Boys lounge on Campobello’s rocky shore early 1900s

This Passamaquoddy Bay is a vast and splendid archipelago, bigger and finer than the archipelago of Greece, among whose tempting islands Ulysses got lost. If one had a steamboat at his call he could, I suppose, travel a month here without going the same trip twice. W.A. Croffut, Journalist and World Traveler. 1890

The most beautiful island within the bay is generally conceded to be Campobello which though in British Territory was nearly within a stone’s throw of its American neighbor. The Island was granted by the Crown to William Owen, a British naval officer, in the 1770s and remained in the Owen family for a century. Its beauty, climate and other attractions had not gone unnoticed in the American press. Campobello and Quoddy generally were lauded for the coolness of the summers and said to be “the second healthiest locality in the United States, San Diego standing the very first.” Further Croffut, quoted above, wrote in the New Era of Humaston Iowa in September 1890 “No where on this continent, except perhaps in the Thousand Lakes in the St. Lawrence, are there such varied and charming vistas of interlaced land and water and even that lovely interior archipelago lacks the grandeur of precipitous coasts and tumultuous seas that are present here.”

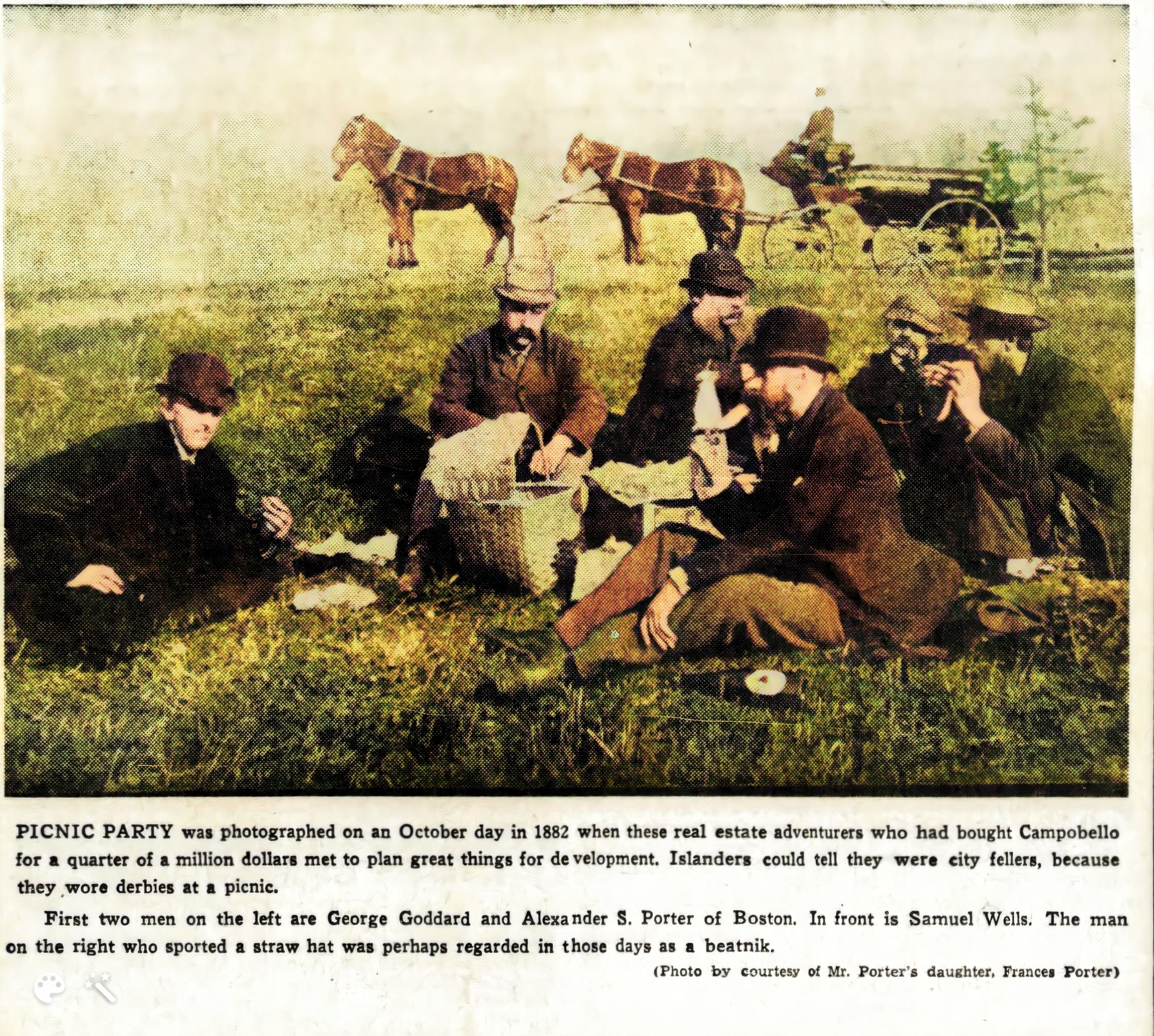

In 1881 this group of Bostonians bought much of Campobello

Given these accolades it is not at all surprising that in 1881 a group of wealthy Bostonians formed the Campobello Land Company and purchased much of Campobello including the lovely property at Friar’s Bay and the Admiral Owen home. By the 1880s the rich, famous and powerful had wearied of the stifling summer heat and humidity of Boston, New York and Philadelphia and the railroad provided them with a relatively convenient escape to the coast of Maine and New Brunswick. The group pictured above imagined Campobello both as a profitable tourist mecca and a place their families and friends could summer in comfort. As we will see later there was a conflict between these two objectives.

