The village of Pembroke, probably late 1800s

In the late 1800s Pembroke was a bustling and prosperous community of nearly 2500. The above photo shows the town center about 1890.

From the 1850s until the mid 1880s Pembroke Iron Works was a going concern

The main industry in Pembroke for several decades had been the Ironworks, which employed many townspeople and not a few from neighboring communities. Pembroke in the 1880s also offered employment in its shipyards, was a commercial Center for the area and was prosperous enough to support two newspapers.

Two of the families living in Pembroke at the time were the Longmores and the Wrights. Where they lived, we cannot say for certain, but it is likely they lived in West Pembroke as there is even today a house known as the Longmore House in West Pembroke. We can say for certain that Warren Longmore, age 9 and Freeman “Freemie” Wright aged 8 were classmates and the closest of friends, seemingly inseparable even when not in school. When Warren shot and killed Freemie after school one day in early October 1880, the community was saddened and shocked by Freeman’s tragic death. Surely the townsfolk thought it was an accident and indeed the initial hearing in the matter before Judge McGraw of Eastport found the shooting to have been accidental. Warren was released and the community began the process of grieving the sad death of one of its children.

Philadelphia Enquirer 1880

Days later the community received a second shock when Warren was rearrested and charged with murder. Thence began a legal process which resulted in the unlikely and unseeming spectacle of a 9-year-old boy on trial for murder before a Washington County jury in Machias. It was a trial without precedent, before or since, in the history of American jurisprudence. Never before or since has a child below the age of 12 been tried for murder.

Why the case took the course it did we cannot say. There is some suggestion the parents of the deceased boy were well to do and exerted legal pressure on the authorities. The initial newspaper accounts of the shooting did raise legitimate questions about the circumstances surrounding the death of Freeman Wright. Warren Longmore gave a number of conflicting accounts of how he came to discharge the firearm into the face of his best friend and his action after the shooting were certainly callous if judged by the adult standards, but Warren was only nine years of age, confused and frightened after the shooting. His statements and actions after such a traumatic event should not have been judged by the standards one would expect of an adult. Still, he was to sit in the dock at Machias in January of 1881 as an adult on trial for murder, a trial presided over by a judge who knew neither the law nor compassion.

The first account we have from the Calais Advertiser was published just after the shooting and was based on information provided by the Eastport Sentinel:

Terrible Tragedy at Pembroke

A Lad of Ten Years of Age Shoots His Fellow Schoolmate

And Afterward Attempted To Conceal The Still Breathing Body In A Vault

Correspondence of Sentinel

Shortly before the hour of four, Friday afternoon, Warren Longmore discharged a shotgun, its content striking Freeman Wright, a school fellow only nine years of age, fair in the face, causing his death six hours after.

There being somewhat conflicting stories told, by those first at the scene of the tragedy, and by the Longmore boy himself, the only witness to the ending of the bright young life, makes it almost an impossibility for your reporter to give a definite or trustworthy description of the sad affair.

Of the many stories told by the Longmore boy, we have selected the following as being the most feasible. He says: “I saw a cat at the barn, I ran and got the gun from the corner of the room- the kitchen. Freemie did not want me to shoot the cat so he ran and closed the door, he being upon the outside standing upon the step, he kept opening the door partway, and seeing me holding the gun ready to shoot would close it again. He kept doing so some little while when I said “now the next time you open the door I’m going to fire.” Undoubtedly in some such way as above described, the little boy met his death, the shot marks upon the door prove conclusively that the gun was discharged from the interior and that the door was not full opened.

After the boy was shot, the amount of blood upon the doorstep would denote that he was picked up and carried away at once, the trail of blood leading around the corner of the house to the sink drain. The body was allowed to remain here for a few moments when it was carried to a water closet at the back of the barn, where the blood plainly denotes that an attempt to put the body into the vault was unsuccessfully made; failing in this he carried it around to the back, and getting a shovel or spade commenced either to dig into the vault or to make a hole to bury his victim- the former theory, we believe is our own, and the correct one- at this moment he was discovered by a neighbor who gave the alarm. The little sufferer was immediately conveyed to his home. Doctor Smith and Lincoln were immediately summoned but could not be of any service in saving what little of life that was remaining.

A postmortem examination was made by doctors Smith and Lincoln on Saturday. The town officers have been making an investigation. An inquest would have been held but the coroner could not attend on account of sickness. The procedure was of a private nature and will not be made public until there is a hearing of the case, which will not be for some days.

