From at least the early 1870s until March 3, 1989, a large wooden building occupied the riverside corner of Whitney and Main Streets in Calais. The building was originally a part of J.A. Murchie’s shipping and lumber operation. Its many windows overlooked the Ferry Point Bridge, the upper wharves and had a commanding view of the river and St. Stephen. It is no exaggeration to say the history of Calais literally passed before its eyes. For the last hundred years of its existence the building was in the possession of the family of Israel Andrews whose descendants have long lived in the area. Dorothy Burns and Lillian Marino, granddaughters, although both now deceased, are fondly remembered.

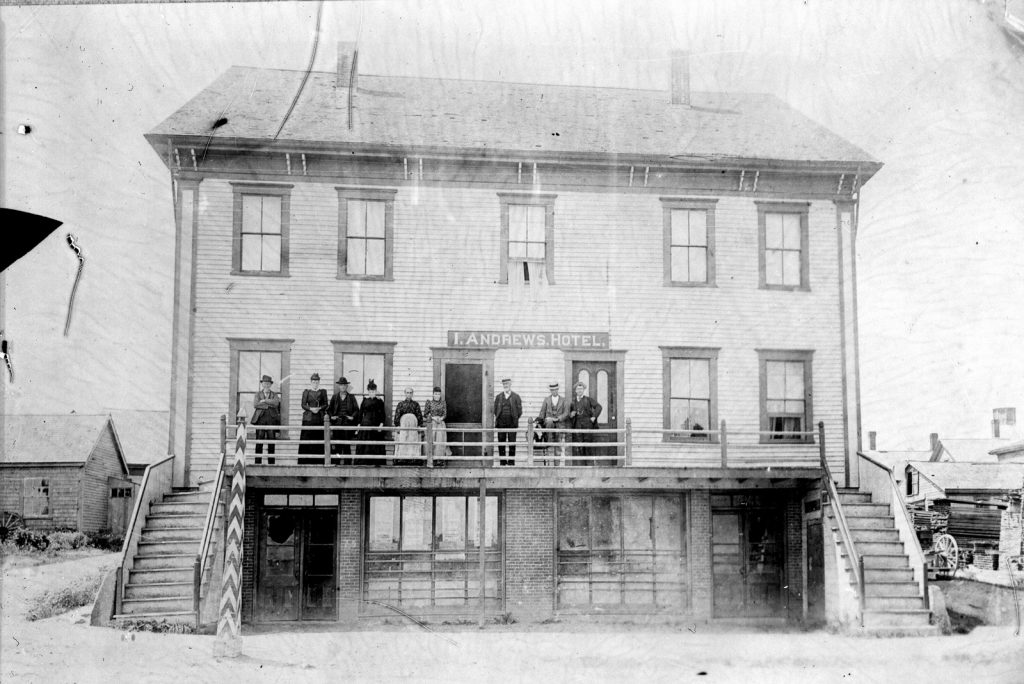

Israel Andrews was a native of Grand Lake Stream. We interviewed Dot Burns several years ago and she said Israel moved to Calais in the late 1880s and bought the building soon after his arrival. In Richard Rees book “Images of the Past”, a caption under a photo of the building says Israel moved to Calais in 1892 at the age of 68 and opened the Riverview Hotel, later renamed the Andrews Hotel. A blacksmith, renowned hunter, and sharpshooter, he is described as a strong temperance man who refused to have liquor in his hotel. Israel is such an interesting fellow we will do a sketch of him in a subsequent article. It is said he could thread a needle without glasses and continued to do all the buying for the hotel, on foot, until his late 80s. After Israel died in 1916 his son Thomas became the owner and the business was thereafter known to most as “Tommy Andrews” even after Tommy’s death in 1960.

