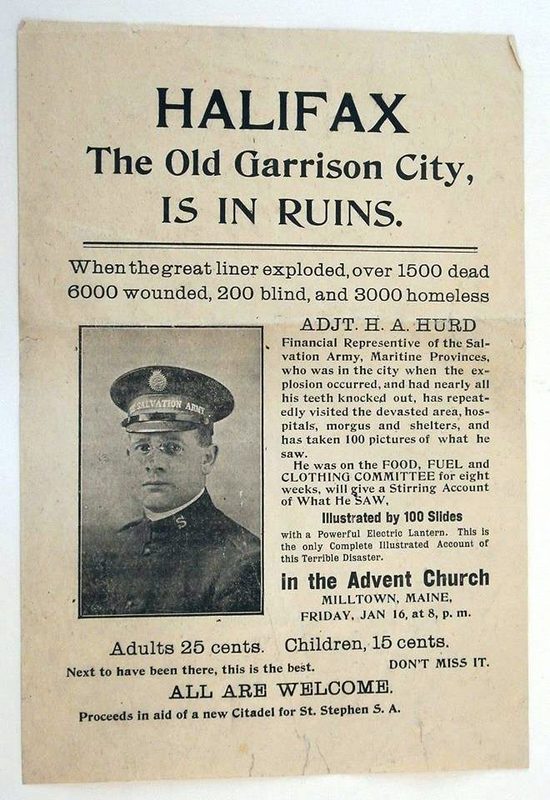

It would be impossible to condense the last year of the Great War into anything of manageable length even in a local history but as the the St. Croix Valley was far more than an disinterested observer of the momentous events of 1918, we thought it important to at least touch on the highlights. 1917 had ended with the tragedy in Halifax harbor where much of city was destroyed and thousands killed and injured when an ammunition carrier destined for the Allies in Europe exploded in the harbor. Aid was rushed to Halifax from all over the east coast including the St. Croix Valley, and the disaster brought the horrors of the war quite close to home. Reports from the city were a news staple for many weeks, especially first-hand accounts. On January 16, 1918, the Advent Church of Milltown Maine hosted an “Electric Lantern Show” of slides of the disaster with narration by a Salvation Army man who lost nearly all his teeth to the explosion. The presentation began a year which was dominated by events in Europe and found men from nearly every town, city and village in the St. Croix Valley on the front lines facing the final, desperate German offensive of the war. Of course, our neighbors in Charlotte County had already been in the war for three years and had suffered staggering losses in the trenches. In 1918, Americans, including many from Washington County, were to get their first taste of modern war.

German hopes for victory in 1918 were encouraged by the surrender of Russia to Germany on March 3, 1918. The Russian capitulation freed millions of battle-hardened German soldiers for transfer to the Western Front in Europe and was a consequence of the overthrow of Russian Czar Nicholas and his execution by the revolutionary forces. This sad event was described in The Calais Advertiser:

Given two hours to prepare for his end, Nicolas Romanoff, former Emperor was taken out by his executioners in a state of such collapse it was necessary to prop him up against a post, says Lokal Anzeiger of Berlin, which claims to have received from a high Russian personage an account of the Emperor’s last hours.

As he was unable to stand without support when the place of execution was reached, he was propped against a post. He raised his hands and seemed to try to speak but the rifles spoke first and he fell dead.

We know now, of course, the scene was far grislier than described above. The Czar and his entire family were herded into a small room and with few preliminaries met with a hail of gunfire from their executioners.

