Postcard circa 1920

We have had inquiries recently with questions about Milltown- is it part of Calais or a separate town, did it ever have its own government, police department, etc. and where does Calais end and Milltown begin? We have done some research and can answer most of these questions, but some are more complicated than others.

We’ll start first with the easy one-Milltown was always part of Calais even before Calais was Calais because in the late 1700’s both were tiny Massachusetts settlements clinging to shore of Township Five on the Schoodic River. The villages were then known as Stillwater (Milltown) and Saltwater (Calais). Massachusetts sold Township Five to Massachusetts politician Waterman Thomas in 1784 and by the early 1800’s Township Five had incorporated and named itself Calais after Calais, France because just across the river from Saltwater Village (Calais) was Dover, an early name for St. Stephen.

Drawing 1805 showing 1st mill at Milltown, the Brisk Mill. Many more to follow.

By this time the first mills were being erected on the river at Stillwater(Milltown) and bustling communities were developing on each side of the river being called, unsurprisingly, Milltown, Maine and Milltown, New Brunswick. The drawing above shows Milltown Maine at the bottom and in green are the two islands in the river just below the bridge on which later mills were built. These two communities became the economic engines of Calais and St. Stephen. Without the Milltowns there would have been no lumber barons, no Todd, Eaton, Murchie and Boardman fortunes, elegant homes in Calais and St. Stephen, Opera Houses, lovely churches on tree lined avenues or stock farms breeding world class racing horses. We should point out that except for some nice churches, none of the above were to be found in Milltown Maine. Milltowners are known to have a chip on their shoulders and not without justification. The fortunes made possible by their blood, sweat and sometimes deaths in the lumber mills flowed, like the St. Croix, downriver to Calais and St. Stephen.

The Duren and Gates Mills were built on the island just below the Milltown Bridge

