A pack of grey wolves

I’ve written extensively about the Airline and the Airline stagecoach over the years. It is a truly romantic tale of brave men and strong horses who together conquered the wilderness between Calais and Bangor over what was known as the “Wolf Route.” However, it was not without its price. Breakneck Hill just west of Wesley is so named because in 1869 George McCurdy, one of the best and most popular stagecoach drivers on the Airline route died of a broken neck on the hill. Is it possible a pack of wolves were responsible for McCurdy’s death?

The legendary Wilber Day who lived just a few miles from Breakneck Hill describes his death:

“I remember very well some of the (stage) drivers, more especially poor George McCurdy who was killed on the road one night between our place (Sam Day place) and Mr. Bacon’s, with Mr. McCurdy hanging head down, caught by a foot in the iron fender or rail on the front of the coach. Mr. McCurdy was a kind hearted man and fond of children and was much missed by all.”

According to Laurie (Bent) Forbes, daughter of Everett Bent, who was the son of Helen Marie Mingo of Red Beach:

George Frederick McCurdy (1842-1869) was the father of George Frederick, Jr. and of Minnie Mae McCurdy, who married Walter Mingo, lived in Red Beach and had three little girls: my grandmother Helen Marie (Everett’s mother, called “Marie”), and then Janie Caralen and Vera Grace. Minnie (1869-1900) died at age 31 of tuberculosis, when my grandmother was 10 years old. Minnie’s older brother, George Frederick McCurdy, Jr. (1864-1935), whom my grandmother Marie called “Uncle Fred,” didn’t marry until 1908. He lived with his mother, Lydia Maria (Seaman) McCurdy (1837- 1906), who was a dressmaker and never remarried after George Sr. died in 1869, two days after Minnie was born. George Sr. was a teamster and stagecoach driver and was killed in a road accident on Route 9, beyond the Machias River toward Calais: mile marker 253, or thereabouts.