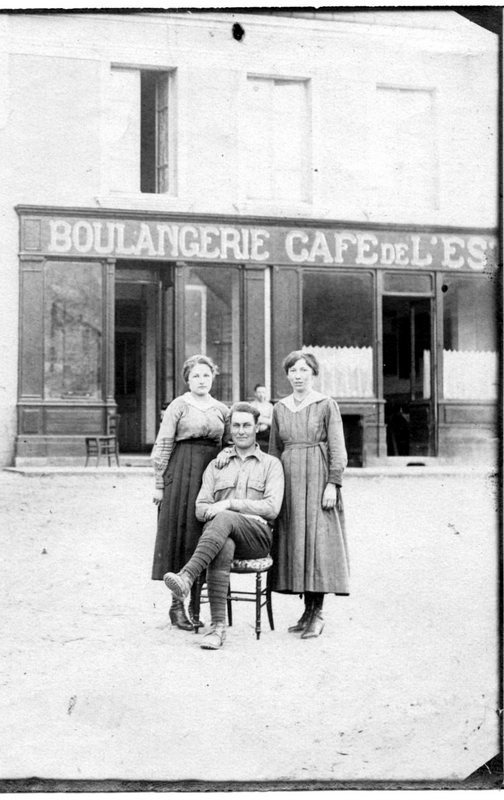

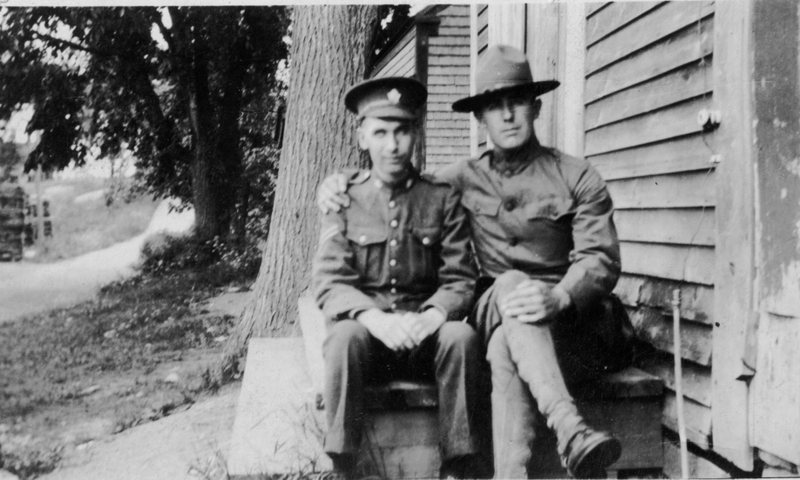

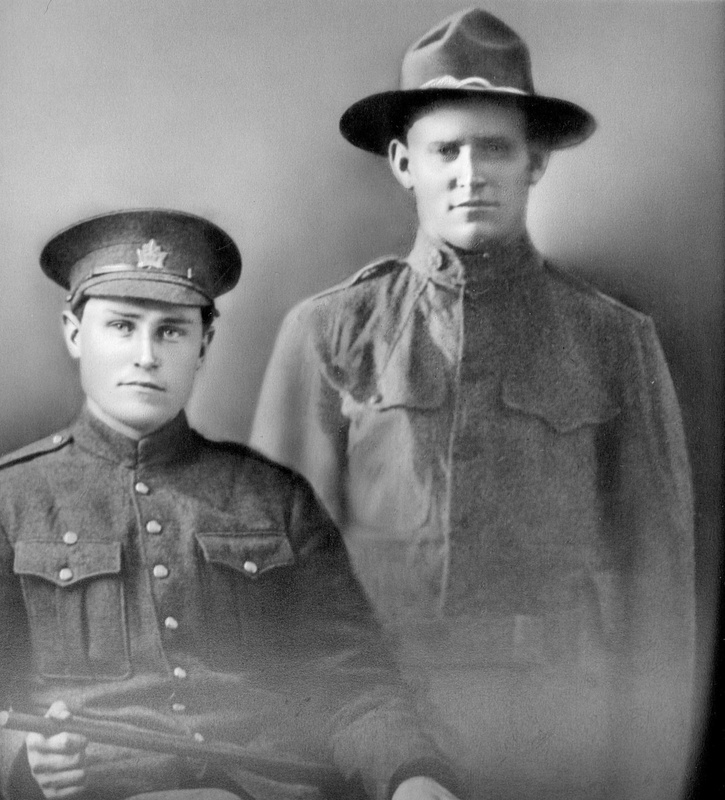

German General Ludendorff was elated of course by the fresh infusion of troops on the Western Front but remained despondent about the outcome of the war. The United States had been woefully unprepared to assist the Allies when it declared war on Germany in the spring of 1917 but America had quickly righted the ship. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers such as Charles Andrews of Baring, seated between the two ladies, and Frank Tyler on the right above of Calais had arrived in France as had untold numbers of trucks, tanks and artillery pieces. More were on the way. By March 1918 over 200 soldiers from Calais, 30 from Robbinston, and similar numbers from other towns in Washington County were either in France or on the way and, as noted above, far larger numbers of men from Charlotte County had been on the front line for years. Ludendorff knew he had only a brief window of opportunity to achieve victory or force a peace on terms acceptable to Germany before the Allies would overwhelm German forces. He decided to gamble all by going on the offensive while the odds where better than they would be in a few months when hundreds of thousands of additional “Yanks” would have arrived in France . Still he had to wait for the arrival of his forces from Russia and during this period of relative quiet in Europe life in the St. Croix Valley went on but with constant reminders that there was a “new normal”.

