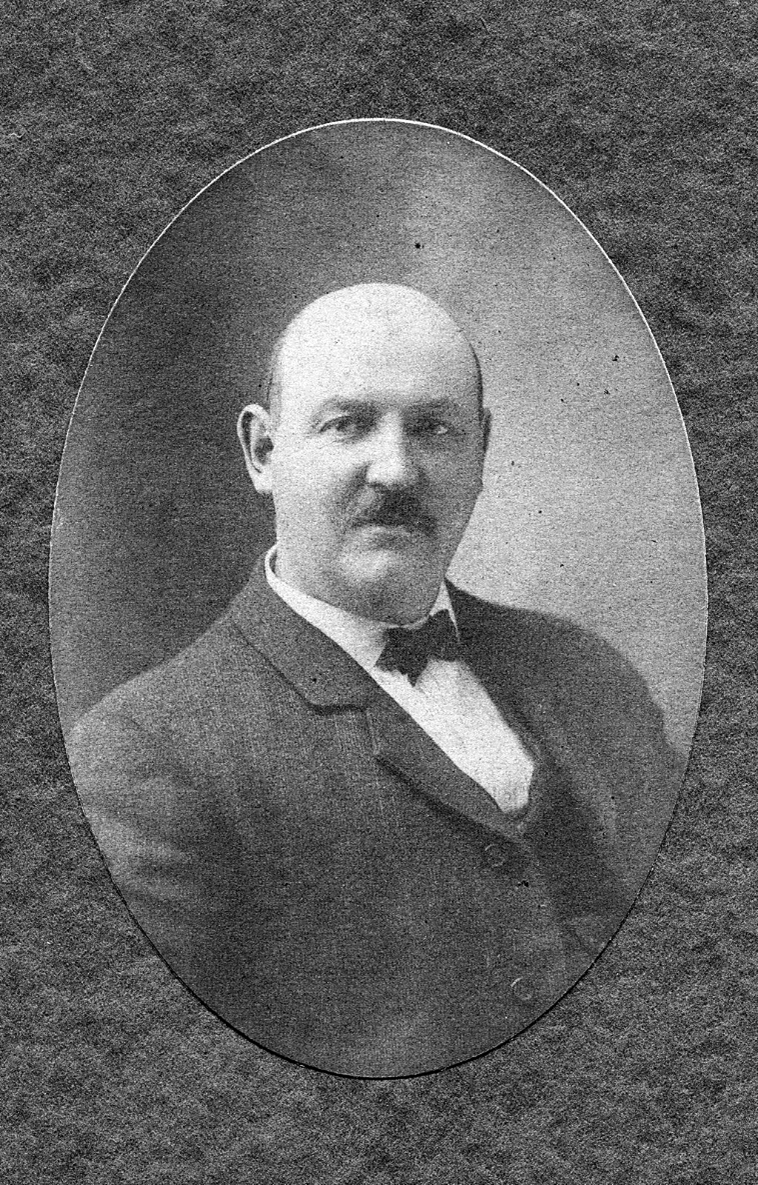

John Gregg Beckett, known as J.G. by his family, was born May 29, 1828 in Kilmarnock, Scotland and died in Calais, Maine on June 6, 1889. What happened between these dates, and what sort of person J.G. really was is somewhat a mystery. One could believe the St. Croix Courier’s obituary which claims he was unrivalled as a “public spirited and energetic businessman” whose memory “deserves a tribute more enduring than mere words” or one could credit family history which describes J.G. as a hard drinking, brawling rogue who was irresponsible in family matters and unscrupulous in business. A clue to the truth might be found in the Calais Times 1889 obituary which says of J.G., “He was of strong attachments and a brave opponent of all who excited his enmity, or had done him what he believed to be injustice.” Unusual language for an obituary, implying J.G. was a hard man who made his own rules. We suspect this is fairly accurate description of him.

