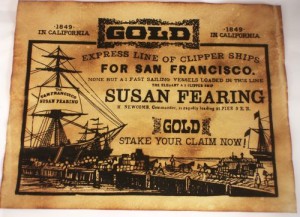

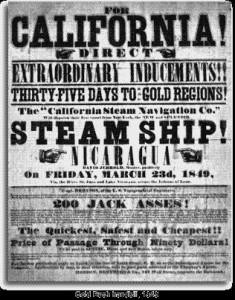

In 1849 the national insanity known as “gold rush fever” spread like wildfire throughout the United States. Even the St. Croix Valley, as distant from San Francisco as any place in the country, was in its full grip by the summer of 1849. Every week the Calais Advertiser and Frontier Journal reported on ships returning from California so loaded with gold dust they could barely stay afloat. Gold nuggets weighing several pounds were, if you believed the reports, scattered across the California landscape like rocks on a Maine beach. The locals were easily convinced and began leaving for California in droves. On June 13, 1849 S. H. Foster, Asa Rolf, Reuben and George Lowell and John Stillson left for the gold fields. The Advertiser wished them success and admonished them to return with a sack of gold nuggets.

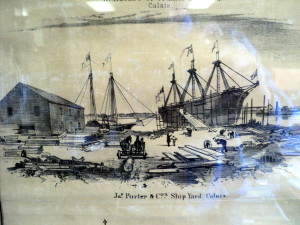

On September 10th, 1849 15 others left on the Brig Brazilia, passage arranged by Jas Porter & Co., St Stephen at $200.00 a head. So many left that by November the local papers were warning the exodus was likely to be the ruin of the City but the disease was too advanced to be checked. Even reports from California of mass murders in the gold mining towns by bands of Mexican bandits, lynching and robberies could not stem the tide. Joseph Porter had shipyards on both sides of river and arranged to send many locals to the gold fields but there others like David Eastman mentioned below who found innovative ways to make money from the gold in California.

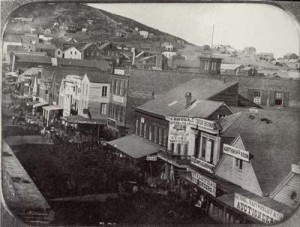

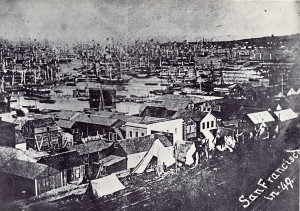

As the Brazilia left the dock in September 1849 I. S. Kelsey, Jesse Gleason, and Joseph Hay of Calais were arriving in San Francisco.Calais native Shubael Todd was on hand to greet them. His journey from Boston around Cape Horn had taken Shubael 155 days. He had sighted land only twice and one of his party, Barry Clinch, had died on the trip. Other journeys were even longer and more harrowing, especially for some who debarked at Panama and took the jungle route across the Isthmus. When they arrived in San Francisco they found a harbor packed with ships abandoned by their crews. The City was comprised largely of tents, with high wages and even higher prices and lots of misinformation about gold. San Francisco harbor in 1849 is shown above as is “downtown” , a hastily constructed conglomeration of bars and businesses selling supplies at outrageous prices.

A number of St. Croix vessels were built to carry lumber and passengers around the Horn to California. None is more interesting than the steam wheeler S.B. Wheeler built in 1849 in Eastport. In 1850 David Eastman, a St. Stephen shipbuilder, bought the 120 ton stern wheel steamer and then built the hull of the barque Fanny which was launched without decks and sunk in deep water. The empty hull of the Wheeler was floated over her and the Fanny was raised in such a manner that she caught the steamer whose engines and upper works were then stored in the hold. The Fanny was decked and rigged, and on 24 July 1850 the Calais Advertiser reported that “she is now lying in the river with the steamer in her, stowed as snug as a pea in a pod. We understand several persons have engaged a passage in her, some three or four of whom are ladies of this town.” The Fanny went around the Horn to San Francisco and from there to Bernicia where she was dismantled and sunk and the Wheeler refloated. For some years the steamer operated between San Francisco and Stockton and was then sold to Mexico. The Fanny was raised and rerigged.

