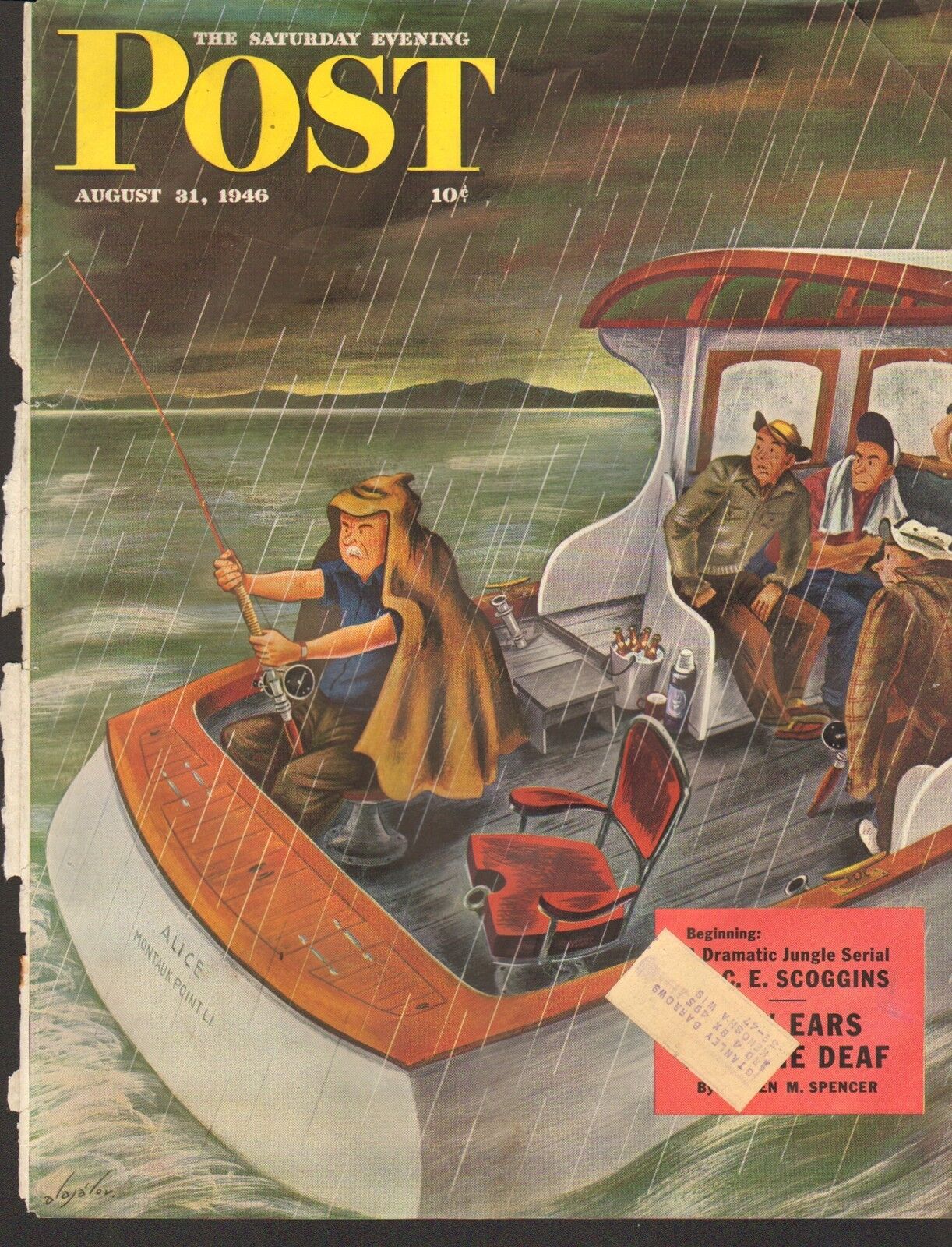

Saturday Evening Post Cover August 31 1946

A member of the Historical Society recently sent us an article from the above issue of the Saturday Evening Post dated August 31, 1946. The article was titled “St.Calaisphen, North America” and

had been clipped from the magazine and saved for posterity. It was found with some old family papers. In 1946 the Saturday Evening Post was the most widely circulated magazine in North America and most subscribers read every word in the magazine including the ads. Over the years hundreds of articles describing the rather unique relationship between Calais and St. Stephen have been published in national newspapers. They usually marvelled at the remarkable sense of community between the towns, the cooperation of fire departments, Calais being the only community in the United States to get its water from a foreign country, Calais borrowing gunpowder from St. Stephen to celebrate the 4th of July when the countries were legally at war and especially the sense that the border between the two towns was, as Mr. Furnas notes, an ‘imaginary border.” The article by Mr. Furnas in the Saturday Evening Post is however exceptionally well researched and written so we decided to share it with you. It is lengthy but well worth the read for those interested in how our international community prospered and thrived even though separated by nationality, a river and some claim language.

