According to John Howe of Cooper, the Calais Academy class of “45” was known as the “hard luck” class. There was, of course, the war and the tragedy of June 1944 haunting the class, and when commencement was held at the State Theater on June 7, 1945 the class was also without a school, Calais Academy having literally burned down around them on February 3rd, 1945.

Known affectionately as the “Old School on the Hill” the Academy was built in 1856 by the noted Calais architect Asher Bassford and was much beloved by the community. The origin of the fire was never determined but that it was purely accidental there was no doubt. An attempt to extinguish the fire by the principal and students was unsuccessful and it spread so quickly that when the fire department arrived from a block away it was already out of control. Groups of boys ran in and out of the burning building salvaging valuable equipment, including all 22 of the typewriters from the Commercial Room. The boys also managed to save all the school records—which was less important for some than to others. The only casualty according to the Advertiser was Paul “Porky” Boardman, a student knocked out cold, we thought, in a collision with another salvager, but Larry Lane’s personal account tells a different story.

Former student Larry Lane reports: “I was right there in the school when the fire started. As I remember, the fire started upstairs in the back of the building near the typewriting area. I was, at that time, in the downstairs east outside room with Miss Bates. We were waiting for the bell to ring so we were to go upstairs for the meeting in the big room up there. When the bell rang, Miss Bates said, ‘OK, it’s time,’ but then she exclaimed, ‘NO, it’s not that; that is a fire signal!’ and she took us out the door onto the grass on the east side.

“We were there on the outside, when she exclaimed, ‘Oh my, my fur coat is still inside there!’ Porky Boardman said, ‘I’ll go get it.’ She said ‘NO, don’t do that,’ but he was already on the run into the room. He came back out with the fur coat, and someone threw a chair out an upstairs window, and it hit him on the head.

“I had to attend school classes in the new school building near there and the South Street School. We had to walk all the way from the school classes at the gym next door to the burned academy, down to the old South Street School. That was then still there. The only bathroom there was down in the cellar. I remember going down there to do my business, and seeing a message there that said, ‘Do not piss on the floor, the janitor cannot swim.’”