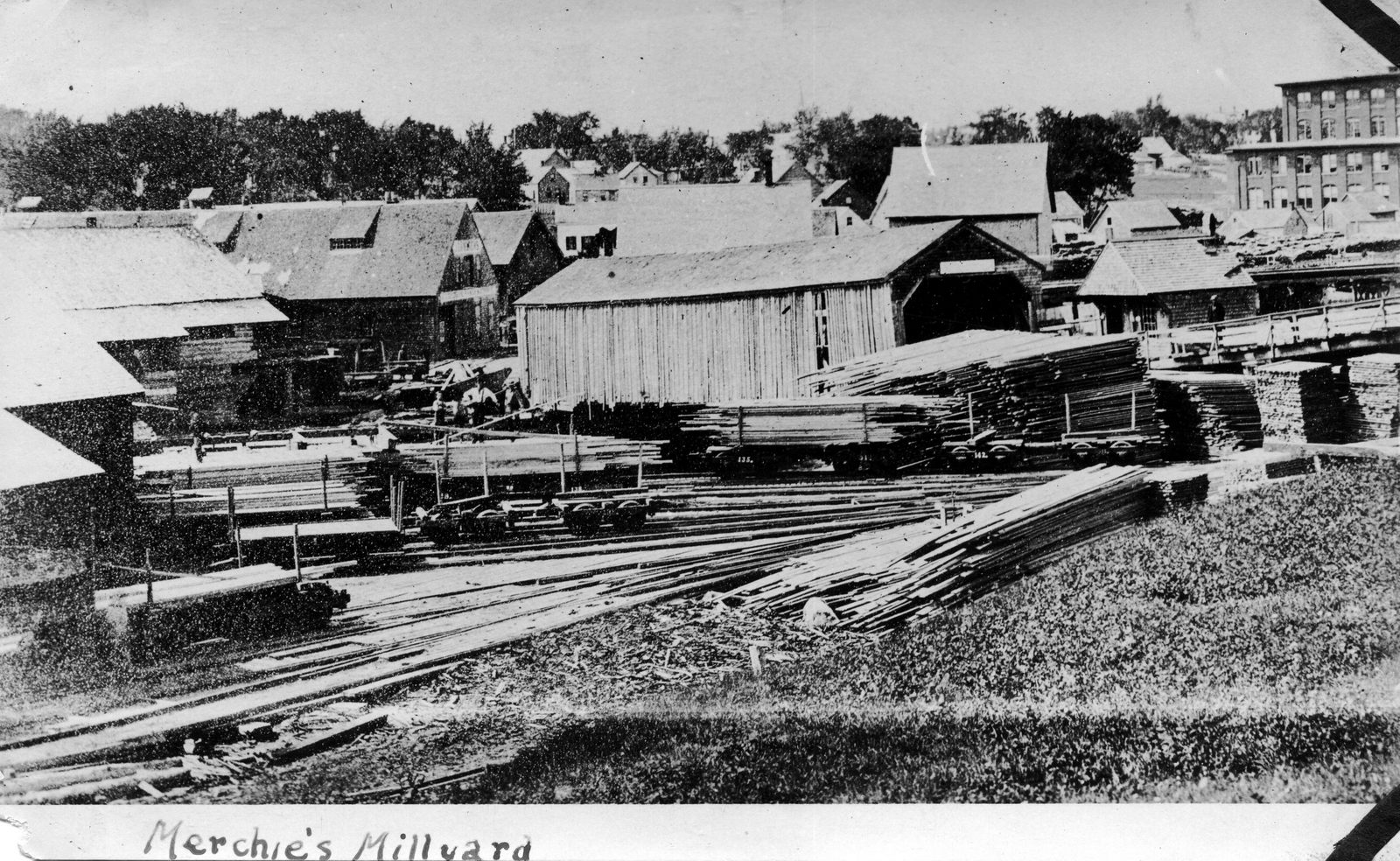

The Murchie Mills were at Knight’s Corner, to top right can be seen the Cotton Mill

From just below the Milltown Bridge to Knight’s Corner the hum of mills was constant so long as the Schoodic, now called the St Croix, was strong and the mill pond above the Milltown Bridge was full of logs. It is worth mentioning here that only a quirk of nature saved our valley from destitution. If one were to stand in the middle of the Milltown Bridge and look upriver the view would be many acres of still water, a vast pond. On the other side of the bridge, downriver, the river drops but not dramatically and probably not enough to generate the power needed to run nearly a dozen sawmills.

By 1874 Milltown was booming. Most of the mills were on the islands in back of Clark’s Store in Milltown

However just below the Milltown bridge are two Islands which channel the water into three branches and on these funnels the folks in both Milltowns built the mills that made some in the St. Croix Valley very rich. The mills were built on the islands and reached by bridges from the shore. The main bridge was an extension of Chase Street in Milltown which ran below by what we know as Clark’s Store and over the river onto the large island in the photo above. The cement and rock foundations of the old mills can still be found on the island as can a nice grist stone from the gristmill.

