The summer of 2023 was certainly a great disappointment to folks Downeast. Nine of thirteen Fridays were rainy and the weekends following were equally dismal. Party boats seldom left shore, hikers and canoers found raingear essential while sales of sunscreen must have reached an all-time low. The National Weather Service reports in its 2023 summer weather review for Maine:

Precipitation was above to well above average and ranged from 125 to 200 percent of normal. The greatest departures from average were in parts of coastal Washington County as well as portions of the Central Highlands and in Southwest Penobscot County.

Many claim the summer of 2023 was the worst in living memory and others go so far as to assert it was the “worst ever”. The former may be correct depending of course on their age but the latter are far off the mark. The “worst summer ever” Downeast was the summer of 1816, better known as “eighteen hundred and starved to death.” Historians have felt comfortable claiming the summer of 1816 caused “The last great subsistence crisis in the Western World.”

Jane Sax wrote a piece in the Advertiser some years ago summarizing the brutal summer of 1816:

The year was 1816, or old “eighteen hundred and starved to death” as it was named by some surviving the experience. Residents of Washington County eagerly awaited spring that year especially May. After the ravages of winter had receded, the balmy breezes returned, the grass greened, the budding of the flowers and trees was imminent and the planting of gardens made the promise of May very sweet.

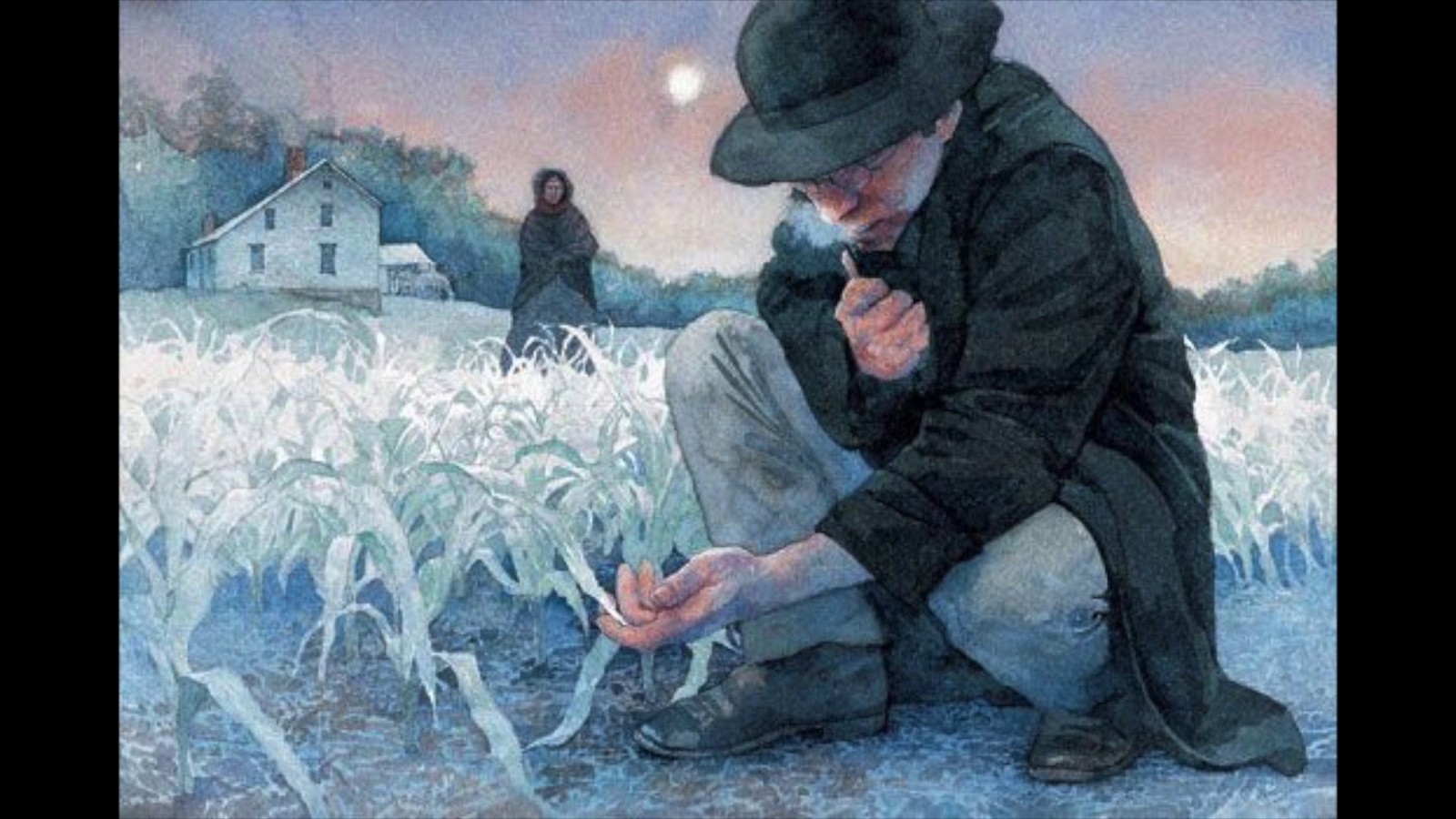

In 1816 the buds did sprout but the frost came. Within one night most vegetation was blackened and useless. Fields had to be replowed and replanted, ice formed in the pools. June was eagerly awaited.

