Maine’s semi-official nickname, as we well know, is “The Pine Tree State”, but for many decades Maine had an unofficial and to some degree disparaging nickname: “The Prohibition State”.

In 1846 Maine became the first state in the nation to pass a prohibition law and prohibition, in one form or the other, remained the law in Maine until the repeal of national prohibition in the 1930s. Much of the rest of the country thought prohibition a rather ill-conceived notion and, of course, this attitude was vindicated by the complete failure of the national experiment in the 1920s and 30s.

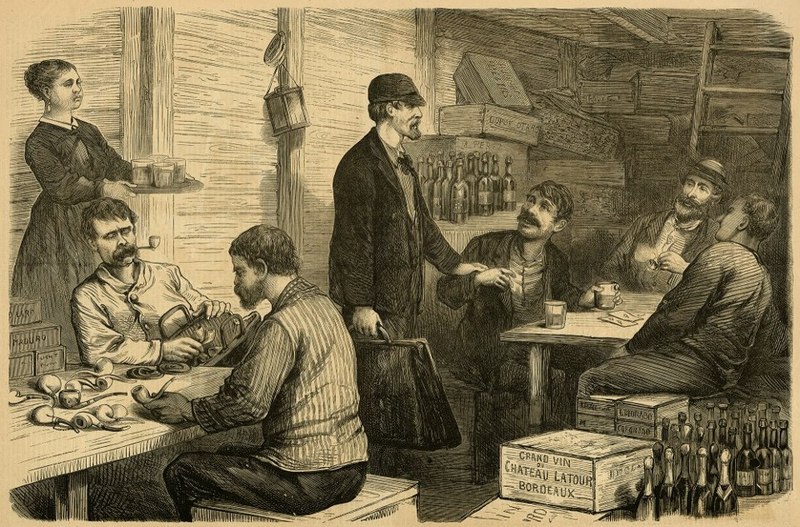

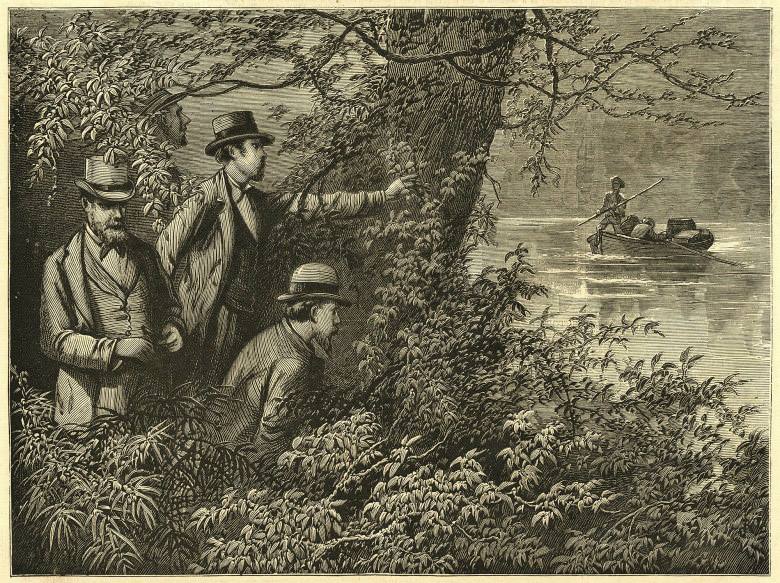

In the 1800s and early 1900s Maine became the brunt of many jokes and was, as we say today trolled, in national publications. Downeast Maine was often cited as an example of the folly of any attempt to criminalize the use and possession of alcohol. The prints above from national magazines of the 1800s purport to show first a “nineteenth century smugglers headquarters in Calais” and the second “SMUGGLING NEAR CALAIS, 1873! A smuggling scene on the Maine / New Brunswick boundary near Calais, Maine.” Earlier in the century even the Superintendent of Trade for New Brunswick, themselves no pikers themselves in the art of smuggling, had described Downeasters as ” lawless rabble”. Harsh perhaps but when describing the local attitude to prohibition, probably accurate.