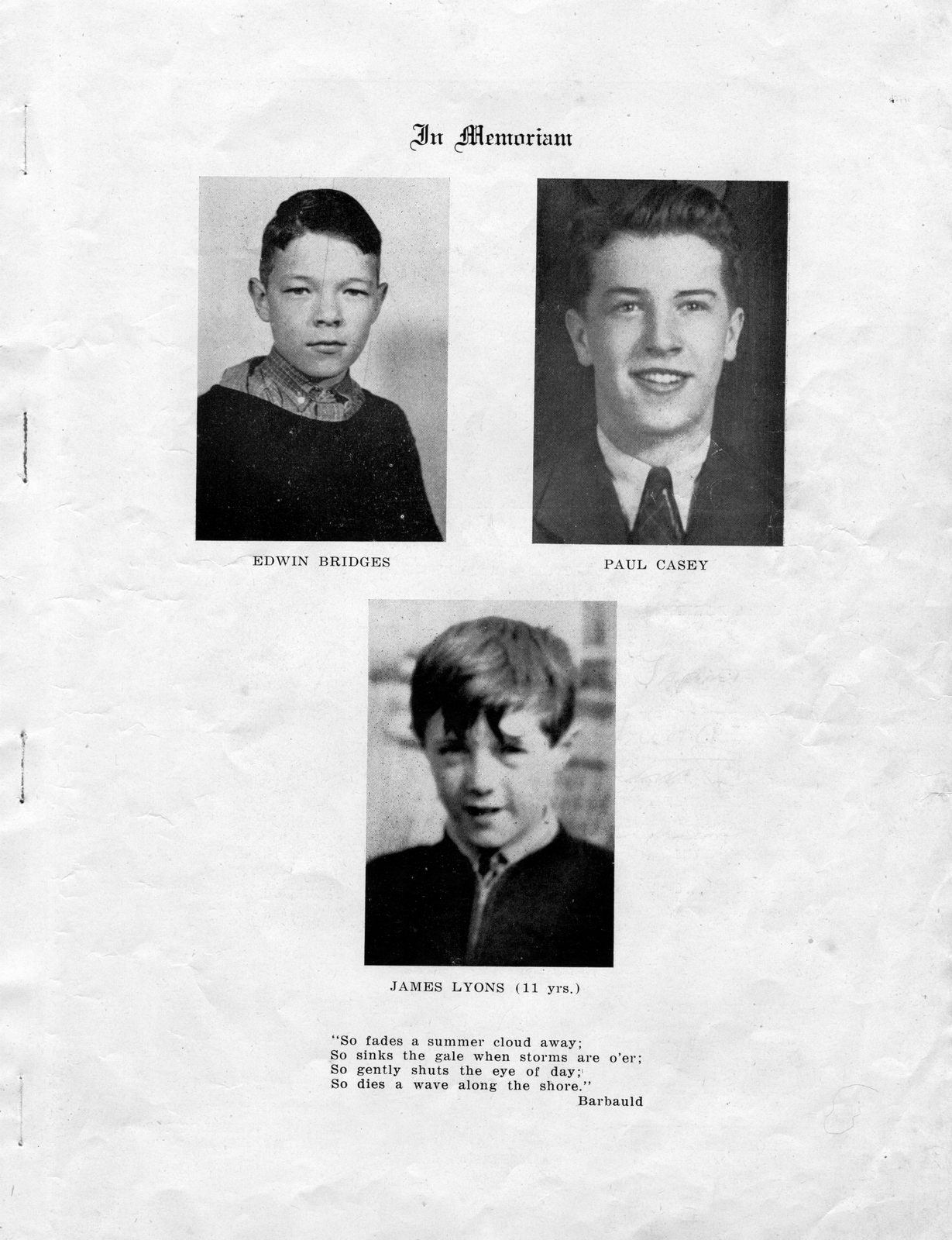

“So fades a summer cloud away;

So sinks the gale when storms are o’er;

So gently shuts the eye of day;

So dies a wave along the shore.”

— Anna Letitia Barbauld

Many of their classmates were already at war; one had recently been killed in action in Europe and three had died under tragic circumstances—two at the junior class picnic at Cathance Lake the previous summer. An “In Memoriam” 1945 yearbook photo shows three classmates, Edwin Bridges, Paul Casey and James Lyons. James was accidentally shot by his brother in a hunting accident in November of 1944. Eddie Bridges drowned in Cathance Lake trying to save his friend and classmate Paul Casey on June 5, 1944.

