The St. Croix Valley has rarely merited much mention in the national press over the last couple of hundred years with a few notable exceptions. The War of 1812, which saw the Brits occupy Eastport, was one of these and there was no end of “smuggling” stories in the papers over the years which basically portrayed Downeasters, quite truthfully, as renegades and tax evaders. Next week [January 25], however, marks the 41st anniversary of the Bangor Federal Court’s decision in the Baileyville Book Banning case, which put Downeast Maine and Baileyville in particular on the map like no other local story before or after. Many have probably forgotten the details, so we’ll provide some background.

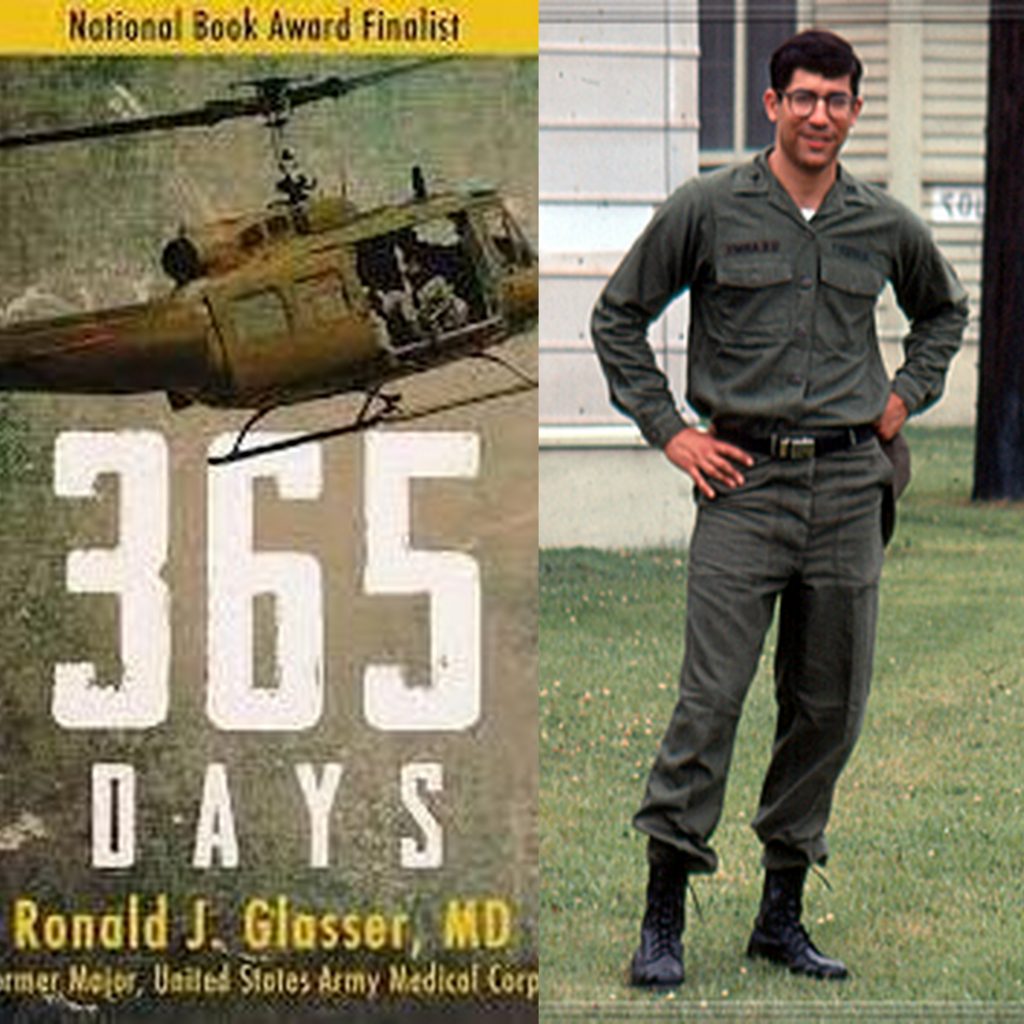

In 1971 former Army doctor Ronald J. Glasser wrote a nonfiction book which contained accounts of a number of American combat soldiers who had been wounded in Vietnam and transferred to Japan for medical treatment. While treating these soldiers, whose wounds would have been serious to have warranted transfer to Japan, Dr. Glasser spent time interviewing them about their experiences in Vietnam, taking notes and quoting the soldiers at length in the book. The soldier’s descriptions of combat were graphic in detail and the language used was by the soldiers to describe often terrifying experiences was not, according to a Calais combat veteran who testified at the Bangor hearing, the sort of language he would have used at his kitchen table at home, but it was the language of the Vietnam infantryman.