Tyn-Y-Coed Hotel Campobello built on Friar’s Bay in 1881 by the Campobello Company

The Tyn-Y-Maes built in 1883 to handle the overflow from the adjacent Tyn-Y-Coed

Within a year new owners had built the Tyn-Y-Coed at Friar’s Bay which opened in early July of 1882 although guests found the furniture somewhat lacking. Specially made for the hotel it was at the bottom of the ocean, the consignment having gone to bottom of the Atlantic when the schooner Annie McVicar sank. Still business was so good in the first year that the company built the Tyn-Y-Maes nearby in 1883 to handle the overflow. The two were within walking distance of each other.

The Owen Hotel, the Owen Family home

Some accounts say they also built the Owen House which the new owners advertised as the Hotel Owen. This building was located some distance from the Tyn-y-Coed and Tyn-Y-Maes but the Owen House remains in business as a hotel today and according to the hotel’s ad the hotel was built in 1835. It is possible the Boston magnates made renovations to Admiral Owen’s home in 1881. The room rates for the Tyn-Y-Coed and Hotel Owen were $11-$14 dollars a week, considerably more than hotels in Eastport or St. Andrews. The Algonquin had not yet been built.

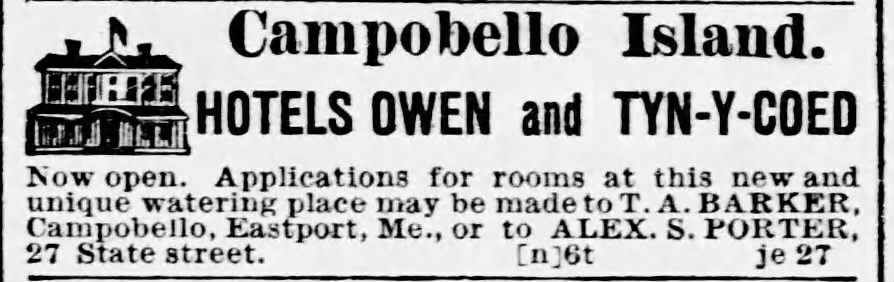

This 1882 ad was in newspapers across the United States and Canada

The Campobello Land Company had a thriving business in those early years. Ads appeared in papers throughout the United States and Canada and guests came from all parts of the United States and Canada but the majority were from New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Montreal.