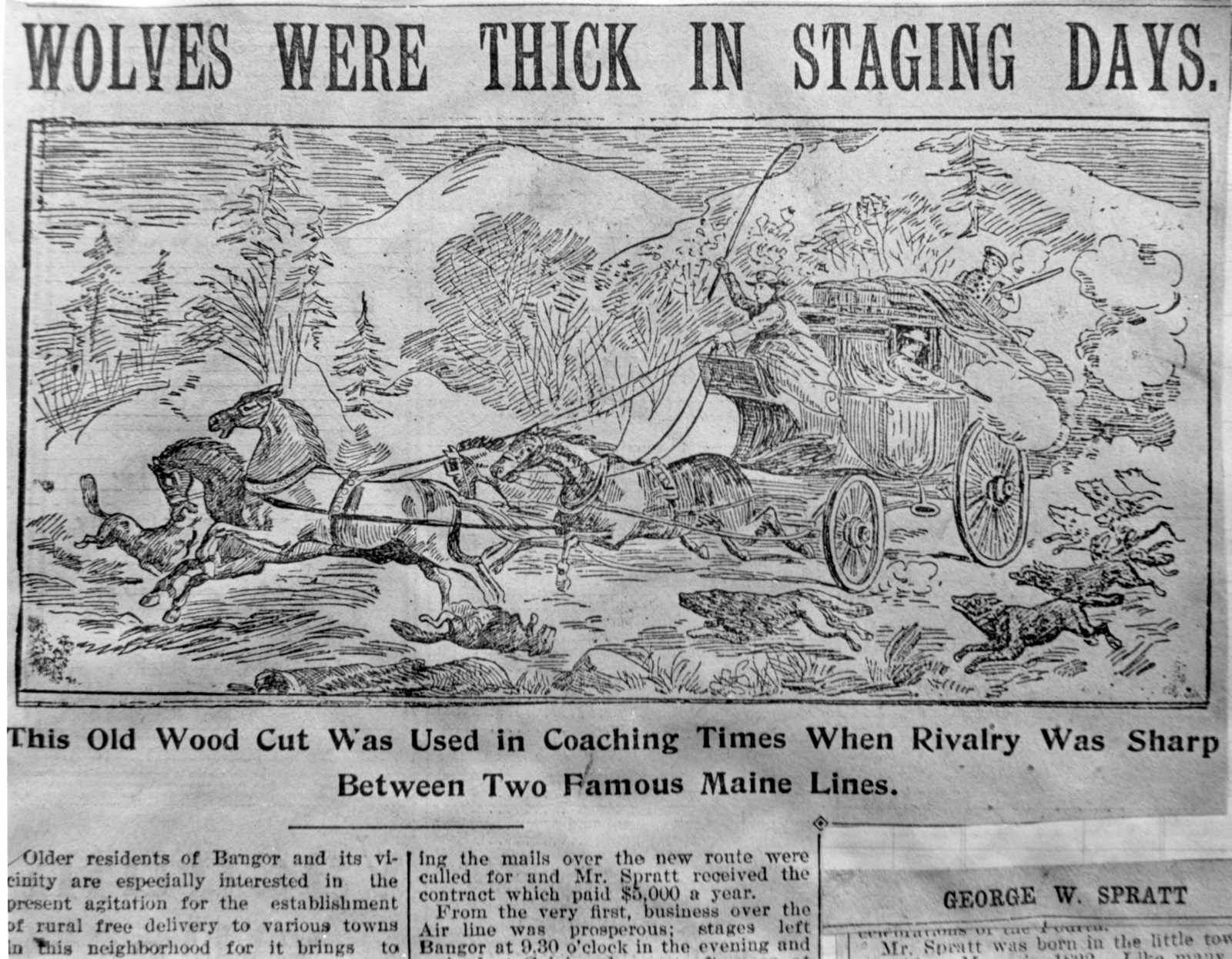

Terrified horses bolt from attacking wolves on the Airline, circa 1860

John Dudley writes that the account assumes that George McCurdy fell when applying the brake lever as the stage, perhaps traveling too fast on the steep downgrade, went down the west side of Breakneck Hill. Those with more imagination and less knowledge of the difficulty of handling a team of horses on a steep downhill grade would have suspected wolves of spooking the team.

Some accounts say he was still alive when the team arrived at the Bacon farm but survived for only a few minutes. There is no reason to believe McCurdy’s team was attacked or spooked by wolves on the hill, but the Airline Stage line’s competitors would certainly have suggested wolves were responsible. As we have explained in past accounts the image shown above was produced by the Airline Stage Company’s fierce competitor the Shore Road Stage Line in an attempt to discourage passengers on the new line. It failed in spectacular fashion because adventurers flocked to the Airline Stage just to get a shot at a wolf. In human imagination wolves are devious, sinister and cunning killers and sneaky, ruthless predators. The damned are thrown to the wolves, debtors have the wolf at their door and humans morph into cannibalistic werewolves. Little wonder humans throughout history have been determined to eliminate them without mercy.

There were still many wolves in the forests between Calais and Bangor in the 1850s and 60s when the Airline Stage began operating but they were much diminished in numbers from the late 1700s and early 1800s when wolves ruled the forests of Washington County and exacted a heavy toll on struggling pioneers. In 1791 the residents of Calais filed a petition to abate their taxes because of the depredations of wolves on the town’s sheep and cattle:

Petition filed with the Court of Common Pleas in Machias dated March 17, 1791, by the residents of Calais when it was still Plantation 5. In the petition the residents strongly protested the outrageous amount of the “county tax” which was then being demanded of Calais to fund the operation of the county government. The petition pointed out that Plantation 4 (Robbinston) with a population of 55 to Calais’ 59 and having “more property and better privileges” paid less than half the tax of Calais. The strongest argument for the abatement, however, was wolves: “The wolves has destroyed dubble the number of sheep and cattle (or near it) in this Plantation to any other Plantation in the County, therefore, we find ourselves very unable to pay our taxes was they in proportion but are much more unable to pay a double proportion.”

Wolves also ravished the deer population on which many depended for food during the winter. In 1830 George Boardman of Calais reported “there were no deer to be had in the area because the wolves had killed them all.” This led in 1832 to a substantial bounty on wolves and they gradually disappeared from Maine forests. There have been no wolves in Maine since the 1890s.