Tommy did much to improve the business. He was one of the first in town to install a radio – the new wonder of the age – in the hotel lobby. He was well liked in town and the store became a center of civic events during 4th of July celebrations when races either began or ended in front of the hotel. Much like his father he knew how to handle an emergency. On November 6, 1918, the Bangor Daily News reported the following Calais news:

David Foster, the five-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. Harry Foster, fell off the wharf Saturday afternoon and was sinking for the third time, when rescued by Thomas Andrews, proprietor of the I. Andrews Hotel of this city. His brother, several years older, who was unable to swim, ran up from the wharf and met Mr. Andrews near the hotel. Mr. Andrews, who had just recovered from a three-week illness, gave no thought to his own personal danger and hastily running to the wharf jumped into the water and saved the youngster in just the nick of time. Fortunately, both were none the worse from their plunge into the cold water. This makes the second heroic rescue of drowning persons in that neighborhood this year. The other one was the rescue under similar circumstances of Vera Cove by Ned Murchie who also bravely jumped in and swam with her to safety.

The above photograph of the hotel shows a large, three storied building with staircases to the porch which ran the length of the second floor. The people in the photo are probably guests. According to Dot Burns, the ground floor contained the hotel lobby, a small store and a dining room for the hotel guests and the general public. Dorothy confirms that no liquor was sold in the restaurant or from under the counter of the store. This was somewhat unusual in this part of town as Main Street from Union to the bridge was notorious for bars and speakeasies and was the first place a thirsty sailor would go to drink after a long, dry passage. Maine had prohibition long before the Volstead Act but the bootleggers in the Union always assured a steady supply of alcohol to the locals. The second floor of the building was the family quarters, the third contained 10 rooms for guests and the attic had four large rooms which were also rented when demand was high. In back was a large barn which Dot says was called the “eel house”. For many years the St. Croix River eels were as much a delicacy as lobster to the Germans and Dutch in New York. These were packed in wooden barrels with a large block of ice and shipped by sea to the big cities where they arrived alive and well. John Brooks of Robbinston says he made enough profit in one three-month period of the late 1930s shipping eels to pay for a new Ford pickup.

Neither Dorothy nor Lillian remembers much about their grandparents. Their father, Thomas, was born in Grand Lake Stream and as noted above helped his father Israel operate the hotel in the early years. In fact, it was Thomas Andrews, Israel’s son who eventually purchased the hotel from Murchie in 1912. Until then Israel had leased the building. Thomas married Elizabeth MacDonald who was born in Landsdown, N.B. Elizabeth had been previously married to a Mr. Jennings and moved to Chicago. She returned to Calais with her two children, Thomas and Geraldine Jennings and married Thomas Andrews. Thomas and Elizabeth had two children of their own, Dorothy and Lillian, both born during the First World War. Also born to a Burns family of St Stephen early in the war was a son Barry, who will play a prominent role later in this history.

Dorothy and Lillian were both born in the family quarters of the hotel and lived either in the hotel or the house on the other corner of Whitney Street until the late 40s. Dorothy has vivid memories of the hotel, the bustle of the docks, sailors and transients taking rooms and the “big beautiful ships” coming up the river to turn and dock at the upper wharf or the other working docks on both sides of the river. In those days the steamships, the Charles Houghton, Rose Standish and Henry Eaton disembarked large numbers of people at the upper wharf just below Ferry Point on a daily basis. Many would have strolled up Main Street and some would have stopped at the Andrews Hotel dining room for a meal. They would have observed two little girls, Dorothy and Lillian, eating at their own private table.

By the 1930s the general economic decline of Calais and especially the waterfront resulted in the closure of the hotel. Only Albert Murchie, a long-time resident, was allowed to keep his rooms. The family continued to live on the second floor, but the ground floor was transformed into what many of us remember as “Andrews Tobacco Stand.” The porch was removed as were the stairs on either end of the building. The front of the building can be seen during this era in the 1942 photo above. Rooms were still available during the war.

In the mid 1930s Dorothy Andrews married Barry Burns of St. Stephen. They moved into the house on the other corner of Whitney Street in the late 1930s and in 1937 had their first child, also named Barry. By the 1940s the elder Barry was much involved in the operation of the store and after his return from military service in the Second World War, he took over the daily operation from Tommy although Tommy and Elizabeth continued to occupy the family apartments on the second floor. Tommy Andrews died in 1960, survived by Elizabeth and their two daughters.