The “Month of Roses” came but it was wrought with more surprises. More ice and crop loss brought desolation to Washington County, indeed all of the northern hemisphere. The temperature sunk so low in the tube it shocked the old timers. Frost, ice and snow were common. Almost every green thing responded to the few days of warm weather but, with more frost and snow, dies. One snow storm deposited 7 inches.

July, beautiful wonderful July! It was accompanied by more frost and ice. It was one of the coldest Independence Days Celebrations in history.

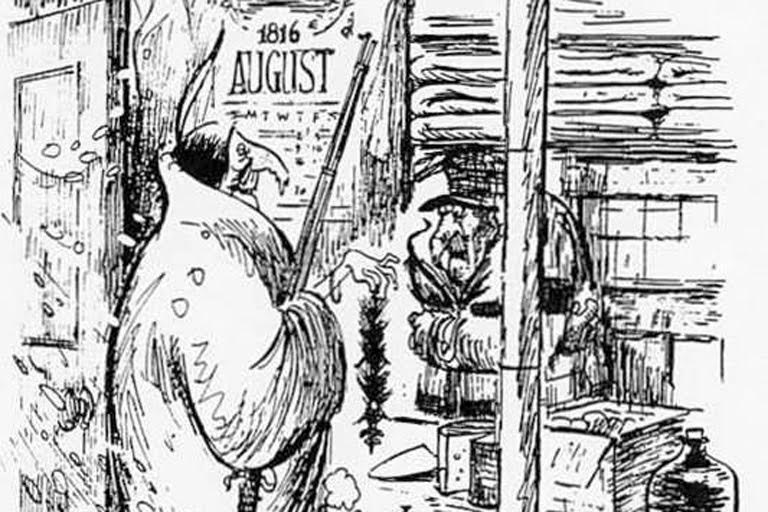

August brought some relief but of short duration. One newspaper said “the people of Washington County are downcast, their spirits as low as the thermometer.”

The last month of summer proved to be the mildest month of the year but by the third week a black frost came. Residents began to prepare for a very hard winter. The hardships of 1816 were experienced all over the world, and the ramifications lasted several years, some did not survive.”

Locals had little to offer in trade in 1816 and traders had almost no food to sell

If anything, Jane Sax greatly understated the distress of the summer of 1816. Parts of Europe, the Northeastern United States and eastern Canada were some of the geographical areas most affected by the sudden change in climate. The climate worldwide was described by those living through that remarkable summer in apocalyptic terms. Many worldwide believe the gods were wreaking a terrible vengeance on man. The “Wrath of God” was a common explanation for the misfortunes occasioned by the bitter cold or, as put by the London Times, “a visitation from heaven causing great apprehension and alarm.” Churches, temples, and synagogues filled with the faithful and not so faithful asking mercy and forgiveness for their sins. Churches worldwide offered prayers for sufficient warmth to save the crops. Famine threatened some parts of the world and in Europe rioters carrying flags reading “Bread or Blood” paraded through the streets of the capital cities.

Corn was an especially important crop in 1816. Although replanted after each freeze little survived

Local histories are replete with references to that brutal summer.

John Dudley, Alexander historian:

“Eighteen hundred and froze to death” was 1816. It was also called the year without summer. Some weather observations from around the state: May 24, freezing rain; June 5 & 10, snow; July 5, ice; July 9, corn all dead; August ½ inch ice on pond; Prices of food rose to unheard of figures – three dollars a bushel for wheat…. Afflicted families turned to milk and raspberries, which thrived. When there was nothing else, they ate clover and stewed roots.

From a Machias Union article in the 1880s:

“A well-known farmer informs us that 65 years ago on the 6th day of June 1816, the snow was 6 inches deep in almost all sections of the state. It was so cold that birds froze in June, sheep and cattle died of cold and hunger. No crops were raised. The old people all over eastern Maine remember it as the ‘year of distress.’ The late Owen McKenzie froze his ears that fateful year in June.”

From a history of Baileyville:

1816, was the coldest year of the century in the Schoodic region. There was snow on the ground in June and there was a freeze every month of the year. In 1817 the whole area was shaken by an earthquake. Those calamities, including a severe epidemic of diphtheria back in 1804-1805, left the original settlers’ families still intact and even larger by the time more prosperous times came around in 1820.