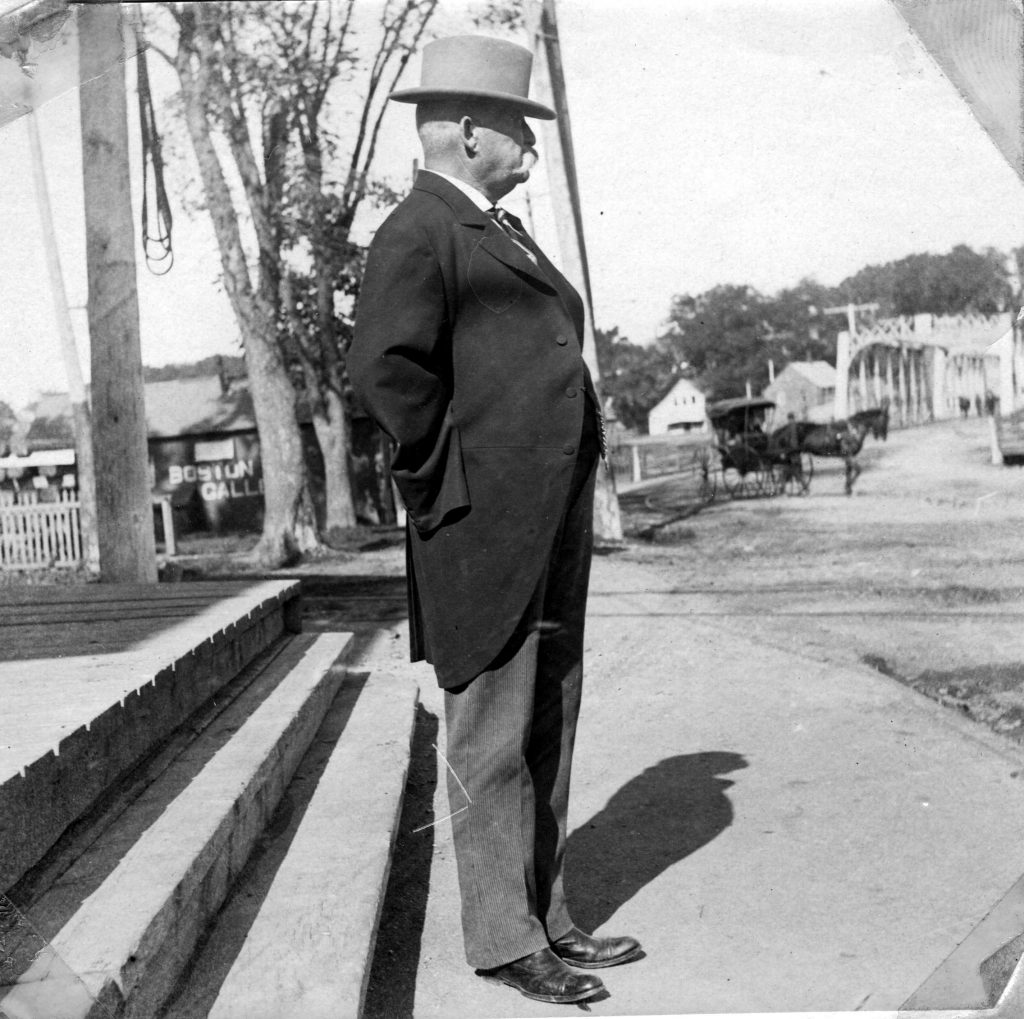

Typical

of the articles published in the national papers of the era was one

published in 1905 describing what may have been the intentions of the

distinguished one-armed gentleman shown above standing in front of the

Andrews Hotel near the bridge to St. Stephen. According to the article

he may well have been planning to take his morning constitutional in St.

Stephen, intending to return with two arms.

Prohibition State

LID IS BOBBING AWAY DOWNEAST

Something About “Drought as it Exists in Washington County.”