It seems strange that so much should be taken have taken place in plain sight of the highway when people are constantly passing to and fro. The next house to the Longmore house was only 15 or 20 feet distance with windows overlooking the yard where the tragedy occurred.

Don’t talk yourselves into the belief that the shooting of the little boy was anything but accidental. Be charitable.

The admonition by the Advertiser not to prejudge the case and to “Be Charitable” did not fall on deaf ears. Community generally believed the shooting was an accident and this continued to be the case throughout the proceedings.

Washington Hall Pembroke-site of Longmore’s initial hearing

The preliminary hearing was held on October 8, 1880, before Judge McGraw of Eastport.

Report from the Eastport Sentinel:

Pembroke

The Shooting Affair.

Examination of the Longmore Boy For Shooting Freeman Wright

The preliminary examination of Warren Longmore, for the shooting of Freeman Wright on Friday the 8th, was commenced at Washington Hall on Thursday afternoon before Justice McGraw. The prisoner was brought into court about 20 minutes past three accompanied by his father. He is a bright looking boy, small of his age, with light hair, blue eyes, fair complexion with red cheeks. He seemed in no way downcast, but rather to take an interest in all that has been said and done. The examination of the witnesses was begun at once, there being a large number. In many instances a great deal of contradictory evidence was given. Your reporter concluded that a verbatim report would be unnecessary so we will give merely an outline of the proceedings.

The postmortem examination was conducted by doctors Lincoln and Smith, developed the following facts: – there were twelve shot wounds in the face, three of the shots penetrated the brain, either one of which would have caused death. The right eye was shot out entirely in the sight of the left destroyed. There were shot wounds in the right hand, breast and shoulders.

John Bragdon, a neighbor, had heard the shot and went to investigate. He appears to have been the first adult on the scene and was to be an important witness at the trial. He testified as follows:

I first saw a hat and a large quantity of blood by the sink spout at the end of the L. I followed a trail of blood from there to the barn and around to the water closet, saw Warren Longmore standing in front of the door and asked him what was the matter? He said “Freeman Wright was shot. I said let’s go tell someone. He said, “Oh no, let’s bury him.” I saw Freeman Wright lying with his feet out of the door and his head in one corner. I followed Warry around to the barn, stood in the doorway and saw him take out something from overhead that looked like a spade. The witness then testified that “Warry seemed frightened and scared.”

John Longmore, who was Warren’s younger brother, then testified. Oddly, in all of the accounts of the case this is the one of the few times his name appears.

Joseph Longmore testified to the above, with the exception that the body had been removed to the back of the water closet, that he found his brother with a spade in his hands and he wanted him to help bury the boy. He tried to lift the body but could not. Missus Ross found the body and the boys as stated above but she could not lift the boy so-called help. Mr. Edward Finney came in and carried the little sufferer to a carriage. The Longmore boy told several persons that he and the Wright boy were sitting upon the banking by the sink spout, and a shot was fired from the river striking right in the face and that he fell on him.

At the hearing Warren Longmore testified to a version of the events which differed from the one he had originally given to the authorities.

I went and got the gun to shoot a cat, I was in a chair by the table, Freemy wanted to look into the gun, I told him to go away at two different times, I went to raise my foot to kick him when my thumb slipped from the hammer and the gun went off. Doctor Lincoln in giving his testimony said the shot from a fouling piece, to make such a wound, must have been 25 to 30 feet distant.

One of Warren’s original accounts and one more consistent with the evidence was that a stray cat had appeared in the yard, and he had gotten the gun to shoot it through the open door of the shed. Freeman objected and kept closing the shed door so Warren could not shoot the cat. Warren warned Freeman that the next time Freeman opened the door Warren was going to shoot, which he did, the pellets striking Freeman and not the cat. The Sentinel reported:

A large number of witnesses were examined, but a great deal of the testimony was contradictory. Exactly how Freeman Wright was killed will probably never be known. There is but one living eyewitness and it seems almost, if not quite, an impossibility for him to give any definite description of the manner in which the deed was done. The stories told by him thus far are very deficient and unreliable.

The Calais Advertiser was very impressed with Judge McGraw’s legal analysis and disposition of the case commenting:

We will not review the testimony in a case of such a painful nature, the result is alone important. We will simply give the decision of justice McGraw in full, just as it was rendered at the trial. It is an admirable paper, evincing close study of law and remarkable power of legal and logical analysis, which marks Mr. McGraw as one of the brightest young lawyers ever admitted to the practice at the Washington County bar.

