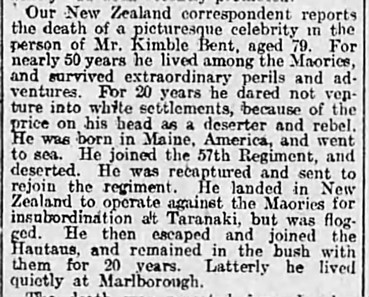

Photograph of Kimball Bent of Eastport

Excerpt from Monday’s Warriors by New Zealand author Maurice Shadbolt, 1992:

Between one luckless general and the next there is a fleck of fable in history’s eye called Kimball Bent.

What a fleck and what a fable! Frontier tales don’t come much wilder or woolier than this rollicking, riveting story of Kimball Bent, born in Eastport, State of Maine, and dragooned into Her Majesty’s army in the middle of the last century. Sent off to subdue the restless Māori in distant New Zealand, Bent finds himself at the wrong end of too many courts-martial and deserts his regiment, becoming the unlikely hero and chief strategist of a Māori band that fights the British to a standstill in what proves to be the bloodiest and most terrifying of the colonial wars.

Most remarkable is that this story is true. Titokowaru and his fierce and feuding lieutenants did humble the English armies that had been sent to snatch their land, and they were led by this slightly befuddled Yankee, who was fighting (and mostly winning) the American revolution all over on the far side of the globe.

And Bent lives on in New Zealand, where parents still caution their children not to go alone into the woods or “you’ll be caught by Kimball Bent.”

Kimball Bent—his first name is often spelled Kimble in newspaper accounts—was born to Waterman and Eliza Bent on August 24, 1837 in Eastport, not Calais as one account contends. His mother Eliza was not of “the Musqua Tribe of Indians whose villages stood on the banks of the St. Croix River” as claimed by Bent’s New Zealand friend James Cowan in a 1911 book titled The Adventures of Kimble Bent. In fact, there is a good deal of confusion about Bent’s early life before he joined the British Army in 1860 and not a little fiction about his life thereafter. The most accurate account of the life of Kimball Bent may well be contained in the renowned New Zealand author Maurice Shadbolt’s fictional work quoted above. Shadbolt actually took the trouble to pay an extended visit to Eastport when researching his 1992 book about Bent.

As to Bent’s true origins, the most credible source is Wayne Wilcox, noted Eastport historian who has written extensively on Bent. According to Wilcox, the Nova Scotia and Eastport records establish that Bent’s father, Waterman Bent, was born in Nova Scotia in 1808 and married Eliza (Reynolds) Bagley on October 23, 1834 in Eastport. She was not a Passamaquoddy and was likely from Dennysville. It may well be that Kimball found it convenient, after deserting to the Māoris, to misrepresent his heritage to the tribe who were, for good reason, hostile to the white man.

Waterman Bent worked at C. S. Huston shipyard in Eastport, and the family lived on High Street near the corner of Battery and Spruce Streets. The Bent house is shown on the 1861 map of Eastport and it was occupied by Bent’s parents and six brothers and sisters. Kimball was the middle child.

According to an article in the Eastport Sentinel of March 14, 1917 titled “Former Resident of Eastport Lived Among the Māoris”:

Kimball was a wild and unmanageable child who was constantly getting into trouble said Benjamin Harris of Eastport, a cousin, who grew up with Kimball and knew him well. Kimball’s wild ways led him into mischief.

Although Kimball’s father had steady employment in the Eastport shipyards, Kimball was not, it seems, interested in following his father’s example.

In an article published some years ago in the St. Croix Courier, Wilcox wrote:

He ran away sometime after 1850 to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia where his father had relatives. Kimball stayed in Yarmouth for a time but shipped out on a brig to Ireland sometime before 1859. From his own account Kimball lived a rough life and was penniless through drinking. At age 22 he enlisted as a Private, # 429, in the 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot on Oct. 18, 1859 in Liverpool, England.

