When we left the story of Calvin Graves, Graves had fled from Fletcher Brook near Wesley where he had killed two games wardens, Lyman Hill and Charles Niles, who had threatened to kill his dog. The wardens claimed the dog, Smoker, was being used to hunt deer, a practice which had recently been made illegal in Maine. Although they had no proof of the allegation, the presence of Grave’s companion, James McFarland, a man well known to the wardens as a poacher, created a not unjustified suspicion that Graves and McFarland were engaged in hunting deer with the dog.

Other than Graves, McFarland and the two wardens the only other witness to the shootings was Ira McReavy, a teenager who was not acquainted with any of the others and was at Fletcher Brook with his father who was then in the forest cruising for timber. The boy later testified that the wardens told Graves and McFarland their policy was to shoot any dog they found in the company of hunters even though the law required proof the dog was to be used in the hunt to track or worry deer. After arguing at length with Graves and McFarland over the dog during which tempers flared, the hunters packed up to go home. Niles chambered a couple of rounds in his rifle and announced he was going to shoot Smoker. Graves reacted by killing both wardens.

McFarland went to his home near Hancock and soon surrendered to the authorities, Graves disappeared. McFarland was charged as an accessory to the killings and was tried in early 1887 and acquitted by a jury. It wasn’t until several months later that Graves was found nearly as far from Washington County as it was possible to go and still be in the United States.

Calvin Graves had successfully evaded the authorities and settled in Oakland California, then a city of about 35,000. Some reports say he even worked in law enforcement in a neighboring community for a spell. He was unable however to abide by the first two rules of the fugitive-don’t write home and never, ever provide even those you love most with your address-someone in the family will be careless.

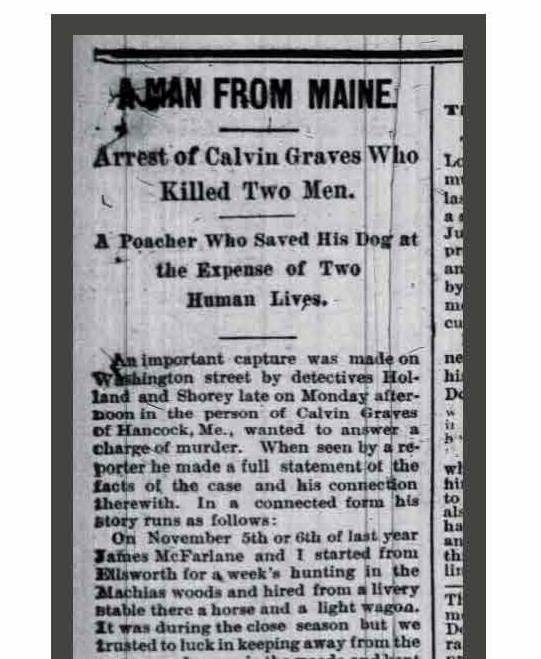

Oakland authorities were notified that Graves was living in the area and his description was provided. The police staked out the Post Office where Graves was receiving mail and other Oakland haunts and eventually located a man who somewhat fit the description. While the Oakland authorities thought they had the right man and questioned Graves, he denied he was from Maine or had any connection to the murders. In 1887 positive identification of fugitives was difficult if not impossible without a confession or identification by someone who knew the accused. However, the search of Graves hotel room turned up a damning piece of evidence- a clipping from the Boston Globe reporting McFarland’s acquittal on the charge of being an accessory to the warden’s murders. When confronted with clipping Graves confessed. The newspaper account below provides the first account we have of Grave’s version of the shootings.

Oakland Tribune March 30, 1887

A MAN FROM MAINE

Arrest of Calvin Graves Who Killed Two Men

A Poacher Who Saved His Dog at the Expense of Two Human Lives.

An important capture was made on Washington Street by detectives Holland and Shorey late on Monday afternoon in the person of Calvin Graves of Hancock, Me., wanted to answer a charge of murder. When seen by a reporter Graves made a full statement of the facts of the case and his connection therewith.

