When the United States entered World War 2 in December 1941 one issue which didn’t require much war planning was where to house prisoners of war. The Allies were on the back foot in every theater of operations and both the Germans and Japanese were on the offensive. It wasn’t until the campaign in northern Africa in 1942-1943 that the Allies achieved any significant victories. At El Alamein and later Tunisia British and American troops were victorious in several major battles and captured large numbers of German soldiers who had to be interned until the conclusion of the war. British Tommies are seen above capturing and leading some of the Germans away from the front.

Remarkably, these victories were over armies led by Erwin Rommel, Germany’s most capable general although in his defense the outcome would possibly have been different, especially at El Alamein, had Rommel not literally run out of gas. As it was German armies were forced to retreat and in 1943 abandon North Africa altogether leaving behind 134,000 soldiers who became prisoners of war. Most of these were sent to about 500 POW camps in the United States. One of these camps was in Princeton on Indian Township. From the Calais Advertiser, January 26, 1944.

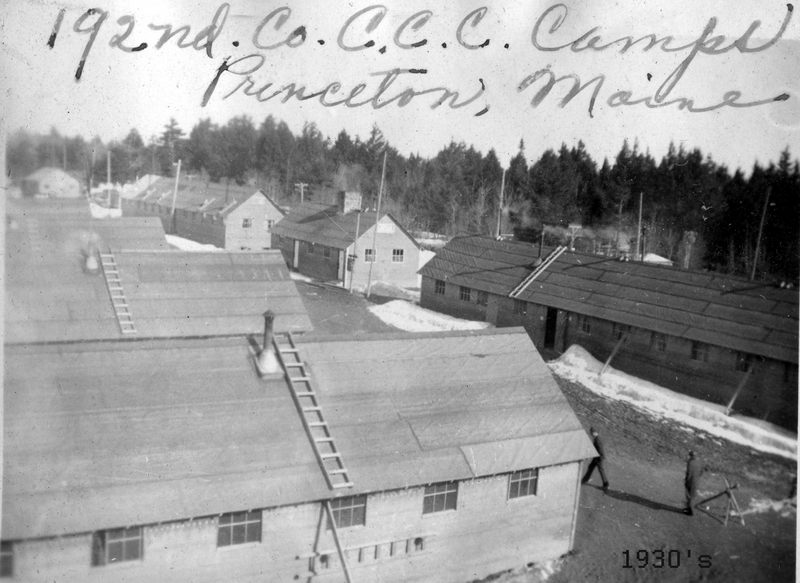

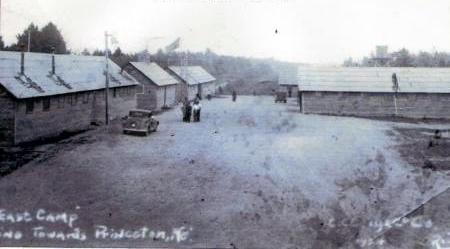

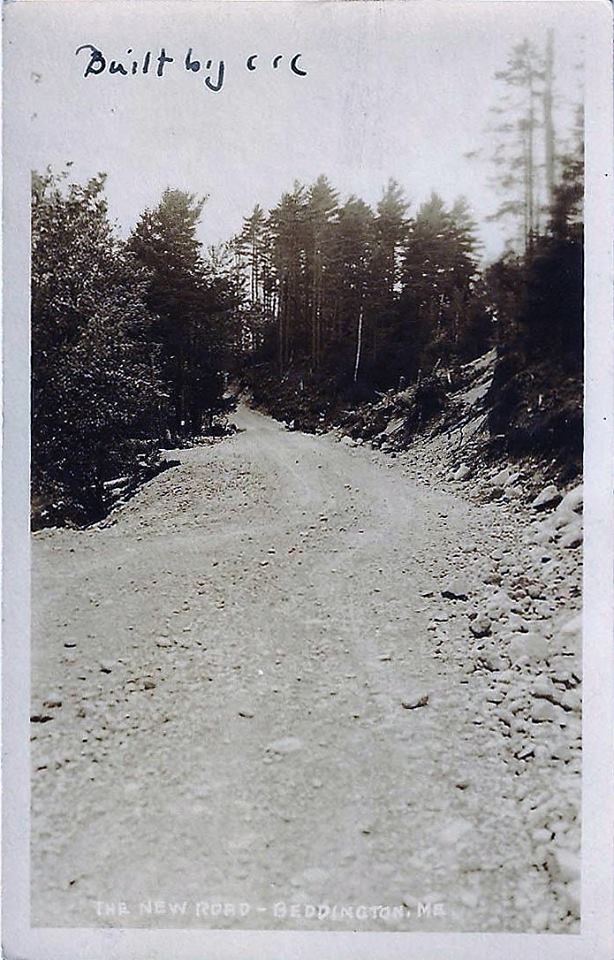

The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) camps had been built during the Great Depression, the Princeton camp in 1933 on Indian Township north of the bridge on what we now know as the “Strip”. Roosevelt established the CCC Camps and WPA (Works Progress Administration) to provide jobs for the millions of unemployed Americans. Men from Washington and Aroostook counties, including the writer’s potato farmer father from Washburn, lived at and worked out of the camp through the thirties until the Army found employment for nearly all of them after December 7, 1941.

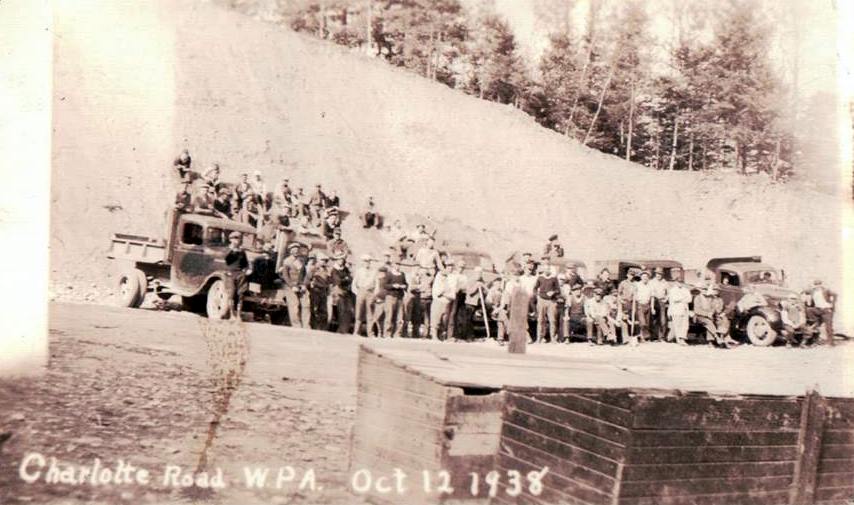

The men worked mainly on construction projects in the area such as the Charlotte Road in 1938.