As noted above, however during the early 1800s wolves were a constant threat to the livestock of settlers and the game upon which the settlers depended for food. An account from the 1830s of a writer visiting a lumber camp confirmed the problem:

I remained at the camps a week. The lumber was large pine, and the best cut was made into square, timber for the English market. No small pine, spruce or hemlock was cut. One man was employed to look up the timber and to hunt moose to feed the men. There were no deer in the woods; none had been seen for several years. It is said the wolves had destroyed them.”

A woodsman described encounters with wolves in the 1840s while hauling lumber from the woods with a team of oxen:

Some of the teamsters were much alarmed, keeping close to the oxen, and driving as fast as possible. Others, more courageous, would run toward and strike them with their goadsticks; but the wolves sprang out of the way in an instant. But, although they seemed to act without motive, there was something cool and impudent in their conduct that it was trying to the nerves-even more so than an active encounter. For some time after this firearms were a constant part of the teamster’s equipment.”

While moose and caribou were generally not attacked by wolves, a deer attacked by wolves stood no chance:

From Forest Life 1840s:

“My attention was suddenly attracted by a distant howling and screaming-a noise which might remind one of the screeching of forty pair of old cart-wheels (to use the figure of an old hunter in describing the distant howling of a pack of wolves). Presently there came dashing from the forest upon the ice, a short distance from me, a timid deer, pursued by a hungry pack of infuriated wolves. I stood and observed then. The order of pursuit was in single file, until they came quite near their prey, when they suddenly branched off to the right and left, forming two lines; the foremost gradually closing in on the poor deer, until he was completely surrounded, when, springing upon their victim, they instantly bore him to the ice, and in an incredibly short space of time devoured him, leaving the bones only; after which they galloped into the forest and disappeared.

The Hicks family of Meddybemps records in a family history that the matriarch of the family recalls living in a log cabin about 1840 and at night the lights of their humble abode attracted wolves who brazenly looked into the windows at the occupants. Many accounts claim their howling and “screaming” at night was terrifying. A Baileyville history recounts the situation of frontier women in those early years:

A frontier woman not only had to attend to her usual housekeeping duties under difficult conditions, but also had to possess the strength and ability to handle many of her husband’s chores. He was often away in the woods all day—sometimes for weeks. This meant that she must keep the hearth fired up for warmth and that took cords of wood, much of which she chopped herself. Water had to be drawn in the below zero weather from the well and there were paths to shovel through the deep drifts of snow, that at times almost isolated the cabin.

She must know how to handle the musket to keep prowling brown bears and the wolves away. Stored corn in the underground barn must be dug up for food-there were many hungry children to feed. In between times, there was mending, knitting, weaving and the sewing of new clothes to do. Often, she had to climb up and caulk leaking openings in the snowy roof.

Even the mailman had to worry about wolves. In 1811 the Lubec mail came once a week from Machias through the woods. The “carriers went fully armed for protection against wolves and bears which were plentiful.”