“Taking the King’s shilling,” as enlisting in the British Army was then called, was one of Bent’s poorer decisions although he would soon make worse. He found life in the British army intolerable, and he was not long slipping into the hold of a Yankee windjammer in Cork bound for New York. Two days out of Cork a storm disabled the ship. Although the crew was saved by a German vessel just two hours before the windjammer went to the bottom, the German vessel was bound not for the U.S. but for Glasgow whereupon landing in British territory Bent was promptly arrested as a deserter and imprisoned for 90 days. Upon his release he was back in the Army, the 57th Regiment of Foot, which shipped out to India where the heat was oppressive, the duty boring—and Bent almost certainly did not make the best of the situation. By all indications he was not a good soldier. He was described by a sergeant in the unit as “a man repeatedly punished for acts of petty thievery and drunkenness.”

In March of 1861 the 57th was ordered to New Zealand where the English were running into a spot of trouble. One cynic summed up the situation as follows:

This was in the ‘60s and the New Zealand savages were just then displaying an extraordinary and unaccountable tenacity in their endeavor to cling to the land of their ancestors of a thousand years. As one writer of the times somewhat naively says, “The natives entertained the mad notion of Maoriland for the Maoris.” Plainly, then, it was necessary to “civilize” them after the long-established and generally-approved fashion. Britain was now engaged with this task, finding it, as in the case with the Boers some years after, not quite so easy as anticipated.

It was not too long before Bent was in trouble with the civil authorities in New Zealand. Charged with theft of watches from both a sergeant and a private in his unit he was remanded for trial, convicted and sentenced to a lengthy jail sentence.

From the Wanganui Chronicle June 5, 1862, page 3:

Regina by Thos. Trayner and Jas Beasley v Kimble Bent private H.M. 57th. Regt. The defendant was accused of having stolen a watch belonging to Sergt. Trayner worth £7, which he sold to Mr. Harding, Storekeeper to whom he owed 4s. 2d. [four shillings, two pence] for £1 and of having stolen from Jas. Beasley private in 57th Regiment another watch which was taken from him. Prisoner was committed to trial at the next Criminal Sittings of the Supreme Court Wellington.

From The Wellington Independent, Wellington, New Zealand, 10 December 1863:

Bent escaped from jail but was soon recaptured and was returned to his unit in 1864 where he was not long getting into more trouble. A sergeant ordered Bent and a number of other men to cut firewood on a rainy day, to which Bent replied that it was too cold and wet and “this is no day to send a man out cutting wood. The officers stay in their tents laughing at us fellows out in the rain. We’re treated like a set of blessed dogs.” When asked if he refused to go, he replied “No, I won’t go so you can do what you like about it.” Colonel Hassard of the 57th Regt. ordered Bent be given 50 lashes, a severe punishment even when reduced later to 25. Bent is later claimed to have killed the Colonel in battle. A sympathetic officer smuggled Bent a bottle of liquor and a six pence coin to clamp between his teeth just before the sentence was carried out, but this did little to relieve his pain and embarrassment. The punishment was administered before the entire unit. Bent was to serve several months in the Wellington jail before being transferred back to his unit.

When he returned to his unit he was determined to desert to the enemy.