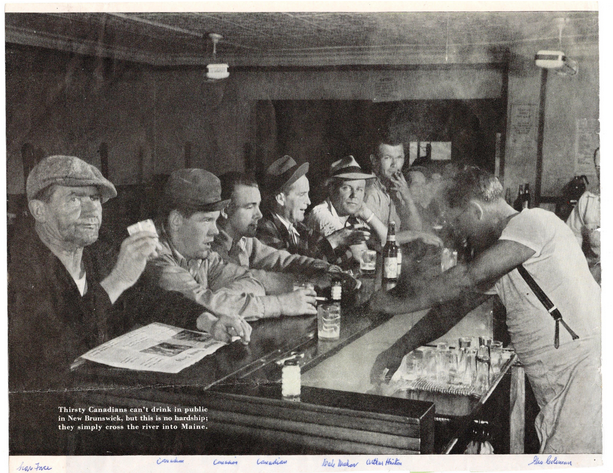

The photograph at the beginning of the article.

Note- the names written under the photo are from the left Scarface, Canadian, Canadian, Canadian , Dale Mahar, Arthur Hinton, George Coleman bartender.We do not know who Scarface was or any of the Canadians. Arthur Hinton drove a truck for Eastern Pulpwood in 1935 and lived on the River Road but married Muriel Tracy and moved, we believe, to Downes Street. Dale Mahar graduated from Calais Academy in 1932, lived on Barker Street and in 1935 was an accountant for the Daly Shoe Company. George Coleman lived in the Union and was a veteran of WW2.