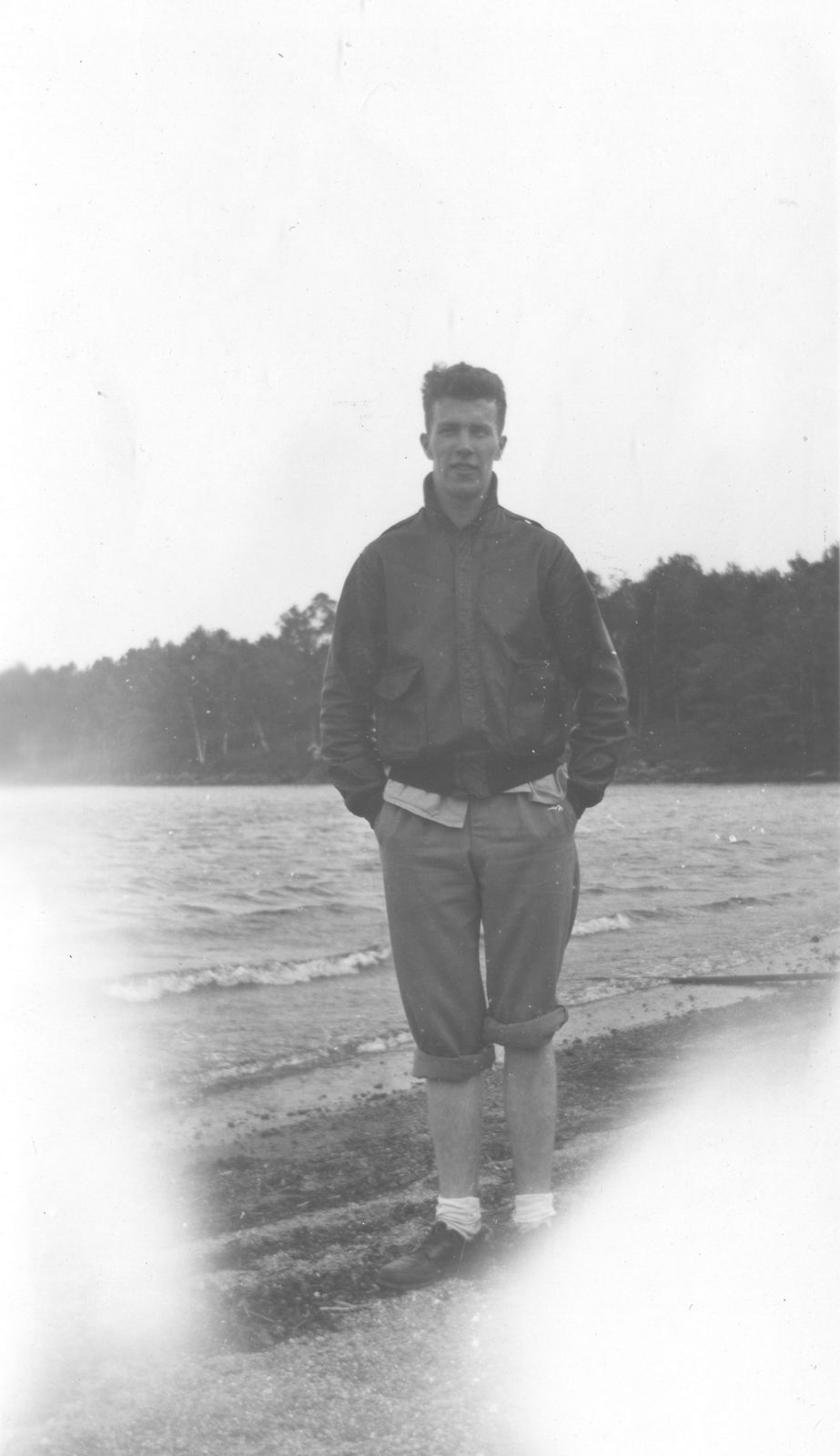

In those days it was traditional to have an end of school picnic, and the junior class arranged to use Pete Peterson’s cottage on Cathance Lake. Pete owned the Chevrolet Garage on Main St. and his daughter Norma was a member of the class. John Howe, who lived near the cottage, recalls driving the farm truck to Calais the morning of June 5, 1944 to pick up about 15 of his classmates. The rest arrived with teachers and friends. John believes nearly the entire class was at the picnic. A classmate snapped the above photo of Paul Casey wearing a flight jacket on the beach during the picnic; he’d obviously been wading in the lake but not swimming. Paul couldn’t swim a stroke. When the chaperones announced it was time to leave and John Howe had loaded his classmates in the back of his truck to return to town, he noticed Paul Casey and Edwin Bridges in the canoe, very near shore but thought nothing of it. Jean Doncaster, whose father ran Calais Box and Lumber Co., joined Paul and Eddie in the canoe and by the time they were noticed by one of the teachers, the three had paddled about 200 feet from shore. They were told to return immediately but according to Peter Delmonaco neither boy knew how to handle a canoe and when they tried to turn quickly, the canoe came broadside to the wind. To the horror of those on shore, the canoe flipped and all three were dumped into the lake. None were wearing life jackets or managed to hold onto the canoe and there was chaos on the beach as classmates were screaming and crying helplessly watching the three struggling in the water. Peter Delmonaco and Roy Gillis raced to the locked boathouse and, while they couldn’t open the doors, they managed to swim through the gap between the doors and lake. Inside was an old rowboat which the boys somehow dragged under the doors and into the lake. They had only one paddle and almost no experience handing a boat but they doggedly tried to reach their friends, handing the paddle back and forth and, according to Peter, zigzagging toward their classmates. Sadly only Jean Doncaster was afloat when they finally headed out into the lake. In the time it had taken them to get the rowboat, Eddie Bridges, a strong swimmer, had gone to aid of his good friend Paul and in a valiant effort to keep Paul from drowning, had been dragged under by Paul in full view of dozens of their classmates watching from the beach. Jean was able to swim a bit and was aided by a jacket which ballooned when she went into the water. When Peter and Roy reached her, she was hysterical and the boys had a very hard time getting her into the boat which was nearly capsized in the rescue effort. They then searched for Paul and Eddie but to no avail.

