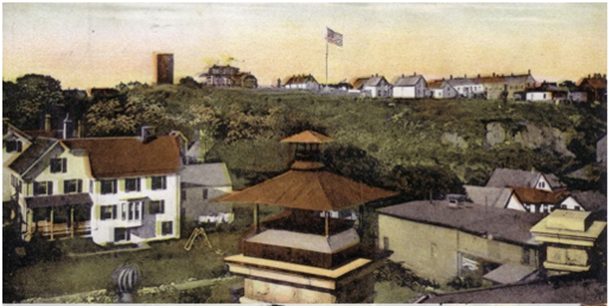

We don’t, of course, have any photos of Downeast Maine from 200 years ago; but there is the above painting of Passamaquoddy Bay which represents an artist’s conception of the bay some years later. Eastport can be seen to the left in the background, which is appropriate as Eastport was the major city in the St. Croix Valley in the 1820s. It had a population of nearly 2,000 compared to Robbinston’s 424 and the 418 residents of Calais, and Eastport was the economic hub of the St. Croix Valley.

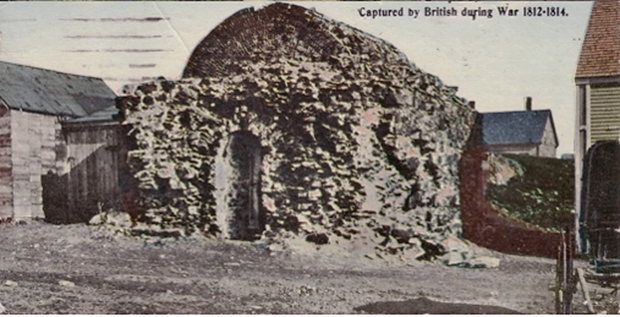

Further, Eastport had been the center of national attention since July 11, 1814 when, as reported in the national newspapers:

Eastport (Maine) was taken on the 11th inst. by 7 British ships of war, without firing a gun. The fort was commanded by Major Putnam, mounted 6 24 pounders and had 70 or 80 men.

The implied criticism of Major Putnam’s fighting spirit was not lost on the folks Downeast who suffered through four years of a sometimes-brutal British occupation. Consider the case of two Lubec lads who in 1815 were entrapped by the British for the purpose of setting a marker on the costs of resistance.

From the Lancaster Intelligencer, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, June 17, 1815:

British Barbarity and Villainy.

We have seen a letter lately received from the eastward, which states, that, on the 12th of May, two young Americans, belonging to Lubec, in Maine, had been whiped [sic] 200 lashes, by the British, at Eastport, after having been entraped [sic] by a savage British Colonel, of the name of Harris. This Barbarian directed 2 of his Sergeants to disguise themselves in Citizens’ clothes and go about the island to endeavor to persuade some of the Americans to agree to take over some British Soldiers. The two young Men became their Victims. The Sergeants retired, threw off their Citizens’ dress, assumed the garbs of British Soldiers, and went into the boat. A party in ambush, for the purpose, rushed from their concealment and seized the young Men. They were sentenced to 300 lashes, 200 of which were inflicted by these Monsters of cruelty on a public wharf, in presence of hundreds of People.

But, what added to the villainy and barbarity of the transaction was, that the Mother and Sister of one of the young Men were driven to the place, at the point of the bayonet, and compeled [sic] to witness the dreadful scene! The savage Colonel appeared to take pleasure in their misery, and aggravated their wretchedness by bestowing on the poor Sufferers the vilest and most opprobrious epithets.

We learn, verbally, that these unfortunate Victims of British perfidy and cruelty fainted, before the 200 lashes were completed; and that the Savages continued the execution of the sentence, while they were in this state! Of all the nations of the world, England claims to be the most humane and civilized. In reality, she is by far the most inhuman, barbarous, and brutal.

Even when the occupation ended in 1818, the Downeast’s economy took years to return to “normal” if that term could even be applied to an economy that relied on smuggling which itself relied on ever changing tariff rates and levels of enforcement. We browsed news articles from the era to see what life was like for folks Downeast back in the 1820s and what the Eastport Sentinel and national newspapers reported about life Downeast.

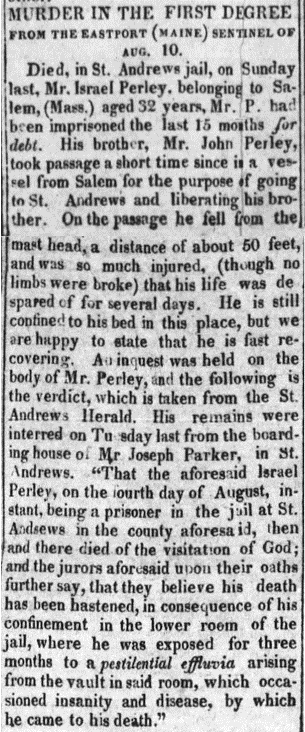

One of the main differences between now and then were the consequences of making bad financial decisions. Your creditor could have you incarcerated in “debtor’s prison” until you paid the debt—which may seem counterproductive from the creditor’s standpoint but was intended to put pressure on your family to come good for the debtor’s obligations before the debtor succumbed to the horrid conditions in such places of confinement as the St. Andrews jail, pictured above in recent photos.

From the Kentucky Gazette, Lexington, Kentucky, 26 September 1822:

MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE

FROM THE EASTPORT (MAINE) SENTINEL OF

AUG. 10.

