In an earlier article we covered a 1895 “Letter From Maine” written by HMT, no other identifying information, which described for the folks in his hometown of Shepherdstown West Virginia HMT’s trip from Shepherdstown West Virginia to Calais and his observations of Downeast Maine. In that letter HMT promised another letter which he did, in fact, write a couple of months later. We will now share this second letter which contain some additional observations of Downeast Maine and New Brunswick and thanks to our intrepid researchers Sharon Howland and Terry Allen, we now know a good deal more about HMT.

HMT was, in fact, Harry Matthews Turner of Shepherdstown West Virginia and as noted last week he came to Maine to take up his post in Calais as an immigration inspector for Uncle Sam. He was born in 1858 and married Rose Snyder, two years his junior who is always referred to in the Shepherdstown paper as Mrs. HMT. She lived her entire life in Shepherdstown but he spent over 20 years living with Northerners, for several years in New Brunswick at St. John New Brunswick and Yarmouth Nova Scotia. When he left St John in 1901 the St. John Daily Telegraph wrote:

While his many friends will be glad to learn that Mr. Turner’s value has been recognized by his government, they will unite in a feeling of deep regret that necessitates his removal from Saint John. He has been one of our “oor ain folk” and during the past six years has endeared himself to the traveling public and the citizens of this community by his unfailing courtesy and good fellowship.

We believe he retired from a posting in Yarmouth Nova Scotia around 1920, returning to Shepherdstown where he died November 30, 1927. His wife Rose died March 9, 1935. They are buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Shepherdstown.

ON THE BORDER LAND. Calais, Maine. April 1, 1895. Shepherdstown Editor Register

As intimated in my letter published a few weeks since, I will try to give my second impression of Calais and the region round about, taking courage from the fact that none of the readers of the Register are near enough to me to express, by means of ancient eggs or otherwise, disapproval of a humble effort to entertain them. I have always thought that persons should be very careful how they write of cities within whose gates they are strangers, and as I have been in this to me a strange land but a short time, it is not likely I shall get every detail exact, however hard I may try to do so.

It has been stated that New Englanders have occasionally gone South, either for pleasure or profit, remained a few months, and impressed with the cruelty of the “color line,” returned to their native heath to lecture knowingly upon the “race problem.” However, I shall not with my limited knowledge attempt to solve any momentous problems, either social or political, that may be confronting the good people of New England but shall content myself by writing of some of the things that have caught my eye while on the border land. I write whereas or preface in order that if perchance this letter should, like the proverbial chicken, come home to roost amid the pine branches of Maine, or in plainer words fall into the hands of any of the good people of Calais, it may serve somewhat as an apology for any mistakes it may contain.

To begin, this is a section of the United States and Canada that is interesting to the stranger in many respects. As Shepherdstown and other places in the Shenandoah Valley are of interest to the stranger on account of their being in that section where so many incidents occurred during the late war, so is this locality of interest on account of the many things that took place during the early history of the American Republic. More history has been made along this border from St. John to Quebec by the Americans, British, French and Indians than has ever been recorded, and numerous have been the warriors who have fought on the banks of the St. Croix before the white men’s vessels loaded at the wharfs of Calais and spread their sails to join the fleet of nations upon what Virgil called “the white-winged sea.”

Harvesting potatoes 1930s, not much had changed since 1895

Having been ordered temporarily to Vanceboro, a small border town on the west branch of the St. Croix, about 40 miles from here I had an opportunity while on the Canadian Pacific Railroad of seeing some of the farming lands belonging to the province of New Brunswick.

In all that part of Canada upon which my eyes have rested I have not seen a spot which seemed to me fertile enough on which one inclined to scold could raise even a disturbance, and on this account, I have thought that here good homes could be secured for some of the poor, hen-pecked husbands of Shepherdstown. I am told, though, that somewhere back over the ridges, this side of the North Pole, good farming lands abound. This portion of Maine is not a farming but a lumbering and manufacturing locality, although large crops of potatoes are grown in this, Washington county and Aroostook, the large county west of this, is one of the largest potato-growing districts in the world. I am told that the annual yield of potatoes in Aroostook County is about 8,000,000 bushels, and that from three stations alone in that county 3,500 cars were loaded and shipped to market in one season. The yield per acre is often 300 bushels of merchantable and 75 bushels of small potatoes. The latter are consumed by the numerous starch factories located in that region.