Men from the camp also did a good deal of work on the Airline. However, by the early ‘40s they were all in uniform, and road building had ceased as, to a large extent, had farming and woods operations because of a shortage of labor. This had a dramatic effect on the national and local economies as wood products were essential to the war effort and food was essential to everyone. The paper companies were especially desperate for workers and managed to convince Washington to allocate some of the prisoners of war then in the United States to Northern Maine. There was opposition, first from the cotton industry in the South which had many of the POWs working in the cotton fields but also from some politicians who disagreed with the idea that POWs should do other than be confined to camps under, ideally, miserable conditions. Coddling “Nazis” was, not surprisingly, unpopular. The government pointed out that the United States was a signatory to the Geneva Conventions and further that thousands of U.S. troops were in German POW camps being generally treated better than other captured Allied soldiers because of the fair treatment their soldiers were receiving in the states. The abandoned CCC camp in Township was considered an ideal location for a POW camp, and after renovations and proper security arrangements were completed the first prisoners arrived. According to Jocelyn Curtis who has written the definitive history of the Princeton POW camp:

There is some difference of opinion about when the first German POWs arrived at the Princeton camp, but according to Donald Soctomah, the Passamaquoddy historian, the first arrival was on May 9, 1944. At 8:00 in the morning on the 9th a train drawn by 2 engines arrived in Woodland, Maine with about 286 German prisoners ranging between the ages of 14 to 23 with 30 armed guards in charge of them. The majority of the Germans that stayed in the Princeton camps were from Rommel’s Afrika Korps or were U-boat men. Before coming to Maine, some of the POWs were picking cotton in Louisiana. The majority, though. came directly from overseas by boat to Boston. They were then transferred by railroad to their Maine camp. For many of these prisoners though coming to the wooded areas of Maine was like coming to the end of the world and that they were in a place nowhere near anything in their experiences.