1874

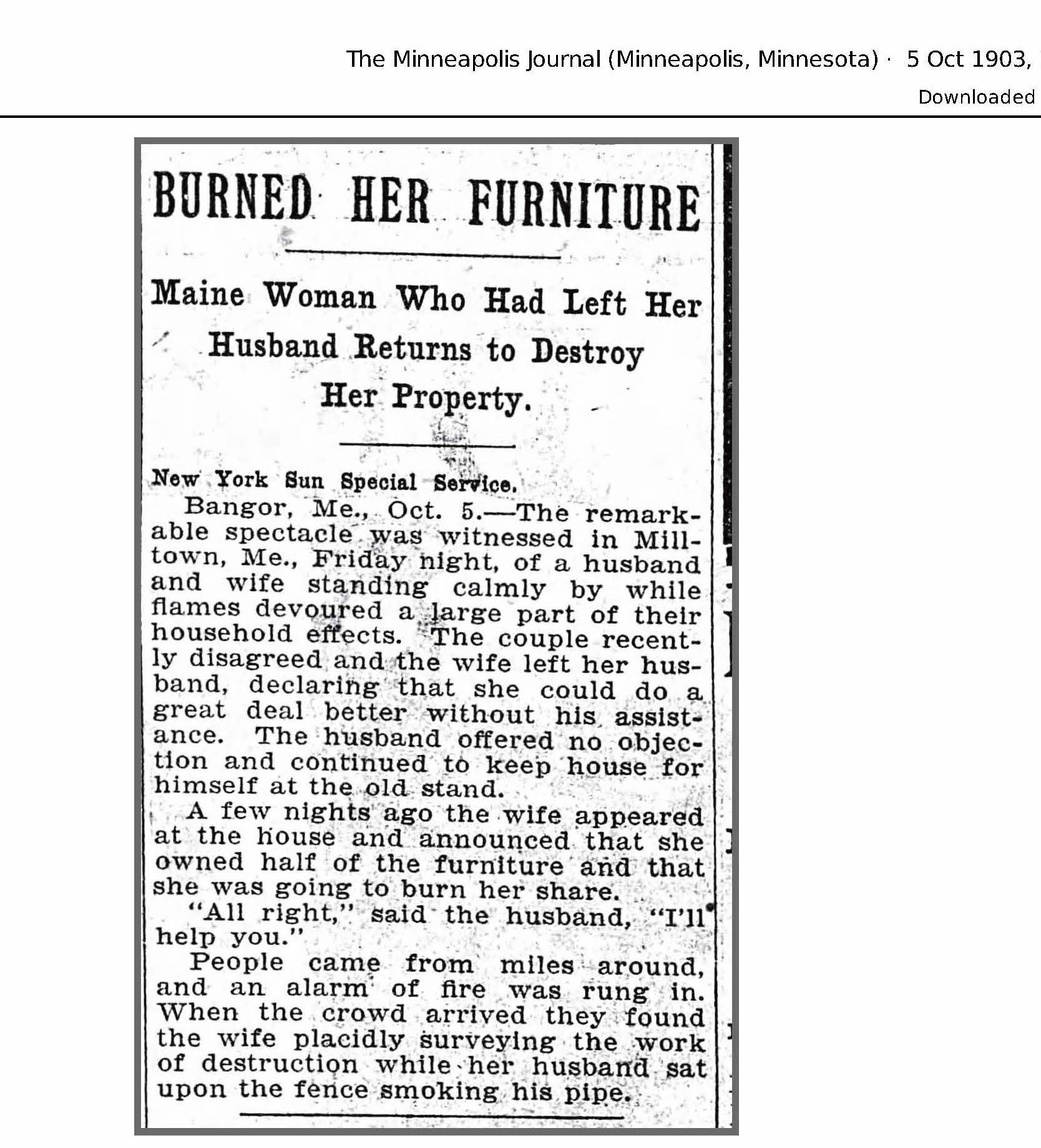

Work in the mills was hard and dangerous; the hours were long and sometimes not very dependable. Exposed belts, gears and pulleys moved rapidly to power enormous gang saws whose unprotected blades could turn enormous logs into lumber with dispatch. The noise was deafening. Injuries were a daily occurrence and death not unusual. Consider James Hicks of Milltown who in 1891 may finally have been put out of work for good.

He Worked in Sawmills

James Hicks of Milltown Me still lives despite a series of the most terrible accidents. He has just had the toes of his right foot amputated Thin was only a trifle for him as the toes of his left foot were cut off long ago followed finally by the whole foot He has been mangled in a lathe machine struck by bolts flying from the saw and nearly killed had his ribs crashed by slabs from a bolting machine, nose broken, scalp partly tom off by being drawn over a pulley back and shoulder scolded in a boiler explosion and received other injuries of more or less importance. He may lose the right foot now which would incapacitate him from further work in sawmills.

Children of all ages worked in the mills and suffered accordingly:

There was no hospital in Milltown or Calais to treat those injured in the mills. Dr. Hartford Knowles lived for many decades on Milltown’s Main Street in a home of 25 rooms and within shouting distance of the mills. A surgeon in the Civil War, his experience came in handy in Milltown. It is claimed by historian Ned Lamb that Knowles performed the first appendectomy in history in 1875. After learning a patient in Pembroke was dying from appendicitis he sent his assistant to Peck’s Drug Store in Milltown NB for a supply of ether and rushed to Pembroke. Telling the man’s wife her husband would die unless the appendix was removed immediately, he received her consent, administered the ether and performed the successful operation.While the operation was not, it seems, actually the first appendectomy it was still a notable feat for the times. Knowles also manufactured his own liniment which he sold commercially.

Wages in mills were low given the difficulty and danger of the work and as unions were not allowed to organize, the workers were at the mercy of the lumber barons who colluded to keep wages low and had no interest in improving safety or working conditions. Even so there were occasional strikes which the wealthy mill owners simply ignored until the workers were destitute. They were then allowed to return in some cases after a cut in pay. If the water was low or there were no logs to be sawed the men were simply told to go home and pray for rain. Praying for rain was no problem. Milltown had churches of every conceivable denomination except Catholic. The Catholics however had only to cross the bridge to Milltown NB which had an active congregation.

In August 1923 all of the Milltown mills went up in flames. The men are standing on the bridge that crossed the channel to the mills.