On November 5th or 6th of last year James McFarlane and I started from Ellsworth for a week’s hunting in the Machias woods and hired from a livery stable there a horse and a light wagon. It was during the close season but we trusted to luck in keeping away from the game wardens up in the woods and kept a good look out because McFarlane had been several times arrested for poaching. We took in the wagon everything necessary for camping out, and I took my bird dog along. On the 8th of the same month, a little before dark we were in Hemenway township, driving long by the Machias river and close to the Fletcher Brook House, when we were hailed by Charles Niles of Wesley and Lyman O. Hill of East Machias, deer wardens, and a boy named McReavy, hostler at the hotel. All along the road people we met warned us that our dog would be killed because the wardens had set out to kill every dog that came into the woods and had scattered poisoned meat in many places. My dog was a very valuable one, but I fell no danger because he was a bird dog and no good for deer.

The wardens came to our camp to see about the dog and Hill and McFarlane had some dispute about it. The dog was then in the house tied to a seat, and I untied him and made him fast to the side of the house. The wardens then left us for a little and McFarlane and I talked it over and decided to go home.

TO AVOID ANY TROUBLE.

When we were putting our outfit into the wagon the wardens returned. Everything was then packed except the dog and two guns, which were still inside. McFarlane took the dog to the wagon, and I brought out the two guns, breaking them down at the breech and drawing the cartridges. I tried to put them into my right trousers pocket, but as my mittens were there. I could not crowd them in, so held them in my left hand, which was the only thing that saved my life. Hill then ordered McFarlane to “give up the dog” and Mac refused but put him in the wagon. When I told them the dog was mine and they could not have him, Niles became abusive and pulled off his coat. He pointed his rifle directly at my head and pulled the trigger, but the cartridge didn’t fire. I then slipped a cartridge into my gun and fired, killing him instantly. Turning I saw Hill aiming at me with a revolver and put the second shell, which I held in my left hand, into the gun and fired again, killing him also. The boy McReavy saw the whole affair and told his uncle.

We rode on the road home until near Waltham seven miles from Ellsworth, where we turned the horse loose, and McFarlane and I parted company. I visited some of my friends and got money and took to the woods. After many adventures in the forest, I got away, beyond the reach of pursuing parties and came to Oakland on December l9th, but soon left for a trip through the State, from which I returned on the 5th of this month.

In explanation of the discrepancy existing between his statement that the killing was done in self-defense and his flight across the continent, Graves says public opinion was so high that he feared lynching, or at least he that he could not get a fair trial. This morning he expressed perfect readiness to return with the officers who will bring the requisition from the Governor of Maine.