Above is a rare photograph of prisoners at the camp in Princeton. Taking photographs of the camps, its prisoners or the guards was strictly verboten and few photos survive. The locals were somewhat ambivalent about their new neighbors-some were, in the beginning, overtly hostile but most were simply curious. Again, according to Jocelyn Curtis:

Harriet Martel, who was an 8th grader in 1944 remembers the day the POWs were unloaded off the train in Woodland. Her teacher took all the students out of class to watch the POWs first come into the train station. The class stood by a garage in front of the train tracks as the train came in. The guards would not let the townspeople who had gathered to watch the event onto the tracks, but Harriet remembers seeing the POWs waving and saluting as they came off the train. Harriet felt more curious than scared and waited for the last POW to come off the train before she was escorted back to class. From many reports the POWs seemed joyful as they got off the train and that the only really tough looking person was a top sergeant of the guards. Harold Glidden of Princeton said that the Germans were nice, rugged guys that were mostly blonde and very tan. Once off the train the guards did roll-call and then put the POWs in trucks to be driven to Princeton.

Before the POWs arrived in Princeton, the townspeople were informed that the POWs would be coming into town. They were first told that the majority of the POWs were Czechs but were later informed that the men would be Germans. When the first trucks with POWs came in all the Princeton residents stood outside their houses and watched them come down Main Street. Louise Deschene, who lived on Main Street in Princeton, became nervous when the trucks passed her house and she heard the German POWs singing German songs and shouting to the people. Louise even thought they were yelling ·’Heil Hitler.’ which made her very scared. She remembers that the POWs were let out of the trucks in the main part of town and were made to march from Princeton across the bridge to the Indian Township and to the camp. Louise thought the guards did that so that the townspeople could have a better look at the prisoners.

The POWs had no conception of the type of work that lay ahead of them or the extreme winter conditions in which they were to work. There were no chainsaws in those days and a woodcutter had to be pretty hardy and handy with an axe or crosscut saw which was not the case with soldiers from Rommel’s army. The Maine woodsmen pictured above could take down a forest before noon, it was to take the POWs a good deal longer. While the men at the Princeton camp were to be engaged exclusively in harvesting wood, others, such as those at a similar camp in Houlton, generally worked in the potato fields. The POWs’ day began at 5 AM with lights out at 9 PM. They were loaded on trucks driven by men from Princeton at 6 AM and taken to the woods—often at Grand Lake Stream—where a paper company foreman met them, issued them axes and other tools of the trade, and took them to their work area. Guards accompanied the POWs, but in the winter it appears the guards took advantage of the heated guard huts and allowed the POWs a good deal of freedom so long as they each cut 8/10ths of a cord of wood a day, the minimum requirement. As the foremen and guards became more familiar with the POWs, they allowed them, on particularly frigid days, to share the stove in the guard hut. The increasing fraternization between the guards, paper company supervisors and POWs was seized upon by some politicians who had always resisted the “work camp” setting as they claimed the POWs weren’t productive workers and were allowed a measure of freedom not consistent with their status as “prisoners of war”. Some townspeople felt likewise and complained that the POWs had life easier than they did and ate a lot better too. These complaints compelled the government to allow a reporter, Oscar Shepard, to visit the camp, talk with the guards and officers and report on the situation in the Princeton camp. Shepard submitted a lengthy article to the newspapers quoted in part below:

In The Maine Woods · News Writer Inspects Their Camp

By OSCAR SHEPARD

Several hundred German prisoners of war—the exact number is not disclosed—are working as lumbermen in the Maine woods. They fill the places, in some degree, of Canadian woodsmen who no longer cross the border-line and of native Americans who have been absorbed into war industry and the armed forces. Their labors, it is hoped, will improve the pulpwood situation, admittedly more serious than it has ever been in Maine. A unique experiment, undertaken with courage and high hope.