Saturday Evening Post: August 31, 1946

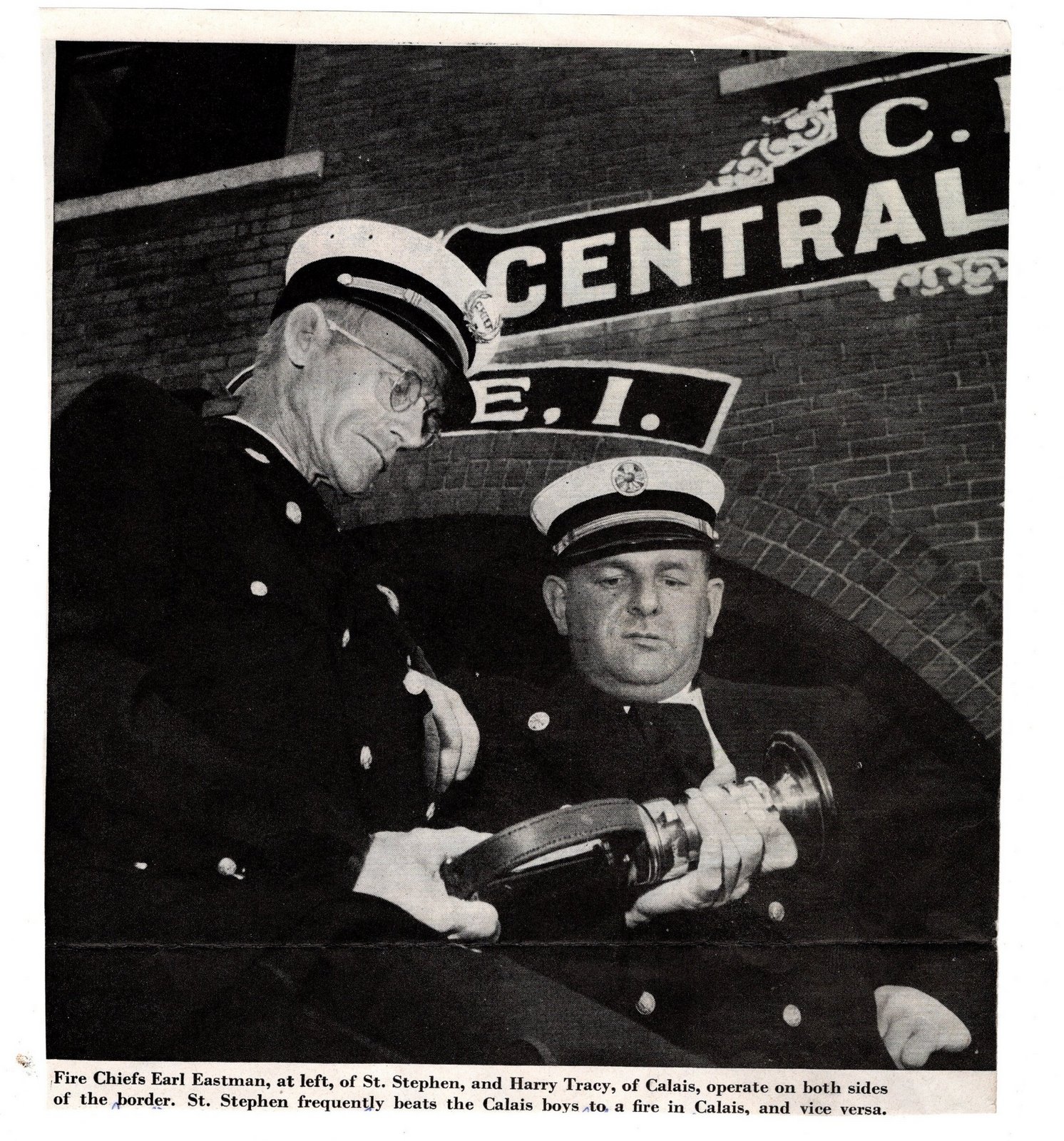

Earl Eastman is a lanky, sober -paced Canadian, a building contractor, and the veteran chief of the paid-volunteer fire department of St. Stephen, New Brunswick, across the St. Croix River from Calais, Maine. When a Calais chimney catches fire, the alarm rousts out not only Calais’ similar paid-volunteer department but also Eastman and his boys. Their big red trucks clang and bellow across the international Ferry Point Bridge with no more ceremony than a hurried wave of the hand to the immigration and customs officials at either end. Every St. Stephen alarm sends Calais’ fire department howling over the bridge in the opposite direction.

From 1946 article

The two outfits compete doughtily in the local fire-department field-day exhibitions. But, if Chief Eastman finds that Chief Harry Tracy, his stocky, ruddy opposite number in Calais, is sick or away, he automatically takes command of the Calais department too-and vice versa. A while back when a Calais fire truck got smashed up in an accident and replacement was slow, St. Stephen lent her sister town a spare truck without hesitation- after all, it would still be fighting St. Stephen fires, whatever side of the river it was housed and manned on.

“We don’t have to worry about committing equipment without allowing for reserves,” says Chief Tracy. “We know St. Stephen will be right there behind us in a matter of seconds.” It has happened, in fact, that St. Stephen has beaten Calais to its own fire-and again vice versa.

Outsiders visiting these two towns sometimes get dizzy from their manifestations of vice versa, you scratch-my-back and. hands-across-the-border. International treaties may say that the United States-Canadian border means business in running up the middle of the channel of the St. Croix. But at low tide-this is the head of navigation-the water practically disappears and, by leaving no channel to mention, neatly symbolizes the relations between the two towns and the official boundary. You could walk across if the bottom weren’t so oozy.

The post offices on either side sell different kinds of stamps, the St. Stephen filling stations sell imperial instead of U. S. gallons of gas. But the Calais post office’s biggest single customer is a St. Stephen firm, and at least one St. Stephen filling station trucks its gas from a Calais supplier to avoid one variety of Canadian tax.

Up the Maine border, where the boundary is a mere imaginary line, relations have always been close back and forth. But here at St. Calaisphen-a name you will not find on any map-people most blithely tangle up their transborder economic and social lives without thinking twice about it.

Many other things besides fire engines cross the hundred-yard Ferry Point Bridge. The husky kid on the bicycle is a Calais Academy basketball forward headed for practice in the gymnasium of the St. Stephen High School, an arrangement made when the academy burned a year ago. Reciprocally, the Calais coach helps train the St. Stephen squad. And not long ago the Calais baseball team, up against an important game with their best pitcher sick, borrowed a winning pitcher from across the river.

Canadian Customs Historical Society collection

The middle-aged lady crossing next is a member of the St. Stephen High School faculty on her way to get a book from the 20,000-volume Calais Library, built on a riverside site contributed by an American with funds that came partly from St. Stephen donors. St. Stephen has no library nor, so long as mutually friendly relations continue-and they are probably good for the next million years-does she need one.

