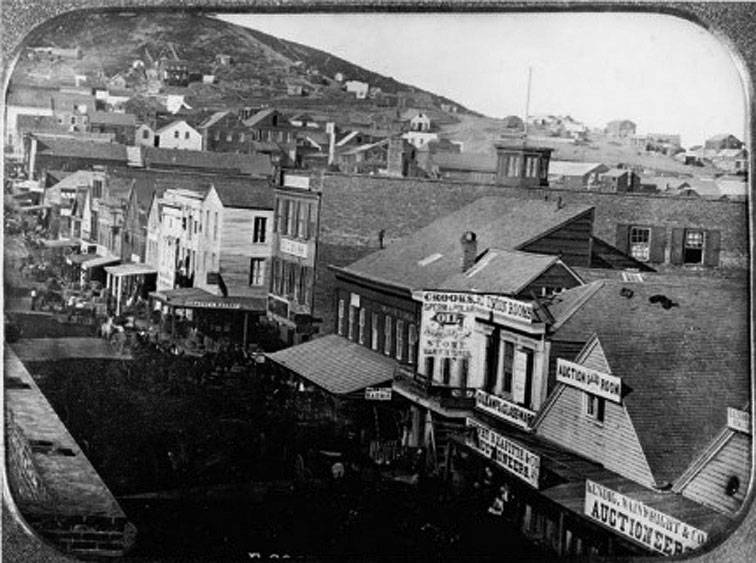

Ada passengers would have walked this Main Street in San Francisco in 1850

In part 1, we left the barque Ada and our local gold rushers in San Francisco Harbor in the spring of 1850 following a 7-month journey around Cape Horn. They would have disembarked to a city unlike any in the world-lawless, expensive, crowded with thousands of people in search of gold which, if one believed the papers back east, was simply a matter of filling a sack with the nuggets lying about. Turns out luck and a lot of backbreaking work was required and even then, most got only the broken back.

When the passengers from the Ada disembarked what awaited them was probably not at all what they expected.

Contrary to sensational newspaper reports back East gold nuggets were rare and gold dust hard to extract even from a rich lode.

The letters from California to the folks back home on the conditions in San Francisco were in general agreement with the assessment of early Calais 49er I.S. Kelsey:

I think it would take a salary of $5000 per year to induce me to become a resident of this city- The wind has the air continually full of dust. It is the driest dustiest City I ever saw- Calais dust is nothing to it. Unfortunately, the gold dust in the hills was not as plentiful as the dust in the air of San Francisco.

In letters to the Frontier Journal of Calais in March of 1850, Kelsey describes the life of a miner. About the quantity of gold, he says:

You may enquire, is there no gold in this country? I answer that it is sown and broadcast over a large extent of the country, but the trouble is, the quantity in many places on a given space, will not pay the expense of removal.

The process of extracting the gold from the earth was back breaking work which required shoveling the ore into a device similar to a baby’s cradle.

You cannot obtain so much as a tablespoon full of dirt without using the pickaxe and it must be swung vigorously to penetrate the soil, it is so cemented together. Having dug up the dirt and emptied it into the square box at the head of the cradle, we seize the staff and proceed rocking back and forth to the tune of Long Lucy, continually pouring water in with a long handled dipper, which we hold in the right hand. The water and the motion dissolve the cemented earth, and it passes through the box, drops into the apron, and descends to the bottom of the cradle. Having passed through 20 or 30 pails full we remove the box and apron, turn on water and wash off a portion of the dirt and gravel, then draw off our plugs and suffer the balance to run into a tin pan. We then, after a peculiar manner, wash off everything until we come to the glittering metal, sometimes obtaining from the above quantity one dollar, sometimes eight. Two hundred and fifty buckets is a good day’s work for two men.

Not surprisingly Kelsey advised his friends in Calais not to be in a hurry to follow him to California.

I advise all who are unfitted for, or unacquainted with hard labor and exposure, to remain where they are- to the strong and energetic I give no advice. Gold cannot be shaken from the trees.

Shubael Todd of Calais returned to San Francisco after a year in the gold fields a few months after the Ada had arrived and found that Thomas Wade and George Bixby who had been on the Ada were already on their way back home. He too warned his friends to stay home.

From letter to the Calais Advertiser:

I don’t deny that there are once in a while persons who do well, but you would not wonder at it if you could see the crowds at the mines. It is hard for lumps of gold to escape being dug by someone. It is now over a year since I arrived here, and I have never yet known but one man to get over $6000 in four to five months and he was lucky in finding a vein where the dust held out well.

