By Thomas Fleming, New York, New York

From “Guide Posts, Great Moments in American Faith” June 1994

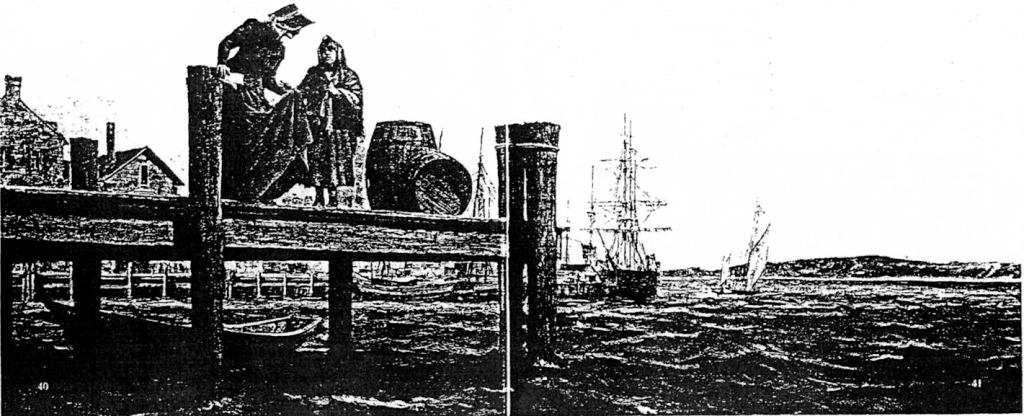

Respectable women were seldom seen on the waterfront in Calais, Maine, just across the St. Croix River from Canada, in the 1880s. The streets were full of brawling sailors, and lined with rough saloons known as “’blind tigers”. That was why everyone stared unbelievingly at the sight of lovely Mary Woods, wife of one of the town’s most prosperous merchants, wandering down those mean streets toward the river one gray day.

They did not know they were witnessing a spiritual collapse. In her hands Mary Woods clutched a telegram: EMMA DEAD IN CHILD-BIRTH. BABY GIRL ALIVE. Stumbling out on a pier,she stared into the black rushing river. She had placed the last of her dwindling faith in her daughter Emma’s happiness, and God had flung it back in her face.

With bitterness, Mary pondered the fates of her other children. Her firstborn, a blue-eyed little daughter and then the twins, gone in one awful week with measles. Then sturdy, fun-loving, Charles struck down at 10 by an iced snowball. Then Ella, who died of cancer at 12 and Will, who succumbed to typhoid fever in college.

Emma had been Mary Woods’s consolation. Graduated from Vassar in 1878, she came home engaged to marry her roommate’s brother. Emma had been so happy that Mary and her husband, William, could not object, though their hearts ached at the thought of how seldom they would see her. Now she too was gone.

The river churned hungrily against the pier. Come to me, it seemed to whisper. Let me be your answer. –

“You goin’ to jump?” It was a child’s voice. Mary Woods turned and stared into the dirtiest face she had ever seen. The ragged filthy dress told her it was a girl. It would have been impossible to tell from the lank unwashed blonde hair and the grimy monkeyish features.

“If yez are gain’ to jump, I’ll jump with you,” the little urchin declared. “I’m scared to do it alone.”

The shocking words abruptly cooled Mary Woods’s self-pitying rage. She thought of her husband: He would be devastated by her loss. “I’m not going to jump,” she said. “I must go home.”

“Take me with you,” the little girl begged. “I’m hungry. Mother didn’t come home last night.”

Mary Woods seized the girl’s grubby hand. “Come,” she said.

Mary took the girl back to her spacious house, gave her a bath and dressed her in some of Emma’s old clothes. She watched her devour as adult-sized meal and listened to her chatter while she ate. Her name was Millie. Her “mother” was a woman with whom her real mother had left her years before.

“There’s lots of kids like me,” Millie said. “At least I got a place to sleep at night. Some kids sleep in alleys. In the winter they sneak into saloons and sleep in the cellars. But sometimes they get caught and thrown out. One boy froze to death last year.

Mary Woods’s rage at God vanished. Instead, her mind blazed with inspiration. “Millie,” she said, “would you like to stay here with me?”

“Could I? I’d do anything, ma’am. I’d work.”

“I don’t want to hire you. I want you to stay here while I find a young couple who would be a real mother and father to you.”