The car rapidly approaching the end of the bridge is waved on, hardly slackening pace. The uniformed Canadian immigration official is well aware that the lady in the back seat is in a highly interesting condition and on her way to have her baby in the Chipman Memorial Hospital in St. Stephen, which has the special maternity wing that doctors recommend and the Calais hospital lacks. Only contagious diseases-which this is not-are barred from the standing arrangement that permits medical patients to go back and forth as freely as necessary.

Chipman Hospital Historical Society collection

A good third of the babies born annually at Chipman are from American mothers. Conversely, a St. Stephen wife occasionally has her baby in Calais to give it what she considers the advantage of dual citizenship, which means unrestricted entry into the States. As an intimate part of life, things medical are specially tangled up hereabouts. The director of the Calais hospital is Canadian-born; two in five of the staff physicians at Chipman are Americans from Calais, and the St. Croix Medical Society, headed by an American, takes in doctors on both sides of the river. Chipman borrows supplies, such as fifty grams of penicillin, from Calais in as neighborly a fashion as a housewife running next door for a cup of sugar, and Calais borrows Chipman’s skingrafting equipment when needed and sends over difficult X-ray cases to take advantage of Chipman’s special X-ray facilities.

“It’s very nice here for American mothers,” says a staff member at Chipman, showing big airy rooms facing the river. “They can lie here recuperating and look over at their own country.”