His father, Hugh, was a confectioner. His mother, Helen, died a few days after John Gregg was born and J. G. was raised by Hugh’s second wife, Janet. The family moved to Liverpool in 1840 and J.G. learned the confectionery trade. In 1846 he decided to strike out on his own. His obituary in the Courier claims he had visited the United States as a young boy and being “favorably impressed” by the country, wanted to return. In 1846 J.G. landed in Boston by way of Turkey and Odessa and worked for a couple of years in a sugar house before moving to Eastport in 1850. He started a bakery in Eastport but in 1851 moved upriver to Calais where he opened a confectionery and bakery at the corner of Salem and Main, the present location of the Camden National Bank. In 1854 he married Mary Newton of Grand Manan and by 1860 had two daughters, Margaret Helen and Maud, and perhaps a son Frank W. who died in infancy, although we are not certain of this. This son is not to be confused with Frank N. the candymaker born in 1862. J.G. seemed to be well established in business by the late ‘50s. A piece in the Calais Advertiser on July 4, 1858 says:

“Mr. J.G. Beckett is making great preparation for regaling the public. He is making into confectionary no less than 5 barrels of sugar and is also making pies, cakes and pastries from as many as ten barrels of flour. And to wash it down he has any quantity of root, hop and ginger beer and also cold soda. To keep cool he has any quantity of ice cream. It takes JGB to do things up in shape.”

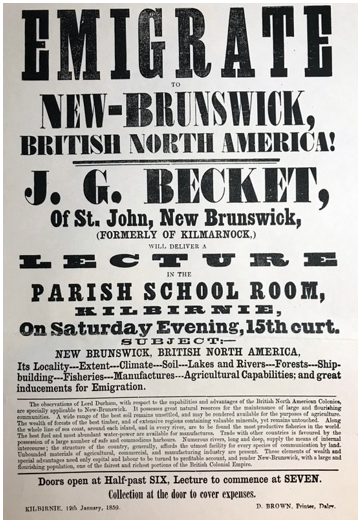

Within two months, however, on November 9, 1858, J.G. abandoned his business, left his family on Grand Manan and shipped out of St. John on the cargo ship Adept bound for Glasgow. The Glasgow adventure became a pattern for J.G. He often disappeared from Calais for lengthy periods on rather questionable ventures, leaving wife and family either in the care of others or to carry on the business in his absence. Family notes say the Scotland trip was to visit his family but, in truth, J.G. was looking to make a buck. A journal of the trip shows J.G. spending some of the trip studying the history and economics of New Brunswick in preparation for recruiting immigrants to New Brunswick. At the time Canada was desperately in need of settlers and was willing to pay recruiters by the head for anyone who could plow a field or swing an axe. J.G. saw this as a business opportunity and, billing himself a resident of and an authority on New Brunswick, where he had resided only briefly, he returned to Scotland to convince as many Scots as possible to return with him to paradise. The poster above titled “Emigrate to New Brunswick” advertised a lecture to be given by J.G. in Kilbirnie, Scotland on January 15, 1859. The claims about New Brunswick were fairly outrageous. The province, according to the poster, had the best soils, best fisheries, most abundant water power and the largest and most flourishing population of any place in the British Colonial Empire. In his journal J.G. rationalizes his venture as follows: “I hope I shall succeed in my present undertaking and that I may be successful in inducing many to make for themselves a comfortable home, and for their children a noble heritage in New Brunswick.” We doubt the prospective emigrants realized J.G.’s fund of knowledge about New Brunswick was largely obtained by reading agricultural reports during his four-week sea voyage.

We know he was successful in finding at least one Scot to emigrate—his half-brother Alexander. Alexander returned with J.G. to St. John in 1860 and eventually settled in Eastport where he also established himself as a confectioner. Alexander was the patriarch of the Eastport branch of the Beckett family. Many may remember Harold G. Beckett, a prominent citizen of Eastport whose son, John may be the last surviving member of Alexander’s line. J.G. spent about a year in St John after his return and his daughter Maude was born there on March 19, 1860. Maude became well known in Calais as a businesswoman who operated a fine goods store for many years just up the street from Beckett and Co. She also taught for years in the small school near the corner of High and Monroe streets.

By 1861 J.G. had returned to Calais, and according to the Advertiser

“. . . has taken up the building occupied by Geo Cole and fitted it up in first rate shape for the manufacture and sale all kinds of confectionary, pastry, ice cream, beer, etc. Mr. B is the finest caterer for the public palate this side of Boston.”