McGraw’s written decision was well reasoned and thorough. He first reviewed the applicable law in the United States on the legal culpability of children for the crime of murder. It was clear from his legal review that the case before him was unique-no child as young as Longmore had ever been charged with murder in the United States. In fact, the cases in which the issue arose involved young teenagers and many courts had concluded even they could not be convicted of the crime of murder. In the end he avoided the legal issue altogether and concluded:

I must find first that the offence charge had been committed, and then have probable cause, not to suspect, but to charge the prisoner. It must be approved then, and I think not by the act itself, that the prisoner had the requisite guilty knowledge and guilty intent. The fact of an attempt to hide the body cannot prove this, since it is in evidence that the attempt was made after that part of the transaction which must be considered an accident- namely the shooting. If this shooting was an accident the attempt to hide the body would not make it a crime. There is not the slightest doubt in my mind that the shooting was an accident. Up to the time that the body was carried behind the outhouse there is no proof of any crime. After that the fact that the crime and the intent to commit it must be proved. The guilty act and the guilty knowledge and intent have not been shown sufficiently to create probable cause for charging the prisoner.

I would not err against the prisoner and against mercy. I must consider the act not as a terrible crime, but as a terrible and melancholy accident. The prisoner is discharged and may go without date.

Machias Courthouse where the Warren Longmore was tried before a jury for murder

As we know, the discharge was shortly followed by reincarceration and a retrial. Where he was held until January of 1881, we don’t know but in early January he was indicted by a Washington County grand jury, and his trial began the next day. The jury was not, of course, a jury of Warren’s peers; none were children. The trial was reported throughout the country with many newspapers describing the proceedings as “Remarkable” “Unique” or “Unprecedented”.

On January 11, 1881, the Portland Press Herald reported that the Defendant was arraigned, pleaded not guilty and the testimony began. The Herald summarized the testimony:

It seems that on the afternoon of October 8 the attention of neighbors was attracted to the Wright boy’s house by the discharge of a gun. John Bragdon who was the first to make an investigation found Longmore in the barnyard digging a hole while prostrate beside him lay the Wright lad still breathing. Longmore upon being questioned told contradictory stories. He said that he and Wright had attempted to shoot a cat that he held the gun which was halfcocked while Wright stood on the threshold of the door to prevent the cat from escaping; he set the gun down on the floor and by some means he knows not how it discharged directly in the face of Wright who received its charge of shot, two of which penetrated the brain. Realizing at once the horrible result of the shooting he determined to hide the body of his late comrade and before life was extinct dragged it from the house across the yard and behind the barn where the neighbors surprised him digging a grave.

The prosecution made much of the medical examiner’s testimony that in addition of the gunshot wounds to the head, the skull was fractured in two places and suggested that Longmore “after dragging the Wright boy’s body back to the barn discovered that Wright was not dead and deliberately struck him with the spade” to complete the horrid deed.

The bulk of the testimony in the case was taken on the second day of the trial. Many newspapers covered the trial and their summary of the testimony differed in several respects, but the Boston Post and Boston Globe reports seem the most complete and accurate.

In addition to much of the testimony given at the preliminary hearing there was testimony of an altercation between Longmore and Wright that day in school:

From the Globe:

Charlie Babcock, 10 years old, and Nettie Carlow testified: On the day of the accident prisoner was sticking pins into the Wright boy in school; Wright boy told the teacher and the prisoner shook his fist at the Wright boy, saying, “If I can’t lick you in school I can out; you’ll never tell the teacher on me again; I never done nothing to you;” but this was a sort of amusement among the boys and girls in school.

However, there was also testimony from the boys teacher:

Miss Pattangall, teacher of the school the children attended, testified: “Longmore was an ordinary boy, not so bright as some, but no worse in morals than many others. Both boys were fast friends and always played together. They were dismissed together at 3:30 o’clock pm the afternoon of the accident. I was a member of the school committee, and knew the boys a long time, and never knew of any cruelty of disposition.”

The parents of the accused, his former school teacher, playmates and neighbors were called to testify. The general summary of their testimony is to effect that the death of Wright was accidental.

These witnesses have an impression that no malice was entertained. Public opinion inclines to the side of the accused; that the act was not committed intentionally or with malice aforethought. Longmore’s mother was on the witness stand this afternoon.