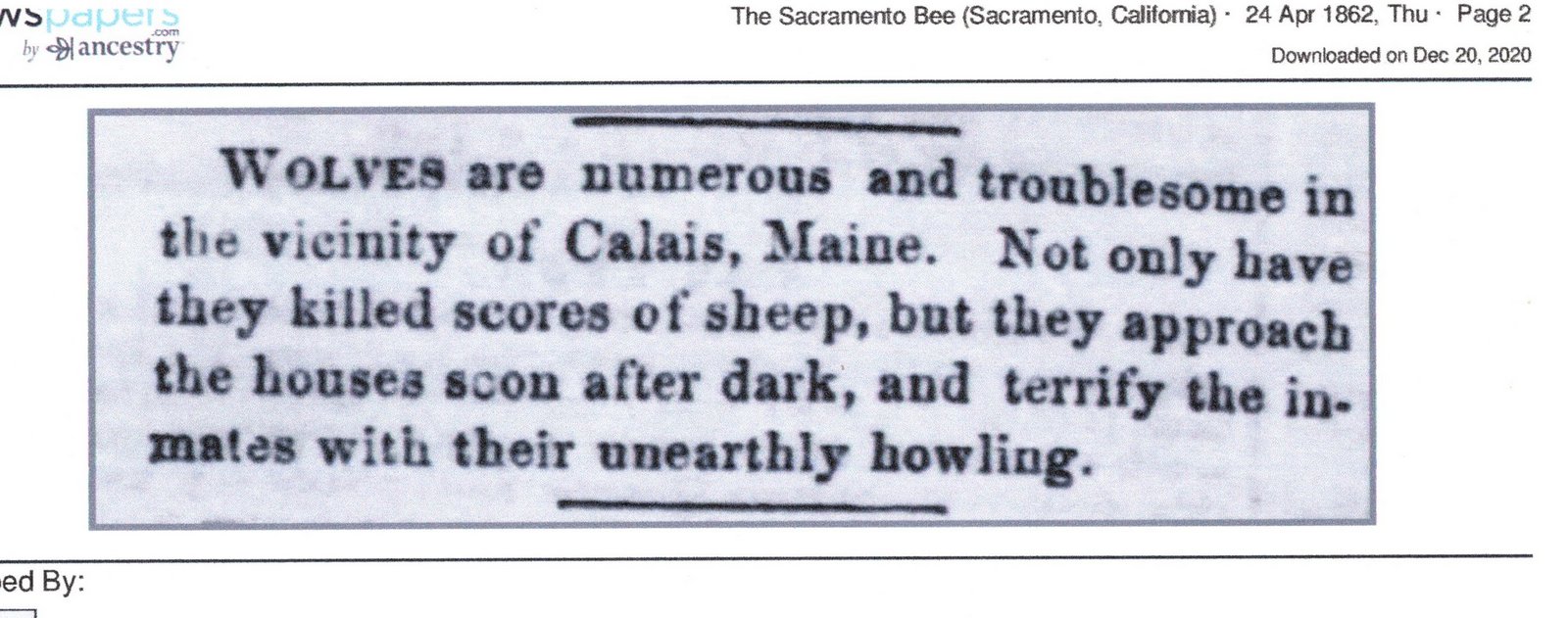

Even though the bounty enacted in 1830 was gradually exterminating the wolves they plagued Calais in 1862 and it was generally known that the two score miles of the new “airline” route between Beddington and Wesley was troubled with wolves.

Boston Globe December 3, 1892, described a journey over the Airline in the 1860s:

The animals were heard nearly every trip chasing deer around the ponds which are so thickly sprinkled through the region, while their howling at night alarmed the drowsy and timid passengers and frequently sent the horses into a mad run, when all the skill, strength and courage of the driver were required to check them.

In 1893 the Lewiston-Sun Journal reported as incident which occurred in the 1860s concerning Mr. Swan, a native of Calais:

In reading the sad accounts of hunger-maddened wolves attacking human beings in Bosnia few people recall that within forty years these merciless beasts of prey were quite numerous in this State. One of Portland’s prominent bankers Mr. Swan of the firm of Swan and Barrett whose former home was in Calais many years ago passed over the old “air-line” or military road which ran directly through the vast forest that still stretches from near Bangor to the Calais line. The road was a direct line over mountain, plain, and valley that was the shortest cut between two given points, and the primeval forest covers nearly the entire distance. Mr. Swan was a passenger on one of the old sleigh coaches and trying, with his companions, to keep warm when his attention was called by the driver to the fact that they were being pursued by wolves, fortunately not a large pack. They kept close to the sleigh which was being drawn at their utmost speed by the flying horses but only approached within a certain distance and after a long pursuit on the edge of a small hamlet they gave it up.

It is agreed that wolves generally avoided direct human contact and there is no reported instance of wolves attacking a human but it is said their cries in the forest on a dark night could be terrifying. One account from the mid 1800s claimed, “Wolves were plentiful and made music every night.” Israel Andrews, the founder of Andrews Store and Hotel near the Calais bridge is said by the Lewiston Sun in 1911 to have been Washington County’s greatest wolf hunter.

The wolves infested the woods near Cooper for a few years eating the sheep and dogs and disappeared just as suddenly as they appeared. It is an accepted fact that to Mr. Andrews belongs the credit of killing the most wolves in Washington County. Mr. Andrews states that the sight of a wolf is not more fearful than of a ‘meechin dog” They are lean and slouchy looking, but he says that their cries in the forest on a dark night are terrifying indeed.