The Farmer’s Almanac reported:

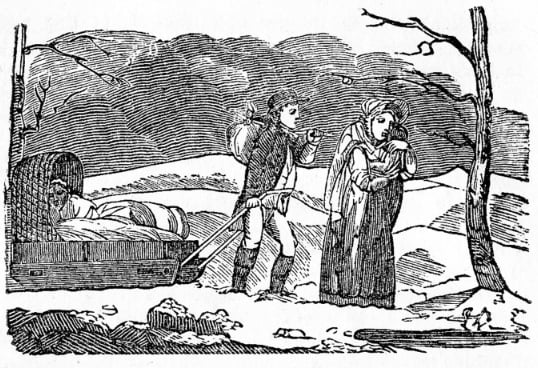

Many residents of New England and the Canadian Maritimes froze to death, starved, or suffered from severe malnutrition as storms bringing a foot or more of snow hit hard during May and June. Many others from the region pulled up their stakes and moved to Western New York and the Midwest, where the cold was less severe. In fact, the year without a summer is now believed to have been one of the major catalysts in the westward expansion of the United States.

The weather in 1816 probably stimulated western migration from this area. A history of Calais business published in the 1880s stated:

During the year 1816 the farmers were robbed of much of the rightful reward of their toil by unprecedentedly cold weather extending over nearly all New England, there being a snowstorm in June, and sharp frosts every month in the year. There came dangerously near being a famine, and there was considerable suffering, even among the hardy settlers who could eat anything and everything. To vary the monotony of this chain of misfortunes there happened in 1817 a severe earthquake which shook things up in a rigorous and impartial fashion, but did no great damage, and this was the parting kick of the demon of bad luck, for the people gathered a goodly harvest in the fall of 1817, and in 1818 business began to pick up and money became more plentiful. This gratifying condition of affairs continued and in 1820 Calais had attained a population of 418.

Tambora erupted in 1815, tens of thousands died on the island

There was a scientific explanation for the calamitous weather during the summer of 1816-climate change. Not the gradual but ultimately more destructive change in the climate we are experiencing today but a sudden event which altered the earth’s climate for nearly three years. In April of 1815 the volcano on Mt. Tambora in Indonesia erupted in the world’s largest volcanic eruption in historic times. Four times the power of Krakatoa, many thousand times greater than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945, the eruptions spewed a plume of dirt and volcanic ash into the stratosphere which gradually circled the globe and resulted in “eighteen hundred and starved to death.”

While the explosion itself was heard for a thousand miles it was many months before the news of the eruption reached the United States and no one at the time connected it with the freakish weather.

Newspaper reports in 1816 were alarming to say the least especially as regards the crop failures. In 1816 nearly everything a family ate was produced within a ten-mile radius of the dinner table and the bitter cold weather had killed off nearly all the crops.

Boston Globe- “Frost, ice and snow were common in June. Almost every green thing was killed, and fruit was nearly destroyed. Snow fell to a depth of three inches in New York and Massachusetts and ten inches in Maine.

Small lakes near Quebec City were covered with ice in the middle of July “parts of which were strong enough to bear the Indians” reported the Greenfield Massachusetts Recorder.

The Buffalo Gazette reported freezing temperatures in Quebec City on June 7, 1816, , a foot of snow and “birds which are never found but in the distant forests resorted to the city and were met with on every street and even among the shipping. Many of them dropped dead in the streets.” The reports of birds falling from the sky were common.

Those who lived near the coast were somewhat luckier than those inland. 1816 was also called the “Mackerel Year” because people on the Maine coast resorted to eating mackerel as a substitute for ham and bacon which were scarce as so much livestock had died. Those living in the interior had little access to mackerel or any other alternate supply of protein. A Massachusetts newspaper warned that the wheat and rye crops had completely failed and even “farmers of 3 or 400 acres of land will hardly be able to raise their own bread.”

Migration from the Northeast to the Ohio region set back development in the Northeast for several years

Many New Englanders not knowing the reason for the sudden change in the climate foresaw more such weather in the future and packed up and went west after the summer of 1816. The Portland Gazette in July 1819 called the migration “Ohio Fever” and complained that “many a fine farm was sold off for a wagon and a span of horses, and farmers that today were comfortable seated in the midst of large possessions, by tomorrow had melted them into just cash enough to convey them to Ohio. It was really a raging epidemic. “

There is no doubt that 1816’s cold summer was the most significant meteorological event of the century and may perhaps be unequalled in recorded history. 1816 is the only instance of zero recorded tree growth in the United States. Local history confirms the devastating effect it had on the local economy which required several years to return to growth. Consider the population figures for Calais. Between 1800 and 1810 the population of Calais quadrupled. Between 1811 and 1820 Calais did not grow but between 1821-1830 it resumed its earlier growth. “Ohio Fever” may well have been a significant factor in the economic malaise of Calais between 1811-1820.

On a positive note, we owe the eruption of Tambora for some famous literary works. Writers Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and William Polidori were vacationing at Lake Geneva during the summer of 1816 and found themselves confined to their lodgings by the cold, wet weather. Lord Byron challenged the writers to produce a truly scary story. Such was the inspiration for Shelley’s Frankenstein, Byron to write “The Fragment” which inspired the book Dracula and Byron to pen the poem Darkness:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream

The bright sun was extinquish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the external space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went-and came, and brought no day.