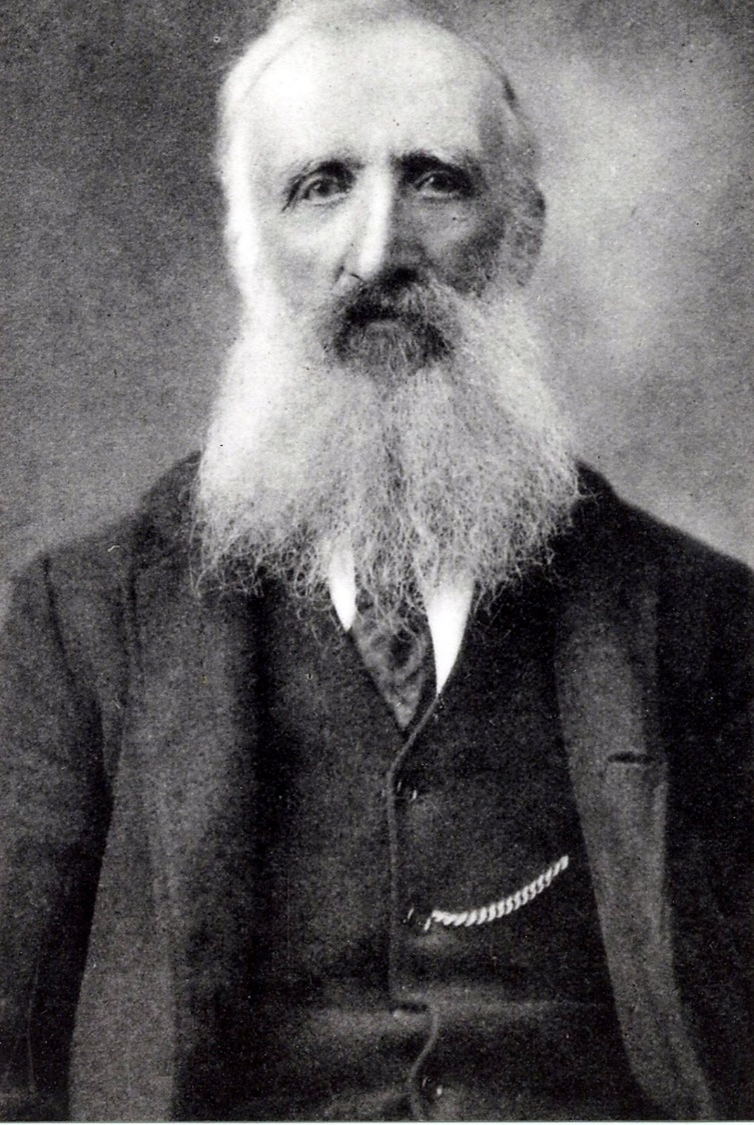

THE WAR IN NEW ZEALAND: THE 57TH REGIMENT TAKING A MAORI REDOUBT ON THE KATIKARA RIVER, TAKAKAKI

Bent’s unit fought the Māori in the heavy jungle and mountains of New Zealand.

Bent’s unit was fighting the Māori in the Taranaki region of New Zealand which was dominated by a mountain of the same name. Described as “Lonely as God and white as a winter’s morn” the mountain dominated the battlefield. The Māori in the region known as Hauhaus were fanatically hostile to whites, deeply mystical in temperament and brave beyond measure. Still when on June 12, 1865, Bent walked away from his camp past an inattentive guard and across the lines to Hauhau territory, he was at peace with his decision. In fact, when some friends in his unit learned of his plans and told him he would certainly be killed by the Māori he replied, “I can’t be worse off with the Māori than I am here. If they do tomahawk me, it will end my troubles. I don’t very much care.”

Bent crossed the lines into enemy territory and was soon confronted by a well-armed Māori scout on horseback. Not only was Bent not killed but the scout advised him to go back to his people. Bent refused and was taken by the scout to the Māori village. Bent did not then realize his good fortune: the scout was Tito te Hanataua, a chief of high standing in the tribe and a brilliant military leader. Bent lived under his protection for many years.

Bent’s life among the Māori was hard and often frightening. He said he was “worked like a dog.” As a “Paheka” Māori, the name given those who were not natives, his status was that of a slave. Further, the younger warriors disliked Bent and if given the opportunity to surreptitiously murder him, they would have certainly done so. Even after he had lived with the tribe for many years there were attempts on his life.

Only after several months did he gain the trust of the tribe who initially suspected his loyalties and feared he might try to return to the British and divulge the Hauhau’s positions and military strategy. Other deserters who attempted to return to the British were caught and summarily executed by the tribe.

