In 1897, a Calais schooner went missing after leaving port in Calais as it headed toward Martha’s Vineyard. Five local men were aboard. While the vessel was eventually identified when it arrived in broken pieces, the men went missing – until earlier this year, when Debra Baldwin correlated the discovery and burial of two unidentified sailors at Little River Lighthouse that same year. These are the remarks Baldwin presented that day.

Julia A. Warr Plaque Dedication Remarks

19 Sep 2017, Cutler, Maine

Debra Baldwin

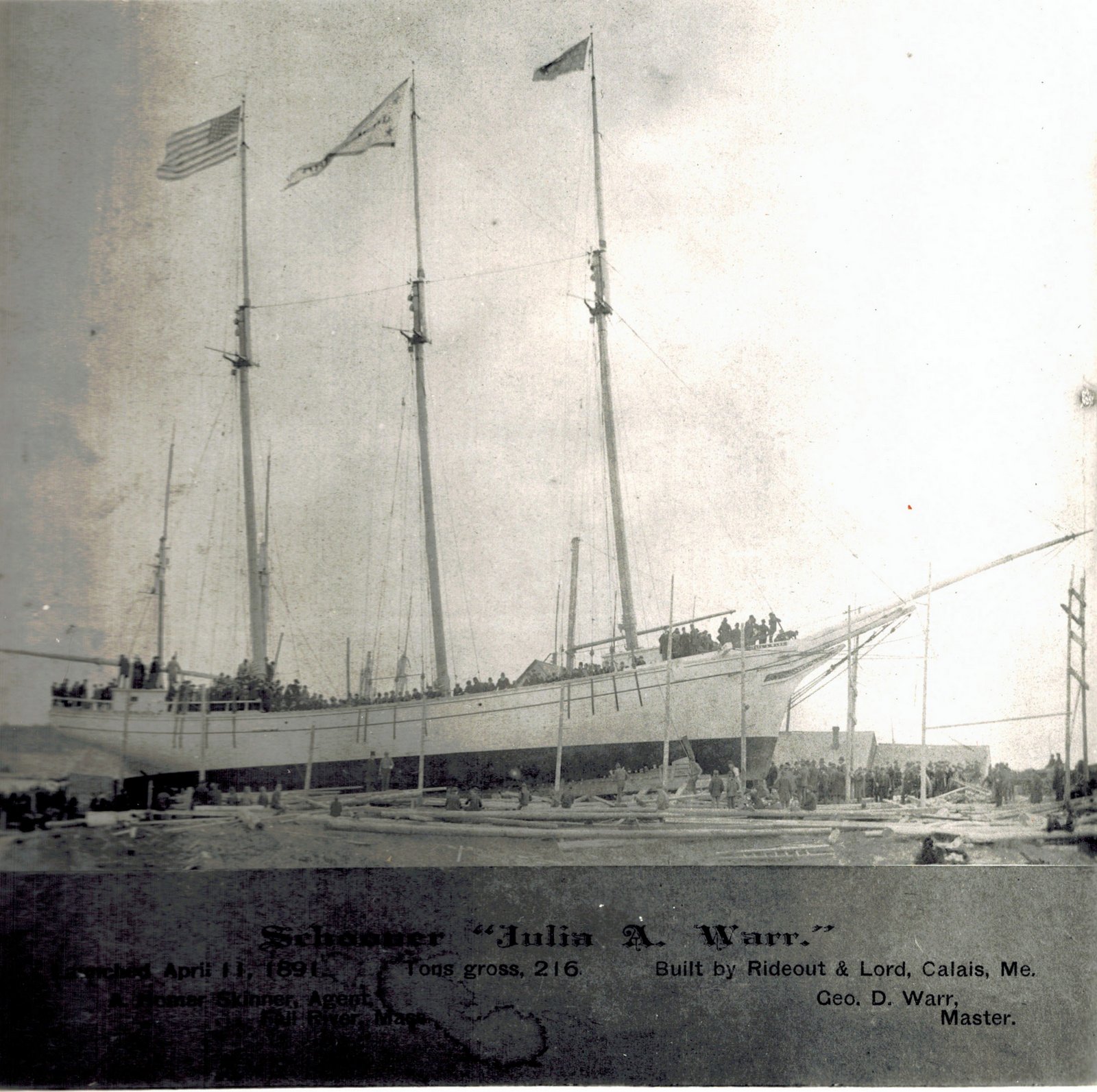

During the late 1800’s, there was a particularly large lumber industry in the Calais area with many sawmills built on both sides of the St. Croix River. Vessels were needed to transport the lumber to other locations and the Rideout and Lord Shipyard in Calais was established in 1870 in order to meet this need. 23 boats were built over the next 20 years.

One of the sawmills along the river was owned by James Murchie and Sons. They formed a partnership with Homer Skinner, a lumber merchant in Fall River, Massachusetts, and along with over 20 other investors, contracted for the Julia A. Warr to be built in 1890 so she could bring lumber from Calais to the Massachusetts area. The Julia was one of the last big ships built at the shipyard and was known for being “one of the staunchest vessels that ever sailed from that port.”