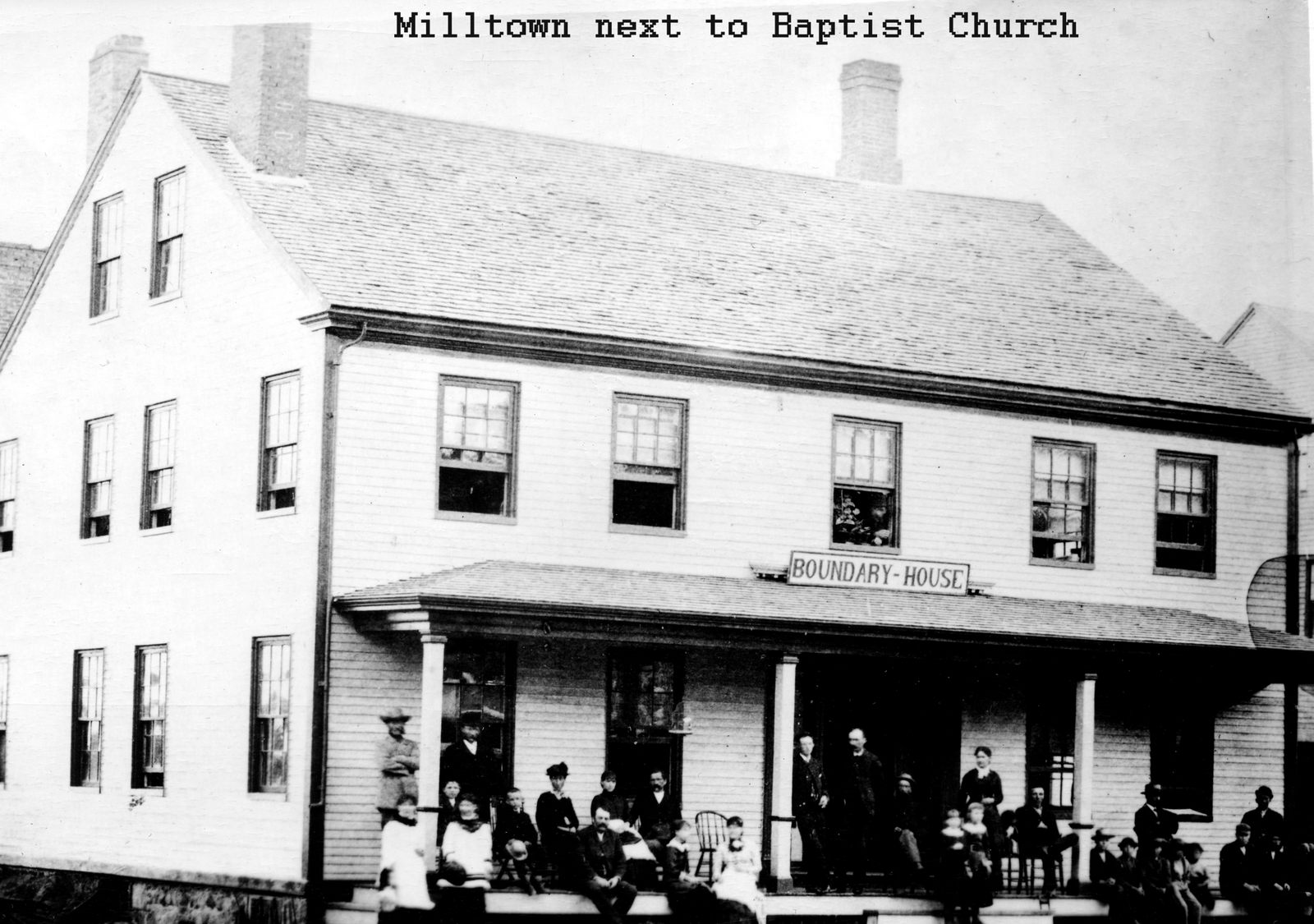

The Boundary House about 1890, Milltown’s most famous and infamous hotel.

One might question how Milltown folks survived under such circumstances. Was there no way to make a living which did not depend on the mercies of the lumber barons? In fact, there was one enterprise open to any able-bodied man or woman which was at once profitable, tax free and very lucrative-smuggling. The two Milltowns were in different countries and there were often substantial differences in the price of basic commodities such as sugar and kerosene. Further there was a customs duty on most goods going either way across the border not to mention a total prohibition on alcohol in Maine from the 1870’s until the end of Prohibition in the 1930’s. Not only did Milltown have two bridges conveniently located for smuggling but it was possible to cross from shore to shore through the lumber mills. Needless to say, tax- and duty-free commerce was the rule not the exception. The Boundary House shown above was notorious as a smuggler’s den and often figured in the occasional raid or customs crackdown. It was located on the river side approaching Milltown from Knight’s Corner near the entrance to River Street which connected to the Arch Bridge.

People who informed on smugglers to customs officials risked quick retribution.

From the Mississippi Free Trader (Natchez Mississippi) July 6, 1843:

Another border outrage.

The Calais (Maine) Journal records a recent outrage at St. Stephen. A young man, named Tobin, falsely suspected of having informed at the customs house against some leather belonging to W. E. Colwell, a shoemaker, in Milltown, was seized, carried across the border into New Brunswick, stripped of his clothing, and tarred and feathered. The Journal says he was seized at the toll-house on this side, by a party of men in disguise, and conveyed, to use the language of the Spectator, in a style “more rude than fashionable,” across the bridge, into the province, to a field owned by R. M. Todd, Esq., where, without heeding his protestations of innocence, he was stripped of his clothing, thrown upon the cold ground, and in that condition was compelled to remain for an hour.