There was no investigation or recriminations and only one article in the Advertiser about the tragedy. This may have had to do with the historical context. At the very moment the boys launched the canoe into Cathance Lake, the first landing craft were lowered into the English Channel to assault the beaches of Normandy. Within hours of the tragedy and for days following, tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers would pour onto the beaches in France, including Brand Livingstone and many soldiers from Calais. Thousands would die and many would suffer the same fate as Paul Casey and Eddie Bridges in the surf of the Normandy beaches. None were any braver, however, than a Calais Academy junior, Edwin Bridges, who gave his life in an attempt to save his friend, Paul Casey.

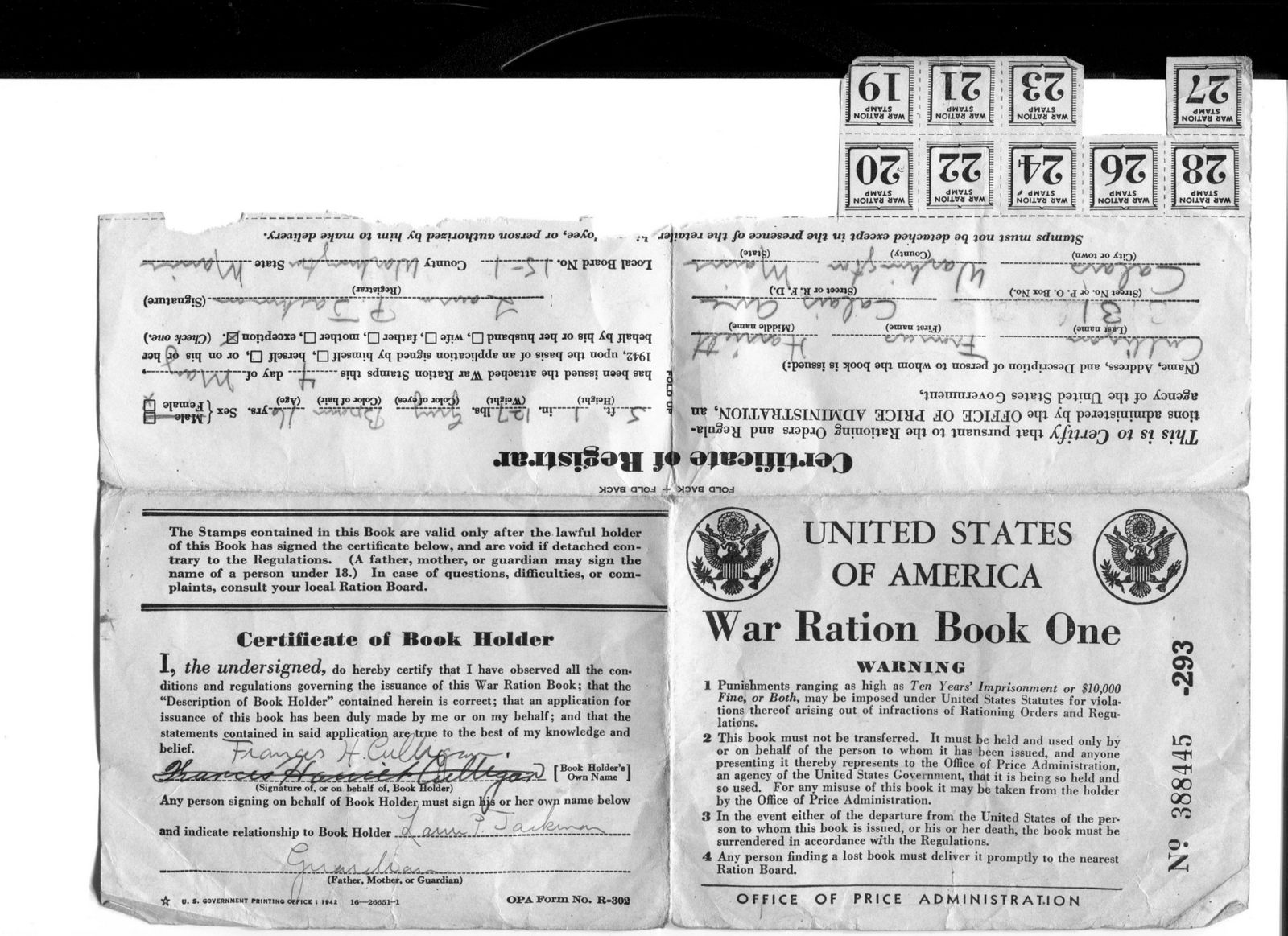

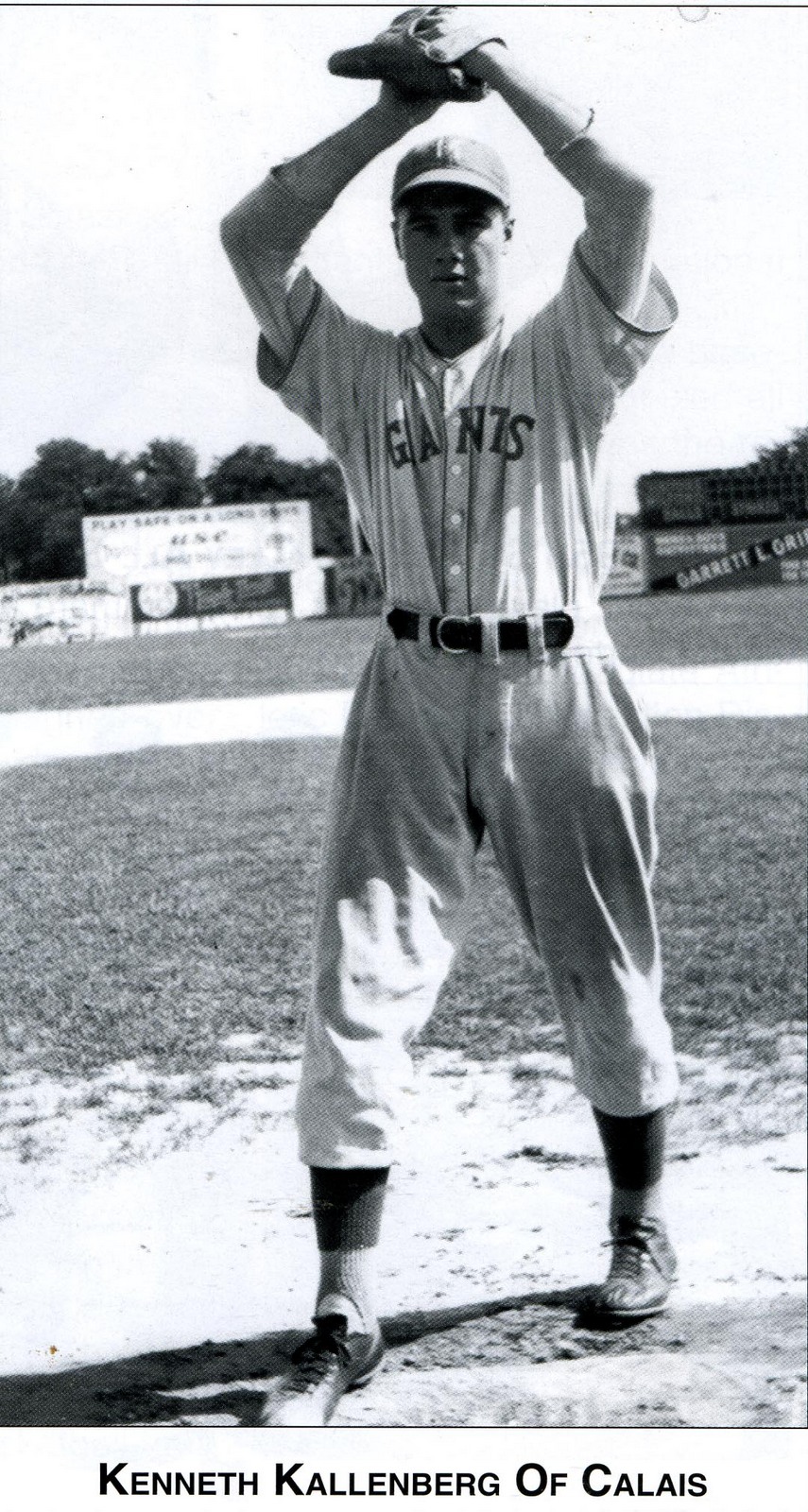

1945 saw shortages of nearly every product and commodity in the St. Croix Valley including nearly all food products, gasoline and tires. Most purchases required a ration card, and travel was strictly limited to emergency personnel such as doctors. The news was nearly all about the raging battles in Europe and the Pacific and while the war was going well in both theaters that was not necessarily the case for the families of those fighting the battles. Headlines such as “Alton Bohanon killed on the Meuse,” “Ernest Bowers of Milltown killed in Germany,” “Paul Clooney killed in Italy,” Don Mitchell Wounded,” and “Russell Kinney KIA” were common in the Advertiser. Finally in August of 1945 the war ended with the surrender of Japan, and the Class of 1945 caught a break. Had the atomic bomb not left the Japanese with no choice other than surrender, the Class of 1945 would have had to assault the beaches of Japan’s main islands. The casualties would have been horrendous on both sides. Instead servicemen and women from both sides of the border began returning home in 1945. Of the many who came home in 1945 were Ken Kallenberg, John Churchill and Bob McCarter.