How are the survivors of Rommel’s once Grand Army in the African campaign—mostly from places like Frankfort, Blenheim, Mannheim and Darmstadt in Middle Germany—getting on? Are they adaptable? Are they willing workers? What practical value, measured in dollars and cents and feet of cut Lumber, has their labor been? Are they troublemakers? Do they seem appreciative of the kindly and humane treatment accorded them or do they show a hatred of America?

Naturally enough, there have been confused, contradictory and disquieting reports. “I believe,” a Washington statesman wrote the Bangor Daily News, “that a comprehensive story would do much to correct misunderstanding and relieve confusion through Eastern and Northern Maine”. As the first Maine newspaper man to visit one of these internment camps, the writer has tried very hard to get an accurate picture.

For dinner, on the writer’s arrival, there was a thick lamb stew, which included peas, celery, tomatoes, potato and lima beans; cabbage salad, stewed pineapple, peanut butter, marmalade, bread and coffee with evaporated milk. Most of it came from Dow Field in Bangor, and it was as good as could be found in the average restaurant or hotel.

The prisoners have their own mess, their own cooks, and exactly the same food, an officer explained. The same basic materials, I mean, and in the same amount. They can cook and serve these materials in any way they please. But they eat just what is given our enlisted men.

Are these prisoners coddled or pampered? Those in charge say definitely not. One officer said: The United States is adhering strictly to the letter and the spirit of the Geneva Convention as a matter of national honor and integrity. Accordingly, prisoners are treated humanely, as soldiers of an opposing Army, and not as criminals. However, strict discipline is maintained and in no instance are they pampered. This treatment may be characterized as fair but firm.

To summarize: there is no friction in this Maine experiment; both Americans and Germans have been honest in their efforts to avoid it. Camp routine goes smoothly. Residents of the vicinity, if ever they are apprehensive, are no longer so. The prisoners have shown no unwillingness. Production figures are unavailable, as has been said, for supervisors think results satisfactory, remembering always these men have no background as woodsmen and have been in the woods only a month.

The experiment hasn’t completely proved itself, but it’s progressing in a way that gives encouragement to those who planned it. It seems well worth encouraging.

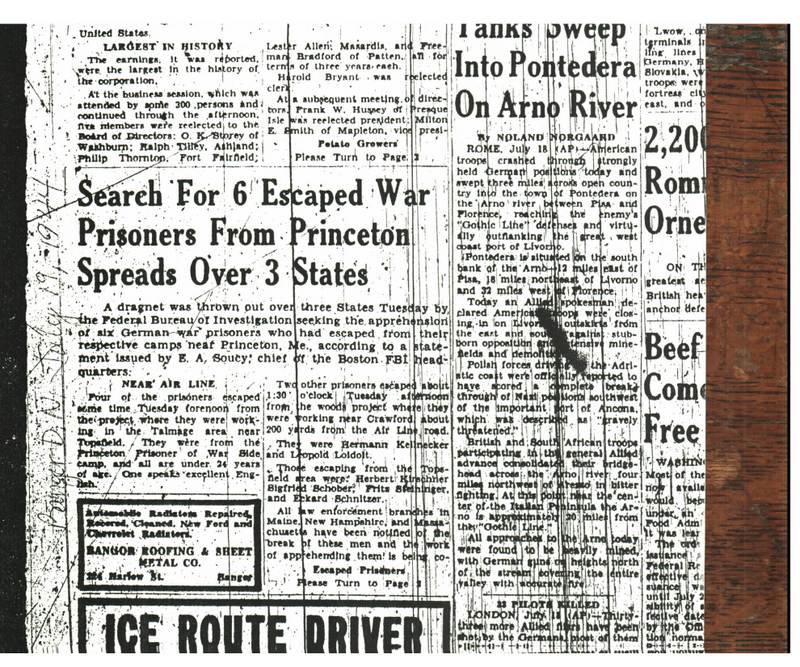

From Bangor Daily News, July 19, 1944:

Search for 6 Escaped War Prisoners From

Princeton Spreads Over 3 States

” A dragnet was thrown out over three States Tuesday by the Federal Bureau of Investigation seeking the apprehension of six German war prisoners who had escaped from their respective camps near Princeton, Me., according to a statement issued by E. A. Soucy, chief of the Boston FBI headquarters.