He was then tarred and feathered, and the process of shaving performed on his face, which consists of tar as lather, roughly put on with sticks, and then scraped with some rough instrument. These outrages perpetrated; he was left to take care of himself. He was, by the kindness of a friend, assisted to the house of Mr. Butler, cold and exhausted, where every attention was paid to him which his condition demanded. Such are the statements of ” Spectator,” which are unquestionably true, and we may as well state here, that Mr. Tobin has the certificate of the custom-house officer, to the effect that he was not the informer. The probabilities are, that the outrage was perpetrated by citizens of the province.

The Calais Advertiser commented on similar incident a few months later:

We understand that the Customhouse officer made a seizure of a gondola loaded with laths on Monday evening last. This was doubtless the work of an informer, and whoever he was we hope he will receive a suitable reward for his pains. If it was the person we judge it was, we are sure he is just mean enough to be guilty of such a base and contemptible a transaction; —and all we wonder at is how he has kept his rascality so well concealed so long. But “murder will out”.

The paper’s attitude toward informers was not surprising. Smuggling was not considered a crime on the St. Croix but a fundamental right.

There exists an account in 1837 of a customs seizure by Customs Officers at the Arch Bridge just below the Boundary House based on a tip from an informant. A group of concerned citizens from both sides of the border thought it only right and proper that the name of the informant be made public in order that some remedial education on the economic realities on the river be given this, as the newspaper put it, “odious villain”. The Customs Officers refused to divulge his identity whereupon the citizen group, disguised as Indians, kidnapped the officers and escorted them across the river to a pine grove at the rear of the William Todd residence in Milltown NB. A lengthy discussion ensued between the “Indians” and the Customs Officers, and menacing scenarios were advanced as to the fate of the officers should they refuse to yield the name but, in the end, the “Indians” went home without the informer’s name and the Customs Officers without injury.

The affair caused a stir, the militia on both sides of the river were called out but the newspaper reported “Order was soon restored, but none were ever brought to justice. The actors in the affair were men of immense muscle. They were the very hardiest race of men in existence.” Certainly, some of these men of muscle were Milltowners.

For historical accuracy we must admit some of these old tales may be exaggerated or conflated but there is no question informers were treated brutally if discovered.

A local wag and aspiring poet wrote the following ditty about the Arch Bridge below the Boundary House:

Oh, roll me over a barrel of rum

And I’ll roll you over a barrel of oil;

We’ll laugh in our sleeve as they take their leave

And depart from their native soil.

Let prohibition and customs laws

Essay our spirits to damp.

We’ll drink success to the good old cause

By the light of the kerosene lamp.

