Passamaquoddy History Draws International Interest

By Lura Jackson

(This article was originally published in the Calais Advertiser on May 5th, 2016. It is used here with permission from the editor.)

In its largest turnout for a presentation on record, the St. Croix Historical Society was very pleased to present speaker Donald Soctomah at its May meeting for a review of the history of the Passamaquoddy on the St. Croix River. Soctomah shared a virtual “canoe trip down the river” with a crowd that included guests from all over Eastern Washington County and parts of New Brunswick. The SCHS reported that interest in the event had been voiced by members who were located across both the US and Canada.

“The history of the St. Croix Valley is ninety-nine percent Passamaquoddy,” SCHS President Al Churchill said, expressing how little time Europeans have been in the area by comparison.

Churchill shared a story of two Passamaquoddy men who were vying for the position of representative to Augusta in 1878. Both men—John Newell and Noel Joseph—received exactly equal votes, but they themselves had not yet cast votes yet. As it turns out, the day of the voting, Newell was too sick to show up. Rather than voting for himself and winning the position, Joseph refused to cast his vote. The election was later settled when more tribe members came to vote. The scenario highlights the fair disposition that the Passamaquoddies and many other Native Americans have been known for.

“First, archeologists told us they found evidence of Passamaquoddies here going back six thousand years,” Soctomah said. “Then it was eight thousand, then ten thousand.” The most recent discovery, Soctomah explained, is one in New Brunswick dating back 13,000 years—making it one of the oldest in North America. The site included the remains of a short-nosed bear, a now-extinct omnivore the size of a grizzly. “It may have been a gathering spot for wild rice,” Soctomah said.

The Passamaquoddies are among the Native American tribes that have an extensive collection of petroglyphs, or symbols carved into rock. 700 petroglyphs have been located in Machiasport, going back 3,000 years. “The oldest ones there show religious symbols, like a powerful spirit,” Soctomah said, describing one as a stick figure with lines radiating around it. “The ones from two thousand years ago show a lot of stars and sea serpents.” The Passamaquoddies have many legends about sea serpents in the area. The last set of petroglyphs date to around 1604, when Samuel de Champlain and his group of French settlers were leaving the area. They stopped by Machiasport, and the Passamaquoddy there recorded their visit by creating a detailed image of the ship, its anchor, and its sail. Accompanying the image is a cross, signifying the arrival of Christianity in the region.

Soctomah brought three artifacts to share with the group, including an antique miniature bark canoe etched with petroglyphs matching one of the ones in Machiasport. He also shared a recording from the earliest outdoor recordings ever made. In 1890, anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes came to Calais to interview the Passamaquoddy and record their tribal songs on 28 wax cylinders. The recordings are now considered to be the second-most important in the Smithsonian collection. While grainy in their present form, Soctomah was excited to share that new technology had enabled them to be clarified, and that he would have a copy of the newly treated recordings on May 12th. “We’re going to be able to hear the old songs real clear and sing them the way the ancestors did,” Soctomah said.

Soctomah also shared that there had been a revival of interest in the Passamaquoddy language. A free online dictionary has been created at pmportal.org, and efforts to teach the youth through immersion programs are underway. Soctomah relayed that most tribes across the country have about a ten percent population that speaks their native tongue, while the Passamaquoddy now have fifteen percent. “Language is our history,” he said. “We want everyone to learn Passamaquoddy.”

Demonstrating the point, during the presentation itself the “place names” of all the locations covered were provided by an audio recording from David Francis. The names used by the Passamaquoddy are always descriptive of the land or water that is present in the area. In many cases, the Passamaquoddy names were integrated into the name most residents would commonly use.

As an example, Spednik Lake was known as Espotonek, or the “high mountain lake”. Nearby, Young’s Island would have been used a village site, or a spring site useful for cooling off during the warmer seasons. In Vanceboro, the tribe would harvest big eels, considered a delicacy. “The whole area was a network of canoe highways,” Soctomah explained, describing how if you knew the way to go you could travel to St. John or to the Penobscot area.