1850: Diary of W.D. Lawrence of Calais

“The mud is knee deep here in the streets. Gambling (is) the principal business. The Sabbath is almost wholly disregarded (there being) dancing, gambling and all kinds of amusements as well as business of other description. Attended a Baptist meeting the next Sabbath after my arrival, and it seemed somewhat odd to pass and repass such scenes of revelry while making my way to the house of worship.”

For about two weeks, apparently, Mr. Lawrence and several others, identified only as Rolfe, Todd, Smith, Porter and McAllister from Calais (Maine), made plans and secured sufficient provisions for staying and working in the gold fields.

“About April first our company started for the mines and after various hardships and privations arrived there near the Stanislaus River southeast of San Francisco. Two days after our arrival I commenced digging for gold, my first attempt. What was made in the afternoon amounted to about $5. Next day it was about the same. We continued digging for about ten days, the proceeds being about $60. A California paper containing my own and six other deaths was placed in my hands.”

Most of Shubael Todd’s friends and acquaintances lasted only a few weeks at the mines and returned to San Francisco, broke and dispirited. And what of the passengers on the Ada? With the help of Sharon Howland, Calais historian and genealogist, we have managed to trace some of Ada’s passengers although not a few disappeared into the mists of time without a trace.

Freeman Alwood (Alward) the author of the diary in which the story of the Ada is recounted was one of the few 49ers who managed to “get some gold” but little good it did him. He started for home with his cache but was waylaid by bandits who robbed him and left him for dead on a rock, badly wounded. Friends found him, patched him up and got him a vessel home. He arrived home a broken man and soon died of his injuries.

As noted above Thomas Wade and George Bixby lasted only a few months in California and were on their way home by early August 1850. Bixby died in St. Stephen in the spring of 1881 at age 62. James Graham likewise returned home in time to be included in the 1850 census.

Author and playwright Thornton Wilder had Downeast roots.

Amos Wilder returned from the Gold Rush perhaps somewhat richer. His father was Theophilus Wilder, an early settler and mill worker in Milltown and after Amos returned, he married Charlotte Porter of St. Stephen. Having at least modest means on his return Amos went to dental school in Baltimore and practiced dentistry in Calais. The couple had a son who they named Amos Parker Wilder who spent his younger years in Calais before the family moved to Augusta when he was six. Amos Parker Wilder had a distinguished career in government, academics and as U.S. Consul to Hong Kong and Shanghai. He is most famous however for being the father of Thornton Wilder (1897-1975), a pivotal figure in the literary history of the country in the 20th century. Thornton Wilder was both a playwright and a novelist, winning three Pulitzer Prizes for The Bridge of San Luis Rey and for plays Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth. Several members of the Wilder family are buried in the Calais cemetery.

Aaron Peabody returned to Calais quickly enough to be listed on the 1850 Calais census. His occupation was blacksmith which one would have thought was a skill much in demand in California in 1850 but he must have decided soon after stepping off the Ada that home looked much sweeter than when he left. This is not surprising as the shock at the conditions in gold country was often swift and not a few took the first opportunity to return home. By 1856 Aaron Peabody was living in Iowa with his wife Mary Tyler Whitney of St. Stephen. During the Civil War he served in the Iowa Cavalry from 1863 to the end of hostilities and eventually moved with his family to Missouri where he died in February of 1884. Three of Aaron and Charlotte’s four children were born in Calais, one Aaron Filmore, was just a year old when Aaron, Sr. boarded the Ada for the trip around the Horn. It must have been a difficult time for Charlotte, left with three children, the oldest 5, while her husband sought his fortune in California.