Four of the prisoners escaped Tuesday forenoon from the projects where they were working in the Talmage area near Topsfield. They were from the Princeton Prisoner of War . . . camp and all are under 24 years of age. One speaks excellent English. Two other prisoners escaped about 1:30 o’clock Tuesday afternoon from the woods project near Crawford about 200 yards from the Air Line road. They were Hermann Kellnecker and Leopold Loddort.

Those escaping from the Topsfield area were: Herbert Kirshner, Sigfried Schober, Fritz Sheninger, and Eckard Schnitzer.

All law enforcement branches in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts have been notified of the break of these men and the work of apprehending them is being carried out by the FBI.” (A complete description of the men followed.)

It is the sworn duty of soldiers of every army if taken prisoner to escape and rejoin the fight, so it should not be surprising that a number of escape attempts were made by Princeton POWs. Most naturally occurred while the men were working in the woods and involved simply walking off into the forest with no real plan in mind. Like the men in the Bangor Daily News article above they were soon captured. A few fellows of the six above did put some distance between themselves and the camp, four made it as far as Enfield where game wardens apprehended them but getting that far was unusual. Most escapes were of a more comic variety: Dale Brown recalls two such escapes:

U.S. Highway #1, a not-so-heavily-traveled road passed along the east boundary of the camp and traversed sparsely populated areas to the north and south. On one occasion. two prisoners escaped and managed to reach a point on the highway south of the camp halfway between Princeton and Woodland without being seen. Their destination was Canada’s New Brunswick coast where they had been told it might be possible to make contact with a German submarine and be rescued. However, they were tired–so they decided to take a chance on hitchhiking. They had found the locals to be friendly on the rare occasions they had contact with any of them, so they believed there would be no threat to their new-found freedom. Returning from a court trial in Danforth several miles north of the camp, the Washington County Sheriff was the first motorist to whom they extended their thumbs! He, of course, noting the P.O.W. lettering on their shirts, stopped for them. When they were in the car, he showed them his badge, made a U-tum and took them back to the camp…. all without incident.

Six miles south of Princeton, and seven miles on a dirt road east of Route #1, in the small community of Kellyland, on the west bank of the St. Croix River, and the Canadian border, a lady received a visit from two escapees. Mrs. Francis Abbott had just finished baking several blueberry pies when she heard a knock on her back door. Upon opening the door, she was confronted by two tired, sweaty, young men in P.O.W. garb who, in halting English made her understand that they were hungry and thirsty. Her heart pounding with fear, she invited them to sit down at the kitchen table, where she served them generous slabs of blueberry pie and large tumblers of cold milk. When they were finished, and meaning her no harm, they thanked her and asked the way to the river (which was only a few hundred yards from the house). She told them and they thanked her again, then ran into the woods toward the border. When Mrs. Abbott was satisfied that they were gone, she made a quick call on her crank-type telephone to her husband, at work in the hydroelectric plant nearby, and related her experience. A telephone at the plant was the only one in the community with which it was possible to contact the outside world, and Mr. Abbott used it to call the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The Mounties immediately launched a massive search and, just before midnight, and meeting no resistance, captured the escapees, who had been hiding in the woods not too far from where they had crossed the river. Once again, justice had prevailed, and the two young soldiers were returned to the P.O.W. camp.

No one successfully escaped from the Princeton camp. One rather more serious attempt was thwarted by the prisoners themselves. While on lunch break deep in the woods at Grand Lake Stream a hard-core Nazi and his friend decided it would be a good day to rejoin the fight. Dusty Brown of Grand Lake Stream relates his father Lewis Brown’s description of the incident:

“It was a warm March day, and the men were all sitting around a fire. Germans jumped up on a stump and began to harangue the prisoners in German. Dad asked “Superman” what they were saying because one of the few words of German Dad understood and was being repeated was “RAUS” which meant hurry. Superman replied “He very foolish, he want to escape.” Lewis told him to tell the other German he was free to go. The man’s expression conveyed that he didn’t believe it. This German had a companion who was always with him, so when the noon hour ended, and they were preparing to go back to work, these two jumped on the guard and were taking his gun when the rest of the prisoners realized what was going on.” “It was at that point,” Lewis said, “that the whole thing took on the aspect of a Laurel and Hardy movie. Germans began leaping on the two escapees until they were all in one big pile on the ground. fists flying. After a long while, 3 or 4 minutes, Lewis said. “the prisoners got up, helped the guard up, brushed him off, and handed him back his gun. Four prisoners then kept the escapees in control with both arms twisted up behind their backs.” One of the prisoners then told Lewis that these men had been trying to get the prisoners to revolt for 2 or 3 months. He said, “those men. S.S. bad men. We have good food, good beds, warm place to sleep, good work, good friends (meaning Americans) better than Germany. Those men stupid.” The prisoners then tied these two battered Germans up with their own shoelaces and put them on the bus for the rest of the day. The two were shipped somewhere else and never seen again.

There are some rather vague accounts of prisoners being shot while trying to escape from the camp but there is no record of any such occurrence.

More common was the experience of Virgil Schrader, a tower guard, who recalls taking prisoners to Lewey’s Lake for a swim on hot days, and it is not disputed that close relationships were established between some locals and the POWs. The locals were sometimes given butter and meat by the prisoners which were hard to come by on the local economy but were supplied to the POW camp under the Geneva convention which required POWs have the same rations as U.S. Army enlisted men. This arrangement would not have done much good to Americans held in German POW camps at the end of the war as rations to German soldiers were continually reduced as the Germans lost territory. Many of the POWs took courses in English through the University of Maine and became quite fluent so were able to communicate with the guards and local contractors on a personal level.

The POWs became fluent in another language with their nearest neighbors, the Passamaquoddy who had a certain amount of sympathy for the POW’s plight, having been mistreated by the white man since his arrival on the continent. Again, we’ll let Jocelyn Curtis tell this very interesting story:

This sympathy turned into physical attraction for some Passamaquoddy women. Some German prisoners found that they could “escape” under the fence or found they could make an agreement with the guard to go outside the camp. They would go across a path to the Indian Township and have sexual relations with some Passamaquoddy women. The Germans would return to the camp the next morning across the same path. This “path” was used so often by the Germans that townspeople started to call it the love path. There is at least one report of a child being born between a German man and a Passamaquoddy woman, but there were more rumors that there were other children born through this union and also unions between Germans and white women. The known case of a half German-half Passamaquoddy child became famous during the 1980s when the child’s German father returned to America.