Milltown New Brunswick Main Street about 1920

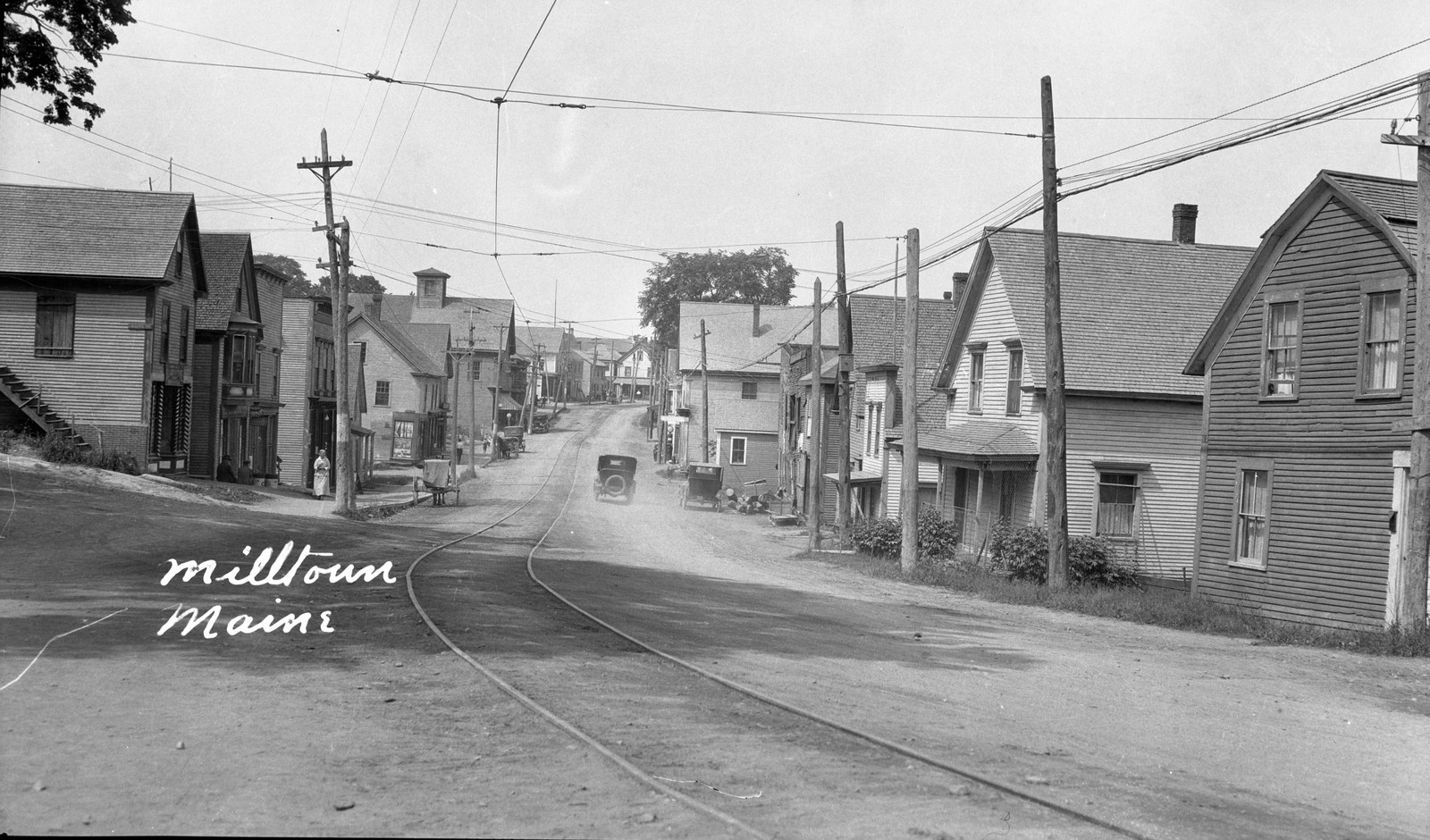

Milltown Maine Main Street early 1920s

One of the mysteries of the two MIlltowns is why Milltown NB developed as a far more prosperous village than its cousin across the line. Milltown NB was home to lovely tree lined streets, very impressive homes built and occupied by some of the lumber barons and municipal facilities that rivaled those of Calais and St. Stephen. The difference is probably explained by Milltown NB’s legal status as a separate town and therefore its right to tax and invest in the community. Sadly for Milltown, Maine it had to rely on the generosity of Calais taxpayers to fund Milltown’s basic services. The political power rested with the lumber barons who made their money in Milltown but lived, worshiped and shopped in Calais. Even Ephraim Gates who as a Milltown man made a fortune in Milltown moved to Calais to build his trophy home on North Street, the first with running water in the St. Croix Valley. In recent years it was the Mecca.

Still, we suspect that Milltowners didn’t care much if the “upper crust” preferred Calais to Milltown. Their community was doing quite well. Milltown kids went to grade school and high school on School Street in a building which was identical to the Calais Grammar School. Hose 2 of the Calais Fire Department was located on Boardman Street and both a constable and night watch were specially assigned to Milltown. There was also an Opera House on Boardman Street which, although a pale imitation of the one in Calais, provided a venue for dances, athletic competitions and town events. A 1902 article in the Bangor Daily reports that John Frost of Eastport and Ernest Kirk of Milltown were pairing off in a one-mile roller skating race at the Opera House to determine the Eastern Maine champion. An orchestra was to play at a dance after the race.

The “People’s Hall” over the store at the corner of Chase Street was home to many civic organizations, debating clubs and social events. The Milltown churches were extremely active and not afraid to tackle contentious issues such as slavery. The invitation from a church in Milltown to an abolitionist speaker caused great controversy and much criticism from the more staid, conventional clerics and a near riot when the abolitionist attempted to speak in Calais.

If they had a reason to go to Calais, Milltowners could have easily taken the streetcar or, before the streetcar, the horse drawn taxi that plied the Calais-Milltown route in the late 1800’s. Milltown had its own shoemakers, livery stables, attorneys, drug stores, confectioners, tailors, clothing and dry goods stores. As noted above the village had lodging houses such as the Boundary House. Downtown the “Golden Rule Hotel” catered to those who preferred a quieter setting. They also had Ned Lamb, Calais’s preeminent historian, who for many years wrote a regular column in the Calais Advertiser titled the “Milltown Diary” which reported in some detail the news in the village. It is fair to say residents of the St. Croix Valley knew more about what was happening in Milltown, Maine than they did in their own backyard.