When the book was published in 1971 it was widely acclaimed and nominated for the National Book Award and the Woodland School added it to its collection in that year. According to findings made subsequently by the Federal Court in Bangor, over the course of the next decade the book was checked out of the library 31 times. In the spring of 1981 it was taken out by the 15 year old daughter of Mrs. Carol Davenport. Mrs. Davenport was informed by a friend that the book contained “objectionable language” and after obtaining the book from her daughter, she agreed, being especially offended by a sexual expletive used in a chapter title. The word, always referred to during the Court proceedings as “The Word” was helpfully described by the Superintendent of Schools Ray Freve as a four letter word meaning sexual intercourse.

Mrs. Davenport discussed the matter with the Reverend Roy Blevins of the Woodland Baptist (where she was a member), who advised her to take up the matter with the school board, which included two other members of the church, Stephen Neale and Clifford McPhee. The Chairman of the School Committee was contacted and at the next meeting of the school committee, the book, although the school librarian had not been consulted and the matter was not on the agenda, was brought up, and a motion made to ban it. The vote was 5-0 in favor of banning the book even though none of the school committee members had read the book. Two members of the committee, Susan White and Xavier Romero, had second thoughts after the vote and after reading the book tried to have the decision reversed but to no avail. The book was removed over the objection of the school librarian. Subsequent attempts to retain the book in the library on a “restricted” shelf under the control of the school librarian were defeated 3-2.

After the book had been banned, a senior at the school (Michael Sheck) asked the school librarian for the book and was told it had been banned. After Shenk had exhausted all efforts to resolve the matter he contacted the Maine Civil Liberties Union and the battle lines were drawn. The MCLU retained Ronald Coles who had practiced law in Machias for many years, suit was filed in the Federal District Court in Bangor and a motion was made by Coles for an injunction to force the school to put the book back on the library shelves pending a final trial on the question of whether the removal of the book violated the constitution rights of students at Baileyville.

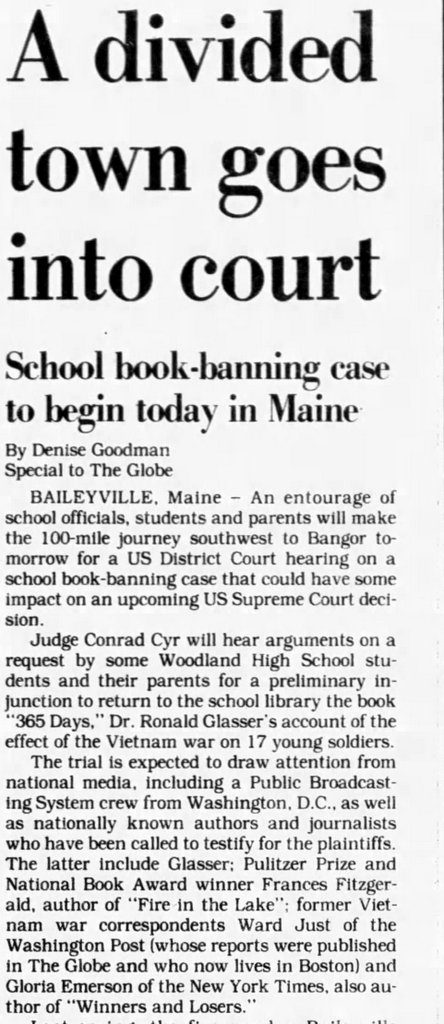

The national press soon began reporting on the case which was set for a hearing on the preliminary injunction on December 21st 1981. The Boston Globe published an article on November 29th reporting on the dispute and the split on the school committee.

Committee member Clifford McPhee was quoted as saying: “To put that word in large dark print alone on the page, would be pornographic to some children,” while Romero, who regretted his initial vote, said: “Even if I object to the to the language I believe the book has a good message. Maybe he could have used different language, but the impact would not have been the same.” The other dissenting school committee member Susan White said, “I don’t think it’s my choice to tell students what they should and should not read.”