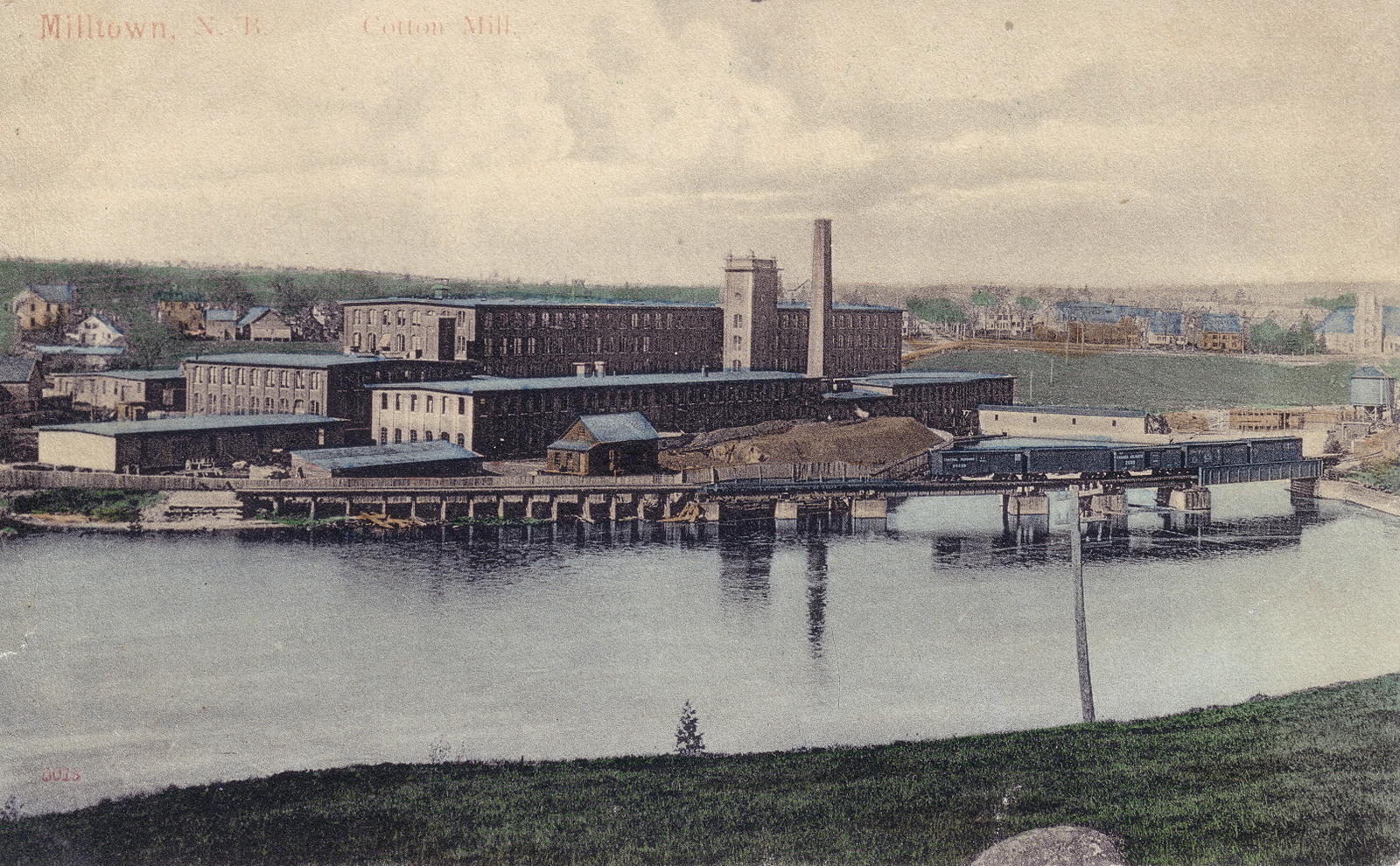

The electric light in the delivery room of both hospitals comes from the same place-the hydro and coal generating plant of the Canadian Cottons rayon mill a mile upriver from the Ferry Point Bridge, which supplies current to both towns. Though the plant proper is in Canada, one of the generators sits across the dam in the States, and the distributing lines make an international loop. Cooking gas for St. Stephen, in reverse, comes from the Calais gas plant.

Ditto, or more so, for the water in the hospital taps. Residents of St. Calaisphen take their water supply big, partly because it is beautiful, soft spring water that never needs chlorine, partly because it ties the two communities together so dramatically. Pumped from a bountiful natural spring northeast of town, the water supplies St. Stephen, crosses to Calais in a pipe under the bridge, goes upriver into Calais’ industrial suburb of Milltown, Maine, then recrosses to Milltown, New Brunswick, which bears a parallel relation to St. Stephen, though the two are separately incorporated. The old Milltown, Maine, pumping plant that once supplied St. Croix River water is kept in stand-by condition so that, in case of emergency, it can send water over to Milltown, New Brunswick, thence to St. Stephen. The eleven thousand or more people on both sides of the border whom this system supplies are proudly aware that even Bob Ripley admits this is the only case in the world of a town’s getting its water from a foreign country.

This warming interdependence goes back at least a hundred and fifty years. In the earliest days of settlement round the falls of the St. Croix, a certain Duncan McColl, one of the thousands of Burgoyne’s army who never went home again, set up as preacher on the left bank, with the sprinkling of right bank settlers making up part of his congregation. The first man ever murdered in Calais-a deputy shot by a counterfeiter operating near a pond ever since called Moneymakers’ Lake was buried in St. Stephen, which then had the only going graveyard in the neighborhood. The precedent is still followed-many a Calais man prefers to be buried in St. Stephen’s pretty cemetery.

All during the War of 1812, which made bloody doings elsewhere along the border around Lake Champlain, at Niagara and Detroit, the Masons, who are still strong round St. Calaisphen, attended lodge back and forth regardless of theoretical belligerency. They say Parson McColl threatened to throw out of his church anybody tactless enough to take the war seriously. And, according to a legend which should be true if it isn’t, Calais celebrated a Fourth of ·July during that war with powder borrowed from St. Stephen’s supply provided by the Canadian government for defense against the Yankees.

As thrifty Scotch-immigrant farmers gradually developed the country back of St. Stephen into its present smiling agricultural state, as fishermen, lumbermen, traders expanded the little settlement on both sides just below the falls, Parson McColl’s transborder cordiality took root and flourished. Until fairly recent times the border there had no immigration guards at all, and Calais and St. Stephen married, played, visited, worshiped and paraded back and forth completely without trammels. Even after immigration laws and procedures stiffened, a process still developing, the old tradition was so strong that nothing either Washington or Ottawa can dream up stands much chance of damaging it.