There was little chance Bent would defect. A substantial reward was offered for his capture and the British had every intention of hanging him should he fall into their hands. This was especially true after, it was alleged, he had killed Colonel Hassard, the officer who had ordered the 25 lashes, in a battle. The New Zealand papers regularly reported on Bent’s depredations against the British forces. He was said to have been seen fighting alongside the Māori at many of the crucial battles of the war, and in some newspaper reports was claimed to be the military strategist responsible for the many British defeats. This is questionable as the Māori chiefs were acknowledged to be brilliant strategists, far superior to their counterparts in the British Army and would hardly have taken military advice from Bent who had shown a complete immunity to military discipline. Further, his military experience consisted primarily of confinement in jail or the stockade. In the end it was superior British firepower and perhaps the mysticism of the Māori that led to the Māori defeat. Before battle a ceremony was held during which chants, spells and incantations were intoned by the Māori holy men which were said to protect the warriors from British bullets. Many brave Māori fighters needlessly died as a result.

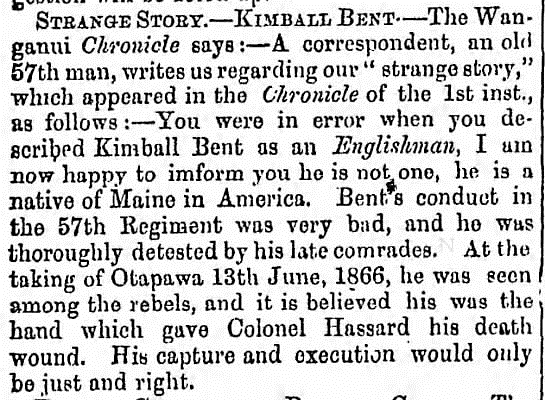

Many accounts appeared in the New Zealand newspapers over the years describing Bent’s traitorous behavior and depredations against his countrymen . . .

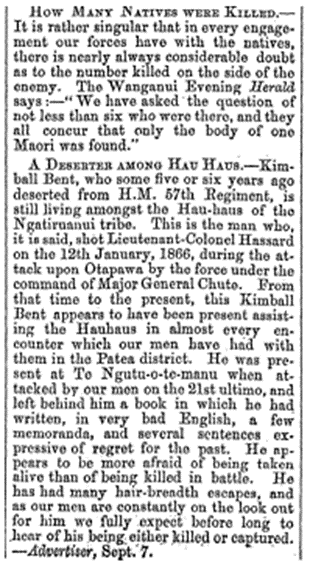

From The Hawke’s Bay Herald, Napier, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand, 19 September 1868:

A DESERTER AMONG HAU HAUS.–Kimball Bent, who some five or six years ago deserted from H.M. 57th Regiment, is still living amongst the Han-haus of the Ngatiruanui tribe. This is the man who, it is said, shot Lieutenant-Colonel Hassard on the 12th January, 1866, during the attack upon Otapawa by the force under the command of Major General Chute. From that time to the present, this Kimball Bent appears to have been present assisting the Hauhaus in almost every encounter which our men have had with them in the Patea district. He was present at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu when attacked by our men on the 21st ultimo, and left behind him a book in which he had written, in very bad English, a few memoranda, and several sentences expressive of regret for the past. He appears to be more afraid of being taken alive than of being killed in battle. He has had many hair-breadth escapes, and as our men are constantly on the look out for him we fully expect before long to hear of his being either killed or captured.

***

From The Hawke’s Bay Herald, Napier, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand, 19 September 1868:

Report of Bent fighting alongside the Māori claims Bent killed Colonel Hassard.

Despite the reports, Bent claimed he never participated in any military action against the British, and Bent’s version is probably far closer to the truth. He did assist the Māori as an armorer, repairing weapons and manufacturing ammunition from captured British ordinance but Bent was not a warrior by temperament, and he feared capture and hanging.

He did however gain the respect of the Māori and had three wives during his time with the tribe and fathered at least two children. His first wife was imposed on him by Tito, his captor, as a favor to the chief in another village. The marriage was very much against his will although he dared not express it; but the union did not last and he later married by choice a young Māori woman who, to his great sorrow, died soon after giving birth to a child who also died. His third wife, Te Karangi Punangaiti, bore him a daughter Maraea who lived until 1940.