Even the school committee’s attorney, Francis Brown of Calais (and himself a veteran) had qualms about the ban and was quoted in the Boston Globe article the day before the hearing agreeing 365 Days is “an excellent book” and “I wouldn’t be troubled by high school students reading it. All I can do is present the facts to the judge…. we want the judge to know we have a divided community and a divided board. It’s a practical difficulty for a school committee to know what to do when parents complain.” Still the majority of the school committee chose to proceed to court.

The hearing began on December 21st, 1981 at the Federal Court on Harlow Street in Bangor. Veterans in full combat gear picketed in front of the courthouse in support of Major Glasser and the book. The national media was present in droves including film crews which Judge Conrad Cyr refused to allow in the courtroom. Ronald Coles represented Michael Sheck with Dan Lacasse and Francis Brown of Calais representing the school committee.

The Bangor Daily summarized the first day’s proceedings:

Bv Wayne Reilly NEWS Education writer

Witnesses including four prominent authors Monday debated what four-letter Anglo Saxon words should be allowed in a high school library while Vietnam War veterans dressed in jungle fatigues picketed outside as the Baileyville book banning trial began in US District Court in Bangor.

“We don’t want to see any more 18-year-olds go to war without knowing what it’s about” said Sterling Doughty chairman of Vietnam Combat Veterans of Maine His group was calling for the return of the banned book 365 Days a non-fiction account of the war to the shelves of the Woodland High School library.

The book was banned from the Woodland High School library after Carol Ann Davenport, the mother of a high school student objected to the book and convinced the school committee to remove it.

A lawsuit to restore the book to the library shelves was brought by then Woodland High School senior Michael Sheck along with other students and some parents. Machias lawyer Ronald Coles, sometimes using dramatic hard-hitting techniques before the packed courtroom, summoned 10 witnesses most of whom agreed the book should be returned to the library. At issue is when a school board can abridge First Amendment rights.

One of those testifying was 365 Days author Dr Ronald Glasser, whose book of vignettes about the lives of maimed and dying soldiers in Vietnam has been translated into nine languages and made into a play.

“I had to use those words because those words were portrayed to me by the patients I talked to….it’s inappropriate and demeaning not to deal with the truth,” said the Minneapolis pediatrician who has written three other books at night after work.

The use of four letter words by soldiers represents “a common language failure” said Glasser. “They couldn’t say golly gee and they didn’t. It wasn’t enough. (The words) showed their anguish. They don’t go home and use that language. They were desperate.”

Glasser said he couldn’t understand the action of the Baileyville school board “because they are ignoring the problems that their own children face.”

Ward Just, former Vietnam correspondent for the Washington Post and author of eight books, said: “It is not possible to take the slice (of the war) that Ron Glasser did and do it in Victorian language.” Just said the book is an “extremely important and sensitive part of the war, particularly for young men. A teenager reads that book and immediately he recognizes that it’s another teenager talking to him.”

Gloria Emerson, former New York Times Vietnam correspondent and National Book Award winner said she found the book’s language “rather modest” compared to the way soldiers talk and that she would not hesitate to recommend it to a young teenager.

“I had not wept in Vietnam although I saw things I could not imagine before I went. I was glad to see I wept when I read Ron’s book because I could see I was still alive,’’ she said.

Pulitzer Prize winner Frances Fitzgerald, war correspondent and noted textbook critic, said most school history textbooks avoid the Vietnam War because it is still controversial, making Glasser’s book all the more important for a school library. The soldiers she encountered swore “sometimes almost exclusively.”

Woodland High School librarian Grace Schillich and English Department Chairman Jean Spearin voiced their opposition to the banning of 365 Days but school board chairman Thomas Golden and Principal John Morrison remained adamant in their support of the school board’s majority along with Carol Ann Davenport parent who asked that the book be banned.

But they said they did not believe the book was obscene under a legal definition read by Coles and they said they were not trying to impose their political values just trying to keep dirty words away from teenagers.

Through his questioning Coles made the point that two of the three board members who refused to submit the book to a new controversial materials policy last summer had not read the book and that there had been little consultation with educators.

He repeatedly asked witnesses if they had ever seen a student who had been “morally corrupted” by reading four-letter words. He submitted as evidence a citizen complaint sheet witnesses said was in existence at the school at the time of the original complaint but was not used.

He questioned Golden Davenport and Morrison attempting to get them to define precisely why they were in favor of banning the book and under what circumstances they would support the banning of other books.