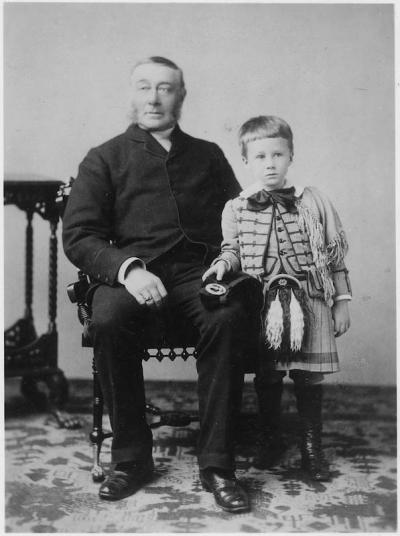

James Roosevelt and his son Franklin were early visitors to the Tyn-Y-Coed

One of the early guests was James Roosevelt and his son Franklin seen above in 1883. They stayed at the Tyn-Y-Coed and were so enamored of Campobello they purchased a cottage lot near the hotel within a year. Their boathouse was on the shore very near the hotel.

The hotels provided many amenities including card rooms, tennis courts, bowling alleys and a nine-hole golf course. Plays and musical entertainment were on offer most days and of course there was the bay with its many charms and diversions.

Consider this from Chanute Kansas Blade:

12 Sept 1890

Fishing here those will fish who never fished before and those who always fish now fish the more as the poet remarks in his casual way. Here anybody can catch fish, and catch very big ones, and catch a great many. Women haul in pollock or cod or salmon as heavy as they can lift, and children of 10 bring home in a boat or a cart a string of fish each one of which is bigger than his captor. It is the greatest fishing resort I ever saw or heard of from a credible witness. Nobody goes fishing and returns empty handed. I went out in a sailboat with four ladies. One did not fish, she sat and raptured and bossed the job. Four lines 150 feet long were kept going by four persons only one of whom had ever caught a fish before. We fished on the top and turn of the tide about an hour and a half. We caught 28 fish, the smallest of which were 7 pounds and the largest 25 pounds. They probably averaged 12 pounds- say 800 pounds of fish, including two cod. Nor was this extraordinary. In fact, it was far below the average mark. We were surrounded by sixty other boats each one having a far better record, for it was managed by an expert, who fished for gain and captured every creature who nibbled. Fishermen often sail out and take one fish a minute for two hours- 3/4 of a ton of food!

The hotels naturally had libraries as reading was a passion of nearly everyone in those days. In 1887 the author Arlo Bates of East Machias wrote what the Times-Democrat of New Orleans described as a “summer novel” set in Campobello. Called “A Lad’s Love” the paper commented “Though slight in substance, the story is bright and cheerful, and will be a pleasant companion of a stray half-hour.”

There were, naturally, tragedies and intrigues at the hotels. A rich American’s wife went missing and her husband hired a team of detectives to track her down. The trail led to the Tyn-Y Coed where she was apparently quite happily waiting tables. She found herself on the next boat to Eastport, the victim of a clearly illegal extradition. A tragedy which could have been much worse occurred when a young man took a group of young ladies from the hotel for a boat trip on the bay. Shooting seagulls he accidently shot himself and the boat was being dragged by the tide into deep waters when saved just in time by a passing fisherman.

As noted above the deep pocket buyers of the island had dual motivations when they built the resort hotels. Naturally they wanted to make money, but they also wanted to provide their friends and families with a beautiful, safe and cool locale to spend the hot summer months. As it turned out mixing Boston Brahmins and paying guests created a somewhat toxic atmosphere. W.A. Croffut describes the problem in the article below. Croffut was an established journalist who wrote for some of the country’s best known newspapers. A veteran of the Civil War, he traveled extensively, wrote poetry and musical scores. Croffut loved Passamaquoddy Bay but not the hospitality onshore. Croffut’s account of his visit to Campobello in 1890 is most interesting and was published not only in the Kansas City News but many other national papers.

Kansas City News and Advocate Topeka 25 October 1890

IN THE QUODDY ISLANDS.