Frank N. Beckett was born in the store on August 6, 1862. Three years later, on December 12, 1865, Frank’s brother and future business partner, John G. Beckett, Jr. was born. When the boys weren’t in school, they were working in the family business. According to Frank he was a professional baker, candy maker, and bottler by the age of 17 who “understood the manufacture of beverage syrups and ginger and root beer, the generation of carbonic acid gas, the charging of soda tanks, etc.” Frank says he worked in the business without pay until he and his brother bought the business in the 1880s.

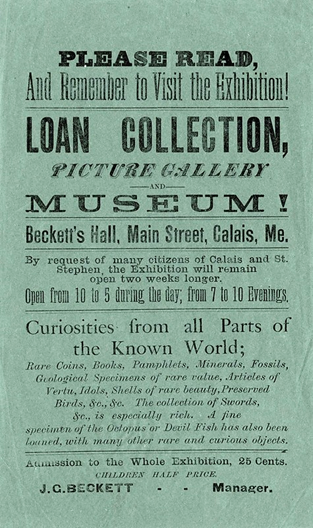

J.G.’s frugality may have had to do with the precarious state of the business. In 1870 the Beckett and Co. store was in a large wooden block where the Schooner is now located; and while J.G. continued to bottle soda and produce confections of high-quality, times were often hard so he tried his hand at operating a museum in what he called “Beckett’s Hall.” The museum displayed “Curiosities from all Parts of the Known World”—including “Rare Coins, Books, Pamphlets, Minerals, Fossils, Geological Specimens of rare value, Articles of Vertu, Idols, Shells of rare beauty, Preserved Birds, &c., &c. The collection of Swords is especially rich. A fine specimen of the Octopus or Devil Fish has also been loaned, with many other rare and curious objects.”

Admission was 25 cents but the wooden block was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1870 and J.G. relocated to a temporary stand on the old post office lot.

Photo dated 1872 – sign features Laughton Dentist on the corner of the building

In 1871-72 he and others built the “Palladian” brick block pictured above (now occupied by The Schooner and Karen’s Diner) on the site of his original store, but he couldn’t pay the mortgage and lost the property. The bottling business was then being carried on in the basement of the family home at the corner of Monroe and Lowell streets and J.G. was having difficulty finding a permanent home for the store. According to his obituary he “. . . invested largely in real estate and erected some of the fine brick blocks which now adorn Main St. These did not prove profitable and Mr. Beckett lost heavily by them.”