Daniel Lacasse, the school board’s lawyer, asked questions designed to show the board had good intentions and had acted systematically with educational goals in mind in banning the book and that they were carrying out their duties as elected school board members.

Coles gave a copy of an unidentified book wrapped in a plain brown wrapper and a list of dirty words found in it to Mrs. Davenport who said she wouldn’t want her daughter to read it without permission. The book turned out to be a copy of Love Story which her daughter had signed out of the high school library around the time of the censorship.

Coles read aloud a sexually explicit passage from Ulysses, banned in the US until 1933. He elicited Mrs. Davenport’s opinion that a book containing antisemitic comments such as The Merchant of Venice should probably be banned.

Coles summoned Davenport’s fourth husband, John Boyce of Topsfield. He testified that while they were married she had used four-letter words to him and in front of their children. “She had a general vocabulary of four-letter words,” he said adding he did not believe she had changed her vocabulary. Mrs. Davenport had testified that she had not used four-letter words to great extent.

Thomas Golden said he believed Glasser could have written the book using different language such as that used by Stephen Crane or Erich Maria Remarque in their books about the Civil War and World War 1. He said he believed a student should be able to read a book based on his maturity. Golden said the board had banned the book only because of parent complaints. It was not submitted to a new review policy passed during the summer because the decision had been made, he said. He said he would have to see a book before deciding if it should be banned when Coles asked to state how many times four-letter words would have to be used before he objected to the book.

Coles said A Rumor of War, a Vietnam War era book which he said contains many more four-letter words than 365 Days is also In the high school library.

John Morrison defended the school board’s decision saying it is its proper role to encourage students to use acceptable language even though students regularly use four-letter words or are exposed to them. He said it should be all right for a school board to ban a book without reading all of it.

He said he was only joking when he had commented at a teacher’s meeting that teachers objecting to the board’s ruling shouldn’t forget who pays their salaries. There will be no reprisals against teachers testifying against the ban he testified.

Judge Conrad Cyr declined to hear a renewed request that a film crew from Virginia be allowed to film the proceedings. He said he would hear the motion Jan 5, said Grady Watts of Bennett Watts Bennett productions which is filming a one-hour TV documentary on book censorship in the US for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The hearing will resume at 9:30 am.

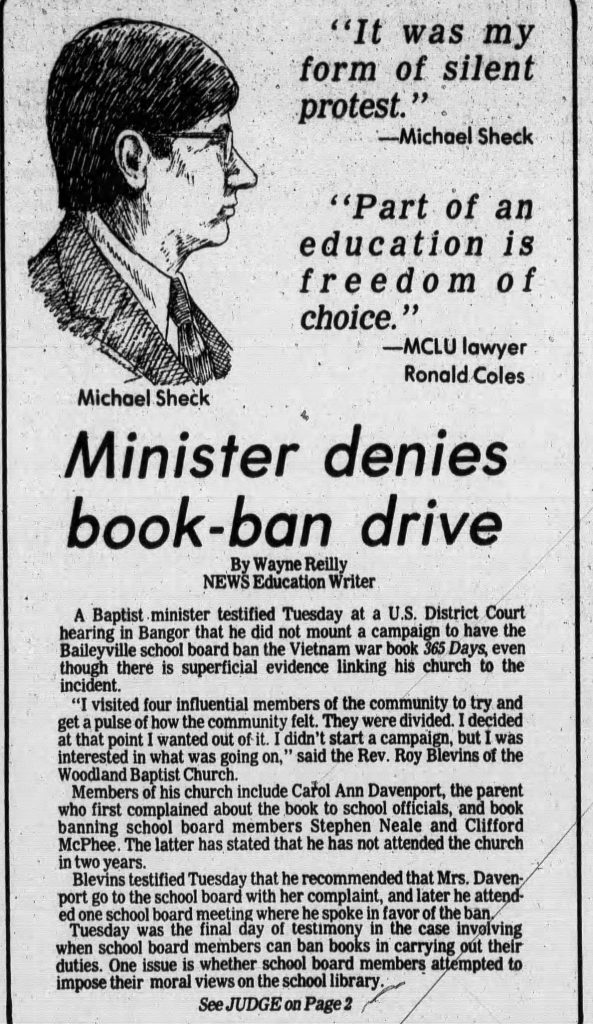

Testimony on day two of the hearing included the school committee’s defense and the role of a local minister on the controversy.