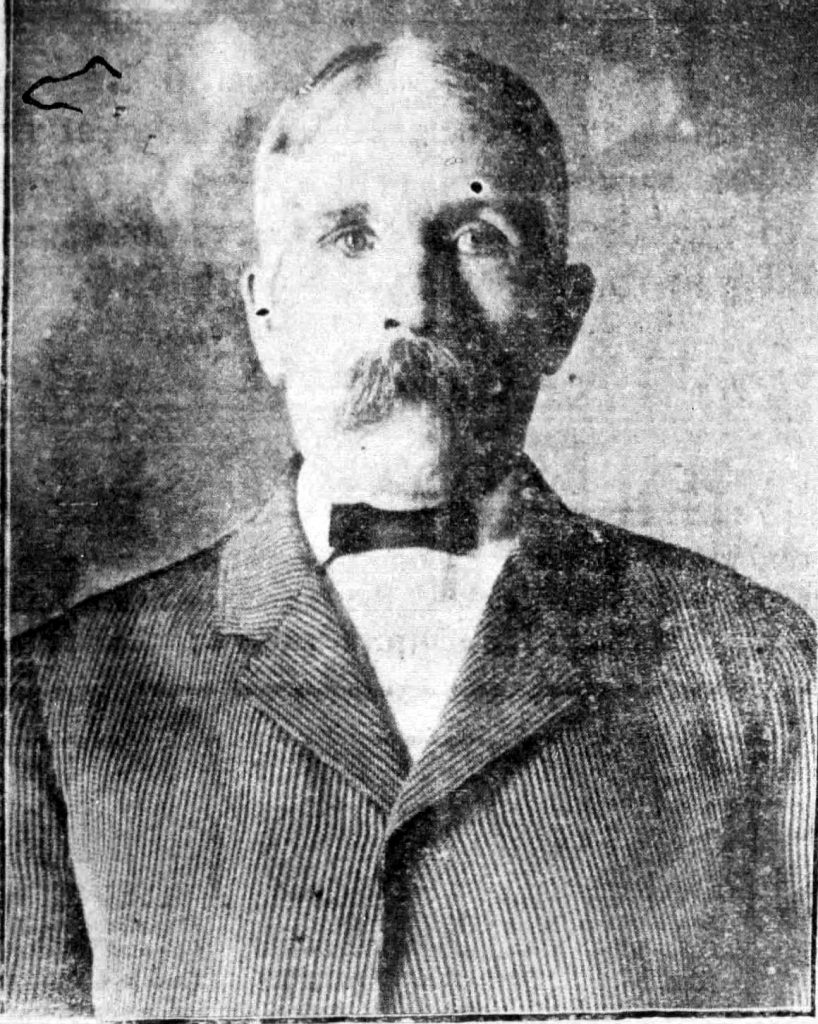

The Oakland police described Graves as:

…a decent looking man as seen in the tanks this morning. He has, like most men of the coast of Maine, been at one time a sailor, and later has been employed on farms. He has a wife and three children at home. He is by no means a desperado in appearance, but, on the contrary, has a quiet, intelligent manner. The reward of $1000 offered by Governor Bodwell of Maine has been cleverly earned by the two detectives, Holland and Shorey, who made the capture.

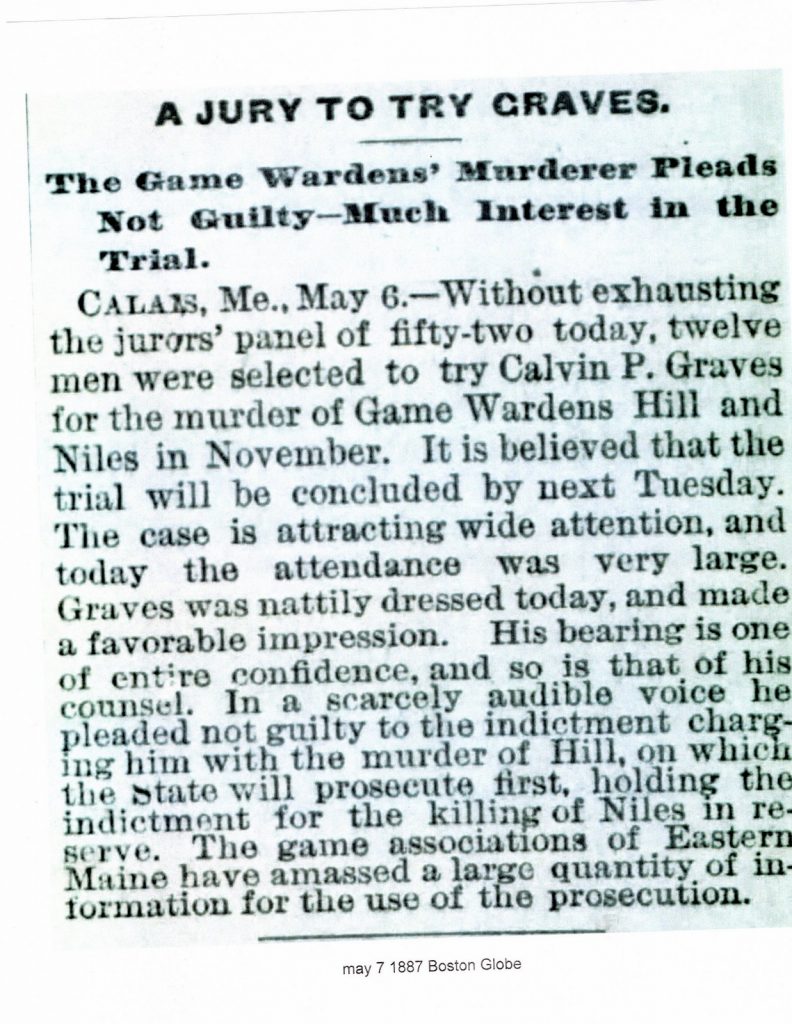

It happened that Calais was holding a term of court in May of 1887 and Graves was rushed back from California to stand trial. The Boston Globe reported his progress along the way and there was intense public interest when the ship transporting him docked in Boston.