The Eastern Maine correspondent of a Boston paper has the following regarding the drought down in Washington county:

CALAIS, Me., May 15, 1905

Happy above all others in this sun-kissed, throat-parched, water-cursed State, are the citizens of Washington county who live along the Sunrise Line across which lies the English land flowing rich with the tender juices of the rye and whose air is fragrant with the uncensured drafts of the distillery. The lid is down in Washington county. But not too hard. In fact, the lid is closed here with a very gentle and susceptible spring permitting it to rise at the touch of a child.

CLOSE AT HAND.

Right across the St. Croix river is the town of St. Stephen in New Brunswick. The first building across the bridge is the custom house, the second a saloon, and the red-dye dispensary has got the government annex lashed to the rigging so far as business is concerned.

At early morn the law-abiding citizen of Calais arises from his couch, and before he has complained to his wife about the coffee is reminded that he has pressing business in St. Stephen. He saunters forth to join that innumerable caravan which moves to the abode of the tinkling glasses and the home of the frajabeous bun.

He may have gone across the dark and rolling river with sadness gnawing at his heart and sorrow clutching at his appendix, but anon, also later, he returns singing joyful tidings, and with a small bunch at his rear pocket where men in a non-prohibitory States are sometimes wont to carry a wicked flask.

By teams, by trolleys and on fool travel the good citizens of Washington county, one grand, united committee on public irrigation.

OTHER WAYS TO GET IT.

But to those who either by distance from the bridge or home duties are unable to take the trip across the river, there are other and scarcely less easy methods of obtaining a glorious, gladsome slant. Washington county teems with peddlers able to deal out the ardent from all sorts of queer receptacles. Of course, there is the ancient book and cane devices, but not so much in favor now because of the notoriety which they have gained.

But with the spread of information new and better contrivances have been made necessary. It was not long ago that a stranger drove into town with a mammoth load of squashes, for which he charged the stupendous prices of 75 cents each. The housewives were astounded at his audacity. With squashes retailing at 2 cents a pound. Every squash had been cut open in a notched circle, all but the shell scooped out, and inside lay a pint flask of a chemical combination which could be drunk for whiskey. The load of squashes was disposed of in short order.

IN HIS HAT.

A clerical looking man, on a walking trip to study the geological formation of the State, made quite a mint of money. He was quite distinguished appearing, never being seen without his silk tie.

As the farmers began to get better acquainted with him, he took off his hat to them, turned a tiny faucet in the tin compartment which filled the upper part and let out the desired fluid. Never in the history of the State has there been so many wooden-legged men traveling about as now. But all the artificial limbs plodding about the country appear to be hollow, and a careful search reveals a small cap, which can be unscrewed to let out the contents.

FIVE-LEGGED CALF.

One versatile man drove a five-legged calf all over the county, ostensibly endeavoring to sell the animal. Not for weeks did the sheriff discover that the reason the calf never was sold was because its fifth leg had been nicely plastered and strapped on, then covered with hair, and was no more than a receptacle for about two quarts of that which made John B. Gough famous.

Bicycles with tires inflated with Kentucky mountain dew instead of air, suitcases with false bottoms, non-leakable dolls, nice for the baby after papa has unscrewed the leg and numerous other ingenious designs for the first aid to the thirsty, still make life a little worth living’ way down here is the “Prohibition State”.

A similar article appeared in the New York Sun in 1884:

New York Sun 1884:

Down on the eastern frontier the towns of Calais in Maine and St Stephen in New Brunswick face one another from opposite sides of the St Croix River. Over the one floats the Stars and Stripes over the other the cross of St George. A big bridge connects the two places and on this structure are transacted many little bits of business in the war of importing which benefit not Uncle Sam nor yet Victoria. A post in the center of the structure defines the spot where Maine leaves off and New Brunswick begins, and a man can stand on the Now Brunswick side of that post with a case of three-star brandy waiting for the American customs officer on the Maine side to go to sleep or got tired out with impunity or a man with some Yankee notion can do the same from the Maine side with Johnny Bull’s collector. Often at night goods are smuggled over and it is almost impossible to prevent it.