Soctomah was saddened to share that the building of the dam in the area had flooded a lot of the archeological sites in the region, covered 3,000 acres of land. He said that the dam had recently been relicensed for fifty years. “So we won’t have a say for another fifty years.”

He added that during Calais’ booming lumber years, the St. Croix was completely unusable by the Passamaquoddy. “One log can kill you, and there were thousands. It’s like, you’ve got your vehicle, but you can’t go anywhere.” Soctomah said that the only lumber that had been left in the region was in New Brunswick on a Passamaquoddy reservation. After being pressured by the lumber industry, the government agreed to allow it to be harvested.

Continuing on the canoe journey, Soctomah explained how the area was known as Skutik, which means “burn over place”. Spring settlements would ideally be located in low-lying areas with no trees or shrubs to limit bugs, so the Passamaquoddy would typically burn a site before placing their village.

The Moosehorn region bore the name Maguerrowock, which means “land of the caribou”. It was named as such due to the high population of caribou that would winter in the area. The last caribou in Maine was shot around the turn of the 20th century. Soctomah expressed that he was glad that the name Maguerrowock was kept intact.

The Milltown region by Salmon Falls (Siqoniw Utenehsis) was the first place in the region to thaw out, and accordingly, the Passamaquoddy would use it to bury their dead after a long winter. When Milltown was settled, 200 acres was initially allotted to the Passamaquoddy to continue the practice, however, it soon included only the rocks by the water to enable them to continue fishing there.

St. Stephen was known as Kci Uquassutile, or the “great landing”. With its many freshwater springs, the area was a favorite spot for Natives coming in from the ocean who had developed a powerful thirst from the salty air. Calais itself was called Pemskutik, again referring to how the area would be burned before the spring settlement was established.

The St. Croix Narrows was called Kpokiyok. “If you want to continue in that direction by canoe, and the tide’s coming in, just pull over and wait,” Soctomah said. “It’s really powerful in that spot.”

Soctomah also shared some legends of the Passamaquoddy as they related to local landmarks. In particular, Dunn Island (Pqapitossisk) was known as the “place of the red-toothed beaver”. Passamaquoddy hero Glooskap was said to have been chasing a great red-toothed beaver all over the waterways, trying to stop him from building dams. The beaver kept fleeing every time Glooskap caught up to him. Finally, when the beaver set up his home at Dunn Island, Glooskap decided to wait him out on a nearby mountain top. He used his tomahawk to cut off the top of the mountain and set his teepee on it directly. The mountain is now known for its distinctive flat top.

Soctomah said that Glooskap travelled around in a stone canoe, according to legend. At the Indian Township museum, there is a stone paddle that he tells visitors belonged to Glooskap (in truth, it was made by a local artist).

The great whirlpool known as Old Sow also has a legend attached to it. Glooskap was traveling around chasing giant fish that were causing trouble by making the waters all muddied. He picked up each fish and rubbed their noses, causing them to shrink to their present size. There was one fish he couldn’t catch, and when he finally did, he said, “You want to be hoggish and eat everything? Now you will swallow the whole bay twice a day,” and he locked the fish in place where the whirlpool is now. The Passamaquoddy say that looking down the whirlpool is like looking into the mouth of a giant fish.

St. Croix Island itself was known as Mehtonuwekoss, or “food storage place”. Soctomah described that in years where there was extra food, the Passamaquoddy would store it on St. Croix Island to keep it away from wolves. He also added that in recent decades, Natives had been sleeping on the island during their canoe trips. During one such trip that Soctomah was part of, his companions reported hearing someone scraping at their tents in their dreams. When it was later discovered that the French remains were still there, the Passamaquoddy stopped using it as a resting place.

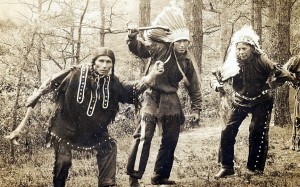

Passamaquoddy tribal historian Donald Soctomah holds up a recent donation to their archives, an antique wooden canoe etched with petroglyphs. Josephine Moore, donor of the St. Croix Historical Society Holmestead, looks on in the background. (Photo by Lura Jackson, published in the Calais Advertiser)