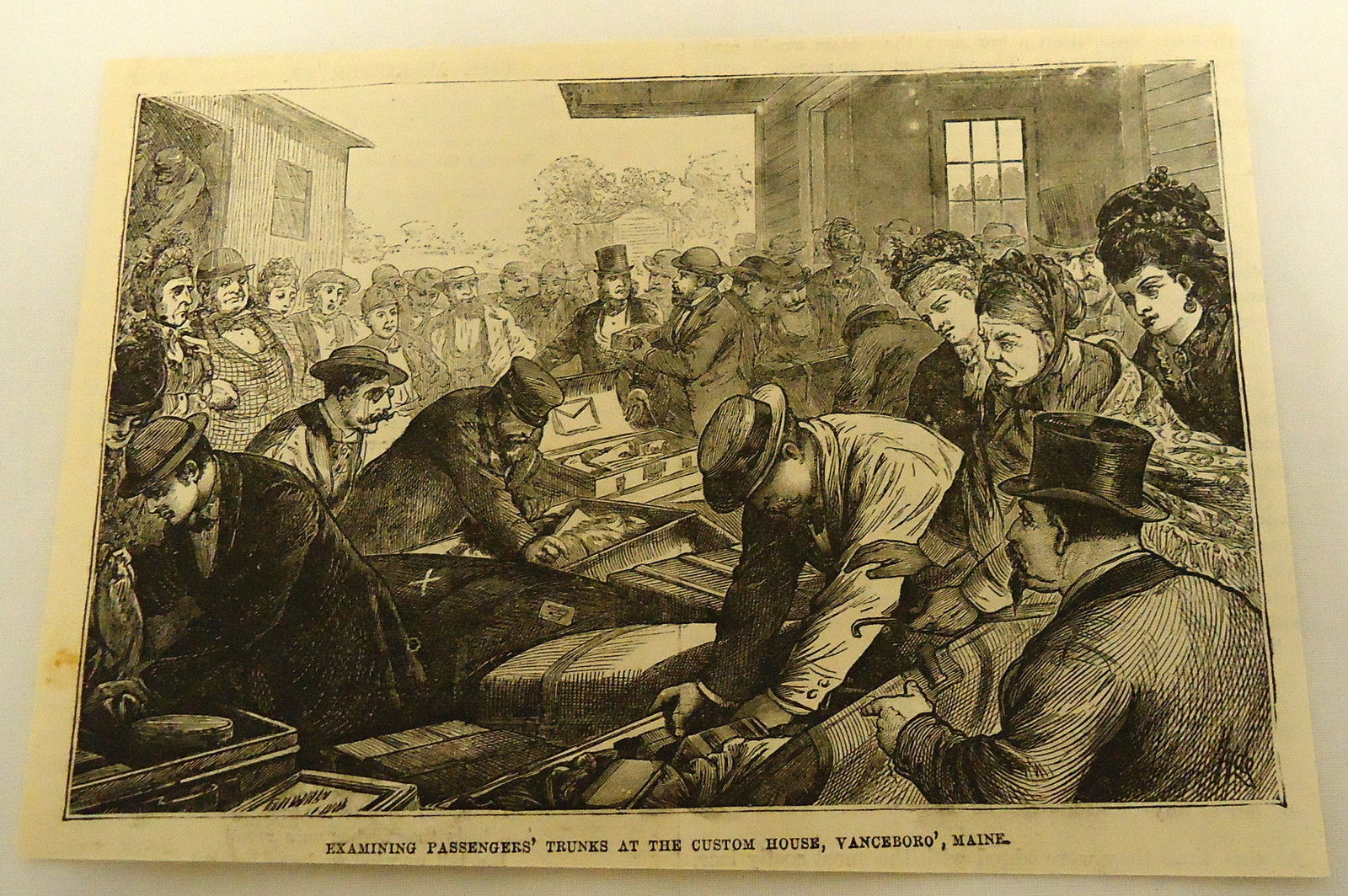

From 1890s national magazine, Vanceboro was an major port of entry in 1891

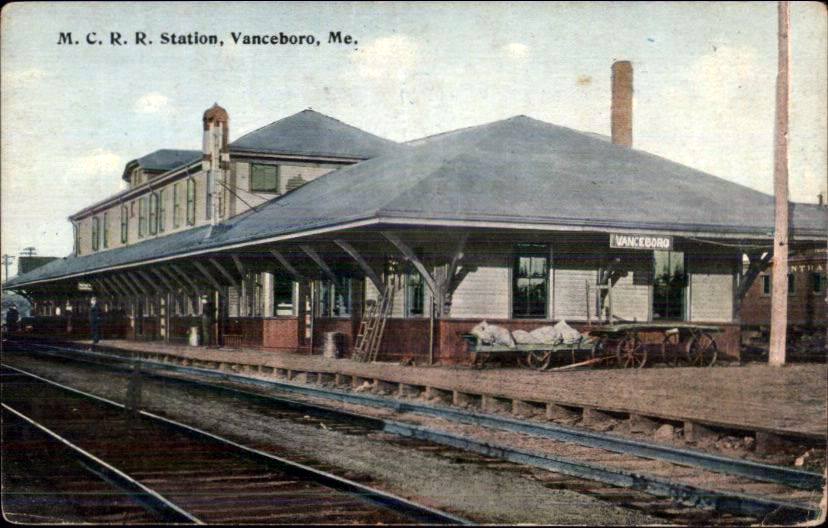

Vanceboro Railroad Station

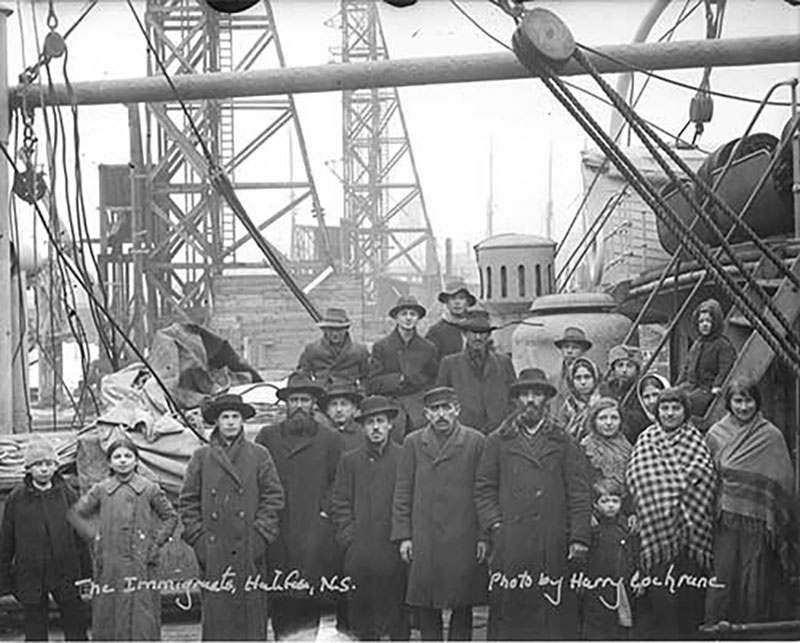

Turner is a bit unfair to the immigrants he processed at Vanceboro. They

had just endured a brutal sea journey, probably in steerage and could not be expected to look their best.

Vanceboro, being upon the Maine Central and Canadian Pacific Railroads, has probably more immigrants passing through it than any other point on the Canadian border. These immigrants are from Nova Scotia and other provinces of the Dominion, and many come from European ports, land at Halifax, and then of course find their way into the States. The United States Government has a commissioner of immigration at Halifax, who notifies the inspectors of any violation of the laws that are likely to occur in their respective localities on the border. Some of these immigrants are capable of making good citizens, but some are not. I had promised to send some of these female immigrants down to Shepherdstown for wives for the widowers and bachelors, but when I saw their grimy condition and heard them speak in answering questions, I concluded to let the boys remain in single blessedness. The immigrants are rigidly examined as to their age. nationality, occupation or calling, whether they are under contract to perform labor in the United States, whether they are likely to become paupers. now much money they have, etc. If after this examination the inspector is satisfied that the immigrant is not of the classes excluded by law he or she is admitted, but if they are of the excluded classes they are, by the train or vessel by which they came, sent back over the border to the care and keeping of an old lady called Mrs. Victoria.