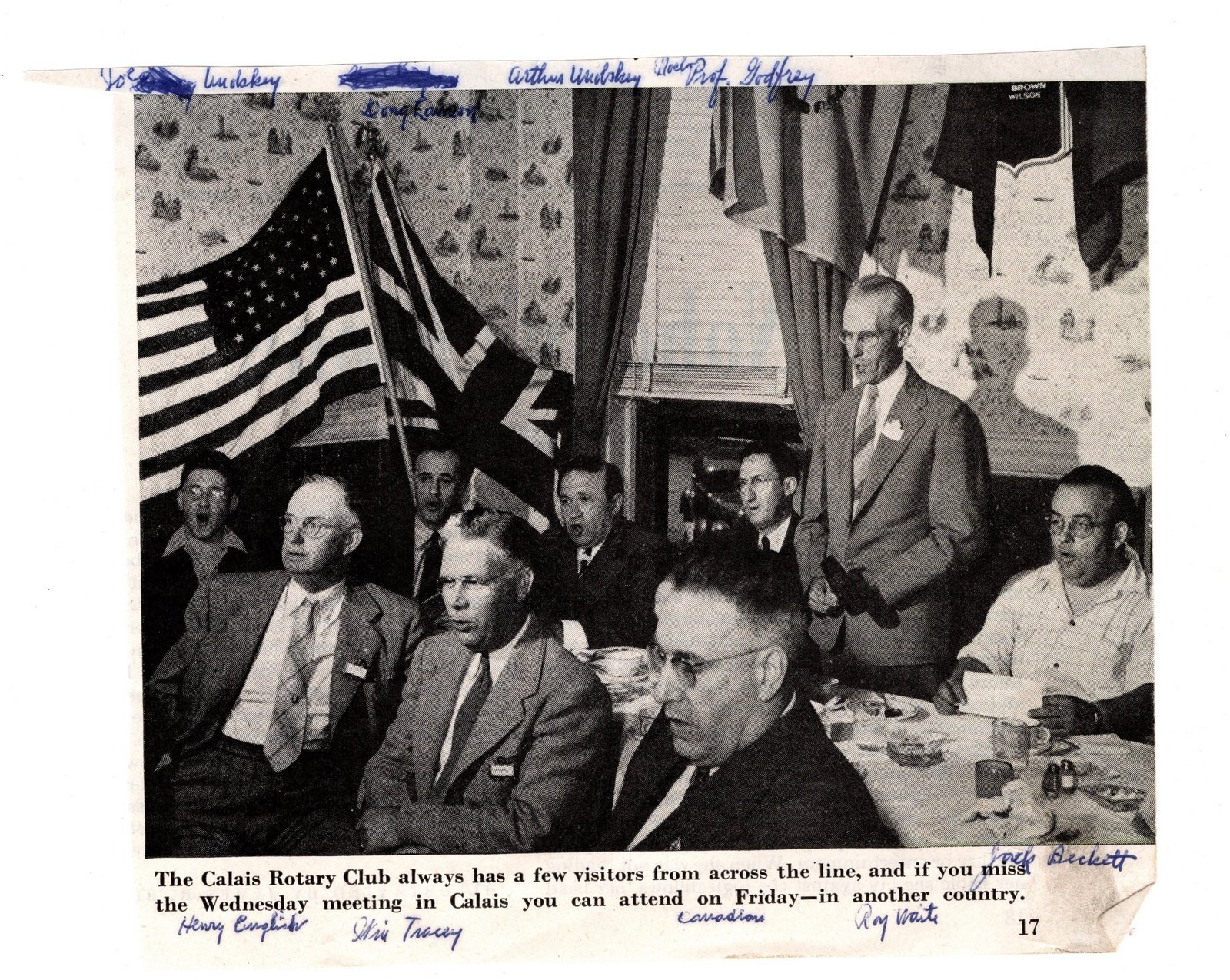

American and Canadian flags displayed at border Rotary meetings-from 1946 article

So Canadian and American flags stand chummily side by side at Rotary meetings in both Calais and St. Stephen, and a Rotarian who misses his Wednesday attendance in Calais can and does make it up by attending Friday across the river. Masons; Odd Fellows, the Washington County, Maine, Chamber of Commerce and the St. Stephen Board of Trade collaborate constantly in very friendly fashion. The St. Croix Club of Calais has shoals of Canadian members. St. Stephen’s Episcopal minister comes over to hold services for Calais’ pastorless Episcopalians. And every occasion for ceremonious celebration means mutual goings-on.

Victoria Day Historical Society photo

On Empire Day Calais blossoms out with American flags and Calais children chant the old rhyme:

The 24th of May is the Queen’s birthday.

If they don’t ·have a holiday, I’ll run away.

The Fourth of July causes St. Stephen duly to break out all its Union Jacks and, when George VI was crowned, St. Stephenites paraded with Calaisians practically all day to the tune of the Stein Song. When song is indicated, St. Calaisphen sings one stanza of My Country, ‘Tis of Thee, followed- or preceded, according to circumstances-by one stanza of God Save the King, which, fortunately, has the same tune.