Bangor Daily News:

By Wayne Reilly NEWS Education Writer

A Baptist minister testified Tuesday at a US District Court hearing in Bangor that he did not mount a campaign to have the Baileyville school board ban the Vietnam war book 365 Days even though there is superficial evidence linking his church to the incident. “I visited four influential members of the community to try and get a pulse of how the community felt. They were divided. I decided at that point I wanted out of it. I didn’t start a campaign but I was interested in what was going on,” said the Rev Roy Blevins of the Woodland Baptist Church. Members of his church include Carol Ann Davenport, the parent who first complained about the book to school officials and book banning school board members Stephen Neale and Clifford McPhee. The latter has stated that he has not attended the church in two years. Blevins testified Tuesday that he recommended that Mrs Davenport go to the school board with her complaint and later he attended one school board meeting where he spoke in favor of the ban.

National newspapers reported on the school committee members testimony:

Tampa Bay Times-December 22:

By JON FLEMING United Pratt International

BANGOR, Maine

A mother, whose complaints have prompted a high school library to remove a Vietnam war book, testified Monday she objected to the use of “questionable words.” Carol Ann Davenport, whose daughter attends the high school in Baileyville, said: “I glanced through it to see what was in it,” before asking a school committee to remove it from library shelves. Thomas Golden, chairman of the school committee in the town of 2,000 near the Canadian border, testified: “If I were a soldier lying in bed and found out my leg had been amputated, I don’t think I would use those words.”

The Bangor Daily reported that board member Clifford McPhee and Superintendent Ray Freve testified on day two:

Freve indicated that the school board does not normally pick out new books although once it denied a request for an art book because of its high price. He said that the story of 365 Days could have been told without the objectionable expletives. Board member Clifford McPhee said he did not believe that students should have freedom of choice in a library. He said he had not read the entire book and that he did not think that is necessary before making a decision on whether to ban the book.