NOT NECESSARY FOR THEIR FISHERMEN TO LIE

Croffut Goes To Campobello- The “Points” of the Winthrop-Sea Mule-Cool Even in August- No Good Hotel. Boston Folks Who Don’t Know How to Enjoy Themselves- Is It Beans That Does It? A Mad Lawyer-Go in Crowd or Not at All.

Our New Brunswick Letter

This Passamaquoddy Bay is a vast and splendid archipelago, bigger and finer than the archipelago of Greece, among whose tempting islands Ulysses got lost. If one had a steamboat at his call he could, I suppose, travel a month here without going the same trip twice.

It is so full of fish that the truth answers very well indeed, and lying about the day’s catch is almost unknown here. If there was as good fishing in every bay and river everywhere I fear that lying would become a lost art.

OUR PET STEAMER.

The great trouble with the region is that it is not easily accessible. Steamboats run occasionally, but they are a tough lot of vehicles. From what I have seen of them I judge that they are the boats that New York long ago got through with and sent to limbo- the refuse boats, so to speak, of the metropolis. Between Bar Harbor (the end of the railroad) and here the “Winthrop” runs; and it is very rough indeed for steady old John Winthrop to have such a jiggling craft named after him. For the first two miles out, I thought she was going to roll over upon us and mash us into the trough of the sea, but she contented herself with cutting up every other kind of dido that is practiced by the Mexican broncho. She indulged in various caprioles. She took the flying jib boom in her teeth, stood upon her hind legs and snorted and pawed the atmosphere. She bucked till we had to seize hold of the pummel, the bellyband, the cropper, and every other part of the harness to keep from soaring into the blue empyrean. She sat down and tried to slide us off behind. But she did not turn summerset. When we walked out through the gangway we smiled and said “thank you” with a good many mental reservations. I foresee the awful doom that awaits the “Winthrop. Some passenger will get so disgustingly sick on some of these passages that he will crawl down into her hold at midnight, bore a two inch auger hole in her bottom, and let the Atlantic Ocean in.

It is cool here. We wear assorted blankets on us at night, after sitting by a wood fire all the evening, and then we get up and eat strawberries for breakfast. Some mornings it is uncomfortably cool, so that we have to pile on all our wraps to keep comfortable if we take a ride across the island to Herring Cove. The roads of Campobello are passably good, so that the summer visitor has his choice of 25 or 30 miles of them. This would be an ideal place in which to spend the two sizzling months, if it were not for one drawback: there are no good hotels for tourists. This, it will be seen, is a monumental drawback. Eastport, situated on a lovely island, facing the cool sea, has not yet shown enterprise enough to build a first-class hotel. And there is not one at Grand Menan-a superb cliff surrounded by seals, whales, and eagles, and blown upon by all the salt winds of heaven. There ought to be fine hotels at both places, and there doubtless will be pretty soon. I hear that St Andrews, at the mouth of the St. Croix, has erected a thoroughly modern and spacious summer resort, but I have not been there and cannot vouch for it.

COOL IN AUGUST

Campobello ought to have a good hotel for summer travelers, but it hasn’t. It has a good house, but it is not for the public. The trouble is that it is owned by a bevy of Bostonians who regard it as their own private preserve and look upon all other guests as intruders. Fugitives from the heats of Manhattan Island may come here and stay a day, a week, or a month they will not only not be spoken to, but they will not be looked at. They may be rich, cultured, high in their professions, but it makes no difference.

The Boston female platoon holds the fort, clustering in dining room, parlor and dancing hall, and persistently ignoring all others as interlopers. Fortunately, I was with a party of five, so that we had abundant resources of our own, and needed not even the civilities of ordinary human life at the hands of others. But while we were there dozens came and speedily went driven away by the rudeness and the sepulchral gloom. A prominent New York lawyer, as he fled, said to me, “I can stand it, but my wife can’t. She’s frozen out. She is treated as if she had broken into a private house. I am merely treated like a confidence man, but I am little in the house.