The Cotton Mill in Milltown N.B. was once the largest in the world

I stated in my first letter that Calais was not a village. There are more industries located in Calais and St. Stephens and connected with these cities than I knew of when I first wrote. In St. Stephens, on the Canadian side, a large cotton mill, employing about 6OO persons, is running; the largest candy factory in Canada is in operation; an axe factory, two grist mills and other industries, such as lumber mills, etc. employ many people. In Calais there are in operation eight lumber mills, employing 300 hands; a shoe factory employing 250 persons; a leather factory with 60 employed; an establishment where wool is pulled from sheep skins, a box factory, granite works, with 200 people employed; a dry dock for repairing vessels, a foundry, a planning mill, two sail-making establishments, and several builders of row and sail-boats, as well as many other industries that go to make up a thriving city containing in all about 10000 inhabitants.

These mills were on the island in back of Clark’s Store in Milltown Maine

The lumber industry is extensive along the St. Croix and its branches, and three firms have much capital and many men employed. The logs are cut along the lakes which compose the head waters of the St Croix. They are taken in charge by the St. Croix log driving company and are driven down and delivered to the mills, where each year about sixty million feet of boards and thousands of dollars’ worth of laths, shingles, orange and lemon boxes and other lumber products are turned out. The lemon boxes are sent to Sicily while the orange boxes are shipped to Florida.