The band playing the accompaniment usually has about as many musicians from one side as the other. George L. Brist, the American consul in St. Stephen, who has been on that post for over twenty years, has worked out smoothly the formalities necessary for permitting Canadian veterans’ or military organizations to cross the bridge under arms and parade in foreign territory. It is pretty difficult to imagine a German parade in prewar Kehl being attended by gun-toting French war veterans from Strasbourg.

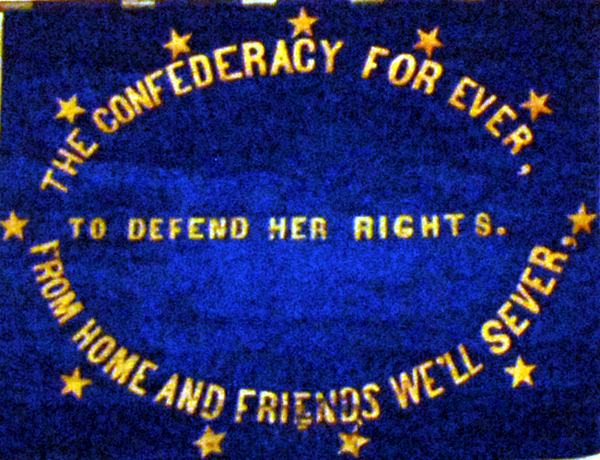

Flag carried by Confederate Officer Collins during Calais bank robbery. Historical Society photo

Naturally there have been and are frictions and inconveniences resulting from that imaginary line in the river bed. During the Civil War, alleged Confederate sympathizers in Canada took the opportunity to raid banks in the States, ostensibly to get funds for “the good cause.” H. E. Lamb, Calais’ local historian, says that 90 per cent of the proceeds probably went for expenses and another 5 per cent for handling charges. The leader of one raiding gang marched into a Calais bank with a gun in one hand and a Confederate flag in the other. But his brother, a Canadian parson who disapproved of his activities, had privately tipped off Calais in very hands-across the border fashion, and the would-be hero was captured with colors still flying. That, it stands to reason, was the only Rebel flag ever captured in New England.

In the post-Civil War Fenian troubles, American Irishmen tried to use Calais as one of several border sally ports for their program of conquering Canada and holding it for ransom against freedom for Ireland. The shindy they kicked up in Calais was even more of a fizzle than those elsewhere, but it did rankle somewhat in St. Stephen minds. Round the same period, according to old-timers, St. Stephen’s young men grew resentful of Calais boys taking brides from among St. Stephen girls. So a lover crossing the old covered bridge to spark his inamorata in Canada might be ambushed and heaved through a bridge window into the river.

That was in the height of the lumber boom, when Calais-built-and-manned brigs and schooners-sometimes a hundred vessels lay at Calais wharves at one time-were taking the local magnificent pine all over the world. Milltowns on both sides owe their names to the scores of sawmills that dressed timber for export. Lumber and seafaring towns are seldom Sunday schools and, if the above is all the trouble that anybody can recall, the situation is more astonishing than ever. Nowadays the only discernible differences between the two places concern whether Sunday-night movies and Sunday baseball are proper .

Nor is either side conscious of difference between the two populations: ·

“Scratch a man from Calais and he’ll bleed Canadian,” says H. E. Lamb. St. Stephenites say they can’t tell a Calais man by dress, walk or habits only- when he speaks do the down Eastern broad a and tendency to twang betray his over-the-bridge origin. And intermarriage is as frequent as ever. Everybody has family t’other side of the river.

War restrictions hit hard. The good old days when the guardians of the bridge, Canadian and American alike, knew everybody in both towns and let them go back and forth as freely as if they were merely crossing the street, disappeared with a thump, and identification papers with photographs became essential and hard to get. Part of the difficulty lay in the fact that Calais’ records burned in a fire long ago.

“I’ve just kissed my grandchildren good-by for the duration,” one elderly Calais resident was heard to say.

Whereas Canadian bills and coins used to make up half of the circulating medium in Calais, no storekeeper ever dreaming of sifting it out of the till for exchange at the bank, the wartime discount on Canadian dollars made that concrete symbol of international symbiosis vanish overnight. Theoretically it was even illegal for a St. Stephenite to cross the bridge to spend money on a Calais movie that he preferred to St. Stephen’s bill for the evening.

Now controls are revoked or slackening, and the two towns are returning to what might most tactfully be called economic mutuality. New Brunswick forbids drinking in public places, whereas Calais has oases, elegantly called cocktail

lounges or beer parlors, so much malt and spirituous liquor gets imported from the States to Canada every Saturday night inside the skins of homing St. Stephenites. The greatest concentration of Calais’ beer parlors is as close to the American end of the bridge as bail-bond offices usually are to courthouses.