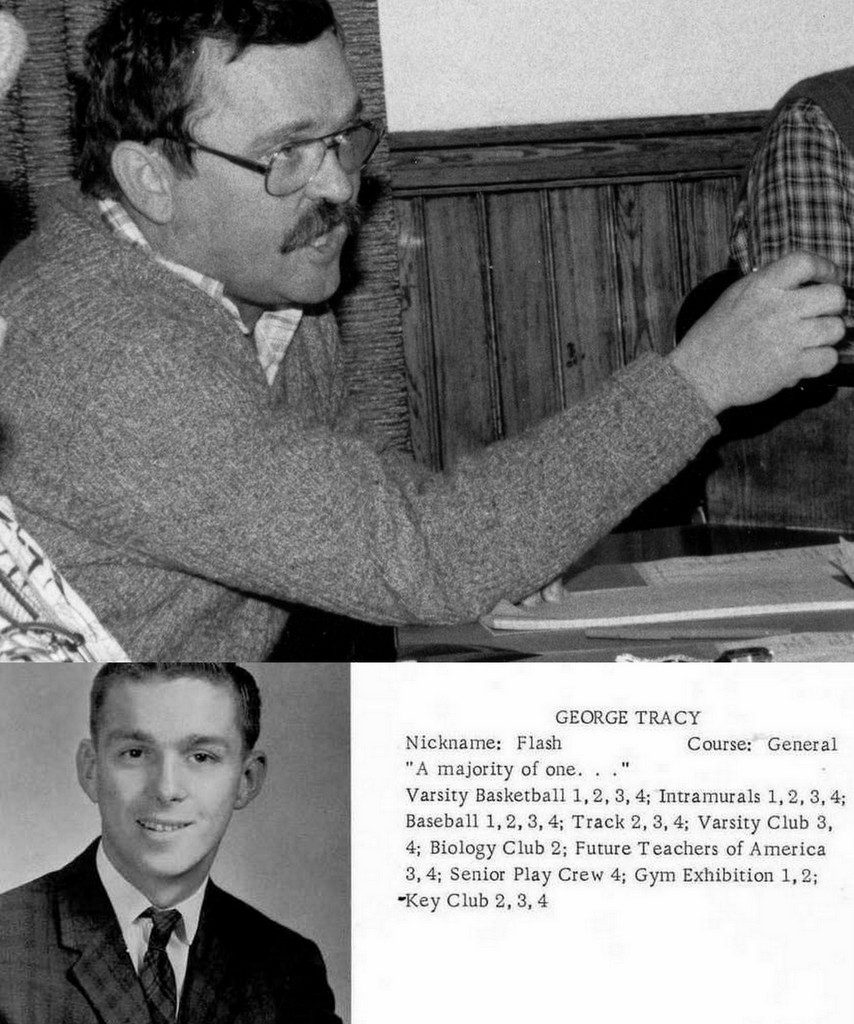

Many national papers focused on the day two on the testimony of two Calais veterans, George Tracy and John Nichols, later known to Calais residents as John Cashwell and Mayor Cashwell after he was elected to that office. Tracy, who graduated from Calais High School in 1964 was a decorated Marine infantryman who fought on the border between North and South Vietnam, the DMZ, an area of intense combat. Cashwell had been a helicopter pilot with many combat missions to his credit.

One of the lawyers questioned Cashwell: “You’re a veteran of the Vietnam War?”

Cashwell: “Yes, I flew helicopters there”.

Lawyer: “Where did you train?”

Cashwell: “Fort Rucker. Rhymes with that word we’re not supposed to say.” [Added with thanks to Bill Bridgeo, Calais City Manager at the time]

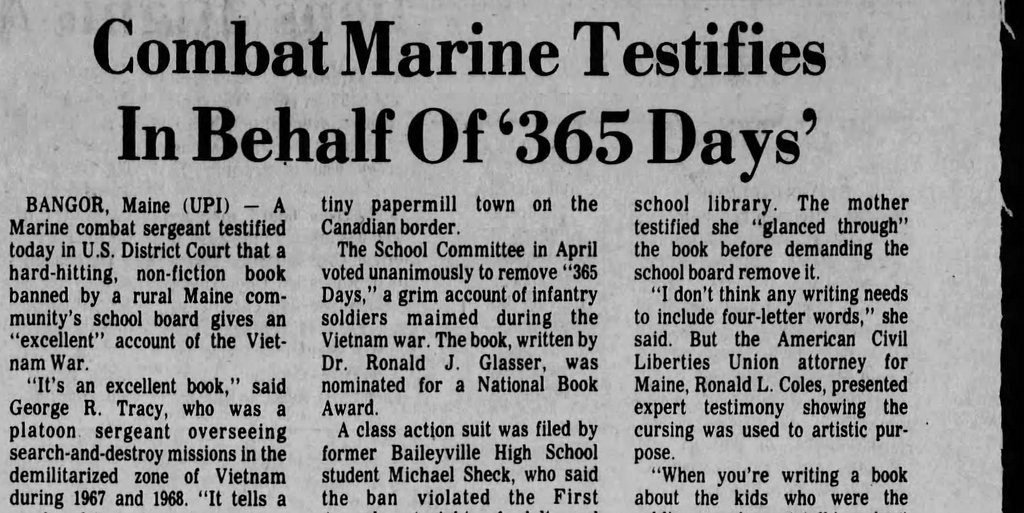

The Times Argus of Barre Vermont reported Tracy’s testimony:

Combat Marine Testifies On Behalf Of 365 Days

BANGOR, Maine (UPI) – A Marine combat sergeant testified today in U.S. District Court that a hard-hitting, non-fiction book banned by a rural Maine community’s school board gives an excellent account of the Vietnam War. It’s an excellent book, said George R. Tracy, who was a platoon sergeant overseeing search-and-destroy missions in the demilitarized zone of Vietnam during 1967 and 1968. It tells a good and true story of what happened. Tracy said an accurate portrait of combat requires the use of harsh language. Almost every sentence (used by soldiers in combat) had the word in it, Tracy said. But under cross-examination, Tracy said the language in the book that offended school committee members would not be appropriate while sitting at the table with your family or in mixed company. He also said he felt the book should be available to high school students. The court proceedings were expected to end later today.

Court proceedings ended that day with the expectation that the judge would issue an order on the temporary injunction which asked that the book be returned to the library pending final hearing. There was much speculation in the national press that Judge Cyr would order the book be temporarily placed on the restricted shelf.