When any young fellow kicks up a breeze in Calais, he skips over to the New Brunswick side and the New Brunswick ill doers find a safe haven in Maine. When the thing blows over, they return to their native shores.Election day always brings the Americans back. Whether they have been abroad a month or twenty-four hours their vote pardons them. Years ago, when the prohibitory law was vigorously enforced in Calais the liquor dealers if they got wind of an intended raid would load up their whole stock on a dray and at night over the bridge it would go in a hurry and then when the red tape Mother Hubbards went to the cupboard they found it bare and so the poor law got none.

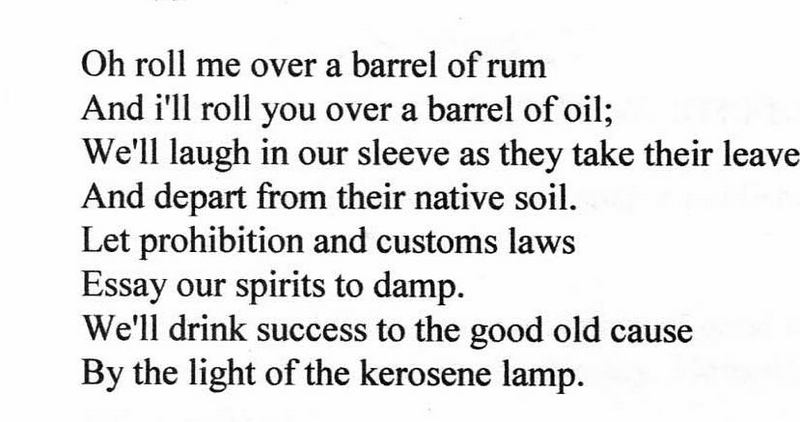

Even the local poets found the idea of Prohibition amusing.