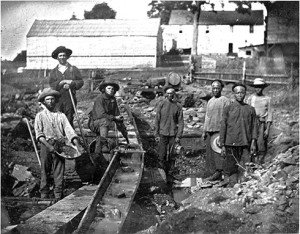

Just a year after arriving Shubael Todd had returned from the gold fields to San Francisco in time to welcome another contingent of locals, Josephus Bradford, Joseph Prescott, James Bedlow and J. Judson Ames, photo above. Ames was as interesting a Downeast character as you’d be likely to meet, even in those days of eccentric personalities populating the frontier. Ned Lamb, our most eminent historian, says this about J. Judson Ames:

“In the building in which the Calais Advertiser was so long published, J. Judson Ames, a six foot six specimen of a New England boy, kept shop and advertised that he sold “Pizen Things.” He sold pies, cakes, etc. Ames, son of Capt. J. Ames, who lived on the corner of Main and Germain Streets, was an odd genius. He made his counters to suit his tall stature and not for the accommodation of his customers. The counters had to be cut down about six inches by the next occupant of the store. Ames was among the earliest who went to California and the next heard from “Jud” Ames was that he was President of the “Handcart Society” of San Francisco. “Jud, in Calais, was noted for his patriotic airs and his elevation to the Presidency I speak of, was appreciated by the Calais community. Soon after, however, intelligence reached town that “Jud” was appointed a Judge in San Diego, when he had established a newspaper. It was on this paper that the celebrated humorist “John Phoenix” gave his humorous writings to the world. John Phoenix was a Lieutenant in the regular army and was stationed at San Diego where he and Ames became great friends.”

In fact Ames was one of the Calais natives who stayed in California and made his fortune. His contributions to California society in those early days are well documented in the historical record of San Diego where he founded one of California’s first newspapers- the San Diego Herald on May 29, 1851. The paper, a highly partisan Democratic publication, gained a good deal of notoriety and increased circulation when Judson took one of his frequent extended trips to San Francisco and asked his good friend George Derby to run the paper in his absence. Derby was as much a character as Ames and as soon as Ames was out of sight Derby converted the paper into a humorous sheet and reversed the editorial policy to favor the Whigs. Derby gained much fame as a writer and Judson forgave his friend’s disloyalty and continued to publish his articles in the Herald.

Other Calais men including Mr. Wade and George Bixby left for home after only a brief stay. Bixby too warned his friends to stay home. “ I don’t deny that there are once in a while persons who do well, but you would not wonder at it if you could see the crowds at the mines. It is hard for lumps of gold to escape being dug by someone. It is now over a year since I arrived here and I have never yet known but one man to get over $6000 in four to five months and he was lucky in finding a vein where the dust held out well.” Most of his friends and acquaintances lasted only a few weeks at the mines and returned to San Francisco, broke and dispirited. Some probably found jobs and stayed. The wages were good and work plentiful. However many returned to Calais and became prominent citizens including George Lowell who became president of the Calais Savings Bank pictured above at the corner of Main and Church Street. Lowell lived in the home on Main Street now owned by Ralph Mercier.

Of those mentioned above we know Reuben Lowell returned and married Elizabeth Emerson in 1856. Asa Rolfe of Princeton also returned and died at Princeton in 1874. It is interesting that Asa had acquired a ¼ interest in the Brig B W Roberts just before he left for California. It was probably the ship he sailed on to California. Some we know died in California or in transit. Barry Clinch died before rounding the Cape, his widow was still living on Germain Street Calais in 1887. One fellow not mentioned in the articles was Frederick Augustus Lowell, a brother of Reuben, whose name appears on the tombstone above in the Calais cemetery. He was 25 when he died in San Francisco in 1854.