The war ended in the late 1860s, and although Bent continued to live with the tribe he began to have more contact with the New Zealand white community especially after the reward for capture was withdrawn by the British. In 1880 New Zealand’s Otago Daily Times reported . . .

Bent was no longer an outlaw.

By 1880 reporters and aspiring novelists were beating a rather steady path to Kimball’s jungle retreats, and lengthy interviews were obtained. He remained a subject of intense interest to New Zealanders, and in 1903 the British officials induced Bent to come to the capital Wellington to be interviewed and photographed. This photograph is the only known photo of Bent and was provided to us by Wayne Wilcox, who went to great lengths to obtain it.

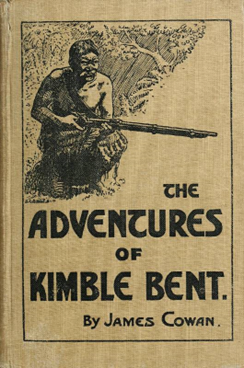

While Bent was in Wellington, he met the author James Cowan and maintained a friendly relationship with Cowan for several years. In 1911 Cowan wrote the book The Adventures of Kimble Bent which is a fascinating read and can be obtained on Amazon Books. Over the years many accounts of Bent’s life have appeared in newspapers in the U.S. In 1992 Maurice Shadbolt, a noted New Zealand writer, wrote the fictionalized account of Bent’s life noted above which Wayne Wilcox endorses as, although fiction, the most accurate account of the life of Kimball Bent. It too can be obtained on Amazon Books. A movie was also in the works after Shadbolt’s 1992 book but never materialized.

Kimball Bent died on June 16, 1916. At the time he was living near the small New Zealand community of Marlborough so perhaps he did finally leave the bush in his old age.