In 1903 there was a rather lurid and clearly fictitious account of an attack by a wolf on a Mr. Armstrong near St. Andrews who had spent the night in St Andrews consuming Christmas cheer. It was no doubt a parody and statement in support of the Scott Act, a largely ineffective law passed by the Provincial Legislature to discourage the consumption of alcoholic beverages in the province.

Fought with Wolves

Desperate Encounter near St. Andrews 1903

“DON’T TELL ME that there are no wolves in Charlotte County;’ remarked a well-known resident of the rural districts to the Beacon a few days ago. “I had an experience with them going from St. Andrews not long since that I will not forget in a hurry. I had been in town buying holiday supplies and enjoying myself and had postponed my departure until well on in the night.

I had not gone far on my journey when I began to see wolfish shapes all about me. They made no noise but crept stealthily after me, stopping when I stopped and quickening their pace when I tried to escape from them.

Try as I would I seemed unable to get out of their sight. My actions emboldened them, and at last one, bigger, bolder and uglier than his fellows, leaped upon me and bore me down. In a twinkling I was surrounded by snapping, snarling fiends. To my frightened vision they assumed all sorts of monstrous shapes. The one that held me by the throat was a terrible monster. His fangs dripped with bloody froth as he tore at me. His breath fairly overpowered me, while his blood-shot cruel eyes threw baleful glances at me that caused my frightened tongue to cleave to the roof of my mouth. I tried to scream for help, but my feeble cries were drowned by the weight of the brutes that held me down. They trampled over me, ripped my clothing in tatters, dragged at my ears and bit me in a score of places. I felt that my last hour had come. I thought of my wife and children waiting expectantly for me and my promised Christmas gifts at home. I wondered how they would get along without me. I even wondered what my friends would say when they found my mangled body and what tune the band would play as they planted the fragments. All of sins of my life, and they seemed to be legion, came trooping up before me. The thoughts of my family gave me fresh strength and hope and I fought as I had never fought before to escape from the clutches of the blood-thirsty pack. My struggles were successful, and I had the satisfaction of seeing my foes retreating one by one into the forest.

When I awoke my sled was lying across my body and the empty flask of Scott Act whiskey, which I held by the neck in a delicate grip, bore mute yet eloquent testimony to the desperate struggle I had made to overcome it.

Don’t tell me, please, that there are no wolves in Charlotte County because I know better’.’-St Andrews Beacon, January 4, 1906

The Beacon had recently reported on several alleged encounters with wolves in the outlying areas, the last on the testimony of a man who claimed to have been pursued by one almost to his door. Armstrong puts his own sardonic spin on the subject. Provincial wildlife officials say the last time a wolf was reported killed in the province was in 1876 but the St. Croix Courier in 1894 reported that “wolves have been said to have made their appearance on the Maine border with this Province and a year later wrote:

The people of Little Ridge are convinced that the much-dreaded wolves have appeared in that locality. A number of deer recently sought shelter in a door yard there and were so terrified that it was difficult to drive them away. Tracks were found in adjoining woods which were declared by Mr. Patrick Haggerty, an aged and respected resident, to have been made by wolves.