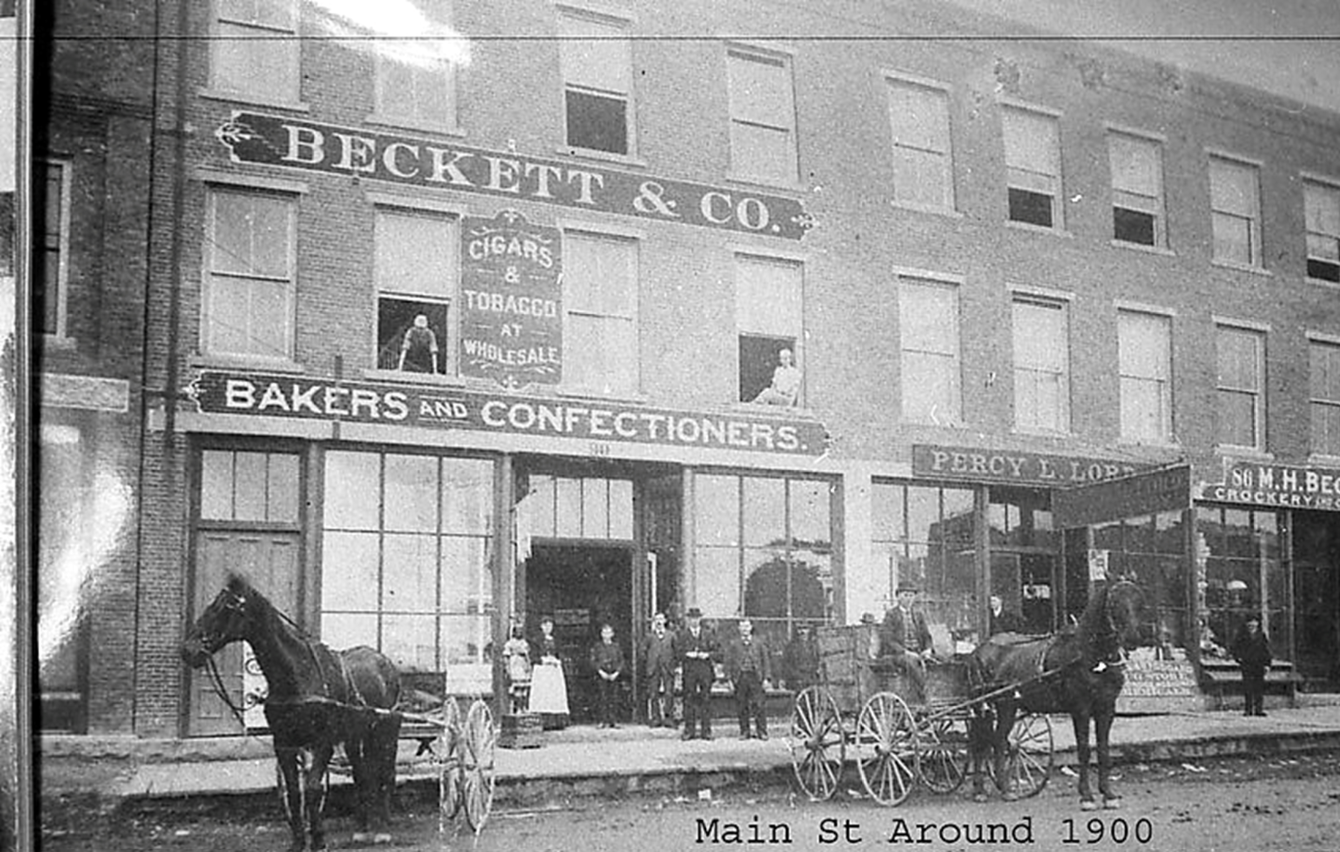

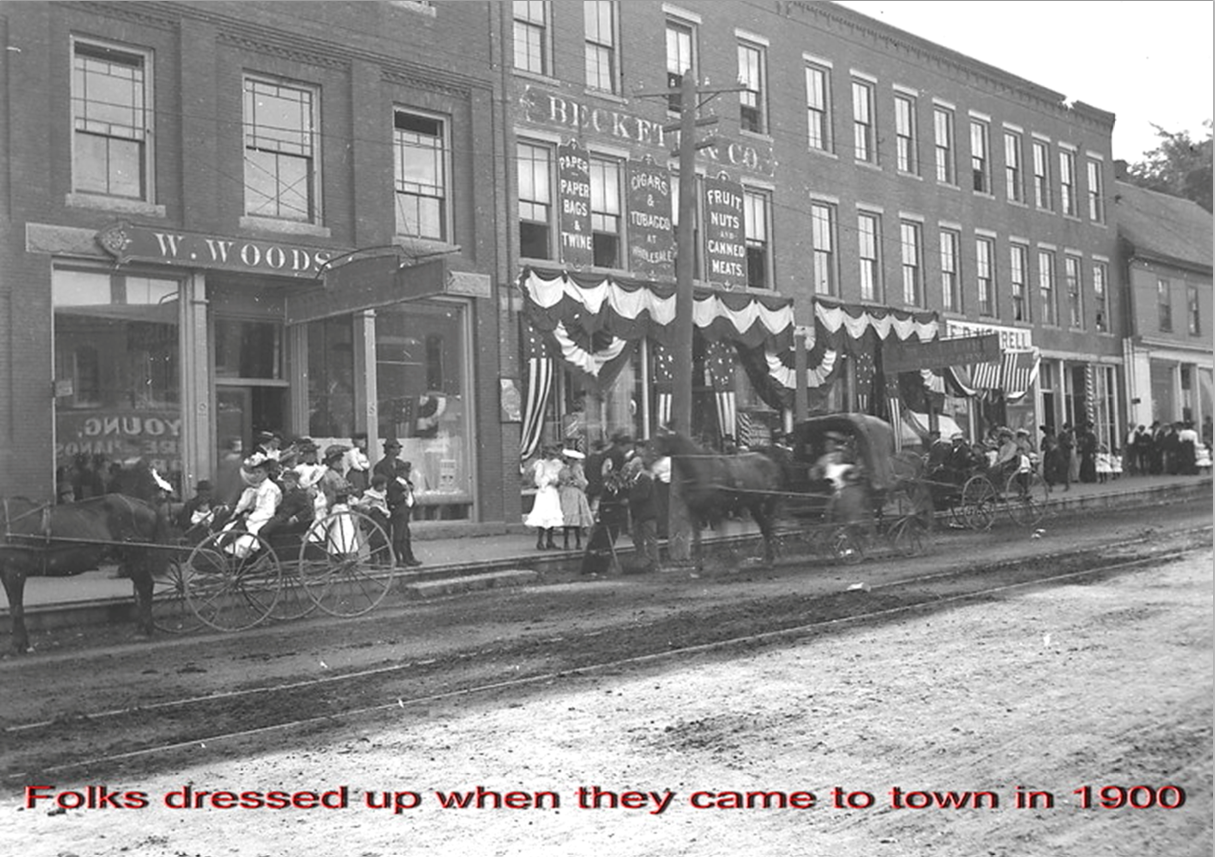

In the mid-1870s J.G. may have built part of the brick block which became the Calais Federal Bank and occupied it for a time, but by the late 1870s J.G. Beckett had constructed and finally found a permanent home for his business, the building at 139 Main St. pictured above, which remained the home of Beckett and Co. for nearly 100 years. According to ads in the Advertiser the business sold

“toys, cigars, fancy goods, bread, cake and Home Made candies from pure sugars and fancy confectionery of every conceivable shape.”

However, the life of a small businessman in Calais in the 1870s was easily as difficult as it had been in the 1850s. In 1879 Beckett and Co. is not even listed in the Calais Business Directory; and his son Frank, Sr. says the early years were sometimes not good times for the business, which may explain why J.G. became an arms dealer, decided lawyering might be a way to make a quick buck, was a hero of the Great Boston Fire of 1872 and, with his half-brother Alexander, embarked on a mysterious enterprise.

We know from his 1859 Scotland adventure that J.G. was not one to sit idly at home when money could be made with a bit of initiative. According to family history one such chance occurred during the Fenian uprising after the Civil War. In April 1866 Fenian invasion fever was at a high pitch on the border as our neighbors across the river in New Brunswick prepared for an onslaught of Irish revolutionaries who intended to establish an Irish republic in the province. J.G. saw a business opportunity and purchased a large number of civil war surplus Springfield rifles, some say a full railcar, at a very low price, probably because they were defective. The Canadians across the border were in a panic and, having very few firearms, were willing to buy almost any firearm, even civil war castoffs. J.G. was happy to oblige and to encourage our English friends across the border to part with $5, the price of the rifles. He and his friends set fires along the U.S. side of the river to simulate Fenian military encampments. While family history is often fiction, there is some corroboration for this story. There was an article in the Calais Times reporting the fires. It says in part: “The whole river was lighted up as though a mighty army was there to bivouac for the night… The men next began to fire shots from old fowling pieces… Calais people began ringing the fire alarms…. In St. Stephen, on the other side of the river, men, women and children were running through the streets. Word was sent over to them that Calais was filled with wild Irishmen, who would make an attack at daylight….”

It is not at all unlikely that J.G. participated in or even instigated this bit of theater. His grandson, Philip N. Beckett says J.G. was one of the “Fenians” and his great-grandson, Philip W. Beckett, recalls seeing the unsold Springfield rifles in crates at the store at 139 Main St. when he was a boy. They were lost in a fire in 1937.