“These Bostonians are exclusive,” I said, apologetically. “No, “he said, “they are not exclusive. They are merely provincial and boorish.”

“They do not make acquaintances readily,” I suggested. “Perhaps they are a little too conscious of their alleged Puritan ancestry.” “Heavens!” he exclaimed. “It is not acquaintances my wife wants. She has now more than she can manage. It certainly isn’t friends. Nobody makes either friends or acquaintances at such a place as this and nobody ought to. But human recognition every decent person has a right to. The Sioux or Bedouins would concede it to a stranger coming into their wigwams. Even on a transatlantic steamer passengers speak to each other, and it would be intolerable and barbarous if they didn’t. They do not often make friends, of course; there is a tacit rule that persons who speak on a steamer or at a summer resort shall not thereafter know each other except by specific agreement to that effect. The fact is that these Bostonians do not understand the world’s etiquette. They are narrow and ill-bred and have not traveled. They protest too much, they imagine that they will commit themselves to undesirable acquaintances if they allow themselves to be betrayed into word or nod. They are rude and their knowledge of the world’s busy life is limited to Boston Common. So, goodbye. We shall go back to Bar Harbor.

I cornered one of the stockholders of the place and asked him to explain the hostility shown to travelers. “Well,” he frankly said, “to tell the truth, this hotel is regarded as a private summer home, and strangers are not welcomed here. I think the stockholders would actually rather have it all to themselves. They do not expect to make money from the hotel, but from the occasional sale of lots to cottagers.

A BOSTON LADY’S DEPARTURE

“In that case,” I asked, “doesn’t it strike you that it is getting money under false pretenses to advertise the charms of the island and entice people to come here with the impression that they will be treated as guests as at all other hotels in the world “I imagine it is not pleasant to strangers,” he acknowledged.

“The stockholders families form a coterie. They come here and stay all summer. They do not see tourists at all. But they are fond of each other. Observe what a fuss is made when one of them must go before the season closes.” I said I had noticed it.

This letter is written for more than a million readers, and to them I cannot say too much in praise of Campobello Island as a summer resort. It is continuously cool, not one hot day or one warm night from May to October. There are many picturesque drives. Fishing is like fishing in a stocked pond or like hunting steers in the Chicago cattle yards. The excursions presented by the dentate shores and the reaches of the Bay of Fundy are divine. The hotel is admirably kept by a man who has reduced catering to a fine art But, dear readerl don’t go there dependent in the least on human society. Go as you would go to a picnic, or as you would go to a ball in Arkansas where a vendetta prevails go with a crowd big enough to hold its own or else keep away.

W. A. Croffut.

We can only speculate on whether Bostonian noses held continually on high led to the demise of the resort hotels on Campobello but within about ten years the business was going decidedly south. The newspapers still provided lists of the rich and famous who had been guests on the island during the season but by 1900 custom was down and in April 1904 the Bangor Daily reported the Tyn-Y-Coed would not open for the season although the Owen Hotel would continue to operate. The Tyn-Y-Coed never reopened and in 1914 was demolished.