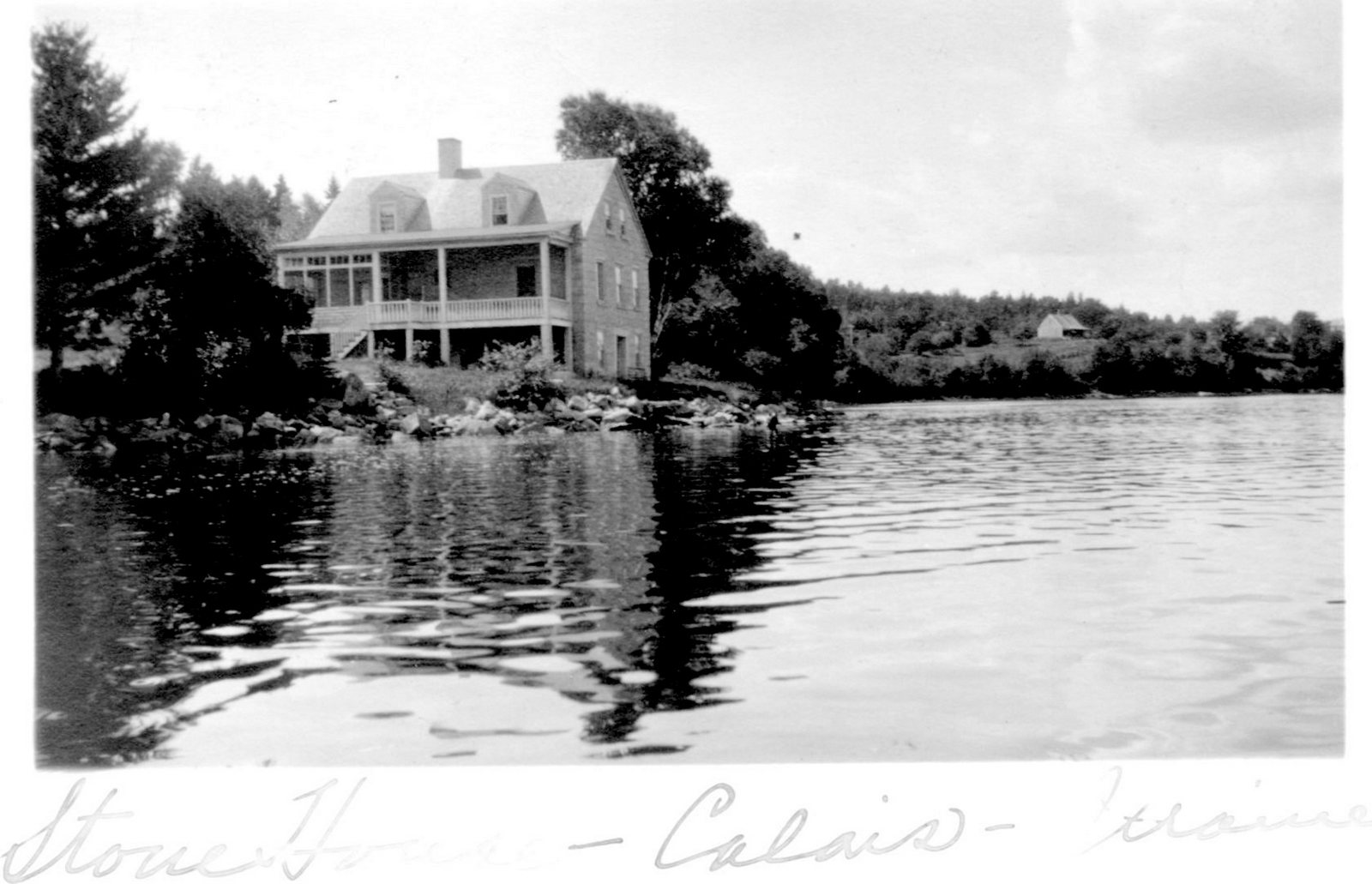

The Stone House just across the river from the Ledge In St. Stephen was a ship’s chandlery in 1849

Andrew Todd returned to Calais and related some facts about his journey to California in a conversation with Frank Livingstone, a member of the Calais Livingstones who owned the Stone House on the River Road. Frank subsequently related the conversation to Brand Livingstone who transcribed it. The conversation at the Parker House in Boston probably took place in the late 1800’s.

When Andrew Todd made his trip to California in 1850, his crowd had bought a vessel in Nova Scotia, but according to the law as they were sailing for another United States port it was necessary to hail from one to keep within coasting regulations, so they tied up at the Stone House wharf, loaded some provisions from the ship’s store in the basement, and then set forth for the gold country.

This story was repeated to my Uncle Frank Livingstone many years ago when he was lunching with Andrew Todd one day at the old Parker House in Boston. Mr. Todd stated that the only stop they made was at an island on the West coast of South America and there on that island they found but one white man among the natives. Andrew Todd was asked for his story and why he stayed there. His answer was as follows: Well, he said, I have married a native wife and am happy. When I was in the United States, the last job I had was driving a stage way down in Maine, between Eastport and Lubec, and Calais and Eastport.

