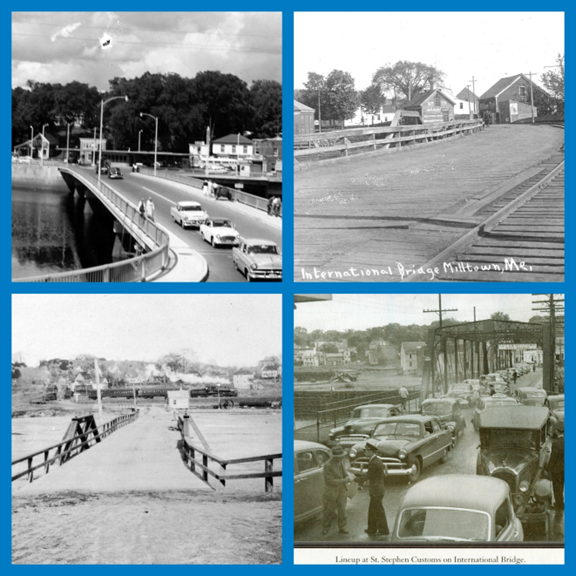

In days past Calais and St. Stephen was truly one community—everyone had close friends and/or relatives across the border which was crossed by the three bridges over the river shown above. Until the mid-‘50s the bridge at Ferry Point was the steel bridge in the lower right, replaced in 1956 by the present bridge in the upper left. There was also the Milltown Bridge (upper right) shown in an early photo and the Union Bridge lower left. A train can be seen crossing Todd Street going toward Milltown. This is where the City walkway ends today. It was no secret that a substantial proportion of the goods transported across these bridges on any given day were not “declared.” “Do you have anything to declare?” was often not considered a serious inquiry, just a question the customs officer was instructed to ask by out-of-touch bureaucrats who had never lived on the border. The answer depended on whether you had concealed whatever you were smuggling well enough to require some serious effort on the part of the officer to find it. If so, the answer was understood to be ‘No.” If purchases were in plain view, for instance the bike you just bought at Johnson’s was strapped to the roof of the car, then you had to fess up and pay duty as the customs officer had no “plausible deniability” in the event his dedication to collecting duty was questioned by his superiors. This little vignette played out hundreds of times every day on the border and being “retail,” smuggling was considered rather harmless as shown by this little ditty written by a local wag:

Oh roll me over a barrel of rum

And I’ll roll you over a barrel of oil;

We’ll laugh in our sleeve as they take their leave

And depart from their native soil.

Let prohibition and customs laws

Essay our spirits to damp.

We’ll drink success to the good old cause

By the light of the kerosene lamp.

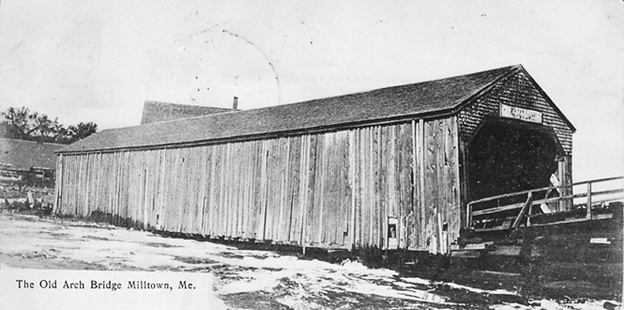

The more serious issue was “wholesale” smuggling which yielded high profits for lumber barons and other professional smugglers. Thousands of board feet of lumber, large quantities of sugar, flour, fuel, kerosene, and, during prohibition, booze . . . the list was endless found their way across the river duty- free. Smuggling was profitable because the prices of goods often differed dramatically between Calais and St. Stephen. This type of large-scale smuggling required different tactics altogether and none of the three main bridges offered serious possibilities. However, until the early 1920s there was a fourth bridge across the river which has largely faded from memory—the arch bridge at Knight’s Corner; and this bridge had some definite advantages for the serious smuggler.

No one today will remember the old Arch Bridge, but if you drive from Calais to Milltown on North Street you will find, just after rounding Knight’s Corner and beginning down the hill into Milltown, a “Bridge Street” street sign on the right. There is no longer a street, just the sign but at one time a street connected North Street with the arch bridge to Milltown N.B. and for many years this bridge was the epicenter of wholesale smuggling in the St. Croix Valley.