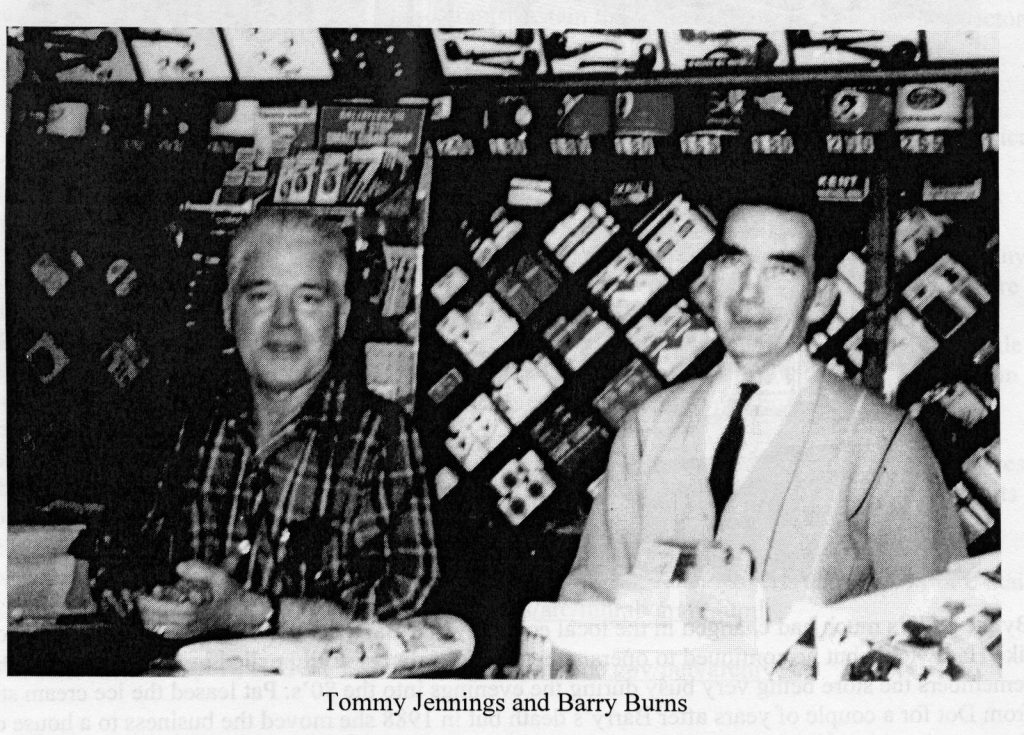

Being born in 1947, my first memory of the store is from the early 1950s. My grandmother, Lillian Towns, lived just up the street from the store on Whitney Street and when I was young, I spent a lot of time with her. She didn’t have a car or, if memory serves me, know how to drive so we walked everywhere and every trip, whether up Main Street in Calais or across the bridge to St. Stephen took us by Tommy Andrews store. Tommy Jennings and Barry were, it seemed, always in the store. As I had always heard the store referred to as “Tommy Andrews,” I naturally thought Tommy Jennings was the owner and couldn’t understand why Barry seemed to be in charge but there was no question Barry was the boss. Barry Burns was a very astute businessman whose motto, according to his niece Pat Tocchio, was to never, ever pay someone else to do something you could do yourself.

The photo above of Barry and Tommy Jennings shows them in a familiar pose behind the main counter. This counter was to the left as you entered the store and behind them is the vast array of tobacco products sold in the store. In the 60s and 70s it is said Andrews Tobacco sold more tobacco products than any other store in the state due largely to the Canadian trade. The store also sold penny candy, ice cream, souvenirs, soda, books, magazines, comic books and, by the 50s, beer. For a mere 5 cents young scholars could choose from a large selection of Classic Comic Books and avoid the drudgery of reading Ivanhoe, Silas Marner or a hundred other classics assigned for book reports. Ice cream on a stick, handmade by Barry, was in a cooler to the right of the main counter as were many flavors of soda, bottled by Barry.

