Pirates have never been much of a problem in this area– unless you count the privateers who plagued the Brits during our occasional wars and border controversies in the early years. There’s also John Hogg Paine, one of history’s most violent and notorious pirates who, it is claimed by the Calais Advertiser in a 1901 article, settled in Union Mills near St Stephen after escaping the noose by jumping overboard a British ship off the Carolinas as the Brits were readying the scaffold. By way of pirates, and certainly much worse in the great scheme of things, were slavers– and Calais did have some connection with them, it seems.

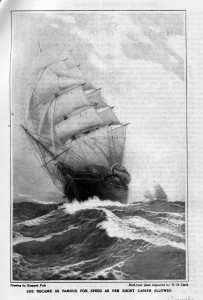

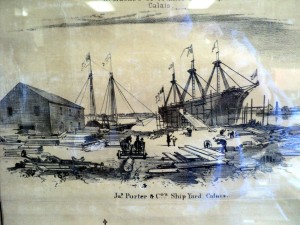

There was a 1906 article about the Calais slaver Arabian (Caribbee). The article was written for Harper’s Magazine by Thomas Briggs, a Calais man who himself witnessed the building of the Caribbee, the fastest vessel of its day, at Calais, Maine, in 1852. Briggs also watched her sail out of the home port. Briggs was related to the Porters, for whom the vessel was built by James Hinds, and it is said every fact in this narrative was verified.

Here is an edited version of the 1906 Harpers Magazine article by Thomas Briggs (for the complete article, scroll to the end of the page, or click here: Caribbee Article):

“It was shortly after the commencement of the rage for building

clipper-ships and other fast-sailing vessels, in the year 1852, that

the principal firm of builders in Calais, Maine, Porter Shipyards,

having launched one of their famous ships, in order to make an

economical use of material unsuitable for larger vessels laid down the

keel of a clipper-bark. The builder desired to attain the greatest

possible amount of speed. All the relations of length to breadth of

beam, depth of bold, also length of floor, dead rise, entrance, run,

linos, and all those points which at that time and thirty years later

were argued and debated pro and con by builders, owners, and nautical

men and writers in our principal cities, had been wisely and carefully

considered.

Her name was Arabian and when she left her wharf on the last day of June for the city of New York, her manager and master builder were on board. A large crowd of citizens witnessed her departure. A fair and gentle breeze filled her sails as she swung around into the current, and as sail after sail was hoisted and sheeted home, she soon left the “ Eastern city ” far behind. Her run down the river and bay for thirty

miles was soon accomplished. The master was sent on shore twenty miles outside. He wished to know how fast she could sail, but, said he, “ I never found out.”

The run to New York was made in four days, with head-winds all the way. She arrived at Sandy Hook on the third day of July, and on the fourth sailed up to the city, out sailing all the yachts in the bay. The pilot who took her in said she was the fastest vessel he knew of .

As a matter of course, the bark attracted a vast deal of attention.

Her unequalled performance excited the especial admiration of a

wealthy Spaniard and his Cuban captain, who were on the lookout for a

fast-sailing vessel and when she hauled into her dock on the North

River side they appeared for a nearer view, and also to get what

information they could. They were invited on board, looked her over

thoroughly, examined the log-book, got all the information possible in

an hour’s visit, and left well pleased. They were interested in

sailing-vessels, had seen the bark as she came up the harbor, and were

pleased with her appearance. She also received visits from many

others, and created quite a sensation among nautical men.”

The Spaniard bought the Arabian for $20000, a princely sum at the time and took the ship to Cardenas Cuba to be outfitted as a “slaver”. Under Captain Bazin, a Cuban, the Caribbee sailed for Guinea in West Africa, purchased a full cargo of slaves and upon recrossing the Atlantic was sighted by a fast British brig who gave chase. The nine-day chase was won by the Caribbee but the game was up as all ports had been notified of her status as a wanted slaver.

The article goes on to describe her end:

“Next morning nothing was seen of the brig, but she was believed to be

still in chase, and every effort was made to increase the distance. It

was now the ninth day. Various sails were seen, but nothing

suspicious. At noon the bark was about one hundred miles east of

Nuevitas. On the morning of the tenth day she was seen from the

highlands and her presence telegraphed by flags to Cardenas. There

everything was being made ready. The wind was more favorable. At noon

she was but little more than one hundred miles distant, and if the

wind held, Captain Bazin expected to arrive by ten o’clock p.m. He was

not disappointed. The wind held, and shortly after ten he anchored off

the town. Everything was let go by the run. The lighters were soon

alongside, and the Spaniard immediately came on board. The situation

was explained in a few words. Plenty of help was at hand. The captives

from both holds were got out and put on board the lighters as speedily

as possible. There was no striking of irons. A single stroke of the

knife liberated two. As fast as they were landed they were hurried off

in gangs to various plantations in the interior. Those who were weak

and feeble were placed in mule and donkey carts and followed. In a

little more than three hours they were all out, and soon the last gang

was sent off; and now the guns, ivory, arms, charts, men’s chests, and

whatever could be got out easily and at once were put on board the

lighters, a few sails cut from their lashings, cable shipped, the bark

taken in tow by several boats, borne out to the bar, and set on fire

in several places. Very soon she was a solid mass of flame from jib-

boom to taffrail, from truck to keelson, and a dense black cloud of

smoke rolled over the town. Soon after daybreak the brig appeared in

the offing. Her commander at once took in the situation, and presently

his departure. All that remained of the famous slaver Caribbee was a

smoking, blackened hulk.

She had landed about twelve hundred captives. “ They were considered

an extra lot and averaged one thousand each,” so said a commission

merchant from Matanzas; and also that “the owners cleared one million

dollars.” Captain John Locket carried six of the crew to New York.

They told him they “ received seven thousand dollars each.” They

ranked high and were paid accordingly.”

So ended the single journey of the Calais slaver Arabian. It was originally built by the Porter Shipyard in Calais (William Hinds was the Master Builder).

To see the entire 1906 Harpers Magazine article by Thomas Briggs, click here.