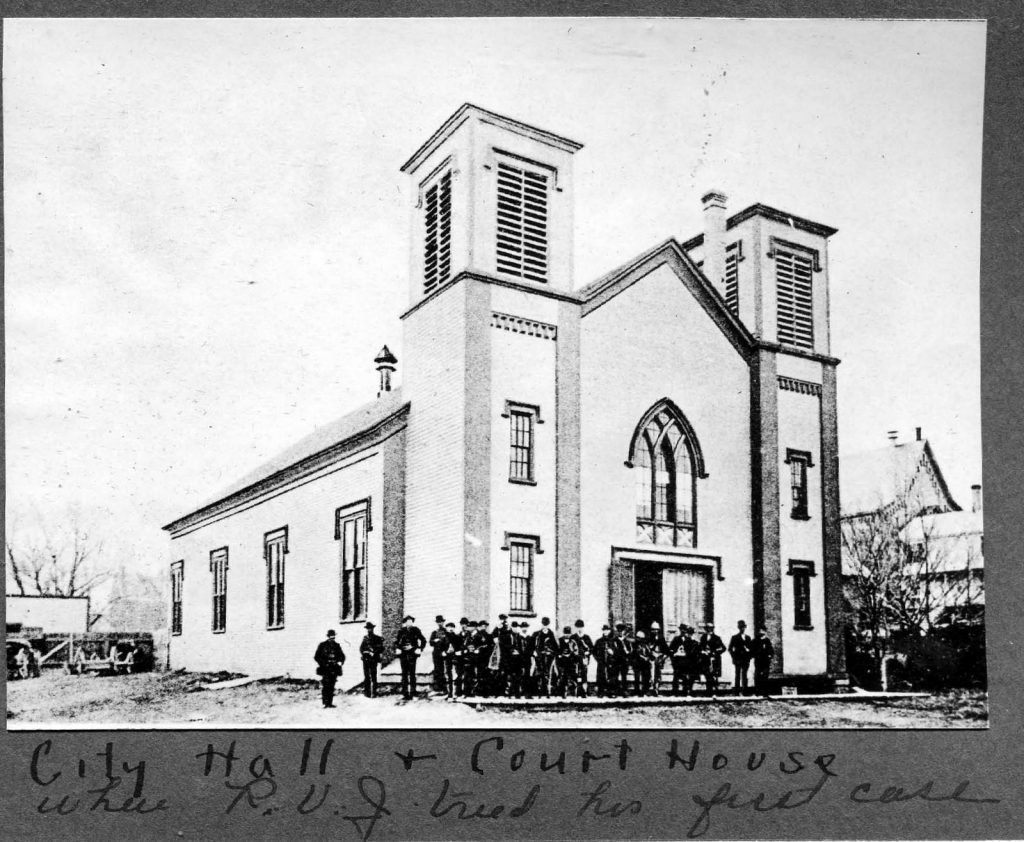

Graves was put on trial on May 9th and 10th, 1887 in the Calais Courthouse which was in those days was directly across the street from the present City Building. The trial was short and, as with many trials in those days, it is possible an unspoken agreement had been reached that Graves would not hang but the State would ask the jury for a conviction of second-degree murder which carried a life sentence.

If Graves thought he might possibly be acquitted like his friend McFarland he was disabused of this likelihood on the first day of trial. The McReavy boy’s testimony was consistent with his prior statements although inconsistent with some of his out of court statements and McFarland’s testimony, which certainly Graves hoped would raise some doubt as to his guilt, did little to help the defense.