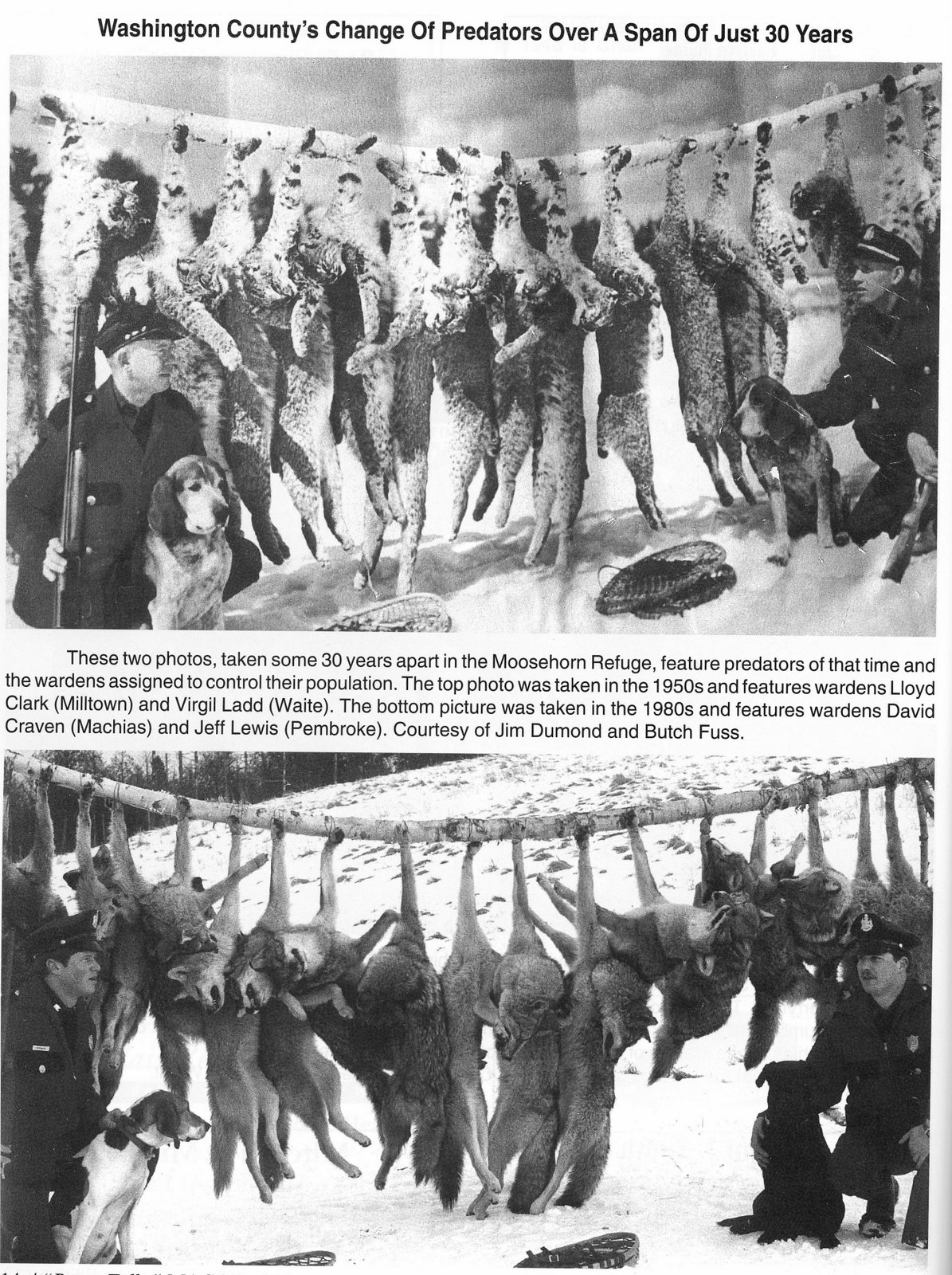

Change in predators at the Moosehorn

Wolves disappeared in Maine by about 1890. Occasionally someone will claim to have seen a wolf, but it is not a pure grey wolf, at least according to the Wolf Conservation Center. According to experts at the Center, the Western Great Lakes Region has a grey wolf population of about 4500, the largest in the continental United States. Alaska’s population is 7000 to 11000 while there are scattered smaller populations in the Rockies and Pacific Northwest. There are none in New England although many resemble the grey wolf as seen in the photo above from the Moosehorn Wildlife Refuge.