The pork chops cooking for supper in a given Calais kitchen very probably came from St. Stephen. Articles costing less than a dollar or dutiable for less than a quarter enter the United States legally free anyway, and somewhat liberal interpretation of that rule obtains. For generations Calais has bought its meat in St. Stephen. American cigarettes, coffee, odd manufactures and women’s clothes have been similarly indispensable to St. Stephen, also for generations. Some tact is necessary: A St. Stephen girl planning to buy a Calais hat merely walks over bareheaded and returns covered. Needing a new dress and preferring American styling, she walks across garbed in her slip with a coat over it. Sometimes an official she knows on the bridge will chivalrously compliment her on her new acquisition as she returns. It’s that simple. Any official in Ottawa or Washington feeling moved to crack down on this sensible relationship dealing strictly in chicken feed should have his head examined. To quote a veteran American immigration official on the spot: “An official at this bridge who followed the book without using common sense would throw both sides of the river into a terrible uproar.”

The Cotton Mill Historical Society photo

Physically, the world’s recent trend toward taking boundaries with suspicious seriousness has left its mark hereabouts. Time was when half of Calais worked in the mills or small factories of St. Stephen, and a good part of St. Stephen had Calais jobs. A small proportion of this cross-employment remains; but for a long time both Canadian and American firms have been officially encouraged to weed out or not replace “foreigners.” These days indispensability must be proved to the hilt before transborder hiring permits can be obtained.

Streetcar number 4 coming across bridge from St Stephen Historical Society photo

Obsolescence has long since suppressed the streetcar· line that used to do a figure eight among St. Stephen, Calais and the two Milltowns, visibly and noisily-binding them together. And this summer the electric-power link is to be cut. Boston interests are installing a 2400-horsepower Diesel plant to take over the Calais load from the Canadian Cottons mill at a cost of some $135,000.

The significance of such changes is not great. The two towns are not easily or lightly disentangled. The country back of St. Stephen trucks its Christmas-tree crop to Calais for loading on the Maine. Central; New Brunswick blueberries are canned in Calais; New Brunswick farmers get crucial cash from pulpwood cut for transborder American mills. Calais also depends considerably on St. Stephen’s hinterland for its winter firewood. After all, it wasn’t far from here where an oldtime sawmill was built smack on the border, the saw on the Canadian side, the planer on the American side, because rough lumber came in free of duty while finished lumber had to pay.

For an old community is likely to be sot in its ways, and this place is proud of its great age. Within Calais town limits is St. Croix Island down river, where Champlain and de Monts set up a French colony in 1604, a white settlement in the territory of the original thirteen states three years before Jamestown. With the down-Easter’s standard attitude toward Massachusetts and all its works, H. E. Lamb has installed in the Calais Library a bit of brick from the remains of the French buildings with the defiant inscription:

“This brick did NOT come over in the Mayflower. It was in Calais when the Mayflower came over.”

Calais once asked the honor of sending the late President Roosevelt a Christmas tree from St. Croix Island, where the first Christmas in the territory of the thirteen states was probably celebrated. When Mr. Roosevelt expressed some doubts as to this being the right island, Mr. Lamb showered down with a regular avalanche of authorities to prove it. He can also prove it was the first place in the western hemisphere where ice skating took place, for the French brought skates along.

Woe betide the pedantic outsider who tries to call this town “Callay,” French-style. It was christened after the historic French channel port, which politely sent its sister town a handsome and handsomely acknowledged present in 1935, but its name is “Callus,” as in chiropody, and that’s that. After all, says Calais, Maine, the residents of Paris, Maine, and Paris, Kentucky, wouldn’t tolerate their towns being called “Paree.”

In Champlain’s time, of course, both sides of the beautiful St. Croix looked like the same country. He would never recognize the neighborhood now, but one can still stand outside the office of the St. Croix Courier in St. Stephen at low tide and look across at Calais and be unable to believe it isn’t the same community. Incidentally, the column of Calais news usually features on the Courier’s front page, and, of its 5000 circulation, about 640 copies go to the States.

The whole thing really puts blood and bones into the words on the bronze plaque that the Kiwanis Club has fixed at the boundary mark on the Ferry Point Bridge:

” This unfortified boundary line between the Dominion of Canada and the United States of America should quicken the remembrance of the more than century old friendship between these countries, a lesson of peace to all nations.”