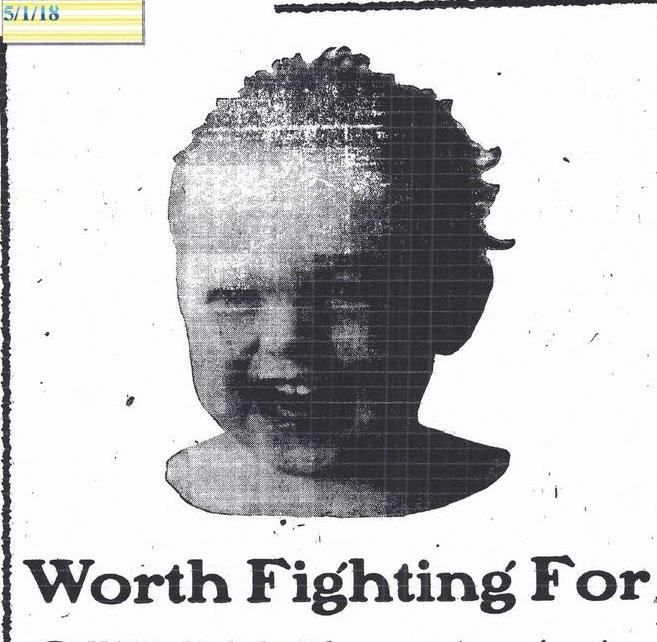

The Calais Advertiser and St. Croix Courier were for the most part still local papers although in 1918 much of the news was about the war including a good deal of war propaganda such as the above photo from the Advertiser which asked, “Will this little girl grow up healthy and happy in America or under the Thumb of the Kaiser?” In the event the reader was not certain of the correct answer to the question the Advertiser provided a hint in an ad for a film to be shown at the Calais Opera House described as “THE GREATEST EXPOSE OF THE KAISER AND HIS BAND OF LUST MADDENED HUNS”. The Advertiser asked if it were humanly possible for a true-blooded American to witness the film titled “THE KAISER, THE BEAST OF BERLIN” and not feel the blood boil. Only after putting everyone in the right frame of mind about the sacrifices which had to be made to defeat the Huns did the paper report the local news and it is somewhat surprising that daily activities seemed to proceed almost normally in a world which had, quite frankly, gone mad.

Local students continued their educations, and the last class graduated from the Milltown High School. Thereafter Milltown high schoolers attended Calais Academy, a decision which was not universally popular.

The St. Croix Valley suffered through a terrible winter in 1918, the river froze early and did not thaw until later than usual as even ice breakers were unable to force their way through. On January 30, 1918 the local fuel committee reported there was only a week’s supply of coal left in town and advised everyone “where it is possible to substitute wood for use in stoves and furnaces”. Loaded coal vessels were then waiting in New York and Lubec for favorable conditions to relieve the crisis. Streetcars had, at times, been abandoned on the tracks because of the depth of the snow which often required those boarding the cars to “step down” into the cars from the snowbanks above. Streets were blocked for weeks at a time and many horses injured their legs breaking through the thick crust on the snow. Calais had its share of fires in 1918 including one which severely damaged the Beckett Block on Main Street and not for the last time: the block was devastated by an even more serious blaze in 1937. Railroad accidents resulted in deaths, including a 10-year-old Milltown, N.B. boy who slipped trying to board a moving train and fell under its wheels and a train/car collision at the Baring crossing took the lives of an elderly couple. Almost all the ads in the papers suggesting buying from a particular merchant was patriotic. Lyford’s Clothing in Calais claimed buying one of its expensive wool suits was good for the war effort because they never wore out and hence would not need to be replaced during the war.

However, the war was never far from people’s minds and came very close to home in August 1918 when a German submarine sank the schooner Dornfontein off Grand Manan. According to a sailor on the Dornfontein:

“On Tuesday morning last we drifted out to sea from the port (St. John) and had a favorable wind at the start but later encountered bad weather. From Tuesday to Thursday the trip was uneventful but on Thursday morning about 11 o’clock we sighted a dark object to leeward. We had no idea of a submarine in the area and proceeded. A strange thing happened after this as a large black bird circled around the vessel and alighted on the after rail. A black bird at sea is regarded as a bad omen but we thought little of it.