The prosecution relied primarily on the testimony of his classmates cited above and on Longmore’s conduct after the shooting to prove the intent and malice required by law to prove murder. The blood on the spade was a focus of the prosecution case, the allegation being that Warren, seeing signs of life in Wright, struck him several times with the spade to complete his crime. The defense countered that the spade was bloody because Mrs Longmore had told Joseph, Warren’s brother, to clean up the privy where the Wright’s boy’s body had been dragged bleeding after the shooting.

Mrs Longmore, the prisoner’s mother, testified as to the age and disposition of the prisoner. Mr. Longmore, testified: When I first met the prisoner after the accident he could not speak from fright; ordered prisoner’s brother to clean up the blood in the privy; he look a spade to do so; next saw the spade in the barn on a pile of chips; several people had their hair cut in the barn: the hair was swept among the chips upon which the spade lay; there was no blood on the spade when Joe (the brother) took it to clean the privy; when I learned of the accident I took Warren and went to Wright’s to see Freeman. Mrs. Davis testified similarly to the last witness. Always knew Warren; never heard anything against him; when Joe took the spade there was no blood on it; when he brought it back it was covered with blood and dirt.

A large number of witnesses were next examined to prove that the blood was cleaned up with the spade. The line of the defense seems to be to admit the shooting and claim that it was accidental, relying on the prisoner’s extreme youth in relation to the supposed use of the spade. It has been proved that the hair on the spade was of different kinds, some of which was from Longmore’s cow, and the rest of several different colors. Much of the evidence is contradictory, the witnesses for the defense denying directly the facts stated by those for the State. During the afternoon the courtroom has been literally packed with spectators, mostly women., who are interested on account of the “bright little fellow who was the victim, and the unfortunate little prisoner who, whether acquitted or convicted, will be pitied for many years. The defense closed without examining the prisoner, considering him too young to undergo a strict cross-examination, and because his statement of the affair had been given by several others. Briefly, his story is that he sat in the dining room, opposite the door, holding a gun, waiting to shoot a cat out in the yard. Freeman went from the window to the door and stood there. The gun was half-cocked. The prisoner attempted to let down the hammer and put the gun away, but in doing so the hammer slipped and discharged the gun, shooting him in the head. He carried the body round to the privy to leave it there, while he ran for his father. He told different stories at the time because he was frightened and didn’t know what to say.

The next day, January 13th the Judge instructed the jury and not fairly according to news reports:

From the Boston Globe:

The general opinion is that the judge’s instruction was strongly against the prisoner. After the Jury retired the prisoner began looking about the room in a composed manner. He did not seem to know what it all meant, and probably does not know the duties of the jury and judge. The charge was a great source of satisfaction to the Wright family and their friends, who seemed very anxious for conviction. As the judge’s remarks became stronger against the prisoner, those who had been busy in hunting up evidence against him assumed a joyful expression, as if they already had their little victim in their power. The county attorney, however, who only performed an unpleasant duty, exhibited no such feeling, and doubtless would be satisfied with an acquittal.

The judge had also commented to the jury that “The evidence tends to show that the wounds were caused by a spade and prisoner had a spade” even though this was one of the most disputed contentions in the case.