1914 Bangor Daily News

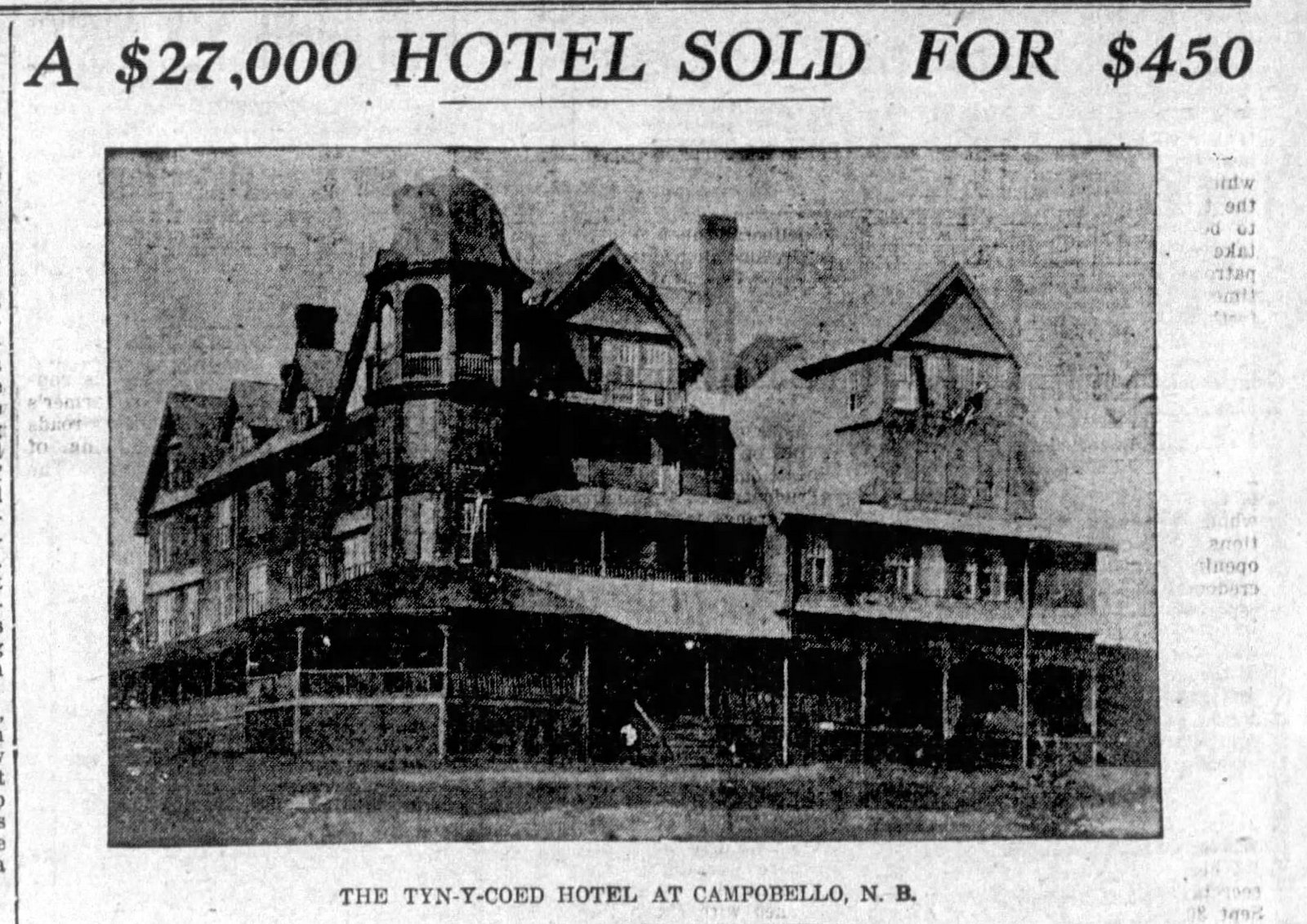

1914 sale of TYN-Y-COED

A $27,000 HOTEL SOLD FOR $450

THE TYN-Y-COED HOTEL AT CAMPOBELLO, N. EASTPORT.

The once famed Canadian hotel located at Campobello Island, New Brunswick, two miles across Passamaquoddy Bay from this city is now being torn down and within a few weeks nothing will remain on the site, for the property was sold at public auction several weeks ago for $450. The successful bidders were John J. Alexander, Harvey Johnson and Horace Mitchell of Campobello who have a crew of men working about the old hotel which for many years attracted many summer visitors from the United States and Canada.

The Tyn-y-coed hotel was built about thirty years ago at a cost of $27,000 and at a time when lumber was considerably cheaper than at the present time, and general laborers were not paid as much, and in later years considerable money was expended about the hotel in making repairs and additions so that the cost figured at more than the above. It can be seen from the amount which the property sold for recently that it had gone Into decay, and there are even some residents on this Dominion Island In the bay who do not figure on the three successful bidders coming in for much profit when the time for removing this structure is figured up, and the pay allowed for the workmen now taking apart all the woodwork that can be of later value. It had been about ten years since the TYN-y-coed was closed to the public and for some years previous it had been considered a losing venture, from the fact that it seemed too far away from the busy cities to draw many tourists for their usually short vacations, although Campobello Island has many charms for the summer folks, and there are a number of handsome cottages on the island that are owned by prominent Americans who come to this spot every season.