The account does raise some questions. While there is no doubt the Andrew Todd who lunched at the Parker House with Frank Livingstone was the Andrew Todd who sailed on the Ada, the claim of a “native wife” and driving a stage does not fit Andrew Todd’s history. The Todds were one the richest families in the St. Croix Valley and it seems unlikely any Todd ever drove a stage Downeast.

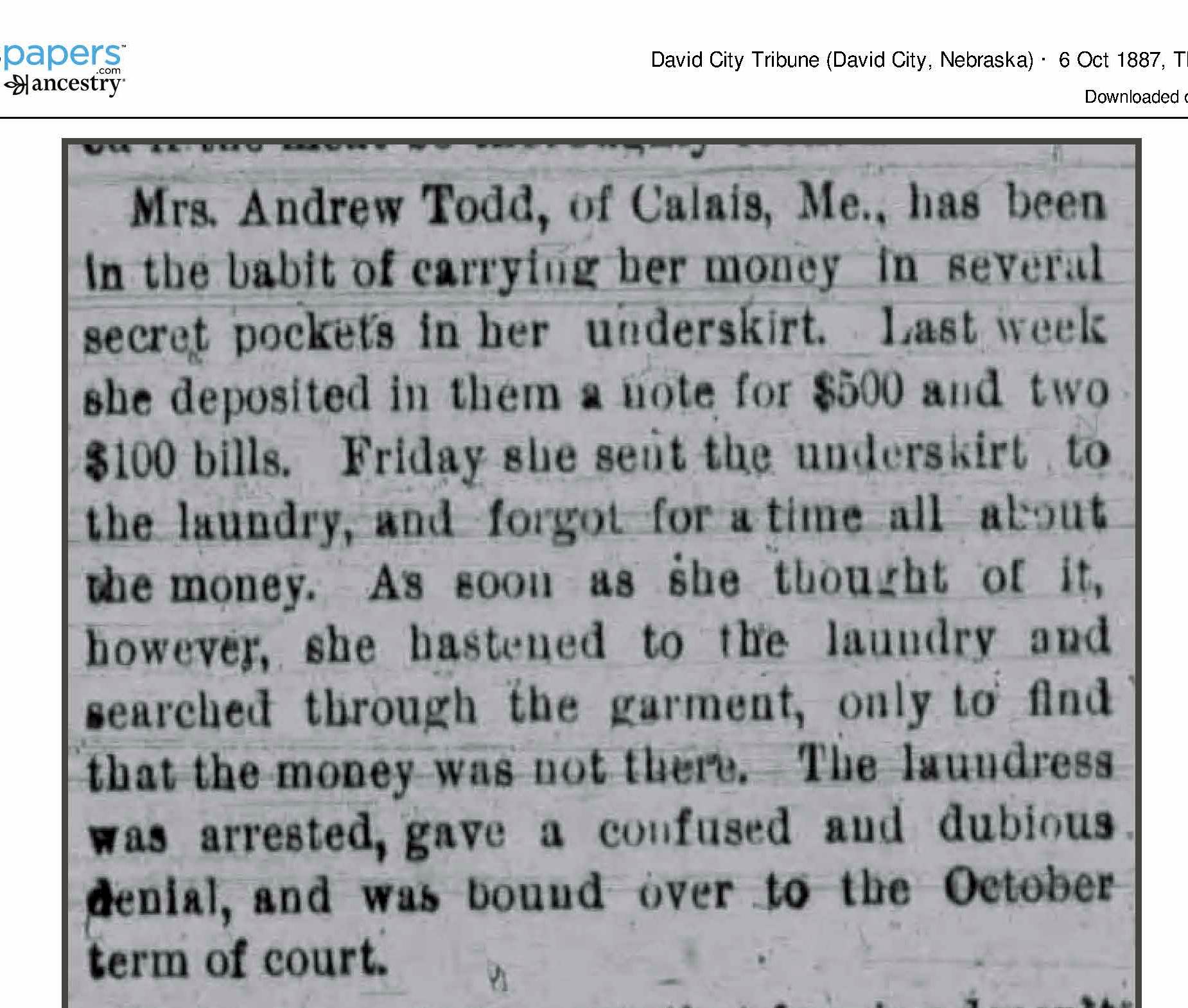

The national papers carried this interesting article about Mrs Andrew Todd in 1887

Further the wives of stagecoach drivers seldom carry large bills in their underwear and former stagecoach drivers are not usually found lunching at the classy Parker House in Boston. Perhaps Andrew did strike it rich in California but if so, he was a rare bird. More likely the money grew on trees, the thousands of acres of trees owned by the Todd family.