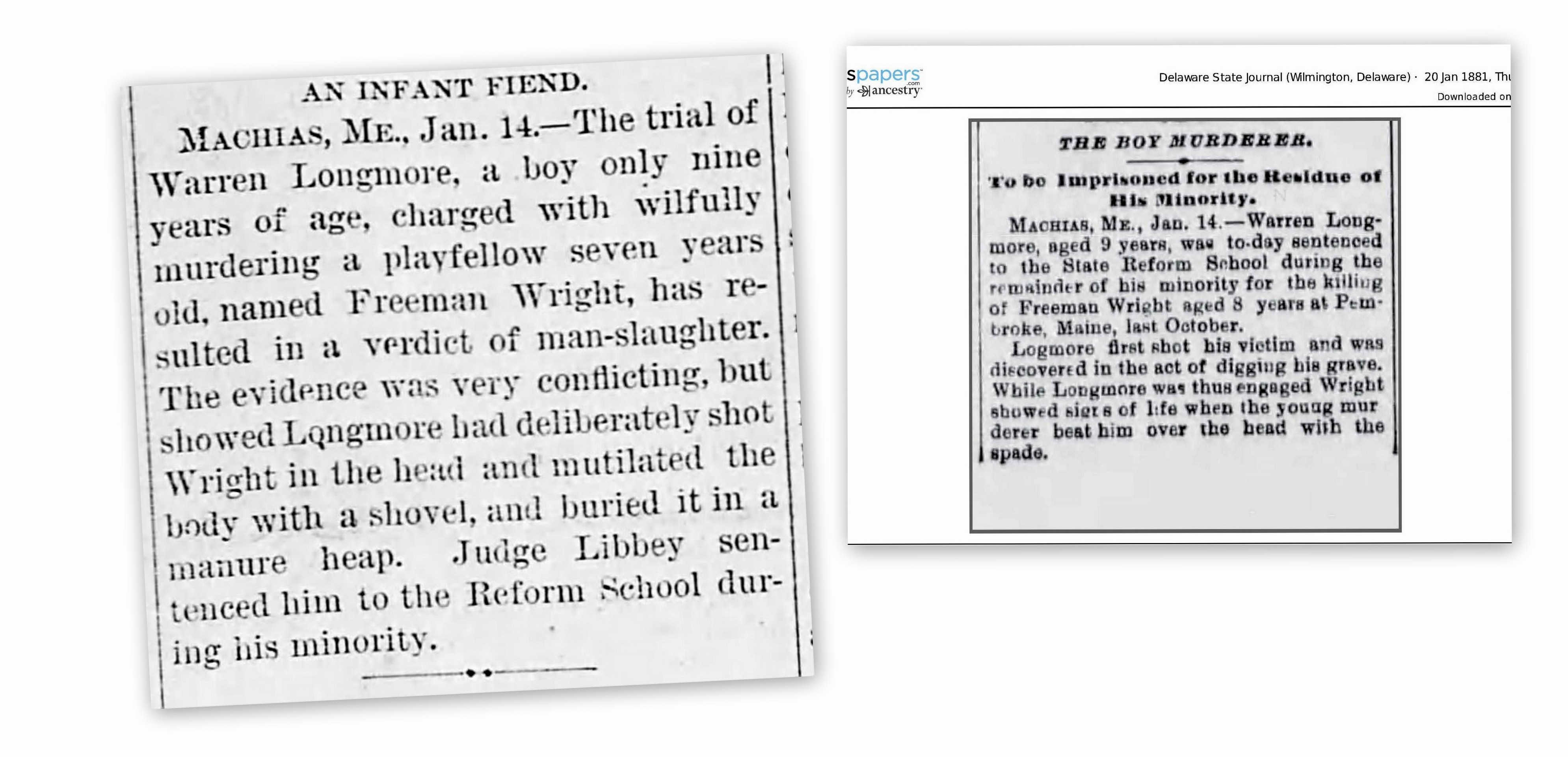

The jury returned in two hours and when asked by the clerk to announce its verdict the foreman answered “guilty” which undoubtedly caused some hearts to stop but the foreman was not finished- he continued “we find the prisoner guilty of manslaughter.” It took the courtroom some time to process what all agreed was a very surprising verdict. The legal establishment was dumbfounded, and the Calais Advertiser mused:

This case was the most extraordinary ever tried in this county, and one of the most remarkable ever tried in any court. And the remarkable feature at the trial was the verdict. How the jury could find a verdict of manslaughter is not explained. It appears to us that the boy was either guilty or innocent of the charge of murder.

The Boston Globe opined:

The jury probably had not the heart to convict of murder, but thought they must punish the boy for something, sensible lawyers think the verdict absurd. Sentence will be imposed tomorrow. The judge is willing to commit the boy to the reform school, if counsel is willing and the law will permit. This ends the first case of a jury convicting so young a child of so great a crime in New England.

Decatur Illinois Daily and Delaware Journal

Sensational headlines were common in the national press after the verdict.

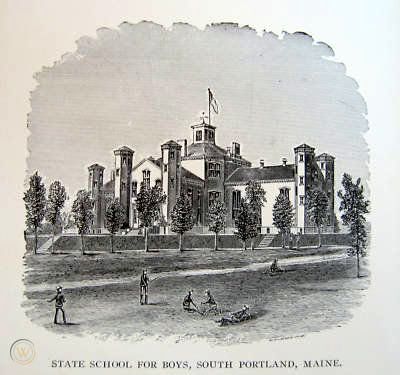

Warren was to spend two years here

The judge did send Warren to the Reform school in South Portland, but he was not destined to stay long. Public pressure was applied on the governor by the local community and no doubt the legal establishment. The public generally agreed with Judge McGraw that the shooting had been an accident and the legal establishment saw the prosecution of a child of nine for murder as contrary to settled legal principles.