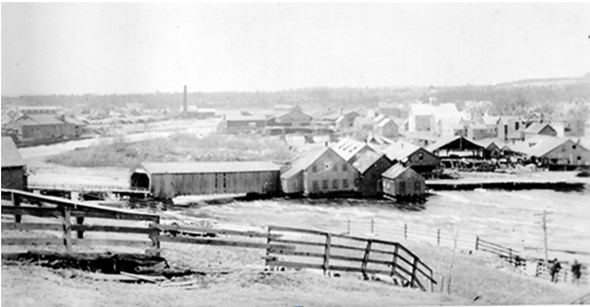

The above photo better explains the location of the arch bridge. The photographer is standing on the American side at Knight’s Corner at a point near what is now the parking lot of The Sandwich Man. Directly below the photographer but not visible in this photo are the Murchie mills. To the right is Milltown, N.B., and the top left shows Milltown, Maine. The tall stack center left is on the water company building which is still standing minus the stack across from US Customs at the Milltown Bridge. The mills to the right of the bridge are on the Canadian side and are built over the river.

According to Ned Lamb:

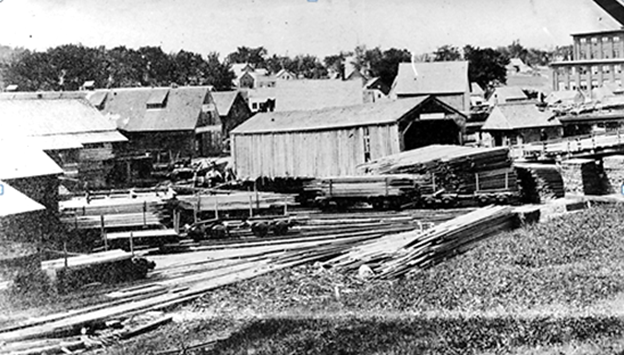

The Old Arch Bridge was built in 1826. This bridge was really in two parts. The covered part was over the swift part of the river. Connecting it with the Maine side was a high part so that the trains of the St. Croix and Penobscot, and later, the Washington County R. R’s could pass under. The further end was a long platform in front of the mills. At one time there were two axe factories, long lumber mills, shingle and lath mills, machine shops, and grist mills. This photo shows the Arch Bridge connecting to the mills below Knights Corner in 1897. The mills stretched entirely across the river from the US shore to Milltown N.B. It was impossible to stop lumber from Canada or anything else for that matter being freely transported from one side of the river to the other and it was very profitable to do so. Lumber shipped from Canadian mills was subject to high English duties but was duty free if shipped from the Calais side.

Murchie’s millyard

The Murchie mills, shown in this photo, cannot be seen in the previous photo because they were below the steep bank of Knight’s Corner, but the Murchie Mills and the mills straddling the river on the Canadian side represented one of the largest concentrations of lumber and milling operations on the river. The Cotton Mill can be seen top right. As Ned Lamb notes it was as easy as a short trip across the arch bridge to convert “Canadian” lumber into “American” lumber. Customs officers were sometimes assigned watch to the bridge but enforcement was sporadic. Unless the enforcers had a tip, the arch bridge was often a free trade zone. Even when they had a tip it sometimes did not go well for the revenue men. Consider this incident described by Ned:

Vain attempts were made now and again by revenue agents to stop the smuggling. There exists an account in 1837 of a customs seizure by Customs Officers at the Arch Bridge just below the Boundary House, based on a tip from an informant. A group of concerned citizens from both sides of the border thought it only right and proper that the name of the informant be made public in order that some remedial education on the economic realities on the river be given this, as the newspaper put it, “odious villain”. The Customs Officers refused to divulge his identity whereupon the citizen group, disguised as Indians, kidnapped the pair and escorted them across the river to a pine grove at the rear of the William Todd residence in Milltown N.B. A lengthy discussion ensued between the “Indians” and the Customs Officers, and menacing scenarios were advanced as to the fate of the officers should they refuse to yield the name but in the end the “Indians” went home without the informers name and the Customs Officers without injury.