As it happened the black bird was definitely a bad omen for the ‘black object’ surfaced with its guns trained on the Dornfontein. The captain of the sub advised the crew to come aboard and ‘be quick also’ an order with which the crew promptly complied. The crew was taken onto the submarine while the sub’s crew made 7 trips to the schooner to remove all the useful stores and on the last trip placed bombs and fuses in the gasoline tanks and on returning moved some distance from the Dornfontein. A loud explosion was heard, the Dornfontein lifted into the air, splinters flew, sheets of flame flared up, her masts collapsed and the vessel was but a mass of burning wreckage. After she sank, the sub’s crew gave the Dornfontein’s crew a good meal during which they were told the sub had “been patrolling off Eastport but as there was nothing stirring, they came up further until they encountered us.’ After apologizing for destroying their vessel the captain put the men in a boat ‘shook hands with us, wished us goodbye and good luck and gave us directions to shore.’”

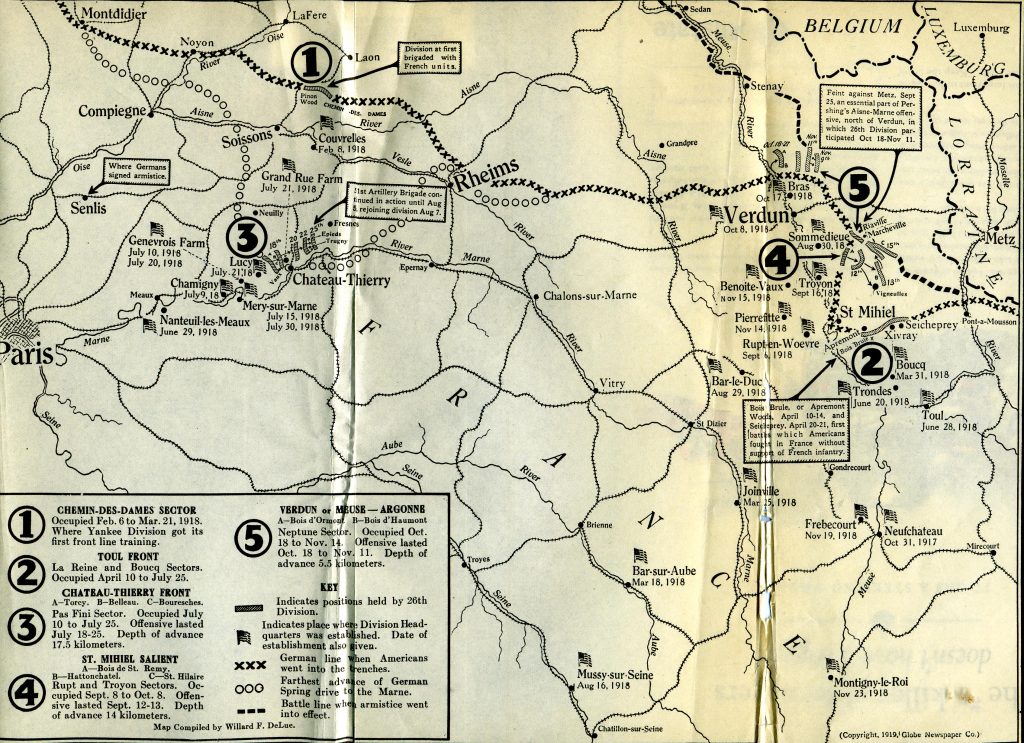

The sub’s mission was to keep supplies from the United States and Canada from reaching the Allies in Europe. The decisive battles of the war were being fought. Ludendorff’s last roll of the dice began with his spring offensive on the Somme and culminated in the Second Battle of the Marne in the summer of 1918. Men from both sides of the St. Croix River were to figure prominently in these battles, casualties—both dead and wounded—were reported in the local papers and for the first time these reports included the names of local men serving with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The papers also printed letters from local soldiers fighting at the front. Some of the casualties resulted from the Spanish Flu, such as Roy Therian of Milltown Maine who died at Fort Devens, just a few hundred miles from home. Most of the local men killed or wounded in action served in the 26 Division, nicknamed the Yankee Division, several in Company I of the 103rd Infantry. Others, such as Joseph Polis of Pleasant Point had enlisted earlier in the Canadian Army. From the Calais Advertiser, October 2, 1918:

Private Joseph Polis of the Passamaquoddy Tribe of Indians of Pleasant Point reservation, was fatally shot in the head last month and died recently at a hospital in Boulogue. He was aged 27 years, unmarried, has a mother and grandmother at the Indian village, his father having died some years ago. Private Polis enlisted in the Canadian Army in the Kilties regiment, also has two brothers, Frank and John, from the Passamaquoddies who enlisted with the Canadian Army. He is the third member of the tribe to be killed in action.