Ken Kallenberg was as fine an athlete as Calais ever produced. He was a major league caliber pitcher who was playing in the Giants minor league system before going off to war. In his 1940 season he posted a 16-7 record with a 3.20 ERA in the minors and appeared destined for the big leagues. Instead he traded his Giants uniform for Army khaki and was wounded several times in the Pacific Theater. These injuries left him physically unable to resume his career upon his return. He was awarded both Bronze Stars and a Silver Star for heroism. His Silver Star citation stated:

Staff Sergeant Kenneth A. Kallenberg, (31024396), Infantry United States Army. For gallantry in action against the enemy in the vicinity of Antipolo, Luzon, Philippine Island on 14 March 1945. Sgt. Kallenberg was the guide of a Demolition Squad operating on ‘‘Hand Grenade Hill” when fierce enemy rifle fire was encountered, seriously wounding one of the squad members. The remainder of the squad was forced to seek cover, leaving the stricken man without protection and medical attention. Three unsuccessful attempts had been made by others to rescue the fallen comrade during which time four men were wounded. Sgt. Kallenberg, with utter disregard for his own safety, unhesitatingly volunteered to rescue his companion on the fourth attempt. Not knowing the exact location of the wounded man, he was forced to make several dashes in plain view of the enemy, exposing himself to the hostile rifle fire. Upon finally locating the stricken soldier, he called for two volunteer carriers, equipping each with two smoke-grenades. At his signal, the grenades were thrown and under the smoke screen the three men, led by Sgt. Kallenberg, dashed forward, reached their wounded companion and succeeded in bringing him to safety and medical attention. Home address: Mr. Arthur Kallenberg, (father) 36 Germain Street, Calais, Maine.

This very poor photo above shows John Churchill of Calais seated in front wearing goggles as his division advanced into Germany in early 1945. Churchill served with the 106th Lion Division which had the ignominious distinction of surrendering en masse to the Germans in December 1944. The 106th was a green division with little combat experience. In the late fall of 1944 it was assigned to a “quiet” sector of the front in the Ardennes Forest—a seemingly impenetrable barrier to any major German attack. In fact the Germans were then making plans for a last ditch offensive against the Allies in this very sector in the battle which became known as the Battle of the Bulge.

On December 16th, 1944 the Germans struck with every available fighting division left in the German Army on the Western Front. Within days Churchill’s 106th Division was in the rear lines but these were the rear lines of the German Army. The Germans had overrun and completely surrounded most units of the 106th in its advance to the west, cutting the division off from all supplies and communication with the main Allied armies. When the division ran out of ammunition and food the Division commander agreed to surrender his nearly 6000 men to the Germans. However he gave his troops the authority of individual initiative—they were authorized to attempt an escape to the Allied lines to the west. Scattered groups including Churchill and a half-dozen friends made the attempt and succeeded in getting back to American lines. The bulk of the division was marched off into captivity. Churchill was assigned to a reformed division which advanced into Germany in winter of 1945.