Dr. Francis Burke, the composer of poems, songs and even the obituary of the unfortunate Mr. Brockway who was buried in the Falklands, died of cholera in Sacramento California about a year after disembarking from the Ada. Given the living conditions in California at the time, disease was rampant and more of a threat to residents than brigands and accidents in the gold fields although both took a heavy toll on the 49ers.

Ira Brown made it home and settled on the Ledge below St. Stephen where he had boarded the Ada. He lived until 1896 when he died from the “effects of la grippe”.

Most of the sailors who manned the Ada likely abandoned her after the barque dropped anchor. Certainly, sailor Andrew Hutchinson appears to have caught the gold fever and stayed out west as he is reported in the St. Croix Courier to be in White Pine California in 1870.

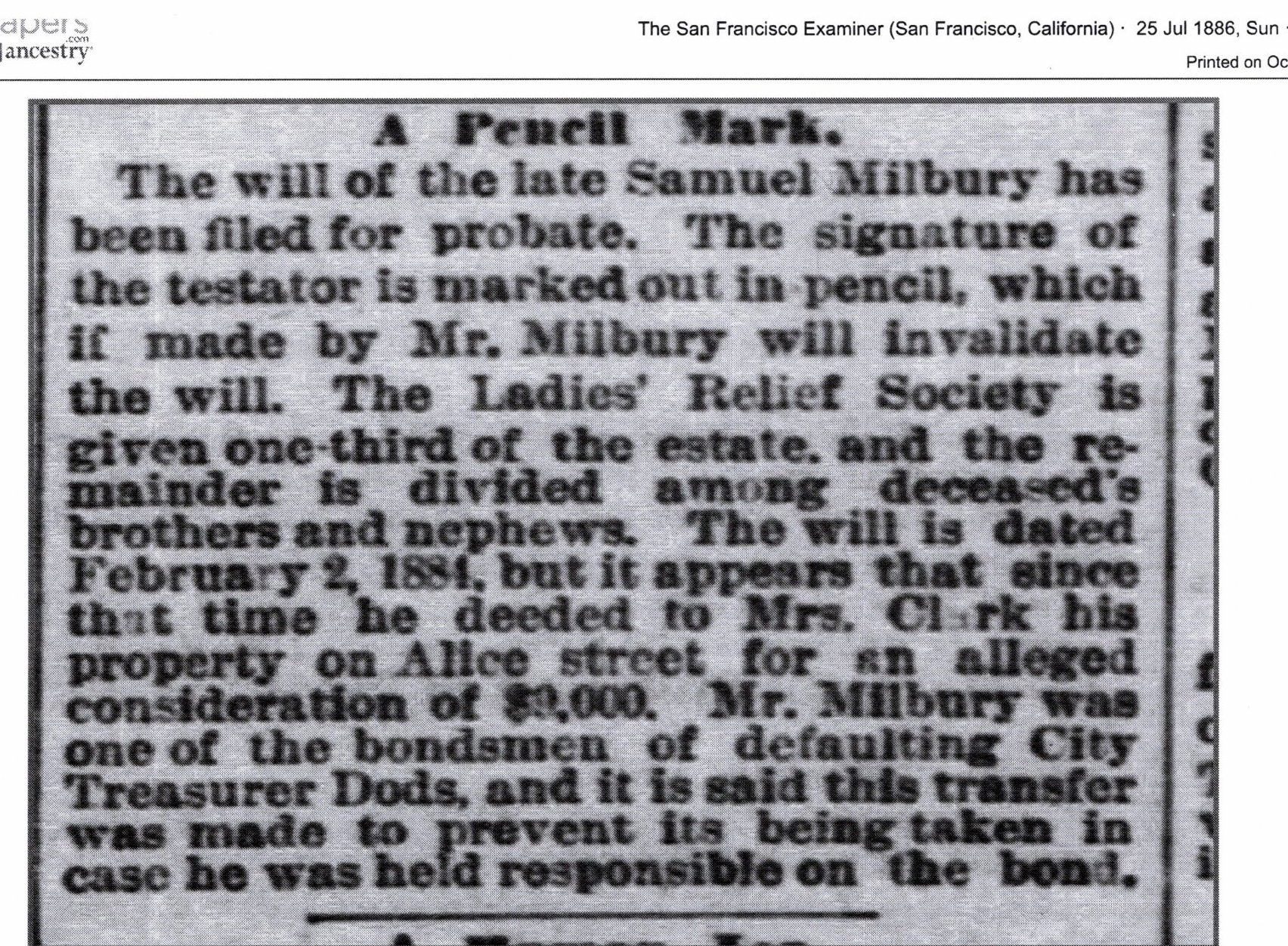

The only woman on the Braque Ada was Ann Milbury, wife of fellow passenger Samuel Milbury. It took a good deal of research by Sharon Howland to uncover their post-49er history. They never returned to the east coast but made lives for themselves in California, finally settling in the Oakland area. They were childless but deeply involved in the politics and business community of the early Oakland area. Initially listed as “farmer” on the census, by 1870 Sam was described as “retired farmer” and by 1880 had apparently moved into the city proper. He owned at least two valuable properties and was on the local governing board. He became involved in a bitter dispute over the charters of competing railroads and was arrested in the “Franchise Scandal” of 1879 and became an object of derision by a section of Oakland society. Ultimately no charges were brought.

Ann Milbury died in November of 1881 and Samuel in 1886 when a legal battle began over his estate which consisted of the two Oakland properties.

The lady in the photo above is probably Sarah Prescott, heir of Sam Milbury. At the corner of Main and Lafayette it was more recently the Jane Todd house.

His will was not allowed because someone, Sam himself perhaps, defaced the signature and Sam Milbury was declared to have died Intestate with his heirs being his nieces and nephews including many from Calais including Mrs. John Prescott, Mrs. J.H. Todd, Mrs. John S Stout, and Mrs. Henry Balcone. All would have benefited had Sam not deeded the property before his death to a Harriett Clark, described by the Oakland papers “as a vigorous, shrewd, cunning designing, captivating woman”. The estate administrator moved to set aside the deeds but eventually gave up and settled with Mrs. Clark for $600. It is doubtful any of the Calais heirs received anything from the estate.