The affair caused a stir; the militias on both sides of the river were called out; but the newspaper reported “Order was soon restored, but none were ever brought to justice. The actors in the affair were men of immense muscle. They were the very hardiest race of men in existence. Almost certainly some of these men of muscle had close connections to the Boundary House.”

The Boundary House was located on North Street at the top of Bridge Street just above the Baptist Church on the way into Milltown. It was notorious as a haven for smugglers and other renegades and often provided a meeting place for those planning to move large quantities of lumber or other contraband across the river. During Prohibition it was usually on the list of local establishments to be raided by the authorities.

It was not, as far as we know, ever closed down by the Feds or the State, but then raids were seldom a surprise to the “rumsellers” who had contacts both in local law enforcement and in the county sheriff’s office. The arch bridge was also used by regular folk to smuggle the cheaper necessaries of life across the border in both directions. Ned lamb relates this incident:

‘Twas in the days of the Old Arch bridge and there was a customs man for the Upper Bridge, to whom we will give the name as Mr. Big, while the man at the Arch Bridge we will call Mr. Small. You can call them by any names you like. One evening Mr. Small wanted to go away for a while and he asked Mr. Big if he would go down to the Arch Bridge once in a while. Mr. Big said he would be glad to do so, and then proceeded to forget it until his supper time. Then he went down that way, keeping in the shadows. Just as he neared the Bridge he saw two men with the forward wheels of a truck wagon on which they had a barrel of kerosene. One was pushing and the other was pulling. Mr. Big did not say anything but stepped up near the man pushing. The rear engine did not say a word of warning to the front part but just ran. Mr. Big stepped into his place and pushed. The new combination worked smoothly and soon the kerosene was up on the main street. The man in front stopped to catch his breath, looked around, saw who was helping him, and he too ran, leaving the barrel in the possession of the officer. It was only a little way to the officer’s barn where he always stored the things he seized and went in to his supper.

After supper, Mr. Big opened his back door and there were the two would-be smugglers trying to open the barn door. The officer did not make any noise but went to the edging pile—there was always one in every yard is those days—and picked up a lath, crept up to the barn door; and brought the lath down with a resounding smack. The two let out some yells and did not stand on the order of their going, but simply went across lots, over fences in the general direction of the Arch Bridge, with the officer right behind them. Every time the officer got the chance he brought that lath down on a building or fence. The chase ended when the two got half way over the bridge, and then they turned around and shook their fists and called the officer all sorts of fancy names for trying to shoot them.

“Them were the happy days.”

The arch bridge was also a shortcut for US residents who worked at the Cotton Mill in Milltown, N.B. Hundreds crossed every day including Joe and Gert Donovan who lived at the Union.

Phil and Edna Donovan of Meddybemps are longtime residents of the area. Both were born in Calais, Phil in 1918 and his wife Edna Stanhope in 1922. Phil has some interesting memories of the Cotton Mill, the Depression and the length folks had to go in the 1930s to survive. Phil’s father and mother, Joe and Gert worked in the Cotton Mill in Milltown N.B. as did his Uncle Jack’s wife Annie and hundreds of others from the U.S. side. The Donovans lived in the Union and in the early 1900s walked over the old arch bridge or the trestle six days a week to work as spinners, weavers and loom fixers at the cotton mill. By the time Phil was born in 1918 the mill was experiencing labor troubles and increased competition and hours had been cut from 57 to 50 hours a week. In 1923, when Phil was five, the mill was nearly destroyed in the flood of 1923, and the owners found it difficult to raise the money needed for repairs. By the early ‘30s the owners were forced by the Depression to institute a policy of job preferences for residents of Milltown, N.B., and the Donovan clan and hundreds of others found themselves unemployed.

The arch bridge met its end in the flood of 1923. The bridge and the ramp leading to it can be seen at the center of the photo, badly damaged. The decline of the lumber industry and financial problems at the Cotton Mill resulted in a decision to abandon the bridge, and it was not repaired. The era of wholesale smuggling had passed and there were no longer lumber barons who could make fortunes by converting a Canadian log or board to an American one. That era had ended even before the flood of 1923 took out the arch bridge. Even so, many were sorry for the loss of such a convenient shortcut across the river.