Ira McReavy, then 18, testified that after a long argument with the wardens over the dog, McFarland and Graves loaded their wagon to return home, McFarland holding the dog in his lap in the seat of the wagon. Niles loaded his rifle and said, “We will take the dog” and it appears he may have leaned his rifle against the side of the building and approached the wagon to take the dog Smoker. Graves raised his gun and shot him as he attempted to take the dog and immediately wheeled and shot Hill. Graves then brought Niles’ gun to McReavy and said “Isn’t that gun cocked?” To which McReavy answered “Yes.” Graves said, “Damn you, no one cocks a gun at me.”

McFarland, Graves’ hunting companion, generally supported McReavy testimony. He also testified that Graves warned the warden’s “That’s my dog and don’t you shoot him.’’

The next day the defense presented Graves’ case primarily through the testimony of Graves and Mrs. Eben Bacon of Township 31. The theory of the defense was twofold-first that Graves had the right to shoot the wardens as he was acting in defense of his property, the dog Smoker and secondly that he acted in self- defense.

Lewiston Sun Journal May 10, 1887:

CALVIN GRAVES DOG

The Part It Played in the Fletcher Brook Tragedy

The Story Graves Told on the Witness Stand

The Theory of Self-Defense

Mrs. Eben Bacon who lives at Township No 31 testified that:

the day after the shooting Ira McReavy came to the house, he said Graves did the deed in self-defense. Niles wanted to pick a fuss. McFarland wanted to leave but Hill said no. The boy said he saw Niles put a cartridge in the gun and Niles said you wait, and you’d see some fun. As Niles was going out, he said: “I’ll kill the dog and the man who holds him.” Mrs. Bacon’s version of the boy McReavy’s story as related to her differed considerably from his testimony whilst on the stand. According to his statement to Mrs. Bacon, Graves did the shooting in self-defense.

GRAVES ACCOUNT:

Calvin Penney Graves, the respondent said: I am 42 years of age. I arrived at Fletcher brook with McFarland Saturday afternoon Nov 5. No one was there. Raymond Wilson and his father came later Sunday afternoon and Monday morning I went out hunting with McFarland about a mile. We took the dog as we were afraid it would be killed if left. I have no recollection of making threats against the wardens in Wilson’s hearing. The McReavy boy came about 11 o’clock and Niles and Hill about an hour after. Considerable talk took place about the deer law and other subjects in the course of which some hot passionate words passed.

Hill said: “You have a dog” McFarland replied, “Yes, a bird dog.” Hill then said, “You have no right to keep a dog like that,” to which McFarland retorted “I have a right to keep a dog in this State so long as he doesn’t chase deer.” Hill responded, “He has killed all the deer on our river and is going to keep it up here,” Niles said “No dog of any kind can come into my woods and go out alive.”

Witness tried to change the conversation thinking it was a small matter to quarrel over. McFarland asked if the wardens were going to stay all night and they said “Yes.” “I guess we’ll go home then.” I said “Why” asked the wardens to which I replied “If we don’t, we shall be discussing game laws all night.” McFarland and I than began to pack up and got everything out except witness’ gun and dog. Hitched the dog to a nail with the belt and went to fetch the dog. He was hitched with the belt which I then put on. I heard Hill say to Niles “I have seen his belt there to nothing in it.” I got my gun and removed the shells indoors. McFarland took the dog saying, “Bring my gun.” I took both weapons. Hill said “The shells are out of his gun. Kill the dog or kill the whole three of them”.

As witness passed out into the road he turned and saw a shot case which he had forgotten and returned for it. Walked to the wagon asked McFarland who had got in with the dog “Is your gun loaded?” “Look and see,” said McFarland. It was and I took out the shells and put the gun into the wagon. Hill said, “We must have that dog.” McFarland said to the boy “I take you as my main evidence forbidding that man to shoot.’ Witness said “Gentleman, you can’t have him. When you prove he has chased deer you can have him not before.” Niles than took off his coat and said to witness “Damn you and your dog too I’ll fix you.” He stooped to pick up his rifle and had nearly brought to a level when witness slipped two shells into his gun which was open and fired from waist high. Niles fell. He turned and saw something in Hill’s hand and thought it was a revolver and he then shot Hill down. When witness shot Niles, his gun was pointed towards him. I felt when he picked the gun he was going to try and shoot me, and I proposed to shoot him first if it was in my power. I also intended to shoot Hill knowing him to be armed. I called the boy’s attention to Niles’ rifle being cocked. He said: “It is cocked if ever I saw a gun cocked.” I left the spot as soon as possible. I did not make the threats assigned to me in regard to making way with the wardens if they molested my dog.