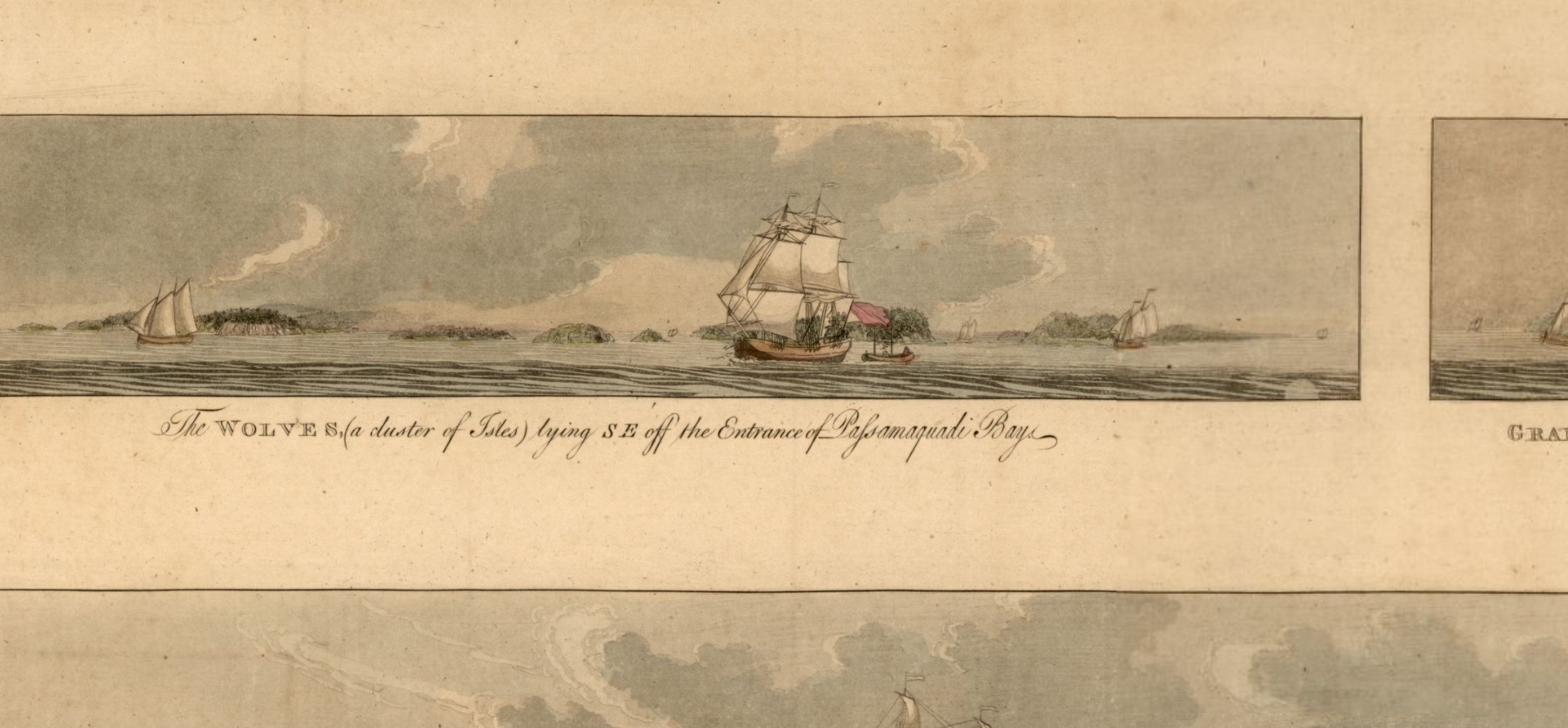

The Wolves in Passamaquoddy Bay, painting 1800’s

Lighthouse on the largest of the Wolves Passamaquoddy Bay

In doing the research for this article I came across many references to the “The Wolves,” a group of small islands at the entrance to Head Harbor Passage. The barren rocks seemed an unlikely place for a pack of wolves so I was curious to determine how the islands got their name. One only has to glance at a map of Passamaquoddy Bay to see that the answer is perfectly logical.

INDIAN LEGENDS

How MOOSE ISLAND, DEER ISLAND AND THE WOLVES WERE NAMED

One day, so the legend goes, an ornate canoe came from over the seas and landed on these shores; in the canoe was a great chief named Glooscap. The people all followed Glooscap for they soon learned that he was very wise and good and had great magic powers. He could turn his enemies into a piece of wood or a lump of clay with the wave of his hand — and the sun, wind and rain did his bidding.

As Glooscap was paddling his canoe along the shores of Passamaquoddy Bay one morning, he heard a commotion nearby and saw a pack of wolves chasing a deer and a moose out of the forest and into the water. Glooscap watched until he saw the pursued animals tiring, with the bloodthirsty wolves preparing to make the kill. Then he lifted his hand, changed them all into islands. Today, Deer Island and Moose Island, on which the city of Eastport is located, are still side by side in Passamaquoddy Bay with the Wolves still in pursuit a few miles offshore.