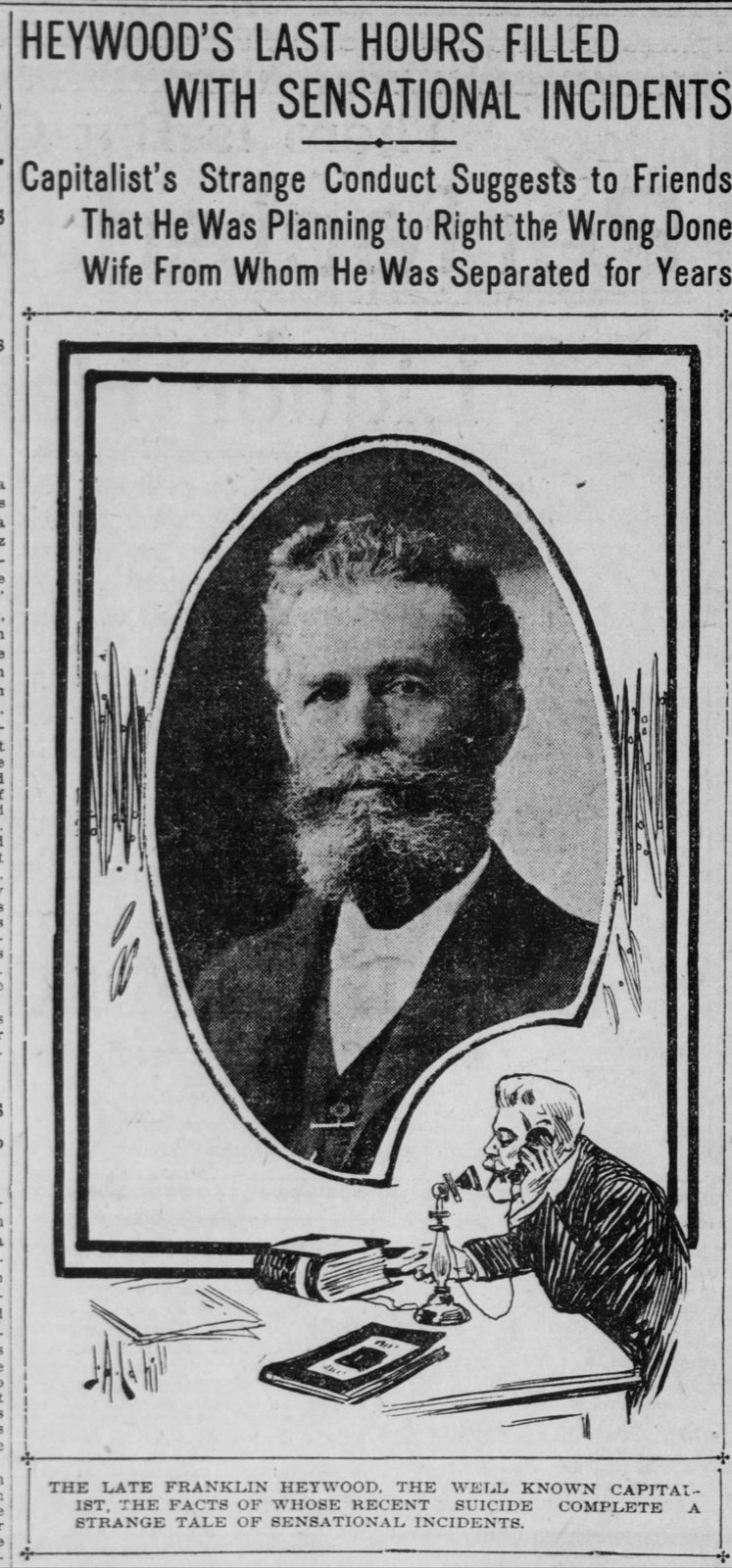

Franklin Heywood’s suicide in 1903 was a media sensation

The three Heywood brothers, Charles, Samuel, and Franklin were the most successful of the passengers on the Ada although they never found even a speck of gold. Oddly their father Zimri Heywood is said to have arrived in San Francisco at the same time his three sons arrived although he is not mentioned in account of the voyage of the Ada around the Cape. Regardless, the three boys and Zimri seem to have tried their hands at prospecting for about a month before returning to the coast to engage in more lucrative endeavors. According to Zimri’s 1879 obituary:

Zimri B Haywood was born May 24, 1803, at Waterville on the Kennebec River State of Maine. His early life was that of a hard-working boy, working on the farm and in the woods. In 1833 he went to Calais Maine and engaged in the sawmill business and afterwards as a merchant. With his three boys Samuel, Charles and Franklin, he came to California by way of Cape Horn in September 49 and arrived in San Francisco April 8th, 1850, on the landing with only an English sovereign has his whole wealth. He worked in the mines above Marysville for a month and returned to San Francisco to live, as most settlers did, in a tent. By steady industry and frugality, he saved, with the assistance of his sons, enough money to buy his first piece of property on Pacific and Kearney Streets, and he then commenced the lumber trade in which he remained until 1877.

In fact, Zimri and his sons were involved in several businesses on the coast, and they became wealthy. After his death the boys continued to operate the family businesses and the Heywoods are generally considered one the important pioneering families of San Francisco.

Franklin Heywood’s home in San Francisco

Franklin in particular was successful in business. In 1888 he had Charles Havens, a prominent architect, build an elegant home on Baker Street in San Francisco. His wife Agnes B. Heywood and an adopted daughter Agnes Maud Heywood lived in the home with Franklin until a conflict arose between his wife and the adopted daughter. His wife left the home and under a separation agreement she was paid a monthly allowance.

The battle over Franklin Heywood’s estate went on for years

This arrangement continued until a night in 1903 when Franklin, distraught at the conflict between his wife and daughter for which he blamed himself, put a gas hose in his mouth and committed suicide. Thereafter a long and bitter legal battle raged over the estate valued at $250000, a fortune at the time, involving his wife, the adopted daughter and his sons who were named trustees of the estate assets. Both wife and daughter were to receive a monthly stipend until the death of his wife when the estate was to be divided equally between his adopted daughter and other relatives. There was, however, evidence that Franklin had changed his will just before his suicide in a way more favorable to his wife but the court found otherwise. His wife unsuccessfully appealed the decision for many years.

So ends “The Rest of the Story” for some of the 49’ers who sailed on the Barque Ada. The rest probably have interesting stories to tell also and we challenge those of you with the inclination to do some “digging.”