We noticed in today’s paper [April 3, 2021] that on this day 75 years ago Japanese General Masaharu Homma was executed by firing squad in Manila for his role in the infamous Bataan Death March.

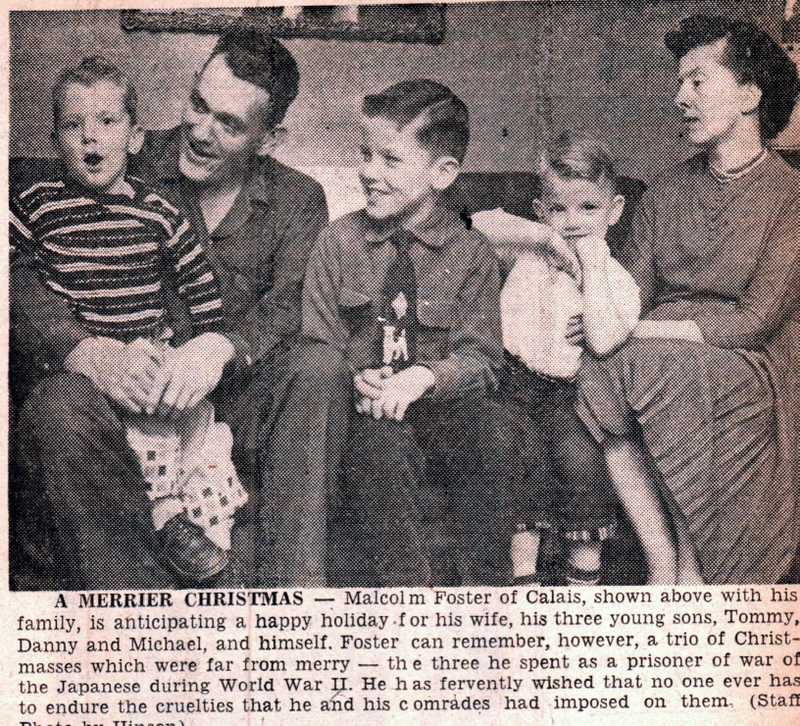

It brought to mind the local connection with this infamous event. Malcolm “Doc” Foster of Calais was an American soldier captured by the Japanese when the Philippines fell to Japanese Forces in April 1942. He barely survived the “Bataan Death March” for which General Masaharu was held responsible and paid with his life 75 years ago today. Doc’s story, told at Christmas 1956 by our own Jay Hinson in the Bangor Daily, is worth reading:

‘Doc’ Foster Still Works For Uncle Sam But His Lot Is Happier Than In 1942

By JAY HINSON CALAIS Dec 24, 1956—Bangor Daily News

On this approaching Christmas Day millions will be joyfully celebrating the birth of the Savior. Unhappily there will also be thousands of people torn from loved ones cut off from their homeland and desperately miserable in their loneliness There have been many other Christmases in the past too when everything was far from merry. Malcolm “Doc” Foster of Calais will never forget the Christmas that he and his buddies “celebrated” while prisoners of war of the Japanese during World War II. The first and worst Yule observance that Foster endured was in 1942 at the Jap POW camp in Cabanatuan about 100 miles from Manila in the Philippine Islands. Briefly the series of incidents that led up to this desolate scene of half-dead Americans sprawled around the prison compound is this as far as Foster himself is concerned: he had enlisted on September 25, 1940 in the Army Air Corps in Bangor, trained at Fort Slocum in New York and shipped overseas on March 31, 1941 for Manila. Assigned to the second observation squadron at Clark Field as a supply clerk Foster was then given training as a parachute rigger and reassigned to Nichols Field just outside Manila.

The Japs struck at Pearl Harbor early in the morning on December 8 Manila time and on December 10 at 1 o’clock in the afternoon destroyed Nichols Field practically wiping out Foster’s outfit. On Christmas in 1941 the remnants of the American fighting forces were moved into Manila and the Air Corps members were given 48 hours training with the rifle and bayonet and formed into an infantry outfit. Foster was reassigned to the Island of Corregidor to salvage parachutes for pilots who were flying messages for General MacArthur. He arrived back on the Bataan Peninsula in time to get his first taste of hand-to-hand combat with Japanese Marines who had tried a sneak attack at Agaloma Bay on February 13, 1942. His unit was at Marvalis Mountain outside Manila when on April 9, 1942 the day of American surrender to the Japanese came. On April 10 22000 Americans and 80000 Filipinos were rounded up by the Japanese and forced to undergo the infamous “Death March” of 82 miles over a winding dirt mountain road from Manila to San Fernando. Foster relates how during the six and a half days and nights of steady marching the prisoners were given only two breaks – one of four hours and the other of two hours.