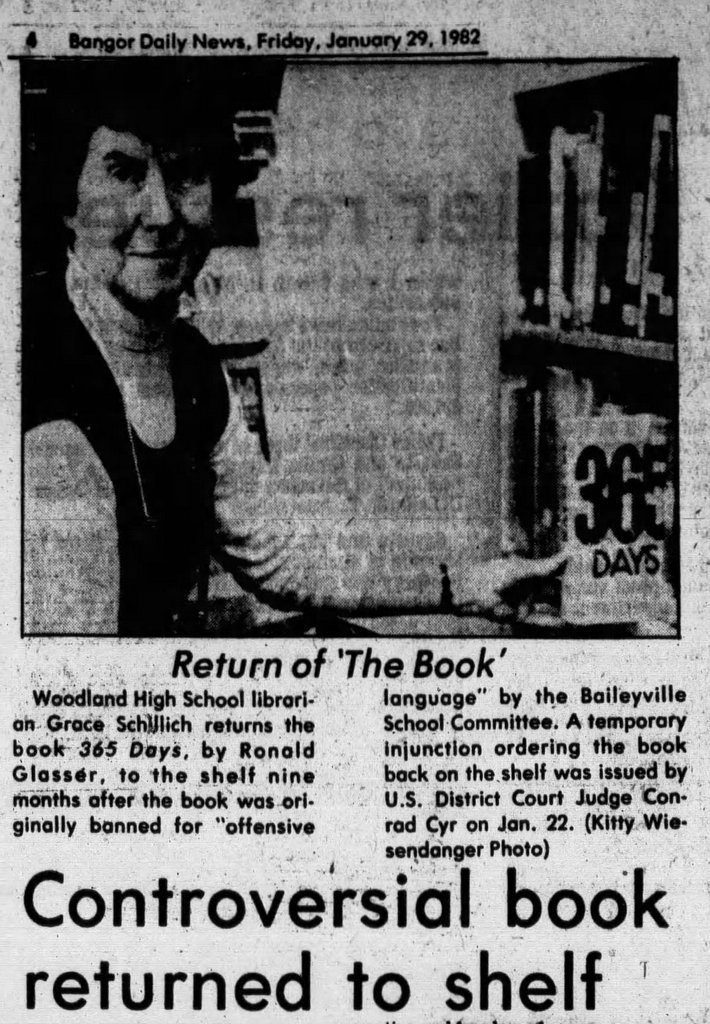

Judge Cyr issued his order in January, returning 365 Days to the library without restriction. The Bangor Daily reported on January 25:

The desire of school officials to suppress controversial ideas has been an important issue in most other book banning cases. But Cyr made it clear it is impossible to draw the line between ideas and vocabulary. “As long as words convey ideas, federal courts must remain on first-amendment alert in book-banning cases, even those ostensibly based strictly on vocabulary considerations. A less vigilant rule would “leave the care of the flock to the fox that is only after their feathers” said Cyr who issued a preliminary injunction Friday ordering the banned book back on the shelves at the Baileyville school.

People have a right to receive information just as they have the right to speak their minds under the First Amendment, explained Cyr. The right extends to students in secondary school libraries which have been variously described as “forums for silent speech” and “warehouses of ideas” by other federal judges.

Cyr issued “a historic decision; I believe it will have tremendous influence not only in Maine but in the United States,” said Ronald Coles, Maine Civil Liberties Union lawyer for the students and parents who filed the complaint.

This was not technically the end of the case. The School Committee was entitled to a full hearing before the Court, although the language in Judge Cyr’s 34-page decision certainly signaled he was not sympathetic. Editorial opinion from around the country was mixed. The Minneapolis Star opined that the decision was “a welcome ray of sanity” while the Bangor Daily news suggested Baileyville request help with legal fees from the Maine Municipal Association and fight on but the town had had enough. Judge Cyr had given a nearly unambiguous signal to the town that further proceedings would avail them of nothing. Taking the advice of their attorneys the school committee settled the case by agreeing to a court order which barred the Baileyville School Committee from removing the book from the high school library.

From an historical perspective the case simply confirmed the oft proven truism that banning books, regardless of the motive, is always counterproductive. In the spring of 1980, 365 Days was collecting dust on the shelves of most libraries and sales were few. That all changed when the Baileyville School Committee voted 5-0 to ban the book. Soon the book was flying off library shelves and bookstores all over the country couldn’t keep it in stock. It was almost certainly read more after 1981 than in the decade after its release. It is also rather ironic that “the word”, which according to one school board member in 1981 was “pornographic to some children” is today deemed acceptable on political flags and signs on flag poles and front lawns in full view of all children of all ages. There can be little question that the quality of public discourse has changed recently and not for the better.