Died, in St. Andrews jail, on Sunday last, Mr. Israel Perley, belonging to Salem, (Mass.) aged 32 years, Mr. P. had been imprisoned the last 15 months for debt. His brother, Mr. John Perley, took passage a short time since in a vessel from Salem for the purpose of going to St. Andrew’s and liberating his brother. On the passage he fell from the mast head, a distance of about 50 feet, and was so much injured (though no limbs were broke) that his life was despaired for several days. He is still confined to his bed in this place, but we are happy to state that he is fast recovering. An inquest was held on the body of Mr. Perley, and the following is the verdict, which is taken from the St. Andrews Herald. His remains were interred on Tuesday last from the boarding house of Mr. Joseph Parker, in St. Andrews. “That the aforesaid, Israel Perley, on the fourth day of August, instant, being a prisoner in the jail at St. Andrews in the county aforesaid, then and there died of the visitation of God; and the jurors aforesaid upon their oaths further say, that they believe his death has been hastened, in consequence of his confinement in the lower room of the jail, where he was exposed for three months to a pestilential effluvia arising from the vault in said room, which occasioned insanity and disease, by which he came to his death.”

Another concern of many seafaring families was the possible loss of loved ones and/or their ships and cargoes to pirates. Typical of the many reports of piracy is one In the Eastport Sentinel on October 19, 1822 of a ship bound for Havana:

That off Coloridas she was taken by a piratical schooner apparently from Havana. She was plundered and set on fire, the captain and crew were abused in the most shocking manner, one man was killed, the mate was hanged three times, the Captain’s feet were tied together and he was thrown overboard where he remained until he almost drowned. They were kept six weeks by the pirates who gave them the sloop they arrived in and ordered them to return to their country.

As brutal as the pirates were, they expected no quarter if captured and were often hanged on the spot even if sometimes innocent. William Vance Jr. of Baring shipped as a doctor on the vessel which was detained under suspicion of piracy and though he had taken part in no act of piracy was hanged with the rest of the crew after only a cursory inquiry into the vessel’s activities.

From the Lancaster Intelligencer, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 29 May 1819:

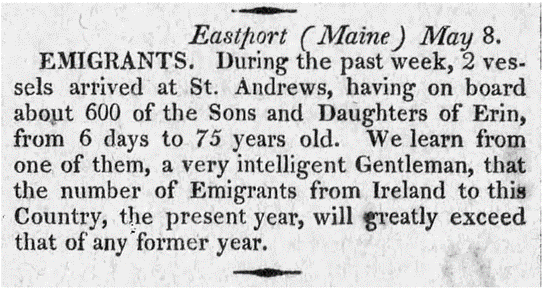

One issue which stands the test of time is immigration, which in the 1820s was dominated by the “Sons and Daughters of Erin,” the Irish. Many began arriving in St. Andrews of the War of 1812 and soon large numbers of them began arriving in Eastport. The reaction in Eastport was defensive in the beginning, enacting ordinances to levy fines against ships’ captains who “dumped” immigrants in the town–who then were likely to become public charges. The Eastport Sentinel reported incidents of violence such as a July 1821 attack in which “four gentlemen were attacked by several Irishmen armed with clubs. Three of them were instantly knocked down and severely beaten; the fourth parried the blows with an umbrella.” The paper went on to say the Irishmen exclaimed “damn Yankees” as they fled and “There can be little doubt that Murder, horrid premeditated Murder was the object of these abandoned ruffians.”

However, by 1822 the town’s attitude seems to have changed, as the July 6, 1822 edition of the Sentinel reported:

Emigrants

Hundreds of Irish Emigrants have landed in this place in the last 24 hours. Our streets are literally filled with men, women and children.

Their appearance, generally, is respectable. They appear to show much satisfaction in stepping on the “land of liberty flowing with milk and honey.” We welcome them to our shores and hope they will realize their most sanguine expectations. They must however remember that it is by honest industry they can obtain milk and honey.

From The Morning Post. London, England, 18 September 1824:

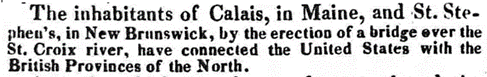

One Calais item which made national headlines in the era was the building of the first bridge on the continent to connect British and American territory. The bridge was and is the Milltown bridge.

From the Lancaster Intelligencer, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 26 July 1825:

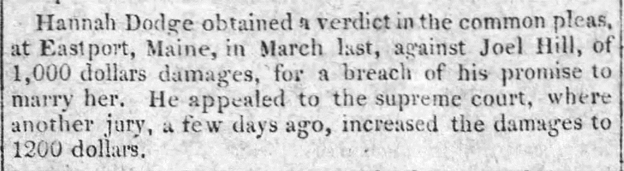

The Courts in those days also regularly levied fines and sometimes jail sentences for failure to keep the sabbath and for sexual relations out of wedlock.

Sometimes it was hard to believe news reports such as the story in The United States Gazette of Philadelphia which reported on 24 June 1828:

Singular Providence.—Mr. Dyer, a cooper, hearing the cry of a child about 8 years old which had fallen overboard at Eastport, (Maine) jumped into the water and was bringing it to shore, when a boat from the English brig Nimrod came to him, when he was nearly exhausted and relieved him from his burden He returned to his work, and when the lad was brought to life, soon after, he was informed it was his own son.

In other items of local interest, the Passamaquoddy Bank of Eastport was nearly always on the national list of “Broken Banks,” and the Eastport Sentinel regularly carried notices offering rewards for the capture of Massachusetts soldiers who had deserted from Fort Sullivan or inmates who had escaped from the jail in Machias.

We’ll end with the burial instructions left by an Eastport sea captain who wanted to go to his maker as befitted a man of the sea.

From the Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England, 9 February 1824: