“Go west, young man, and grow up with the country.” – Horace Greeley

Cyrus Hamlin, Calais’s second doctor and brother of Lincoln’s Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin, would not have been familiar with Horace Greeley or his injunction to settle the American frontier. He had done so a decade before Greeley’s famous 1850s advice, and did not long survive his westward journey. Still, his story is an interesting one, and says a good deal about the spirit of adventure which animated many of the early settlers of the St. Croix Valley.

In 1830, Cyrus Hamlin arrived in Calais at the age of 28 and took up residence in the Holmes Cottage on Main Street. The cottage stills stands today as one of the oldest buildings in Calais and it has changed little over the last 200 years. S.S. Whipple, the first doctor in Calais, had practiced medicine from the cottage for about a decade before selling the practice and cottage to Cyrus about 1830. The Fine Artists in their history of the cottage say of Cyrus

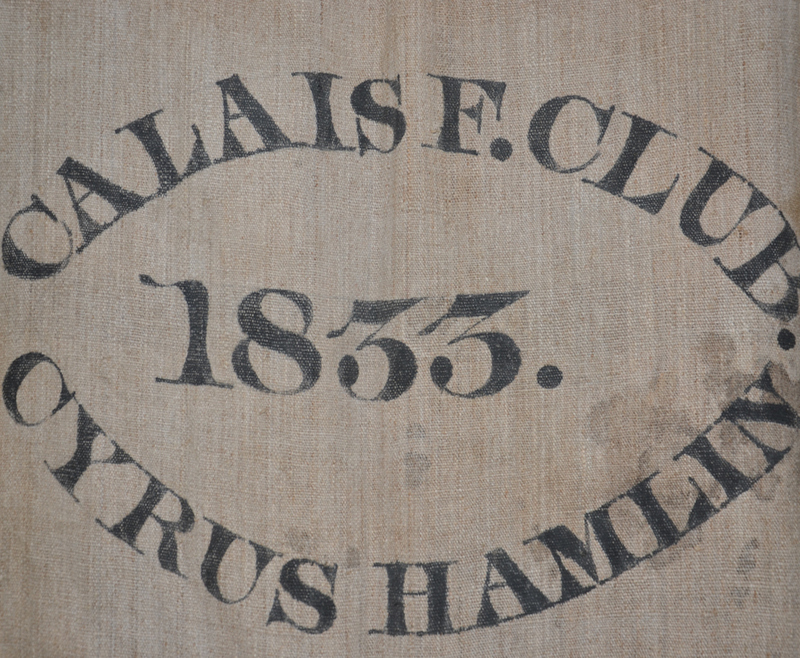

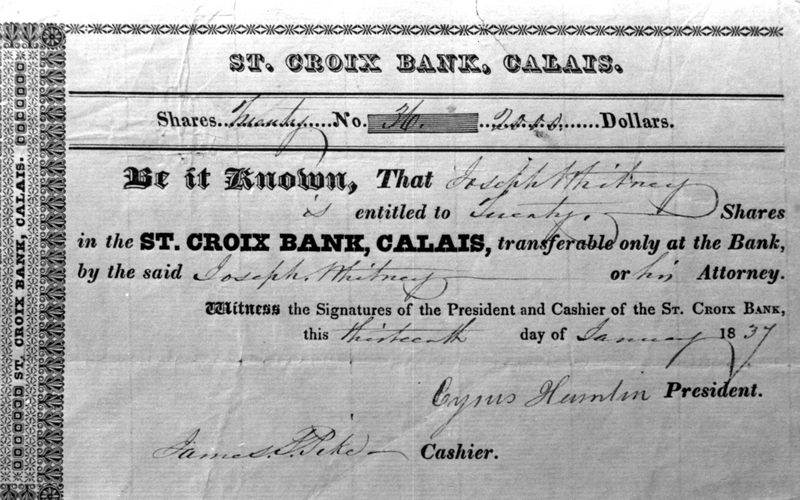

Cyrus Hamlin, the home’s new owner, was himself descended from sturdy stock. He was born in 1802, in Livermore, Maine, a town founded by his maternal grandfather. The family moved to Paris, Maine when he was just a young boy. His father’s father, Eleazer Hamlin, commanded a body of Continental minutemen which included his sons, Africa, America, Europe and Asia.As a young man, Cyrus assumed the responsibilities of the family farm. At the age of 22 however, he contracted tuberculosis, putting him in a condition too weak for this duty. He chose instead to follow in the footsteps of his father, Cyrus, who was a doctor as well as a farmer in Paris. His father would see him graduate from Bowdoin College, Maine Medical School in 1828, but died of pneumonia just a year later. He settled in Calais as a physician, also becoming for a time the president of the St. Croix Bank.

We still have at the cottage Cyrus’s fire sack, which inhabitants of Calais were required to own. When the alarm was sounded citizens were expected to rush to the scene of the fire and into the burning building to fill the sack with whatever possessions could be saved. Families also had leather fire buckets which were filled at one of the several reservoirs in town, the water thrown on the blazing building and the process repeated in a generally unsuccessful attempt to extinguish the blaze.

Cyrus’ medical practice was often limited by his frequent bouts of what in those days was called consumption. Still he was well regarded as a doctor and in one instance helped solve a medical mystery which saved many lives not only in the St. Croix Valley but throughout the country. The eminent Calais historian W.W Brown recounts the details:

Calais Advertiser June 10, 1914 by W.W. Brown

In the spring of 1835, a large number of persons in Calais and St. Stephen were taken with a mysterious sickness. The symptoms were pain in the back and weakness in the joints and partial paralysis, especially in the lower limbs.

The disease baffled the skill of all the local doctors, among whom were Dr. Whipple and Dr. Hamlin in Calais and Dr. Paddock and Dr. Weston in St. Stephen. No remedies appeared to do any good and it was estimated that over 60 persons died from the strange malady, while many others lived the rest of their lives partially paralyzed.

At this time Mr. Charles Perkins, one of the principal grocery dealers in Calais was attacked with the disease and he concluded to go to Boston and consult some doctor there. He took the speediest method of getting there which was by stage to Eastport and from there by sailing packet to Boston.

At some previous time, steamers had been running between Eastport and Boston but at this time no steamers were running.

Mr. Perkins began to improve as soon as he left home. When he reached Boston, he consulted an eminent physician named Dr. Morison. Who after examination and hearing his story told Mr. Perkins that he was satisfied that the people on the St. Croix River were eating something poisonous and advised Mr. Perkins to send home for some samples of groceries and food most used.

Mr. Perkins did so at once and upon receiving the samples took them to a chemist at Harvard College, and upon examination of a packet of brown sugar it was found to be poisonous. The secret was out.

That spring Mr. James Frink, a wholesale grocer at St. Stephen had imported a cargo of sugar from Barbadoes. It was of nice quality and had been sold to all retail dealers on the river. It had been noticed that only the rich or well to do people had been afflicted, the poor being obliged to use molasses.

At that time most of the medicine in use was of a bitter nature and required to be sweetened, which being done with sugar, the patient was poisoned with every dose of medicine taken.

As soon as Mr. Perkins returned home and informed the public of his discovery all the sugar was returned to Mr. Frick. He immediately sent to Halifax and had a chemist come to St. Stephen, who after examination pronounced all the sugar to be poisonous.

Dr. Cyrus Hamlin of Calais being about to visit the West Indies for his health was employed by Mr. Frick to call upon the sugar manufacturer in Barbadoes from whom he had procured the sugar.

On investigation Hamlin found that the manufacturer had conceived the idea of using lead caldrons instead of copper, and the syrup from which the sugar was made had remained in the lead caldrons until it fermented, in which state it absorbed the poison lead.

The manufacturer had become bankrupt and upon learning how many deaths his mistake had caused committed suicide by shooting himself.When Dr. Hamlin returned home and made his report Mr. Frick took the balance of the cargo of sugar, valued at six to seven thousand dollars, and hove it all into the river.

Dr Hamlin’s discovery was reported in the national press and other communities found similar contamination in imported sugar.

Cyrus continued to suffer from the weakness in his lungs and before he went to Barbados, he sold the cottage to his sister, Vesta and brother in law Dr. Job Holmes, who had attended medical school at Bowdoin with Cyrus.

Cyrus remained in Calais helping Dr Holmes with the practice and engaged in various business ventures, attaining the presidency of the St. Croix Bank. His medical condition worsened, however, and in 1837 his sister, writing to their mother in Paris, Maine, noted that “Cyrus has been unwell for a few weeks past. He has a cough and thought it best to take it in season and throw it off so has confined himself to the house.”

At the time, Cyrus also had good reason to be uncertain about his future in Calais. A terrible depression gripped the country and the St Croix Valley in 1837 and the bank of which he was the president failed. Many went bankrupt and there were very few who were not in financial distress. Desperate times require desperate measures, and there were some willing to chance everything, hoping to improve their dismal circumstances. Many residents of the St. Croix Valley took Greeley’s advice before it was given.

The photo above is Independence Hall at Washington-on-the-Bravos where Texans declared their independence from Mexico in 1836 and the Republic of Texas was born. Not yet a part of the United States – that would happen a decade later – and under constant threat of attack from Mexico, which declared Texas a part of its sovereign territory, this fledgling nation was recruiting immigrants from all over the world to fill its vast empty spaces.

The recruitment effort found fertile ground in the St. Croix Valley – hundreds went from this area in the late 1830s. In 1838, Cyrus, who never married, and James Swan, the brother of Dr. Swan for whom Swan Street in Calais is named, chartered a vessel, and with a full cargo and a colony of thirty young men from eastern Maine and sailed for the ‘‘Lone Star” state, arriving at Galveston, their port of destination, in December of the same year. With “Remember The Alamo” their battle cry Cyrus joined thousands of others from all over the country and the world seeking cheap land, a second chance and a new start and for some a refuge from debt collectors, Texas being then a foreign country.

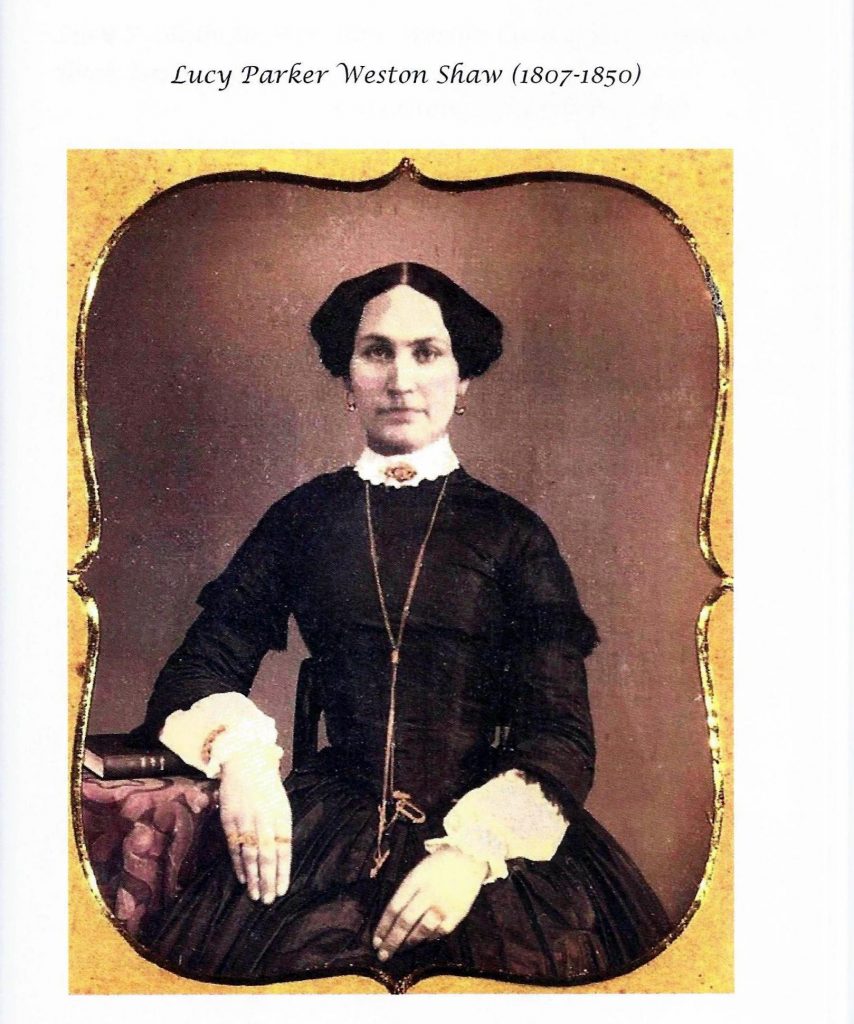

Ordinarily, we would lose track of Cyrus Hamlin and James Swan at this point. Communication between Calais and Galveston could take many months and sometimes years passed before news of loved ones was received from the distant frontier. However we are fortunate to have James Valentino’s “The Life and Letters of Lucy Parker Shaw” as a resource.

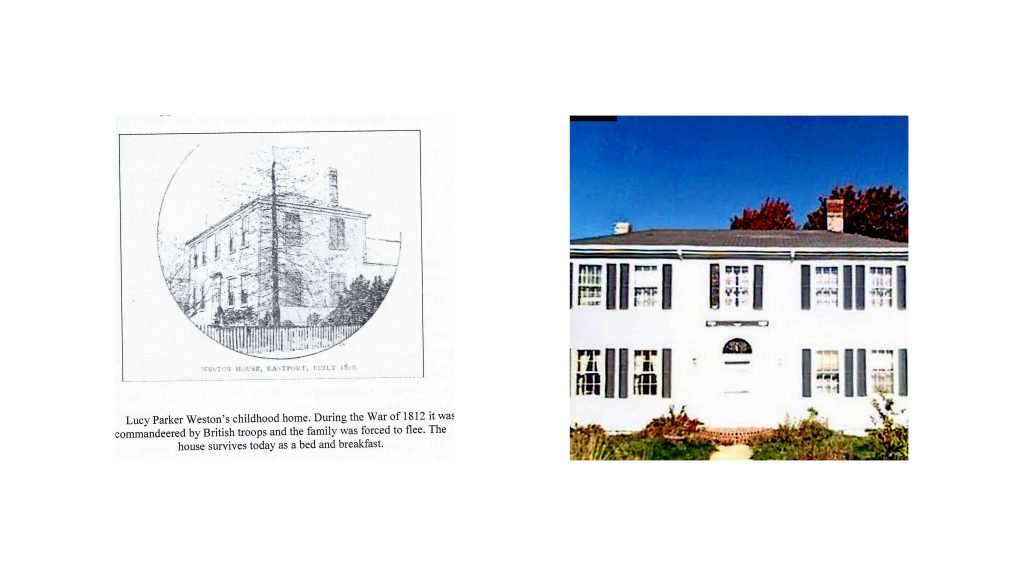

Lucy was the daughter of Jonathan Weston, a prominent citizen of Eastport. She grew up in the home her father built in 1810 at the corner of Boynton and Middle Street. It was most recently a bed and breakfast. Lucy, her two year old child and husband Joshua arrived in Galveston with a large contingent of Downeasters on December 11, 1838. Her letters home to Eastport and much in depth research is the foundation of Valentino’s excellent book. She reports regularly on Cyrus Hamlin and James Swan.

From her diary [some entries paraphrased]:

Feb 24, 1839: Lucy writes the Echo from Calais had arrived with Cyrus Hamlin and James Swan aboard. The date of arrival is unknown.Many of her letters cover long periods of time so it is difficult to date some events. The Governor Francis had also arrived from Calais. Cyrus told Lucy he had not been so well for 3-4 years but recently there had been a terrible storm and Dr Hamlin had caught a bad cold but was recovering. In the same letter Lucy says the flowers and rhubarb her mother sent by Dr Hamlin are growing nicely.

She notes Cyrus was suffering from tuberculosis and his presence in Galveston was probably to aid in his physical well being.

On March 2 1839 she notes in a letter home that the rhubarb and Tiger lilies Dr Hamlin brought were doing well as was the horseradish and rose bush.

A letter of March 31st says Dr Hamlin went to Houston but “was taken with bleeding of the lungs” and was unable to return to Galveston as he planned. He is then boarding with Mrs. Quimby of Calais

April 21st 1839: “Good many people from Calais here and Dr. Hamlin and Mr Swan are constantly hearing from home and expecting that a number will come out next fall.” Dr Hamlin is treating her brother in law James who has been ill for some time. After his return from Houston Lucy says Dr. Hamlin “ looks thinner and more feeble. I wish he was well enough to practice. He has prescribed for all of us here and seems to have skill and judgment.”

(On June 15, 1839 Dr. Cyrus Hamlin died. Lucy does not mention his death or the circumstances surrounding it directly in her letters. The authorities reported more than 200 deaths in 1839 during a yellow fever epidemic which suggests Cyrus may not have died not from consumption but yellow fever. Some historical accounts do say the cause of death was yellow fever but the obituary lists cause of death as consumption)

September 9 1839: “Mr Swan who boarded with us was taken sick and confined some weeks to his bed. He wore himself out attending to Mr. Hamlin, whom he waited upon and took care like a brother.”

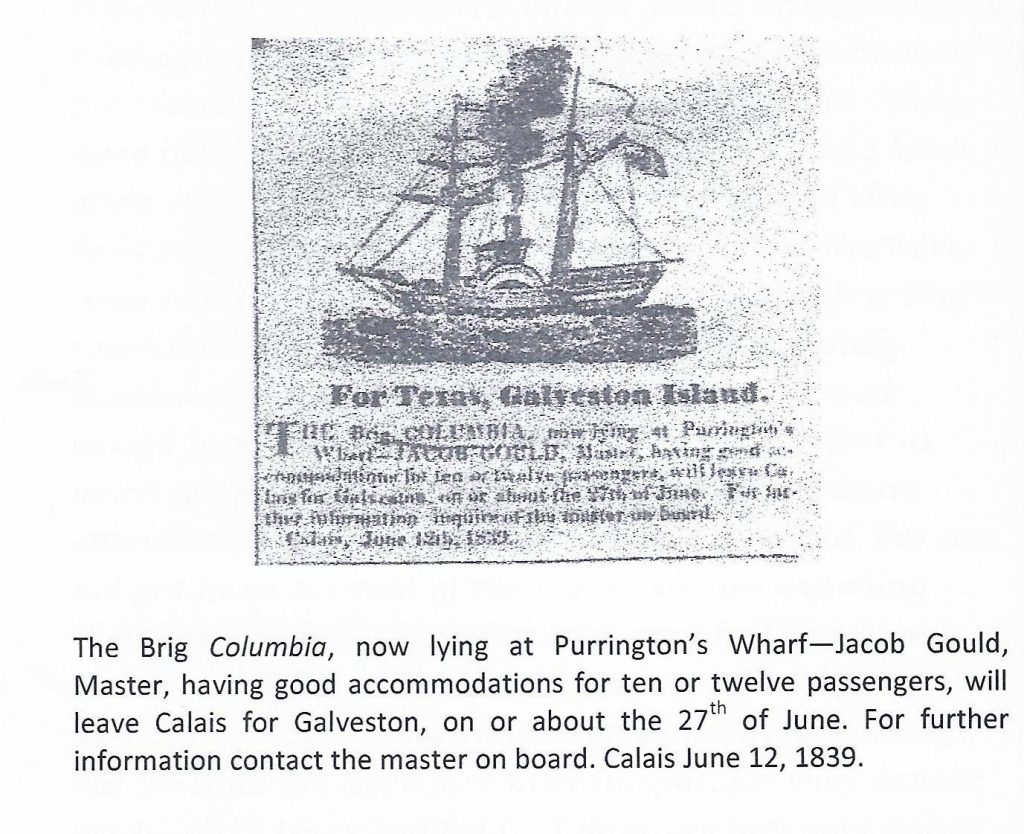

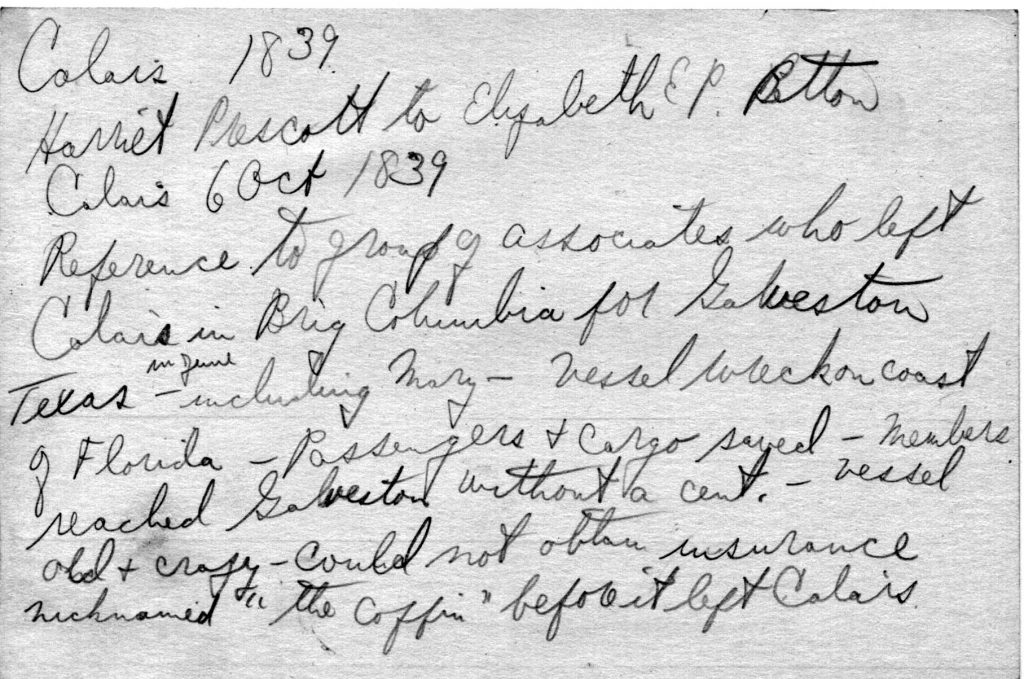

September 29 she notes the brig Columbia from Calais bound for Galveston was lost with all cargo and some of the passengers and she reflects it may deter many from coming out. Weather “Oppressively warm”

There was much distress over the loss of the Columbia. Not only was it believed some passengers drowned but all the plants, seeds and other goods the settlers were expecting and needed had gone down with the ship. In fact the passengers lost everything. This was no surprise to the folks in Calais. Below is an entry from Harold Davis’s notebook on the Calais Advertiser’s article on the ship before it sailed. The Advertiser was not optimistic about the ship’s prospects.

October 6 1839- Lucy reports Mr. Swan boarding with them and has two fine saddle horses. Columbia’s Calais passengers finally arrived but all plants, seeds lost – a heartbreaking development. She did receive a letter from Miss Hamlin of Calais, one of Cyrus’ sisters.

January 12 1840 – in a letter from a Calais friend she is advised that “times are rather hard in Calais”

March 1 1840-she reports that both Mr Swan and Reverend Darling of Calais are going home this summer.

April 21 1840 “We will miss Mr Swan very much when he goes home. He has boarded with us nearly a year and is one of the finest young men in the world. He is always the same, gentlemanly, quiet and pleasant. If all the young men from the North who come to Texas were like him there would be nothing but but harmony and good order in the country. He is 22 years old but seems to have as much firmness and decision of character was if he were an old man who had learnt wisdom by experience. He never acts from impulse but seems to always have in judgment in exercise. Dr. Hamlin’s friends ought to love and respect him, for no creature could be more faithful than he was to the last moment of the Dr’s Life.

May 21st 1840 – reports several others leaving for home. Lucy is sending two horned frogs by Mr. Swan.

The frequency of letters diminishes somewhat after the early 1840’s and her enthusiasm for Galveston appears to have waned somewhat. In her last letter she writes:

August 25 1850:

“Since the first of June the weather has been truly dreadful. Everyone complains of the heat, the consequent languor and debility and everyone looks wearied and worn out, and yet there has been no sickness. If we get through a month and a half without an epidemic it is more than we can expect…… I never knew anything as dreadful as this weather, for the nights are as hot as the days and you cannot lie down ten minutes without a mosquito net, the mosquitoes are so thick.”

Lucy died three months after writing this letter. The cause of death is not known. Her husband remarried but soon sold the “Tremont House and Saloon” he and Lucy had owned and operated which consisted of “95 rooms, two brick and three wooden cisterns and a garden – the lower story is a bar and billiard with four new and superior billiard tables…”

James Swan returned to Calais and died in the early 1850s. Whether his trials and tribulations in Texas contributed to his early death is not known. Cyrus, we believe, was buried in the old city cemetery in Galveston which was founded in 1839 after the yellow fever epidemic of that year took, in addition to possibly Cyrus Hamlin, 30% of the population. According to Galveston history, before 1839 bodies were buried in the sand dunes.

There is no stone for Cyrus in Galveston, we personally checked, but given conditions at the time a wooden cross would have been the most one would have expected. The earliest stones we found in the cemetery were from the late 1840s. The monument in Calais is probably a memorial stone although there was an instance of the body of a Calais resident being shipped around the Cape in a pickle barrel from Hawaii in the 1850s. Still it is unlikely his body was shipped home. Wherever his remains Cyrus Hamlin was a brave, intrepid and resourceful man who deserved better than an early death far from his native Maine.

James Valentino’s book The Life and Letters of Lucy Parker Shaw can be purchased here.