IN BARE FEET

Foster wore out his socks then his shoes and finally during the last 24 hours of the march walked in his bare feet. Anyone caught accepting gifts of food from natives was killed on the spot and the natives themselves were annihilated. The Americans were taken to Fort O’Donnell in the town of Tarlac where without medication or even a pretense at care they died at the rate of 41 a day. Finally on June 4, 1942 they were transferred to the main prison at Cabanatuan. Weakened by the Death March the men became susceptible “to every disease known to man”. Foster says he himself was attacked by diphtheria and was one of 18 who lived out of the 90 men who contacted this particular disease. Christmas day 1942 was a dark one for the men at Cabanatuan. Foster himself was partially paralyzed by the diphtheria and weighed but 81 pounds, half his normal weight. On this Christmas at the request of the American officers in the prison camp the Japanese issued Red Cross boxes which had arrived in October. Although the Red Cross sent during the war enough of these boxes containing food cigarettes and boxes containing food cigarettes and chocolate bars so that each man could have one a day the prisoners of the Japanese were issued them only once a year. On this day each box had to be shared by two men. These boxes had been sent by the British Red Cross and contained plum pudding, hard tack, a fifth of a pound packet of black tea, half-pound block of cheese, a can of pink salmon, a can of corned beef from Argentina, a block of milk chocolate and a can of sardines. Foster remembers commenting to the fellow he was sharing the box with that he wished he was where those sardines were packed – at Campobello Island 30 miles from his home in Calais.

The filthy ragged unshaven men – none of them had washed in eight months since they were allowed only one canteen of water a day – gathered around in small groups of three and four cooked their ration of rice and added the corned beef from the British Red Cross box. The Japanese gave them cocoa and to this somber celebration was introduced the first hot drink the men had had since they were captured in April. The day was spent in discussing in minute detail the way each had spent his last Christmas at home. Some of the men, many of them obviously not able to last out the week, were making plans for the next Christmas which they were sure would be once again observed in their own homes. Christmas 1943 was spent at Clark Field on Bataan by Foster who was assigned to a work detail building equipment for airplanes.

On this day, the happiest of the three Yules he spent behind barbed wire, the Japanese issued the prisoners an American Red Cross box after calling them in from work at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Foster had rejoined what was left of his outfit and the day took on all the aspects of a reunion. The men once again gathered around in quite small groups and talked about back home. The Japanese did not even allow them to sing, pray or show any emotions and broke up any attempt at holding religious services in the camp Foster was in.

WORKED IN MINE

On August 12, 1944 Foster and 500 others were sent to Japan and in October were put to work in a copper mine in Northern Japan. The Japanese treatment was so heartless and the work so dangerous that 11 months later when the war had ceased 139 of the men had died. Every day of the week the prisoners would arise at 4 o’clock in the morning, eat a meager breakfast, walk five miles to the mine and climb down 285 steps to the work level. With tiny pick axes whose handles were not more than 18 inches long the men working in pairs would load copper ore into railway car capable of holding one ton, push the car themselves a quarter of a mile to dump the contents down a chute and push the car back for another load. Each pair had to load 16 tons of ore each workday which would last until 9 o’clock at night. At the end of each exhausting day the men would climb the 285 steps and walk back five miles to camp where they would eat and fling themselves down on the floor for five hours sleep. On Christmas day in 1944 the Japanese outdid themselves and allowed the men to quit at 4 o’clock in the afternoon – after a 12-hour day in the mine.

The prisoners were issued their third Red Cross boxes from which as usual the Japanese had pilfered the cigarettes and chocolate bars. At no time during the three and a half years Foster was prisoner did he receive any mail. This was true for all the other prisoners that he knew too. At one point he did get a box from home in which were listed 31 items that his family had sent him. By the time he received the precious gift only five small items were left. The Americans got the first inkling at this Christmas that the Japanese plan for world domination was going astray. They allowed a German Catholic priest to say Mass that evening.

These were the three Christmases that Foster and his buddies spent while prisoners. Undoubtedly the happiest day they spent and one which was as wonderful as all the Christmases in their lives put together was on August 25, 1945, a week or so after the Japs had capitulated, and the cease fire order had gone out. The Japanese prison guards had fled and, on this day, big, beautiful B-29’s flew over the prison camp isolated way up in the mountains and dropped food, new clean clothing soap razors and medicine. The stuff had been placed in 50-gallon oil drums and dropped out of the planes’ bomb bays Ironically enough the first heavy container of supplies crashed through the hut of one of the civilian Japanese mine guards and squashed him like a bug. Foster got hold of a gallon can of peaches and downed them by himself. He hasn’t eaten any since. He and the others also put on the first pair of shoes they had worn since June 1943.

After hanging around the camp for a couple of weeks the Americans became understandably restless and a group of them confiscated a train which was used to haul the copper ore to a seaport town 22 miles away. On September 13, the tram load of prisoners chugged right into the arms of a contingent of United States Marines which had been sent to bring them in. The prisoners were expedited all the way back to the states and processed in short order. Foster found himself walking up the path to his home in Calais on Armistice day in 1945 Since then he has married, has three wonderful sons and holds down a job working for Uncle Sam again – in the local post office.

This Main Street building was the St. Croix Club for many years and, now rebuilt, is the bowling club

In a sad twist of fate Doc, who was one of few of his outfit to survive the Death March and captivity by the Japanese, was the only one who did not survive the fire at the bowling club in 1959.