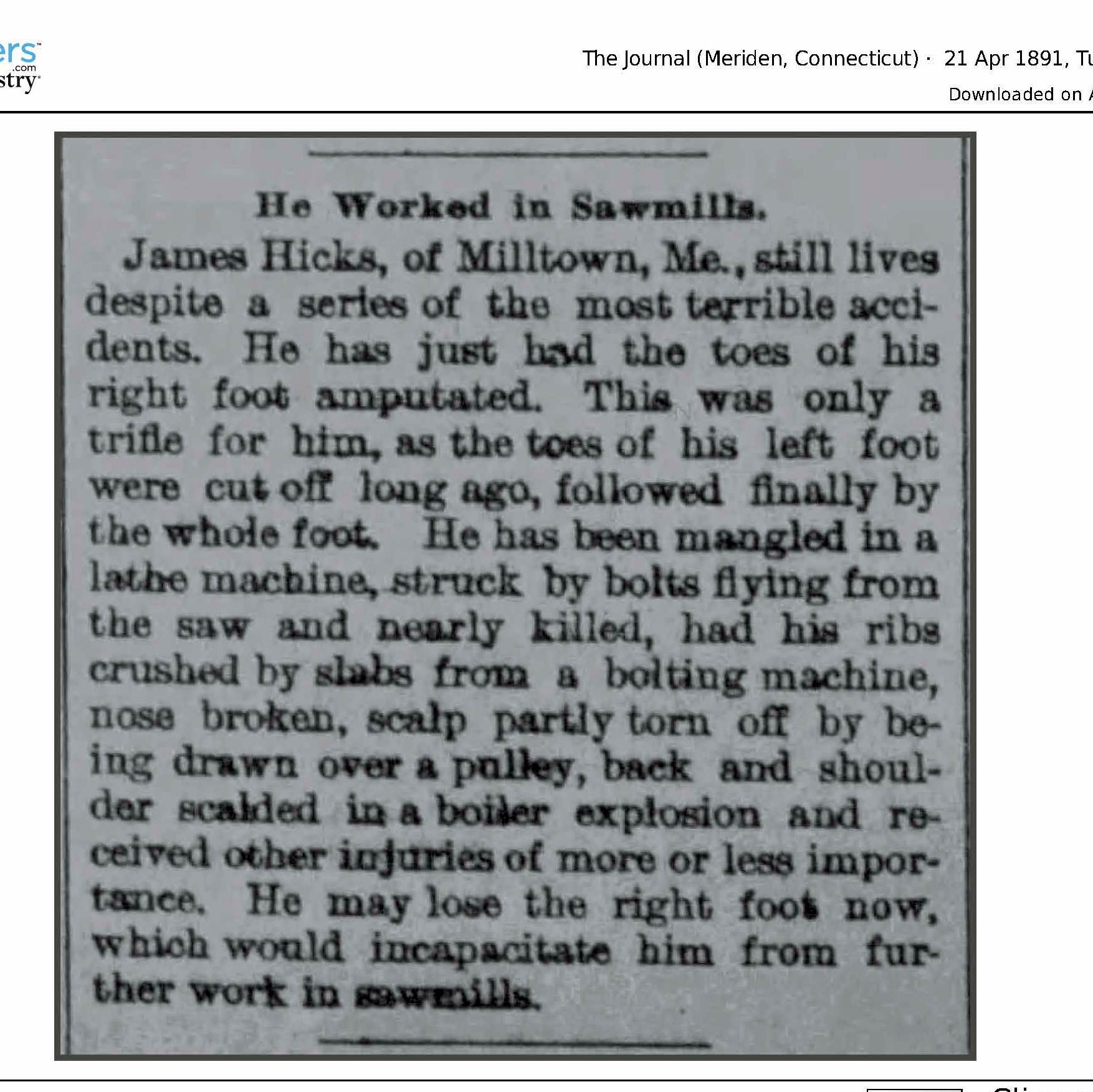

Milltowners had a direct way of dealing with tricky legal issues:

Milltowners could be remarkably blasé about suspicious deaths. From the Fall River Evening News, October 8, 1887:

Henry Purrington, a well known character in Milltown, Me, about 28 years old, was found in his bed this morning with his throat cut. No cause is known.”

Nor did skeletons much upset the daily routine. In 1924 the Boston Globe reported that a couple of Milltown boys had, while out hunting, discovered the skeleton of a boy about 12 years old. The skeleton, it was thought, had been there about three years. “Inquires are being made to discover what boy may be missing.” Nothing more was reported on the boy.