The American Can cannery was one of several canneries in 1895 Eastport

The American Can cannery was one of several canneries in 1895 Eastport

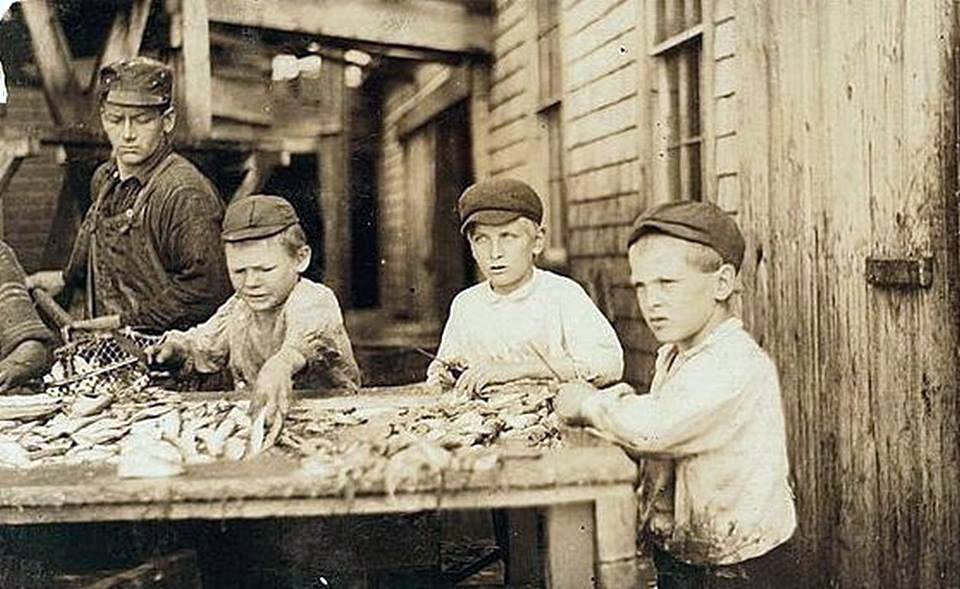

Probably no section of the United States is more interested in the fish industry than Eastport. on the coast. A gentleman employed in that place told me that no less than twenty-five factories. employing 4.000 hands, were engaged in canning sardines and preserving the fish taken in the surrounding waters. The sardines are caught in wire traps, which are arranged to imprison the fish by thousands. When the tide goes out, they are dipped from these traps, put into hogsheads and taken to the factories. With one stroke of the knife in the hands of good workmen the head is taken off and the entrails pulled out. They are then washed, put into salt pickle for from twenty minutes to one hour, according to the weather, then taken out and put on iron flakes upon which they are baked or broiled in an oven, after which they are put in oil and sealed in the cans as we get them. These factories each season pack about 450,000 cases, each case containing 100 boxes. There are also caught and cured quantities of haddock, pollock, cod, salmon, shad, herring, hake, smelt, lobsters, etc. All varieties of large fish are caught with hook and line, the hook being about three inches long, and herring are used for bait, halibut is scarcer than the other large varieties but pays better when caught, as it weighs from 75 to 100 pounds and sells for from 5 to 10 cents per pound, while cod and haddock are smaller and can be bought for one-half that amount.

Rolf Emery and Albert French, Salmon Falls Calais about 1900

It is said that truth is stranger than fiction, and I have found that the actual truth told of the hunting and fishing of this section is even stranger than the fiction one hears in Will Licklider’s store after the boys have been fishing on the quiet Potomac, or in Dr. Reynolds’s office after the huntsman has homeward plodded his weary way. I have not the space to tell one-half of the success in fishing and hunting in these parts but will try to condense in a few lines what would fill pages. In this portion of Maine one lake only ends where another begins, and a chain of lakes sixty miles long forms the west branch of the St. Croix, while another chain of lakes nearly as long forms the eastern branch of the same river. The lakes are said by all to be literally alive with beautiful, speckled trout, landlocked salmon and bass. The landlocked salmon, or salmon trout, are from 15 to 22 inches long and weigh from 2 to 8 pounds. Speckled trout and pickerel are smaller in size. Some of these fish are now being caught in the lakes, through holes cut in the ice. As to hunting, deer are plentiful and moose and caribou are also found. In Aroostook County moose and caribou are plentiful; woodcock, partridges and pheasants are numerous. Not very long since about eight miles from Calais a moose one morning came up with a farmer’s cows. The farmer shot the moose, which weighed about 800 pounds. A caribou will weigh from three to five hundred pounds. They go in droves of three or four, are similar in their habits to deer, but are easier killed. The fish and game laws of Maine are strict and rigidly enforced by a commission appointed by the Governor of the State.