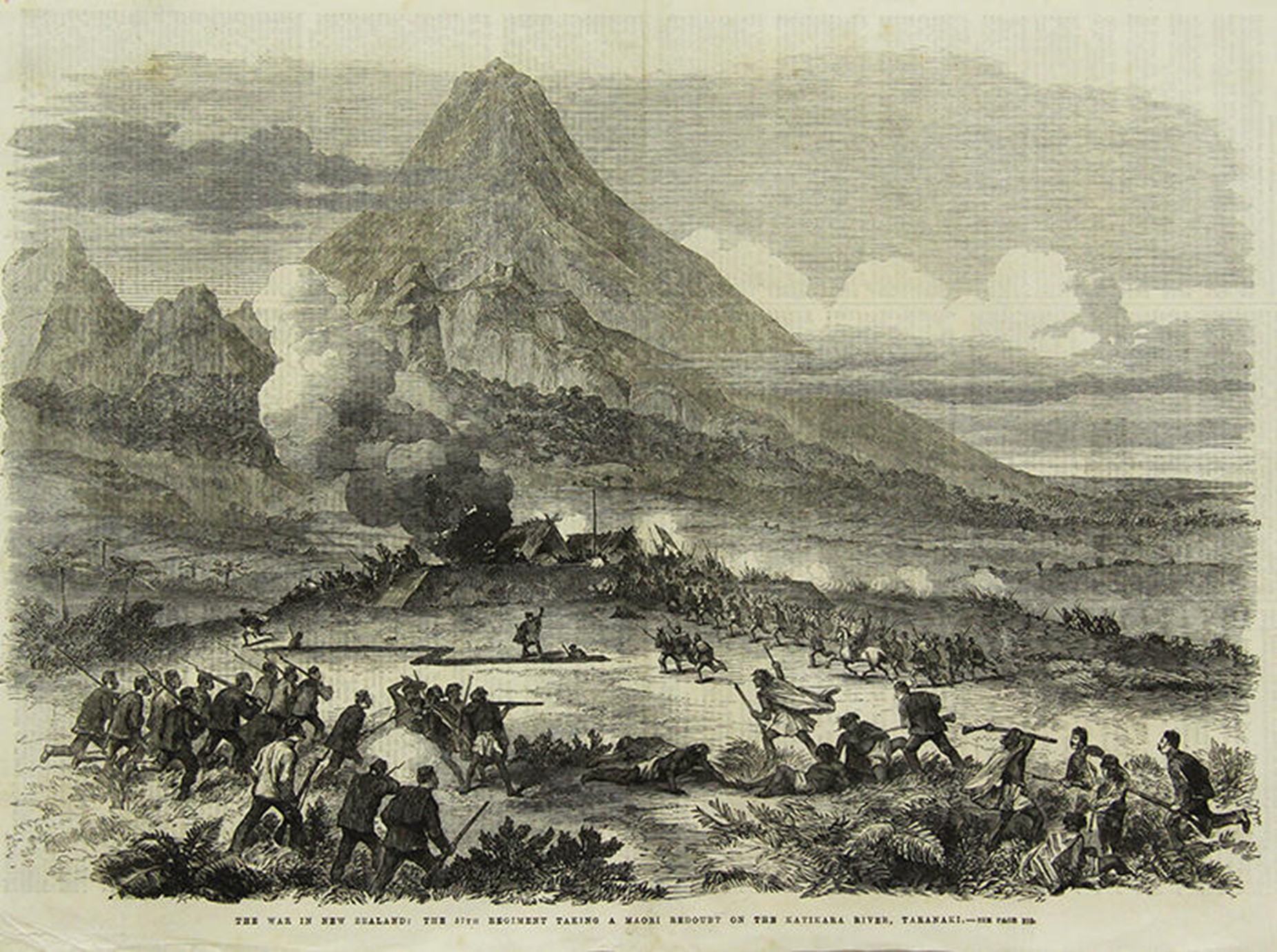

From The Age, Melbourne, Australia, 12 June 1916:

Our New Zealand correspondent reports the death of a picturesque celebrity in the person of Mr. Kimble Bent, aged 79. For nearly 50 years he lived among the Maories, and survived extraordinary perils and adventures. For 20 years he dared not venture into white settlements, because of the price on his head as a deserter and rebel. He was born in Maine, America, and went to sea. He joined the 57th Regiment, and deserted. He was recaptured and sent to rejoin the regiment. He landed m New Zealand to operate against the Maories for insubordination at Taranaki, but was flogged. He then escaped and joined the Hautaus, and remained in the bush with them for 20 years. Latterly he lived quietly at Marlborough.

The writer Cowan, who knew him best, summarized Bent’s life before his death in his 1911 book:

And so the tale of “Tu-nui-a-moa” is told, and we take our leave of the old pakeha- Maori- Kimble Bent, sailor, soldier, outlaw, Hauhau slave, cartridge-maker, pa-builder, canoe-carver, medicine-man, and what not-sitting smoking his pipe in the midst of his Māori friends. He is still living with the natives; working in their food-gardens, fishing with them, house-building for them. A grey old man, of mild and quiet eye, who might easily be taken for some highly respectable shopkeeper who had spent all his life in city bounds. Yet no man probably has lived a wilder life, using the term in the sense of an intimate acquaintance with primeval, passionate savagery, and with the ever-near face of death. He is the sole living white eye-witness of the secret Hauhau war-rites; the only white man who has survived to tell of those terrible deeds in the bush, to tell the story of the last Taranaki war from the inner side-the Māori side.

Bent has reached the age of seventy-three; and now the old man’s thoughts go to his boyhood’s home in the far-off State of Maine, and he sometimes expresses a wish to reach his homeland again. “If I could only get a berth on some American sailing-vessel bound for New York or Boston, I’d even now try to work my passage home,” he says. “I’d like to die in my mother’s land.” But that can never be. He is forever beyond the pale; and he will die as he has lived, a pakeha-Māori.

We do wish he had gotten “a berth on some American sailing ship bound for New York” and lived his last days in Eastport. The tales and true stories he would have told the locals as he sat on the waterfront smoking his pipe would have been entertaining indeed.

Addendum: This 1878 letter from Kimble Bent or Tama Tana, his native name, was written to a New Zealand newspaper to inquire about the possibility of his return to the “white community”.