Given the uncertainties of the confectionery and arms business, and given J.G.’s considerable experience before bars of all sorts, it is not surprising he resolved to become a lawyer. According to family legend, his obituaries, newspaper and trade articles, J.G. decided about 1870 to go to Harvard to study law. He returned to Calais having attended the most prestigious law school in the country and opened a practice in the store on Main Street. The 1874 Calais Business Directory contains a listing for J.G. Beckett, Attorney, Main St., Calais. Frank Sr. writes:

“Father decided he would like to be a lawyer. He had considerable experience as a client, and possessed quite a fund of general legal knowledge. So he started for Harvard and was duly graduated from the Law School.”

Regarding his experience as a client, his great-grandson Philip W. says J.G. was known to strong-arm those who owed him money and this got him into considerable trouble. Philip speculates it may have been one of the reasons he went to Law School. If you contact Harvard they will claim to have checked and double-checked their very accurate and complete records of everyone who attended Harvard Law School from 1860-1890 and will assure you John G. Beckett never attended Harvard Law School. However, they would be wrong. Historical records obtainable online do show John G. Beckett as a student at the school in 1870 and his son Frank describes a journey his mother took to Boston to visit J.G. while he was attending Harvard. Frank said he had a bookcase his father purchased while at Harvard which belonged to Daniel Webster. Even so, J.G.’s legal education was acquired, it seems, primarily as a litigant; and other than his ad in the Calais directory in 1874 it does not appear that he had a general practice of law although the Calais census of both 1870 and 1870 lists his profession as “Lawyer.” In later years his chief adversaries in court were his sons.

There is other evidence he left Calais for nearly two years in the early 1870s. Not only was he attending Harvard in 1870 but we know he was in Boston in October of 1872 because Dave and Patsy Beckett have some very nice silver, including a large pitcher, on which is inscribed

“Presented to J.G. Beckett of Calais, Me by Boston Friends. Admirers of pluck and sharers in the benefits of the lightning express ox and horse teams during the Epizootic epidemic. Boston October 29, 1872.”

Family history, including an account of his son Frank says J.G. got the silver as a reward for being a hero of the Great Boston fire of 1872 when nearly 1000 buildings were burned in the commercial center of Boston. Many of the horses used to pull the fire engines and pumpers were sick with distemper and J.G., according to legend, went to New Hampshire and returned with several teams of oxen to save the day. Why he was in Boston on October 23, 1872 is not clear, but the reference to the oxen and horse teams would certainly give credence to the story. It appears Beckett and Co. remained in business in Calais during his absence as ads were still appearing in the Calais Advertiser and it was reported he sold his brick block to Horton in that year; but who was running the business is a mystery. Perhaps he decided after the sale to Horton to disappear for a time and do some lawyering in the big city. This would fit with another family story. According to this account J.G. and his half-brother Alexander decided one day to embark on an adventure. They duly cleaned out the tills of their respective businesses and vanished for about a year. No one in the family knew where they had gone or when they would return. However, return they did, with a ship full of furniture acquired under questionable circumstances. Phil Beckett, Jr. says Mary Anne Casey, now Quartermain, has some of the furniture in her home in St Stephen.

By the 1880s the business and J.G. were both in bad shape. J.G.’s problem, again according to family history, was alcohol and general dissipation. In fact, surviving family members say the older boys, Frank, Sr. and John Gregg, Jr. had their father declared incompetent and took over the business; only a court battle restored him to control. In 1886, Frank and J.G., Jr. bought out their father. Their mother, Mary Newton, had died the previous year, and J.G.’s health had deteriorated further and he died in 1889. This was the beginning of a new era for Beckett & Co. The partnership of sons Frank and J.G., Jr. transformed the business from a floundering confectioner and bottling operation to a substantial and profitable enterprise with sales of over a million dollars by the late 1930s. In 1951 Beckett and Company celebrated its 100-year anniversary and many of its delivery vehicles participated in the huge Calais sesquicentennial parade. Some are seen here on Water Street in St. Stephen. While it would be unfair to give J.G. much credit for the eventual success of the business, it would also be unfair to be too hard on the family patriarch. He was very typical of the businessmen who settled in Calais and St. Stephen in the early years: an immigrant, tough and independent with a fondness for liquor and a willingness to do whatever it took to get by. These men gave Calais a rough edge but they were also responsible for building a flourishing and vibrant international community on the St. Croix.