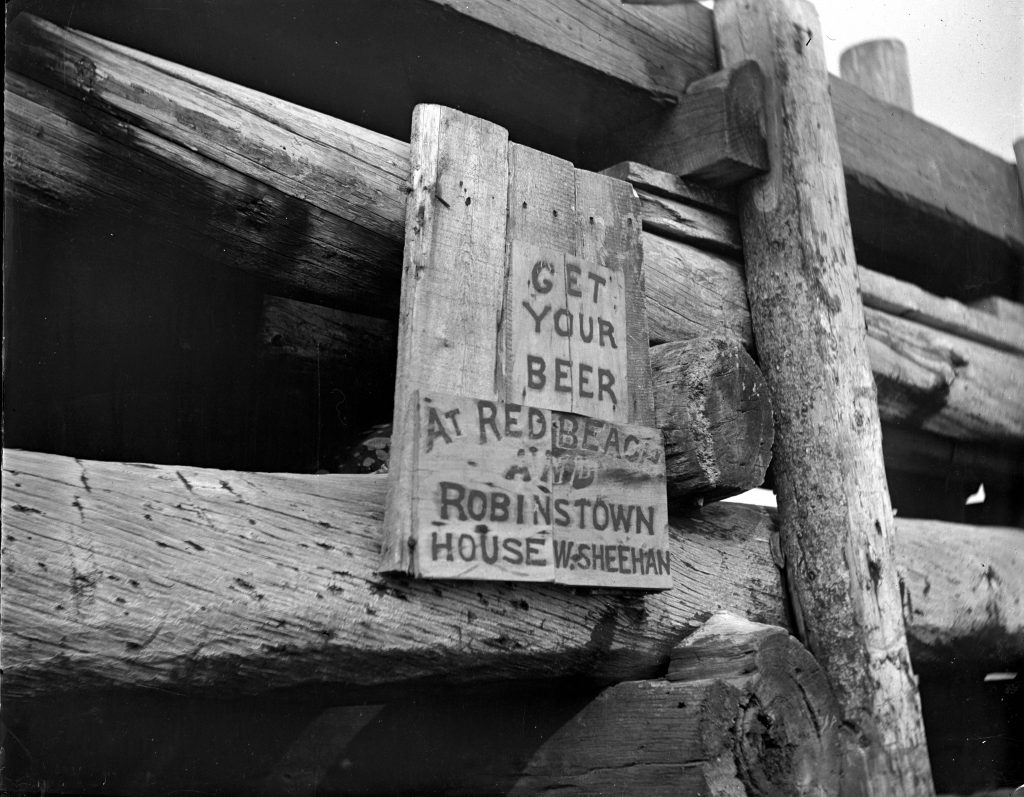

The sign above was nailed to a pier on the Calais waterfront and we truthfully don’t know if it was an advertisement for the illicit offerings at O’Brien’s Robbinston House or an attempt to embarrass the proprietor and Mr. Sheehan who it seems operated a similar establishment in Red Beach.

We are very fortunate to have a first hand account of rum running in the 1920’s and 30’s from Louis “Louie” Morrison pictured above in his graduation photo from Calais Academy in 1940. The other photo above shows “Rum Row” the collection of bars which stretched from the corner of Union Street toward the bridge after the repeal of Prohibition in the 1930s.

Prior to repeal these businesses had mainly been small restaurants that served very little food but had a steady clientele during Prohibition. The “Union” was for about 100 years the center of smuggling, bootlegging and illegal speakeasies in Calais. The following is a rough transcription of a conversation we had with Louie at his home in the Union in 2009. Louis was born in 1921 and grew up on Price Street in the Union. He recalls Prohibition very well as the Union was where all the smugglers lived including many in his family. According to Louie:

Vessels usually from Belgium would lay about three miles off shore. The rum was in three gallon steel or tin containers called “Hand Brand” because it had a print of a man on the side. Fred Spinney who owned a store at the corner of Main and Union and lived in the Union would get word the boat had arrived and he would take his speed boat which he kept in St. Stephen out to the Belgian boat, pay cash and load up with cans of 180 proof Hand Brand. These he took back to St. Stephen to a place near the axe factory on Dennis Stream. My uncle John would take his horse drawn wagon across the bridge and put a half dozen or so cans of Hand Brand in the cart and then go to Haley’s lumber and have them with covered scraps ends of apple boxes or other scrap wood and go back across the bridge to Calais. I often accompanied him on these trips. The Customs Officers knew what was going on but never searched the cart.

Uncle John also lived in the Union and had 10 kids and supported the family entirely by bootlegging. He also owned a small lot near the St Stephen cemetery and would sometimes meet his Canadian seller there where he would cover the cans with loam before returning to Calais.

Another Uncle, Ed Curran, worked for bootlegger who supplied Ed with a huge Valley Touring car to run rum to Boston Market.

An older boy who lived in the Union named Harold Porter was a very strong swimmer and had a regular job smuggling Hand Brand by swimming across the river when the tide was right below the Union Street bridge at a place called Indian Rocks and bring back a can tied to a rope around his neck. When he swam back to St Stephen there would be a couple of dollars and another can. He kept swimming until he returned to find only the money. Harold never knew who he worked for.

Louis recalls an incident in which the Feds confiscated a large quantity of bootleg alcohol and loaded it into a locked railcar in back of Louis place on Price Street. When they returned the next day the railcar was empty.

His Uncle John always had a ready supply at his house. His customers would leave with a bottle of “split” which is 180 proof alcohol mixed with water and sugar in a baby bottle. His uncle was only one of many homes on Union Street in the bootlegging business.

Louie also said that the City Marshall, Bobby Kerr, was a Union boy who protected the bootleggers. Bobby’s brother Herbie never had a job other than bootlegging. Always wore a large overcoat with spacious pockets.