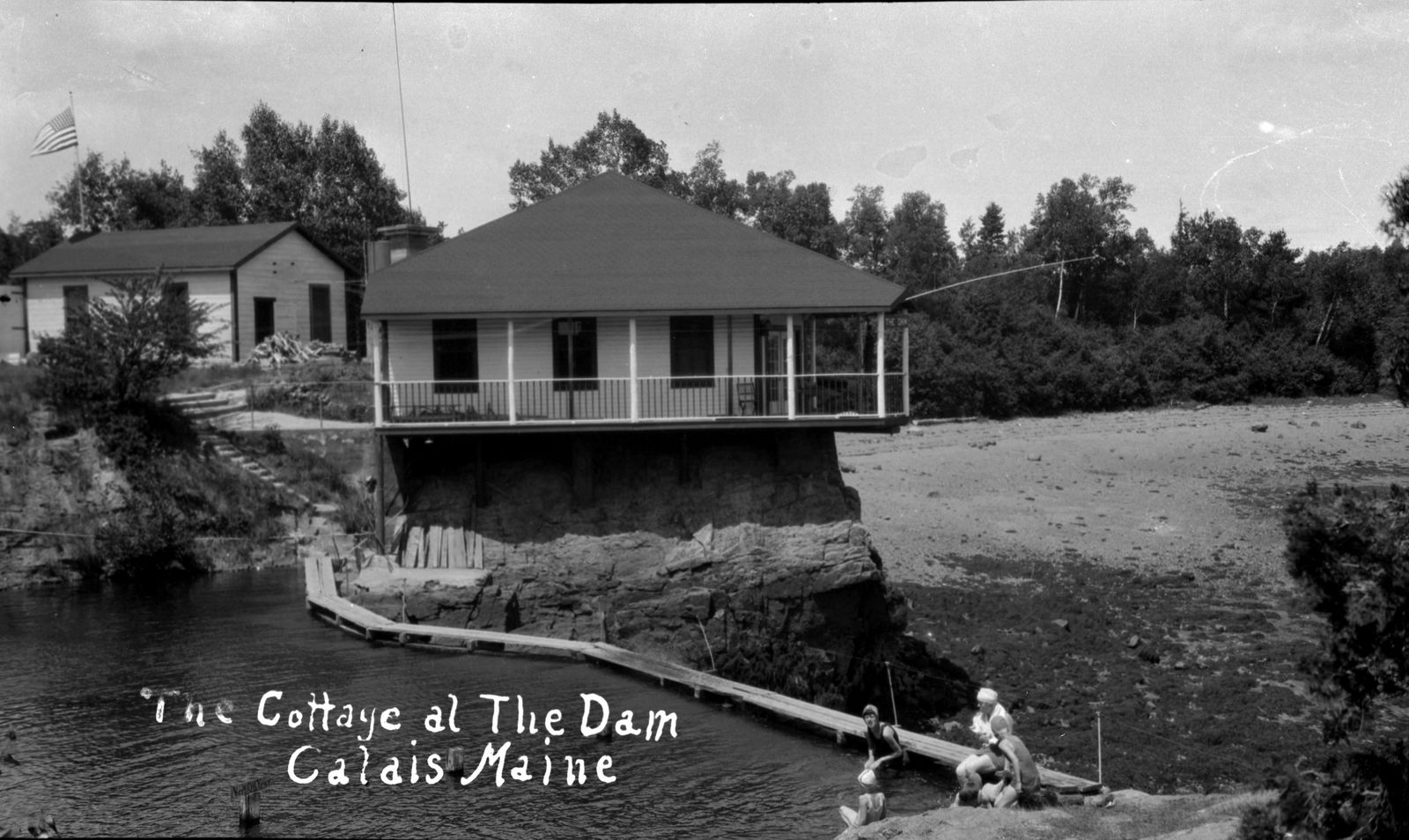

Bob McCarter was a Robbinston McCarter who had moved to California before the war. Even so, he still considered himself a local, and his family camp, known as the “Dam” still graces the St Croix just across the Robbinston/Calais line. Many are familiar with the “Dam” sign on Route One. He was a WW II fighter pilot in the Army Air Force flying P-47 Thunderbolts and later P-51 Mustangs in the Pacific with the 348th Fighter Group, 341st Fighter Squadron. McCarter was on a mission off Okinawa on August 9, 1945, when a brilliant flash of light startled him. Only after he returned to his land base did he learn that he had seen the atomic bomb explosion that devastated Nagasaki. For Bob, Ken Kallenberg, John Churchill and all the others from the St Croix Valley serving overseas this was the day they were assured of coming home alive. The resistance of the Japanese crumbled when they realized the U.S. had more of these devastating weapons than the one they had dropped on Hiroshima the day before. Troops then passing through the Panama Canal from Europe to begin the invasion of Japan were turned around and returned to the United States. 1945 graduates were able to turn their draft notices into confetti which was probably the best luck of all for the “hard luck” Class of 1945.