Attorney General Baker’s cross examination did not shake Grave’s testimony.

The verdict was quick and not unexpected-murder in the second degree. The mandatory sentence was life imprisonment and Graves was taken to Thomaston. Local papers on his route reported his passage through their towns as Graves had achieved a sort of celebrity status.

This was not the end of the story. By the early 1900s, a grassroots movement had formed Downeast to petition for Graves pardon. In 1902 a petition filed for a Graves pardon was supported by either 7000 or 10000 citizens of Washington and Hancock Counties depending on the newspaper account and ten of twelve the jurymen who had convicted Graves in 1887.

Even more surprising, the Judge who presided over the trial in 1887, Enoch Foster of Portland, wrote a letter to the Governor and Executive council supporting the petition. This was unprecedented in the annals of Maine jurisprudence. In the letter Judge Foster made clear that he had always felt an injustice had been done in the Graves case. While he regarded the conviction as proper he said there were many extenuating circumstances:

“I remember the impression that was made upon me at the time, that this man was carried away upon the sudden impulse of the moment and that his temper might be said to be ungovernable and there were circumstances which aggravated him to the commission of the crime. I feel strongly that no injustice would be done the State if executive clemency should be allowed in this case and a pardon granted.”

Nonetheless, the governor refused to grant the pardon. While there was overwhelming public support for the pardon, there were powerful political forces opposed including the Civil War veteran’s organization-The Grand Army of the Republic. Warden Hill was a disabled veteran of that war. Further not a few had more sympathy for the families of the deceased wardens than for the Graves family. As our own local historian Ned Lamb, a young man when Graves was released, remarked in an article about the case:

The years must have passed slowly for an out-of-doors man like Graves but probably just as slowly for the families of Hill and Niles with their bitter memories.

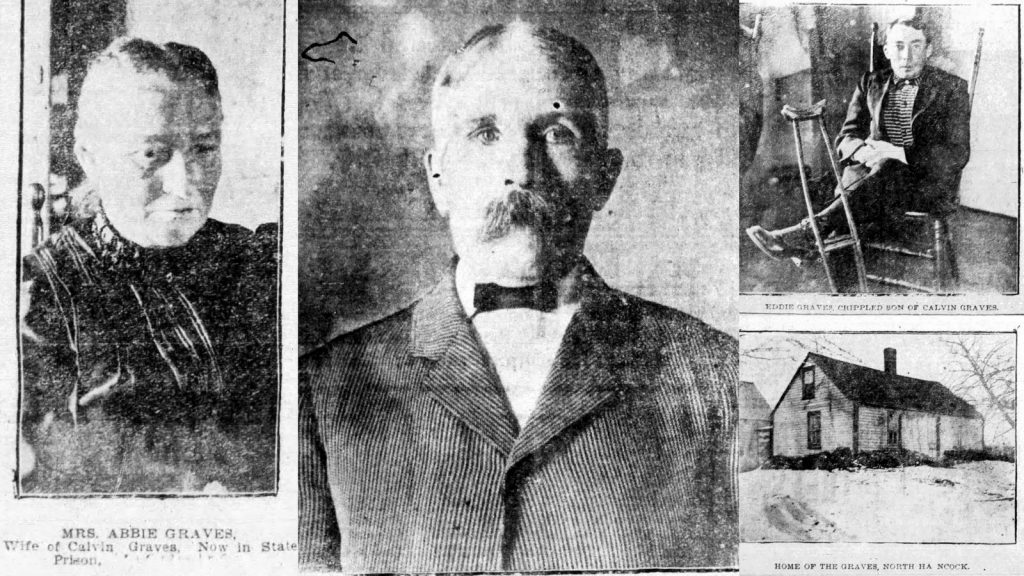

Still the newspapers continued to print articles about the Graves case and some recounted the travails of the family since Graves incarceration, never failing to mention his disabled and very popular son Eddie. The article in the Lewiston Sun from 1904 from which the above photos were taken is titled “Pathetic and Heroic is The Story of Eddie Graves.” Eddie was just a child when his father was sent to prison. According to the papers it is only through Eddie’s heroic efforts that the family had survived Calvin Graves incarceration.