By the 1960s Barry, Tommy Jennings, Dot Goode and Barry’s sister Molly were working in the store and Barry had introduced the ice cream stand to the right of the store entrance. Jane Marino, Lillian’s daughter, recalls helping Barry make the ice cream which he served at the dairy bar. Large metal milk containers were lifted with pulleys from a refrigerated tub and the flavors, also prepared by Barry, were stirred in by hand with a large paddle. These were put in four-gallon containers and sold in the dairy bar. Andrews always had vanilla and at least one other flavor, banana, orange pineapple, chocolate, strawberry or coffee. Barry taught his niece Pat Tocchio the art of making ice cream in the 1970s, an art she practiced at her takeout on Whitney Street. Barry also bottled his own soda with a bottling machine which cleaned the bottles, added the syrup and carbonated water and capped the bottle all in one operation. Pat Tocchio recalled Barry setting aside a few days a year for bottling soda, a time when everyone in the family had to help out.

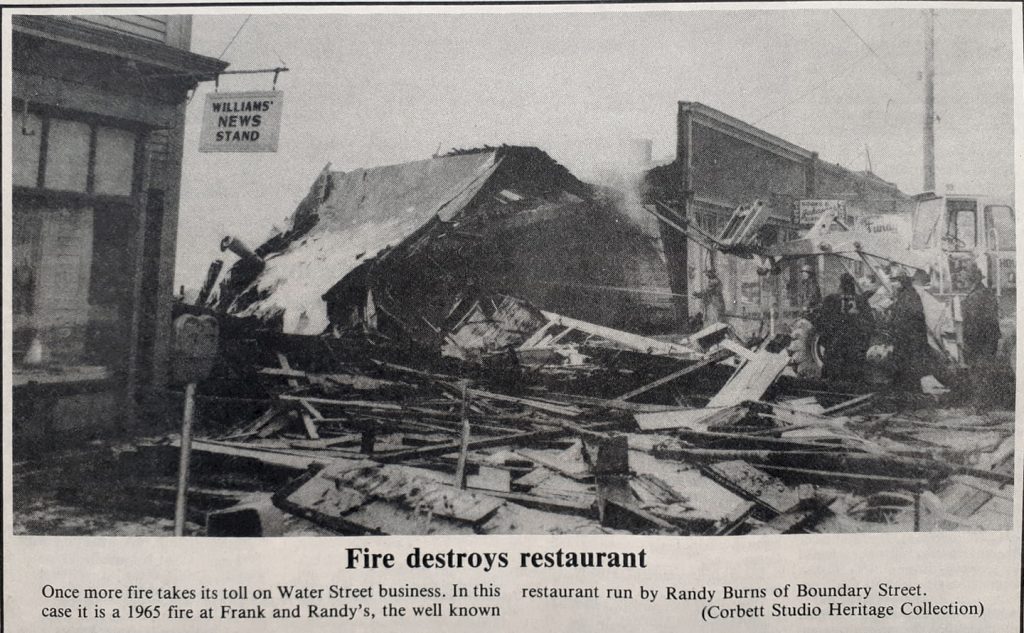

In the 1960s Barry added hot dogs to his inventory when Randy Burns, his brother, lost his business in St. Stephen to fire. Frank and Randy’s was one of the most popular spots on the border, selling fish and chips for 35c and a hot dog for a dime. After the fire, Randy came to work for Barry and brought his unique method of cooking hot dogs with him.

By the 1970s much had changed in the local economy and Barry had more competition from places like Hardwick’s, but he continued to operate the business almost until he died in 1985. However, Pat remembers the store being very busy during the evenings into the 80s. Pat leased the ice cream stand from Dot for a couple of years after Barry’s death but in 1988 she moved the business to a house on the opposite side of Whitney Street where the same ice cream and specially cooked hot dogs were on the menu. On March 23, 1989, the building was demolished, and another part of Calais history was gone forever.

The Andrews family, their guests, customers and friends had as fine a view of Calais history for 100 years as anyone in the city. Who wouldn’t give a great deal to have spent just one day in the 1900’s sitting on the porch of Israel Andrews Hotel watching the ships docking at the piers, the streetcar taking on and leaving passengers on the sidewalk just below the porch, the people and wagons on the bridge and the beehive of activity which was the Calais waterfront well into the 20th century.