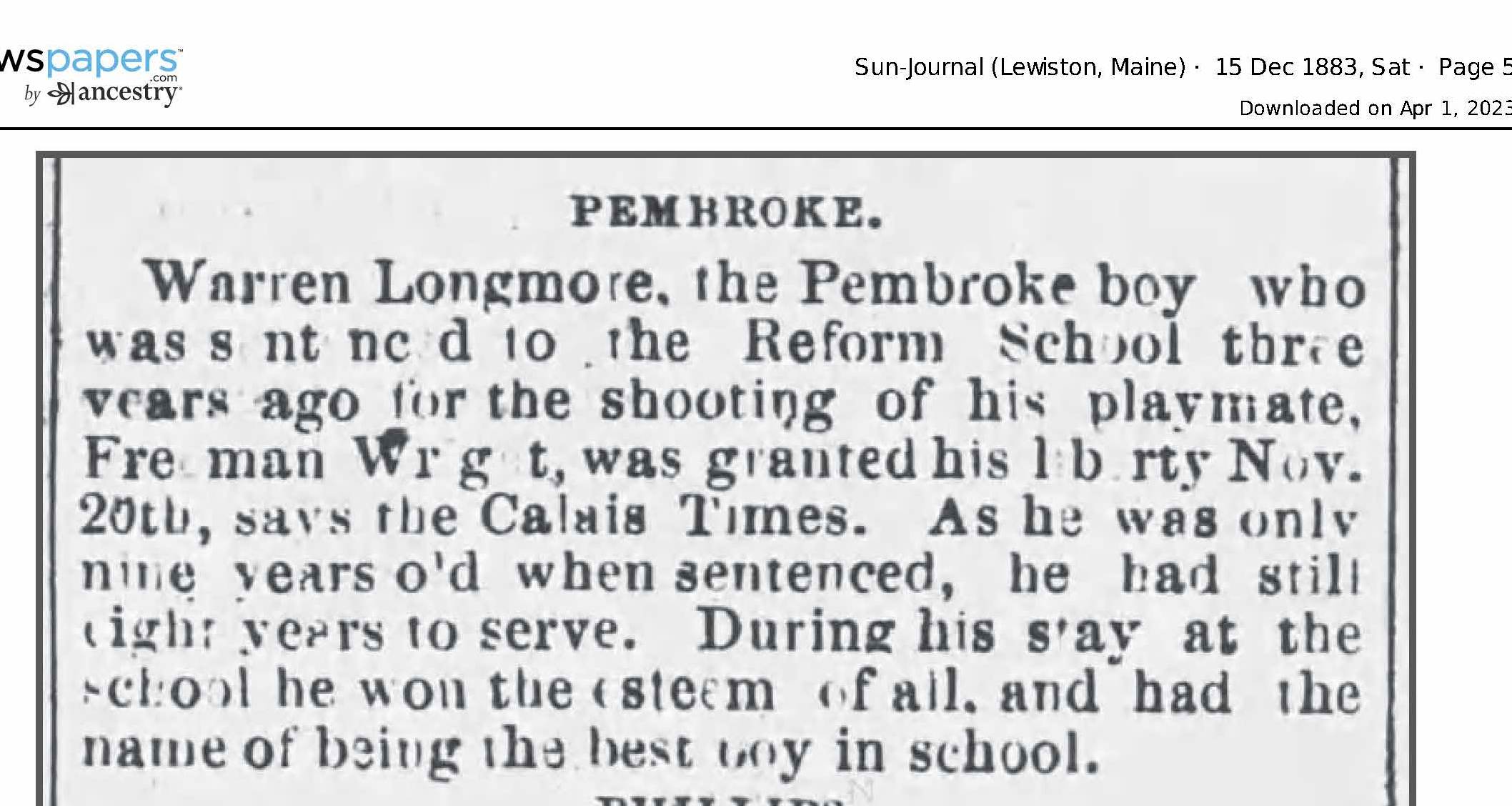

Warren Longmore released 1883

The rest of Warren’s life confirms that he was never the “bad seed” claimed by the prosecution. He moved to Stoneham Massachusetts, married Addie Longman and raised three boys. He was a successful manufacturer of steel and tool dies and was appointed a “special policeman” by the town in 1904. He was a member of the Rotary, Masons, Elks and several other local civic organizations. He died in 1929. He visited Pembroke on occasion probably to see his brother John who remained a prominent citizen of Pembroke.