From Paper Talks magazine

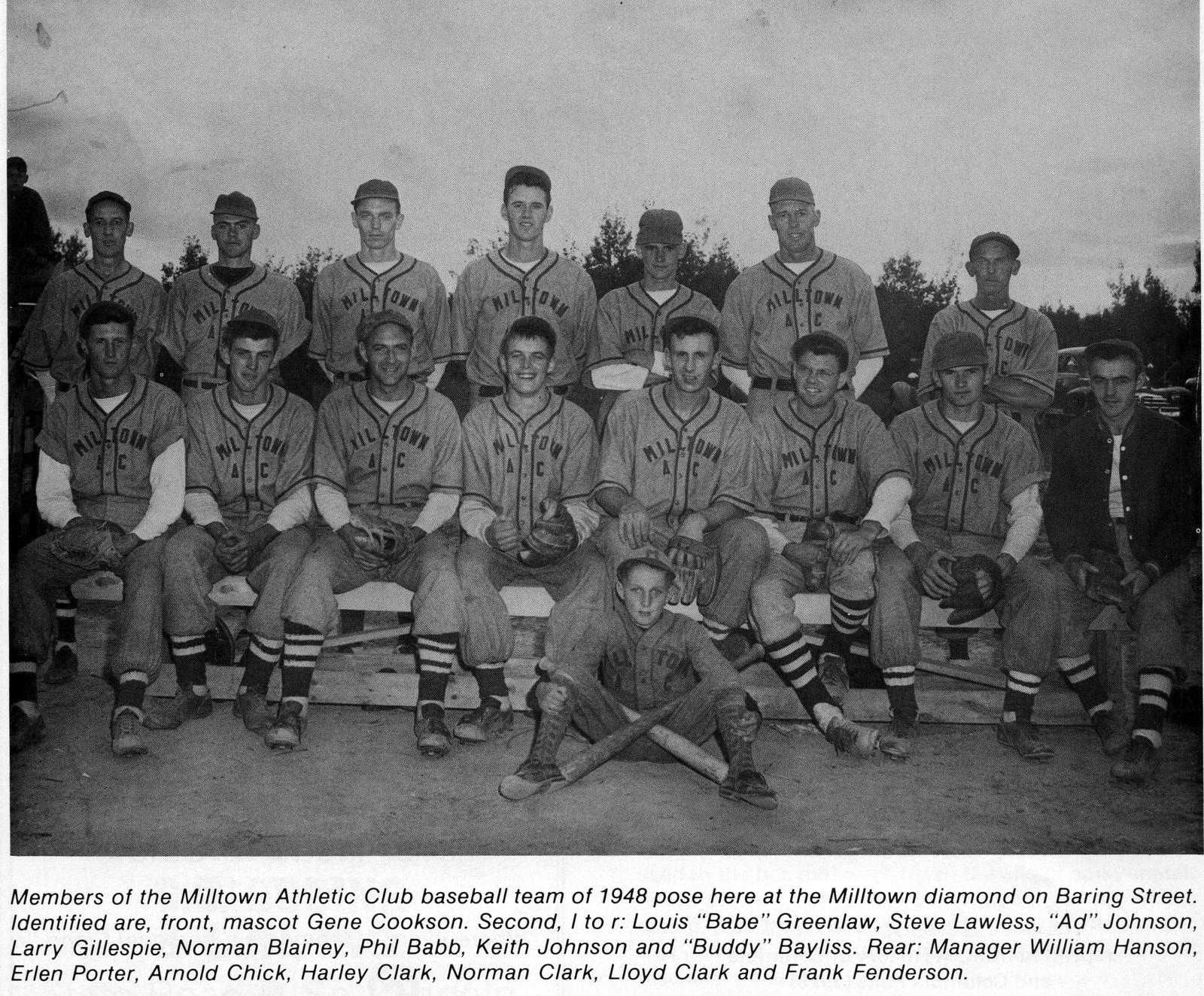

From the early 1900s until the 1950’s Milltown produced some exceptional athletes and when semipro baseball was big in the early part of the 20th century, Milltown teams were very competitive.

Milltown a few decades ago

Of course, Milltown has changed almost beyond recognition even from the photo above which is itself several decades old. Very few buildings remain on Main Street, but this is the case with much of small-town America. Only a handful of businesses remain in Milltown and those on Main Street in Milltown list their addresses in the telephone book as North Street Calais, not Milltown. The old families, Clarks, Woods etc. are still listed as Milltown in the directory as are many on the side streets but there are fewer with each new telephone book.

The school was closed decades ago and burned June 5th, 1966. The Post Office survived a bit longer, being in Clark’s Store for a couple of decades. Eleanor Clark says Sam Saunders, then the Calais postmaster, was responsible for keeping the Post Office open well past its life expectancy. She still has the post boxes in the old store.

As to who could claim to be a “Milltowner” there is some question. Certainly, if you lived near Knight’s Corner or beyond towards Milltown you were a Millowner. On the South Street side, the unofficial division line between Calais and Milltown was probably near Harrison Street although both John Wood and Theresa Porter say it was the cemetery. Until recently it didn’t matter much as there was little between Harrison St and the cemetery except woods. Now with the advent of Walmart, the courthouse etc. we think most would agree this area is Calais. The area of some dispute is between the fire station and Knight’s Corner. Theresa says at one time those who lived beyond the fire station voted in Milltown so that might give them “Milltowner” bragging rights, but true Milltowners would probably have treated that claim with some derision.

Of one thing we are sure-there are plenty of hard core Milltowners left. As Eleanor Clark told us recently “As long as I’m living there will be a Milltown!”