On either Thursday or Friday, Dec 16th or 17th , 1897, the Julia set sail for Vineyard Haven on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, with a full cargo of lumber, laths and shingles.

Within the next 48 hours, a huge storm struck the New England Coast that lasted at least two days moving from New York into Canada. It is somehow very fitting that we would have the same weather conditions on this very day of our ceremony. Perhaps it was a hurricane back in 1897 as well.

The Calais Times reported the known damage from the storm five days later. It read, “At Seal Cove, Grand Manan, Sunday, the schooner Sarah went ashore during the gale and became a total wreck. The crew landed at Campobello. She was laden with flour and corn, consigned to Eastport merchants. There was anxiety for the Lubec lifesavers who went to the vessel’s rescue but they returned all safe. The same day, the schooner Terrapin, bound for this port lost her sails off Long Island, but after bending new sails, proceeded in safety. The Calais schooner, Louise Boardman, which had sails blown away and boom broken Saturday in the bay was assisted and towed into port by the tug Springhill. Numerous other marine disasters in the gale are reported and in the list is included the St. John schooner L. T. Whitmore which struck and went to pieces near Fisher’s Island while bound from St. John’s to NY with a cargo of deals. The crew escaped in a boat. A dispatch from Salem, MA says the St. John’s schooner Marguerite loaded with laths was burned to the waters edge.” That makes at least 5 other schooners that were crippled or did not survive this same storm, though all of the crews were reported as being safe.

The Julia was supposed to reach Vineyard Haven by Christmas, but she never made it.

An article in The Calais Weekly newspaper shortly after the new year stated that “The anxiety for the schooner Julia A. Warr intensified Tuesday when James Murchie and Sons received a dispatch from the managing owner of the vessel, Homer Skinner, Fall River, which read as follows: ‘Fisherman reported white center-board schooner bottom up, 200 miles off Cape Cod, spruce lumber and shingles floating alongside. By photograph and description, he is almost confident that it is the Julia A. Warr, capsized and all lost. This is terrible news.’ Relatives and friends of the crew have not abandoned hope and the final report may bring better news.”

But the headline on Jan 6 was more discouraging saying, “All hope for schooner Julia Warr abandoned.” The article added, “It is thought she capsized during one of the gales three weeks ago. Relatives and friends of the schooner have given up all hope of ever seeing them again.”

On January 13, it was reported that “The Washington authorities, on information from Congressman Simpkins, Mass, ordered the revenue cutter Manning to search for the wreck which was last seen 175 miles off of Cape Cod.” But a few days later it was reported that the cutter “returned to Boston from an unsuccessful cruise in search of the derelict.”

Back in Calais, there was still brewing a glimmer of hope. “The friends of the captain and crew of the Julia A. Warr of this port still retain hopes that they were taken off and will be heard from on arrival at some foreign land.” But as the silence continued, the hope flickered out.

At the end of January, the cutter Manning was sent out one more time to look for the schooner, but again failed to sight her and returned in February with no news.

Finally, on March 29, The Boston Daily Globe reported that “The mystery surrounding the disappearance of the schooner Julia A. Warr has at last been solved, the shell of the vessel having drifted ashore near Mecox lifesaving station on Fire Island this morning. The vessel undoubtedly capsized during one of the heavy gales in December and her crew undoubtedly perished. The schooner left Calais in December for Vineyard Haven and was never afterwards heard from although a wreck passed several times in the vicinity of the South Shoal Lightship, bottom up and was supposed to have been the missing vessel.”

In April, the hull and remaining cargo of the Julia A. Warr, once valued at over $7000 were sold for $225 at the place where she grounded on Long Island.

During that last fateful trip, Captain George D. Warr of Calais was in command of the vessel. He was known as one of the most successful masters in the coasting trade. At age 44, he left behind his wife, Ida, and six children. Seaman Willis Warr, age 26, was Captain Warr’s nephew. He left behind his wife, Maude, and two very young sons.

Seaman Campbell McKay, age 44, had divorced his wife Lizzy six years earlier. It is unknown if he remarried but he left two teenage daughters behind in Calais.

The cook, Hartley Arthur Moses, also age 26, left his wife, May, and his little nine-month-old daughter, Jennie to mourn his loss.

But most tragic of all was Leon “Fred” Wilson, in his mid-20’s who had served on the Warr as mate for two years. Leon was Captain Warr’s brother-in-law having married the half-sister of the Captain’s wife. Leon and Florence had married only the week before the fateful trip. Captain Warr had sold a cottage to Leon, who was from Jonesport, to be able set up as his honeymoon home. How sad it was that he was never able to do so.

While all three of the young wives eventually remarried after their husband’s deaths, Florence did not do so until twelve years later. Surely, this must have been an extremely traumatic event for her to recover from.

While we may not know exactly which two of these five men is buried on Little River Island, we honor all of their memories today in dedicating this plaque. For 120 years, they have been referred to as the unknown sailors on Little River Island. But now we can restore their names and tell their story so that all who come here in the future may know who they are and remember the story of the Julia A. Warr.