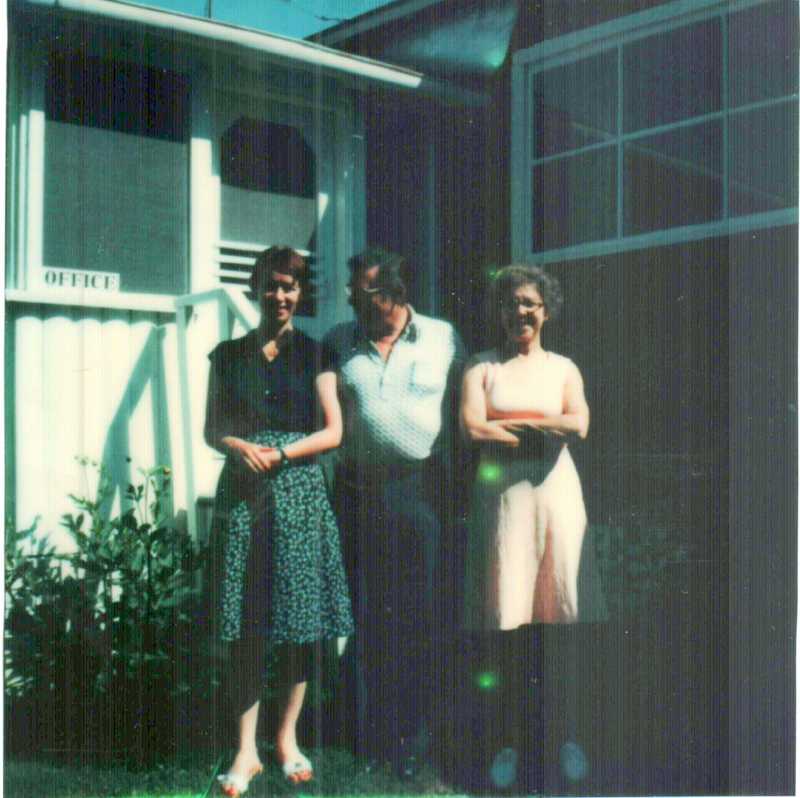

Wolfgang Ritter, standing above between the two ladies in Princeton in 1980, was a 23-year-old 1st lieutenant in the German army when he was wounded on the Tunisia front and captured by Allied forces. He was sent to America as a prisoner of war and ended up at the Princeton camp. He said that Princeton was a beautiful place and even though he was a prisoner he enjoyed his time there. While a prisoner at Princeton, Ritter met a Passamaquoddy woman named Mary Gabriel through the POWs’ camp fence. He told her that he was Polish so she would not be scared of him. When Ritter was able to sneak past the guards and meet Mary in the woods, he told her the truth that he was German; Mary did not seem to mind. Their relationship continued and Ritter slipped out of the camp several times following the “love path” to the reservation to meet Mary. Mary started calling Ritter “Molsam” which is wolf in Passamaquoddy to match his first name. During their relationship, Ritter even helped the Passamaquoddy tribe by helping Mary figure out legal papers that she had which said the American government owed the tribe money. Ritter got Mary to start the process to get the money back.

After being in Princeton and having a relationship with Mary for two months, Ritter and other officers were sent to Oklahoma because pro-Nazi pamphlets were being passed around the Princeton camp. Ritter left before Mary could tell him that she was pregnant with his child. Ritter was sent to Oklahoma and Texas to pick cotton. He escaped and worked under an Irish name in Illinois. Ritter was recaptured and was sent to Belgium with American troops to be used as an interpreter but escaped again and headed back to Germany.

In 1980, Wolfgang Ritter returned to Princeton from Germany to visit the old camp. A party was held by the people of Princeton in Wolfgang’s honor. During this party a man named Roger Gabriel came to Ritter and told him that he was his father. Roger Gabriel was the son Ritter never knew he had. Before that party, Gabriel was told by his mother, Mary, that his father had been a German prisoner of war who was held at the Princeton camp in 1944. Gabriel spent years looking for his father and it was only by chance that Ritter returned to Princeton by his own will. Ritter was overwhelmed when he found that he had a son, but later when they had their official meeting, Ritter was overjoyed. Roger told Ritter that he was a tribal planner on the Passamaquoddy reservation and was married with children. Ritter told Roger about his two half-brothers and invited him to come visit in Germany. After their meeting. Roger and Wolfgang legalized their relationship and Roger adopted his father’s last name. Once Wolfgang returned to Germany, the father and son relationship continued up until Wolfgang’s death. The Germans even helped the Passamaquoddy tribe by bringing four Native Americans to Germany to complete a program after noticing a high alcoholism rate on Indian Township. Wolfgang and Roger worked with the Passamaquoddy health director and earned $40,000 to bring the Native Americans to Germany. This experience of a man in a prisoner of war camp affected a culture and a new generation for years afterward.

Whether there were other liaisons between locals and the POWs is not known. It is possible, as many young women from Princeton described the physical appearance of the German POWs in glowing terms and exhibited a good deal of curiosity about the POWs. One young woman said she was not at all afraid of the Germans, and the women in town noticed they were “good looking boys” and fascinating and another who attended dances for the staff at the camp said she was not nervous around them and that they were “good-looking young men”. However, some of the men were heard to remark that the POWs ‘lived like kings”.

The camp did not close immediately after the war. Because conditions in Germany were very dire it was 1946 before all of the soldiers had been repatriated. Many maintained contact with their former guards and foremen and some asked for letters of recommendation to assist in request to emigrate to the U.S. Others like Wolfgang Ritter returned to visit although we are reasonably sure his visit was more memorable than any other.