The above hotel accommodated about 225 people, and a few years after it was built there was such a rush to tills resort that the Tyn-y-Mae was built only a short distance to the east, where sleeping accommodations were had for nearly as many more, but with the closing of the big hotel, its adjacent bedroom was also closed and has been considerably neglected in recent years so that many repairs and improvements would be necessary before It would be available, excepting for private families.

It can be easily remembered by many Eastporters when the Tyn-y-coed hotel was one of the most popular and largely patronized resorts along the coast, but for some unknown reasons it gradually lost Its grip on the summer folks, cottages were built on the Island not far from the hotel, and after the company had reopened the hotel for a few seasons at a loss it was finally abandoned, and now is being removed from the lot.

The bowling alley and laundry buildings were bought by New York parties who will construct a large bungalow early in the spring which they will have ready for their summer’s visits to this Canadian island. Close to the above property is the large cottage of Assistant Secretary of U.S. Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, the cottage of Mrs. James Roosevelt of Hyde Park. N. and cottage of Major Archer Shea of England who have been regular summer visitors for a number of seasons past.

The Roosevelts stayed on and tourists can still book a room at the Owen which remains open so all was not lost with the demolition of the Tyn-Y-Coed. Campobello remains a remarkably beautiful island. The International Park featuring the Roosevelt cottage attracts thousands of visitors every year.

You may recall that Croffut in describing his trip to Campobello in 1890 on the steamship Winthrop prophesied “I foresee the awful doom that awaits the “Winthrop.” He was spot on.

Pittsfield Eagle June 14 1893

Total Loss of the Winthrop at Eastport, Me.

WAS VALUED AT $125,000

Flames Finish Their Work Despite Efforts of Crew and Fire Department

The Wreck Sinks Six Mile From the City Insured for $75000.

Eastport, Me., June 15. Steamer Winthrop, of the Mallory Steamship line, running between New York and St. John via Bar Harbor and Eastport, arrived here from St. John last evening at 7 o’clock. In a few minutes after being made fast she was found to be on fire, and in spite of every effort of the crew and city fire department, the flames got beyond control and the Fine Ship Was Doomed. Lines were cut and she was pulled out into the harbor by tugs Greenwood and Lubec, and went drifting down around the lower end of the city, a mass of flames. A thick fog set in and hid her from view. The Greenwood and Lubec followed her up and Captain Cousins of the Winthrop requested the Greenwood to hold to the burning steamer and beach her, if possible, but the Lubec claimed the right to hold the Winthrop, and cut the hawse of the Greenwood twice. Then, in the fog and excitement, the Lubec went ashore on Goose Island bar and was obliged to drop the wreck and blow a whistle of distress. The Greenwood sent boats to the Lubec and took off a large number of spectators who had gone aboard to follow the burning steamer. The Lubec soon came off with the rising tide, both steamers returning to Eastport at 10 p. m. Captain Cousins. Chief Engineer Kurst and First Officer Boomer remained near the wreck in a boat and did not return till this morning. The wreck drifted around and sank near Red Island, six miles from this city. The Winthrop was a fine boat of 1.400 tons and has been on this route since 1890. She was built in Bath in 1877, was valued at $120,000 and insured for $75000.

The Winthrop’s captain succeeded in docking his burning ship and safely disembarking his passengers and crew members. By that time the flames had leaped through the deck. The Winthrop’s lines were cast off and a tug towed the burning ship a short distance offshore so that danger from fire to the Eastport waterfront could be averted. The flood tide carried the steamer up around Green’s Point and she burned to the water’s edge off Broad Cove. If one remembers correctly, only one life was lost when a crew member suffered a heart attack.”