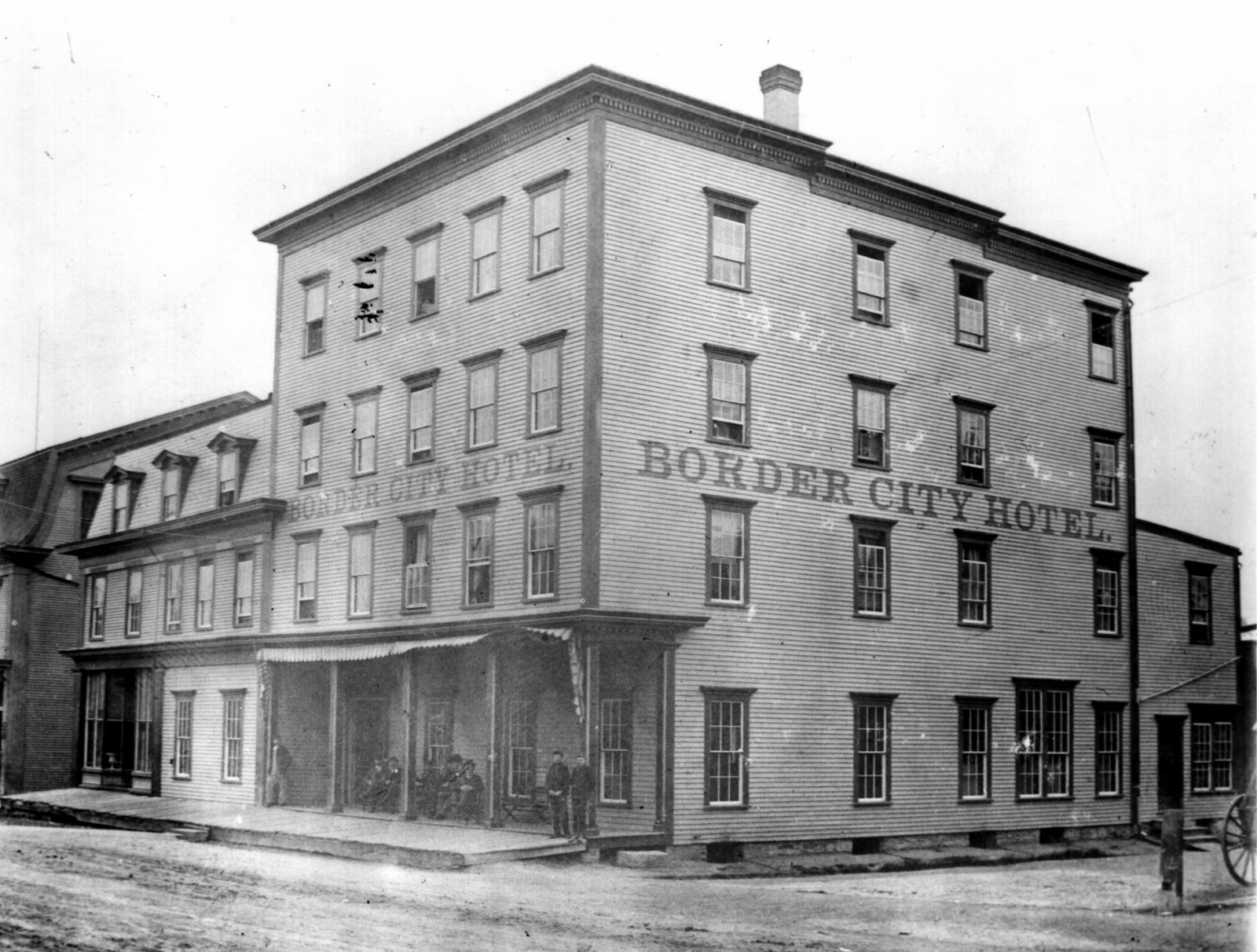

The Border City was demolished in 1939. The JD Thomas filling station was built on the lot in the 1940s.

I would like to be able to tell in fitting language of the kind manner in which I have been treated by the good people of Calais with whom I have become acquainted. Tis true the climate is cold, but the hearts of the people are warm, and you are shown the kindness you expect from your own folks at home. The people are thrifty, industrious and they live well, if I may judge from the abundance of well-cooked food, we get at the hotel kept by a jolly good fellow by the name of Daniel Gardner, and everybody seems to enjoy life thoroughly. There are many little occasions that are nothing in themselves, that seem strange to one who has been raised further South, just as our customs would be strange to those who come South. When I got to Boston I encountered baked beans, and as they are mighty nice, I don’t blame the New Englander for regarding with some little disgust the fellow who does not enjoy them. As I traveled further North on the vessel New England brown bread, made of corn meal and molasses, was added to the beans, and baked potatoes were also served. When I left the vessel at Eastport, I encountered for breakfast at the hotel a plate of doughnuts which, to the custom (which makes law) of the country, has since appeared as regularly for breakfast and supper as the sun gladdens the morning with his rays or wraps his bosom in the winding sheet of night. Some of the expressions of the folks here sound funny to me, and my way of talking of course seems just as funny to them. One can always tell from what section a man comes by his accent or way of talking. For example, when I am told that I had ought to see the fine potatoes that are raised up to Aroostook county, I know my friend has been raised in New England, and when I say, we raise a right smart of wheat in Jefferson County, like “Uncle Ben,” who met the colored Congressman in Washington, my friend knows that “dat fellow dun cum from de Souf.” These are only little differences, and on the whole people do not differ so much after all. I see many things to remind me of home and many faces seem familiar. although I have never looked upon them before. The children in the evening seem as glad to be liberated from school as are children are and the ladies on the streets are so tastefully dressed and good looking that they too remind me of the ladies of home.