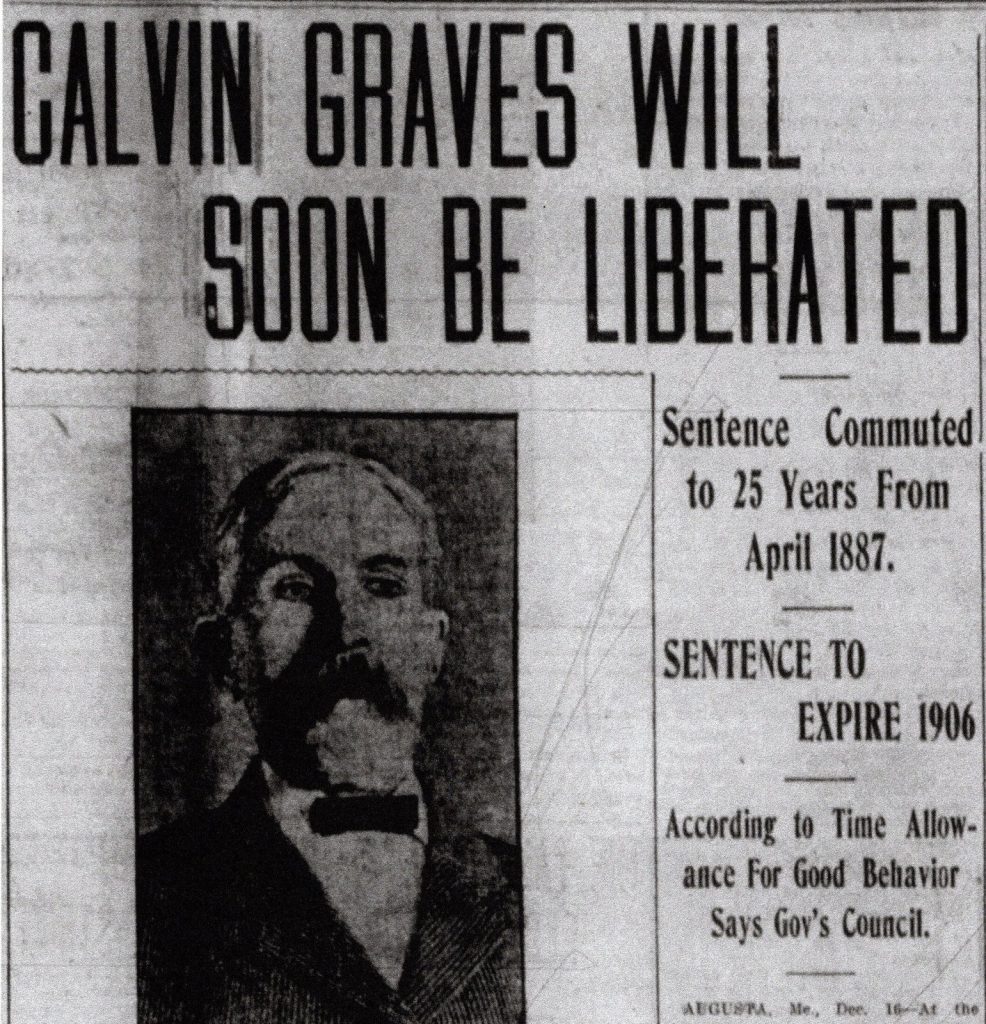

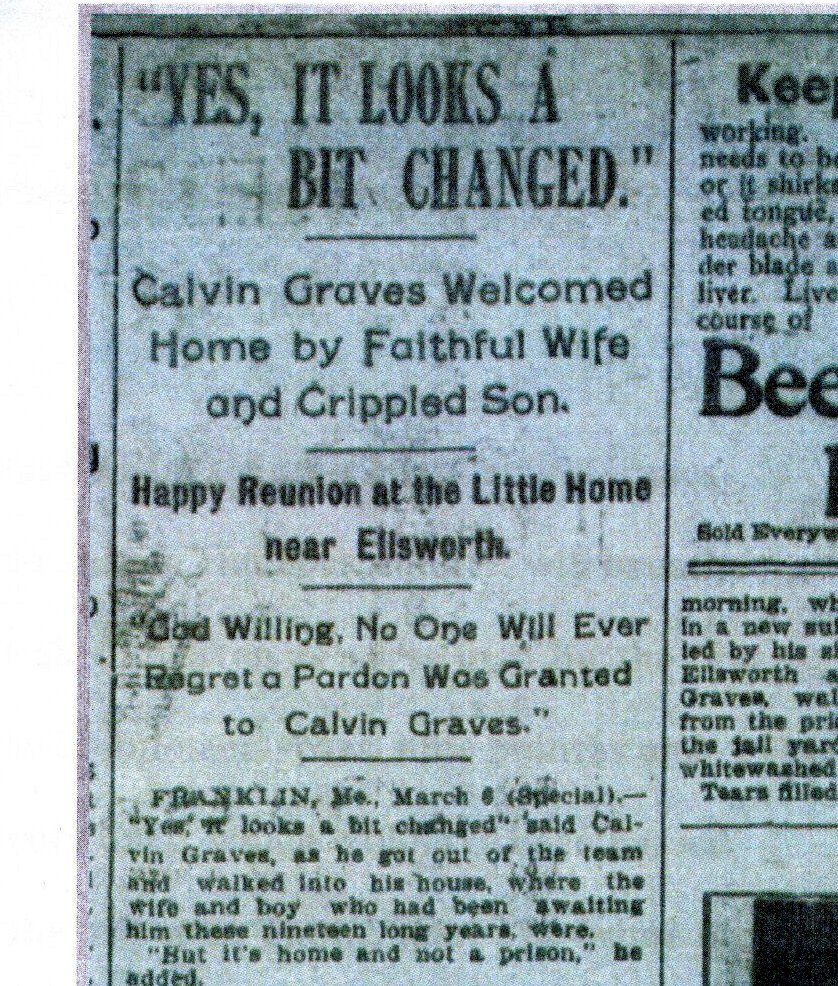

The pressure on the governor only continued and a compromise was finally reached in December 1904. Grave’s sentence was commuted to 25 years. With time served and good time credits Graves left Thomaston for his home in Hancock March 1906.

Many newspapers covered his homecoming. The article above included a photo of his wife Abbie, a description of his homecoming and of his life in prison. Other articles reported that Graves had received a patent for an invention while in prison for a device useful in sewing machines for which he had already been given $20000 and expected a good deal more. The articles stated, “The purchasers of the invention, which permits the use of a dozen kinds of thread at the same time, will do away with half the present parts of the machine.” No more is heard of this invention, but Graves did make the local news again as a witness in an illegal moose meat trial in 1912 and the national news in 1913 when he is said to have captured a mother and five young black foxes worth $15000 or more. This is the last mention we find of Calvin Graves in the newspapers. We have been unable to find an obituary for either Calvin or Abbie Graves.

It is fair to say Calvin Graves was guilty of murder and a long prison sentence was warranted. It is also fair to conclude, as the trial judge strongly implied in his letter supporting Grave’s pardon, that the wardens exercised poor judgment and their conduct only aggravated an exceedingly volatile situation. The wardens were undoubtedly doing their duty when they confronted Graves and McFarland. They had every reason to believe the pair were hunting deer out of season and that the dog was being used illegally for that purpose. Still, they had no evidence to support their suspicions. As Graves pointed out it was not illegal to have a dog in the woods, Graves and McFarland had killed no deer and there was much other wildlife the pair could have been hunting legally. When Graves and McFarland packed the wagon and said they were leaving, the wardens should have said simply “Well, be quick about it” and bided their time. They instead concluded wrongly that no man would kill two men to protect his dog and in this they were fatally wrong.