“Are there people like that?” Millie asked.

“Of course there are,” Mary said, without being at all sure she was right. Tomorrow we’re going to the riverfront to find other children who need homes. You know who they are.”

With those words, Mary Woods began a new life with a renewed faith. The next day she brought home three more children. They too were cleaned, fed and clothed. Then Mary called a meeting of the Calais Benevolent Society- a group of women who helped the poor- and told them about her plan. A dozen members offered food, money, time.

They did not realize they were pioneering a movement that would eventually place millions of children in adoptive homes. In those years, there were no social workers or juvenile courts. Mary Woods and her friends had to feel their way, relying on their own judgment and prayers. But they quickly worked out a system that would do credit to the best social services agency today. Mary retained a lawyer to guarantee the legality of each adoption. An investigation committee certified that a child’s parents were dead or missing. Within a month they had successfully placed Millie and her three friends in caring homes.

Mary Woods became a familiar figure on the waterfront. Children flowed in and out of her house. She was elected president of the Calais Benevolent Society and persuaded people of means to donate generously.

Then another little girl with another kind of loneliness arrived at Mary Woods’s house- her granddaughter Emma. She was the baby mentioned in the telegram that had almost driven Mary to suicide. Emma was a moody, unhappy creature. Her father, who had remarried, found it difficult to communicate with her. In frustration, he sent her to Maine to see if her grandmother could do anything with her.

All her life Emma had been surrounded by a thick cloud of pity, which had inevitably become self-pity. Mary Woods decided to try a swift, radical cure. She took Emma along to the waterfront.

They returned with a little girl named Pearl, who was at least as dirty as Millie had been. Quickly Pearl was hustled to the woodshed, where Mary and her doughty Irish maid, Hannah, whisked off her clothes, doused her hair with kerosene and combed out the lice. Then came a hot bath and some hard scrubbing, while Pearl punctuated the summer afternoon with a series of wails and shrieks.

Neatly dressed but still wary of her new life, Pearl played with Emma, who offered her one of her dolls. “I’ve never had one,” Pearl muttered.

“I’ve got lots of dolls,” Emma said and quickly fetched another one from her bedroom. “Let’s pretend your baby is crying and make it stop.”

To Emma and Mary’s horror, Pearl slammed the doll against the wall. “No, Pearl,” Mary Woods said. “That isn’t the way you stop a baby from crying. You stop it by loving it.”

“How do you do that?” Pearl asked.

Mary Woods picked up the other doll and began singing it a lullaby. Both children were awed by the love that shone forth from this woman. Emma began to realize there was more to life than feeling sorry for herself. For the next 10 years, she returned to Calais each summer.

One of Mary Woods’s hardest cases was a boy everyone called “Harmonica John”. He was a cocky fellow who picked up pennies playing the harmonica in the blind tigers. Mary Woods placed him in the home of a music teacher. The teacher reported that John had real musical talent, and he looked forward to educating the boy.

But within two weeks John had run away. Mary Woods and Emma headed for the waterfront. They found John in one of the worst blind tigers. Mary seized him by the collar and marched him home. “You need to learn a few things about life, young man”, she said.

She shipped him to a strict private orphanage in Boston. But she combined this punishment with some shrewd motivation. She arranged for him to be taken each week to a concert given by one of the many great musicians performing in the city.

Soon he was begging to go home and begin the musical education his adoptive parents had planned for him.

Mary Woods remained an active president of the Calais Benevolent Society until she was in her 80s. The society is still going strong. Members are no longer involved in adoptions, but each year they dispense thousands of dollars in emergency aid for food, clothing, medical bills.

When Mary Woods died at 89, Emma made the funeral arrangements. “Are there any living children?” the minister asked.

Emma was about to say no when the telephone rang. It was Harmonica John, who had made a career playing woodwinds in leading symphonies throughout the East. He had come from New York and had brought with him five more of Mary Woods’s “boys”. On the day of the funeral they carried her coffin into the church. Two of the pallbearers were sailors, two were farmers, one was a minister and the sixth was the distinguished musician.

No living children? Emma thought. In a moment of awful spiritual darkness, Mary Woods had won the power to communicate love and faith to dozens of children. Among those, Emma included herself. She had become a strong caring woman, thanks to Mary’s radiant spirit.