Louis Morrison remembers Bobby well. Louie says:

The Kerr family grew up in a house which still stands at the intersection of Pleasant and Union Streets. Almost all the bootleggers in those days lived in the Union. Louis remembers Bobby as tough but fair and says he was especially fair when it came to bootleggers. Enforcement of prohibition was not high on list of Bobby’s priorities, first because he was a Union boy himself and, second because most of the citizens of Calais were, shall we say, a bit ambivalent about this particular law. The Calais Advertiser, which was a strong supporter of Prohibition, often editorialized that civic leaders, men who were usually the husbands of the women in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, were either the biggest bootleggers or biggest customers of the bootleggers in the City. According to Louie, pressure from the WCTU would occasionally result in a call from the Governor to the Sheriff of Washington County demanding some action be taken against the bootleggers. As soon as Bobby got wind of the impending raid, the gin joints and speakeasies on Rum Row would suddenly go dry and would stay dry until the Sheriff had left town empty handed and the bootleggers got word the heat was off.

As noted above the Temperance movement was not without local support. A Temperance society was formed in Calais as early as 1828 although it was short-lived. An article by Ed Boyd, a noted local historian, says another temperance society was formed in Goodnows Hall (St. Croix Opera House block) July 14, 1841. 42 members pledged themselves to total abstinence except on the fourth of July, Washington’s birthday, and their own birthday. It is said the rules were loosened to allow drinking on other members birthdays and the experiment failed.

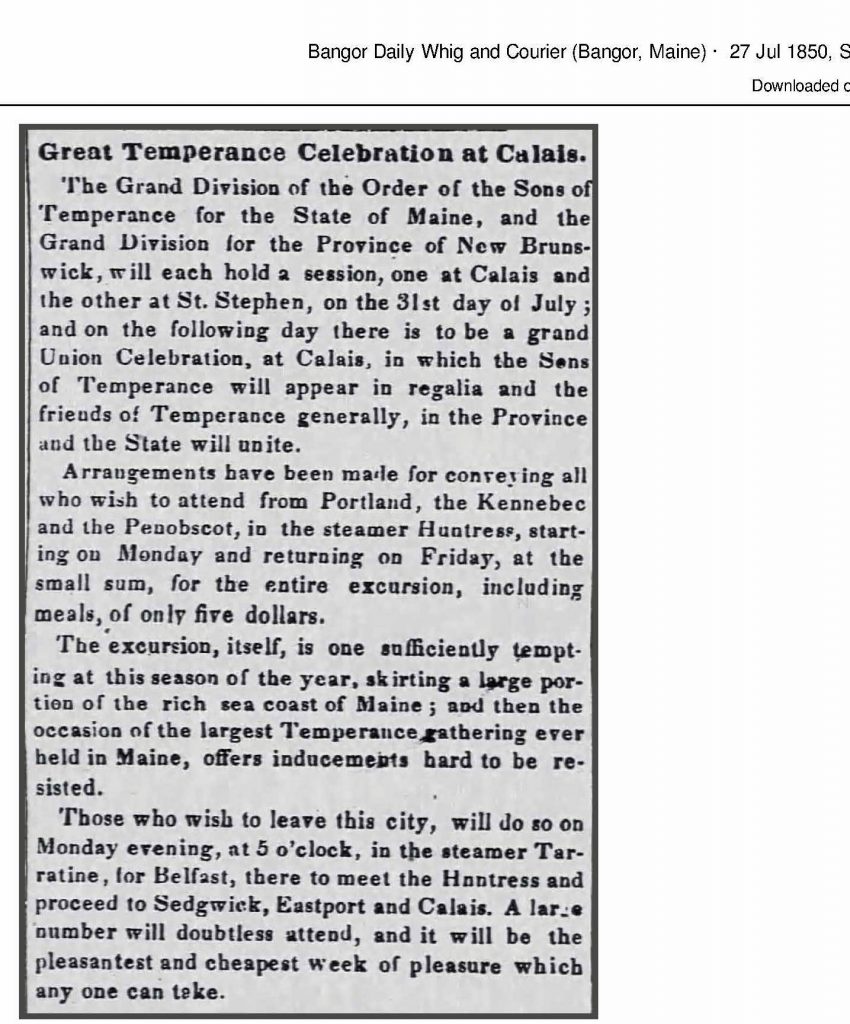

Still

the movement remained active as shown by the 1850 “Temperance

Celebration” advertised in the Bangor Whig and Courier and an article in

a Lewisburg Pennsylvania newspaper in 1882 describes a “Temperate Jubilee” held in Milltown N.B. and Calais for the 4th of July in 1882. While the national press was describing the lawlessness associated with Maine’s prohibition law, this correspondent thought the law to be working wonderfully.