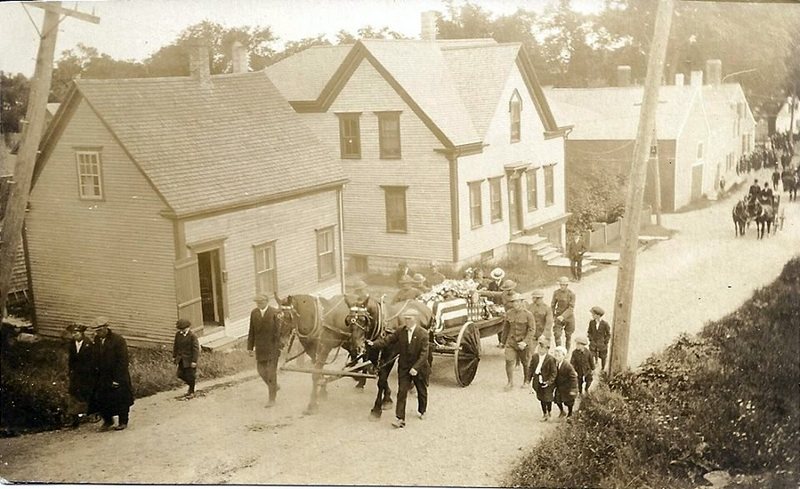

The photo above shows a military coffin proceeding up Fort Hill to the cemetery in Eastport in 1918. We do not know the identity of the soldier but the Eastport Sentinel often had to report unwelcome news from the front as did the Advertiser, which reported on August 21, 1918 about an Eastport boy as follows:

A letter received Saturday from Private Elmer Griffin, Company I, 103rd U.S. Infantry, 26th Division, now in France, states he lost a leg above the knee while in action and has been gassed. He is expected to arrive in Eastport within a month.

Also in Company I of the 103rd Division were Fred and Harry Sherman, brothers from Calais who enlisted in 1917. They were among the first American troops to see action in France, fighting for the first time as an independent American unit without French assistance.

On April 20, 1918, the Germans attempted to break the Allied lines at Seicheprey. (#2 on the map above). The 103rd, defending the sector, acquitted itself well and drove the Germans back. However, by June German General Ludendorff knew it was do or die for his German armies, and he again launched even heavier attacks against the position held by the 103rd Infantry. On June 16, 1918, the Germans overran the positions held by the 103rd at Xivray, killing Fred Sherman and Earl Severance of Topsfield. In fierce fighting, the Germans were once again driven back and the line stabilized. Fred’s brother Harry had no time to grieve his brother. The Germans also attacked with even heavier forces at Chateau-Thierry (#3 on map), and the early success of this attack threatened Paris. The 103rd Division and other elements of the Yankee Division, together with the 1st and 2nd U.S. Divisions were rushed into the breach where they gained the everlasting gratitude of the French nation and the moniker “The Saviors of Paris” for stopping the German onslaught. Harry Sherman died at Epieds, France July 22, 1918, retaking the road to Soissons, cutting off a major German supply line. It was not until September of 1921 that the bodies of the Sherman brothers were returned to Calais and, after a moving and emotional funeral at the Baptist Church, buried in the Calais Cemetery.

As we know, the war went on for another three months and casualties continued to be reported in the local papers. Albert Mercier of Princeton fell in October of 1918 in combat and the Spanish Flu continued to take lives. Nonetheless, the 1918 battles in which the 103rd distinguished itself marked the beginning of the end for the German Army. When the war ended in November, joy was tempered with sorrow here in the St Croix Valley, especially on the Canadian side. St. Stephen alone had lost 87 of its finest young men.

In the St Croix Valley, only two war memorials survive although many were erected especially after the Second World War. The one seen above is on the left just after crossing the bridge at the Park on Milltown Boulevard in St. Stephen. The second is Calais’ striking Civil War monument at Memorial Park. It is no doubt a function of the fearsome losses in the two the communities—St. Stephen in the Great War and Calais in the Civil War—that care is taken to maintain them. The war memorial in St. Stephen was erected in 1926 to memorialize the sacrifice of its soldiers in a war that finally ended on November 11 at 11:00 P.M. 1918—the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in the railroad car at Compiègne, France.