Correspondence of the Chronicle of Lewisburg Pennsylvania 1882

A Temperate Jubilee. Milltown, N. B., Canada.

On the opposite side of the St. Croix lies the city of Calais, Maine. With a population of about 7,000, and with the adjacent towns of St. Stephen and Milltown, N.B., the number of people gathering upon any occasion would reach fully 10,000. Yesterday the 4th was celebrated with the unusual patriotism. A long programme of sports and games had been prepared, and bulletins sent far and wide. The gathering began early in the morning, and the stream of people coming in from the surrounding country was strongly suggestive of the great political gatherings held in Lewisburg during the excitement of the political meetings immediately after the war.

Now, as a simple incident, when reliable and capable of being used as an illustration, will have more force than tomes of argument, de assertions, I thought I would call your attention to one of the features of the celebration. It confirmed the hopes of those who look for a Prohibitory Law in the other States. The Maine Law I have found to be so often misrepresented in Pennsylvania that this one incident will not be inopportune. The Law is said to be a failure. It is not enforced, they tell us, and it is almost a burden upon the citizens of that State. A few fanatics support it, but public sentiment is so adverse that practically it amounts to little more than form. But yesterday convinced me of its beneficial results. I was a witness of many of the crowds, walking among them, and surveying them at a distance. The games were such as would call out a disorderly element. The saloons in any other state would have been crowded. Much drinking and much quarreling would have been seen from morning to evening. But in this gathering of a full 10, 000 or 12,000 people at a low estimate, with many strangers from St. John, N.B., and other cities, I remember of seeing but one drunken man and neither heard of nor saw a quarrel. The man who was intoxicated was on the English side of the river. This morning I find, upon conversing with several others, who were in the crowd a greater portion of the day, that they saw not more than 3 or 4 who were intoxicated, and neither saw nor heard of a quarrel. And these people of Calais explain the ” drunkenness” by referring us to the fact that liquor is sold on the Canadian side of the river. ” But” they add, ” the Province itself will soon have its Prohibitory law in action, as a case upon which much rests will be decided very shortly in their Supreme Court. They delay until this is set at rest. At one time Milltown had the prohibitory law enforced. But it has been contested before the highest courts and the privy council. A decision before the last was reached about a fortnight ago, and it will become active again as soon as this subordinate point is decided in the provincial court. When the law was enforced a drunken man was a curiosity to many. All have feelings of repugnance to drinking, both here and on the other side, that almost astonishes a native of a state which is not oppressed by that form and fantasy of forms, the Maine law. “What if they were transported to that fair town of Sunbury or Shamokin on a great gala day! The latter used to have 92 saloons open, and a quarrel, perhaps a murder, was a common occurrence, gala day, or Sunday. Human nature is the same the world over. Surroundings are different, and the men consequently differ. Why not make the surroundings of the good citizens of Penn., equal to those of these Down Easters?

– G. A. Mark.

G.A. Mark’s rose colored view of Downeast and his appeal “make the surroundings of the good citizens of Pennsylvania equal to those of Downeasters” was ill informed at best. The battle between the economic forces which sustained the liquor trade and moral certainties of the temperance movement was probably more intense here than in most other parts of the country where the temptation and supply was not just a stone’s throw across a very narrow river.

For decades the Calais Advertiser carried weekly reports of arrests for intoxication, brawling, the closing of “disorderly houses” and appeals to shut down bars and restaurants. Calais’s finest hotel, the St. Croix, was raided on a regular basis. Even after the repeal of Prohibition in the 1930s the battle locally continued for decades with many restrictions on alcohol sale in Calais and surrounding communities lasting until after the Second World War and beyond.