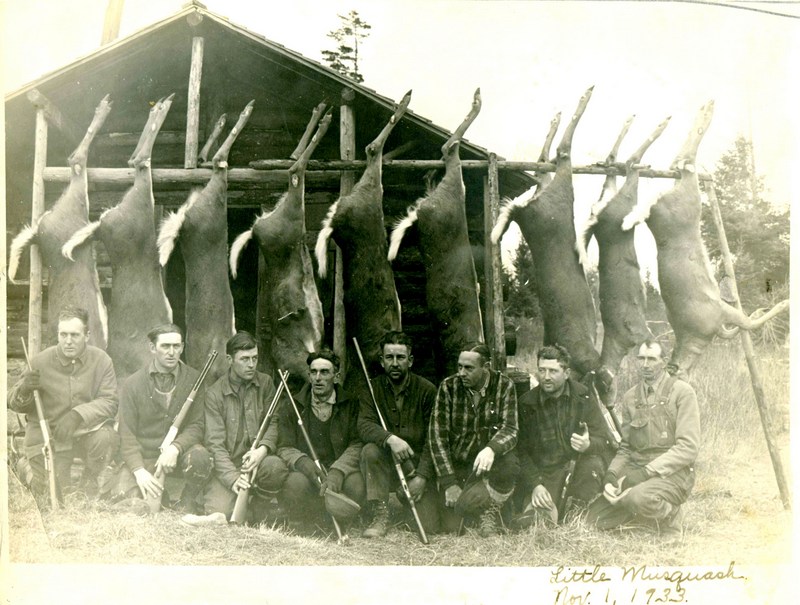

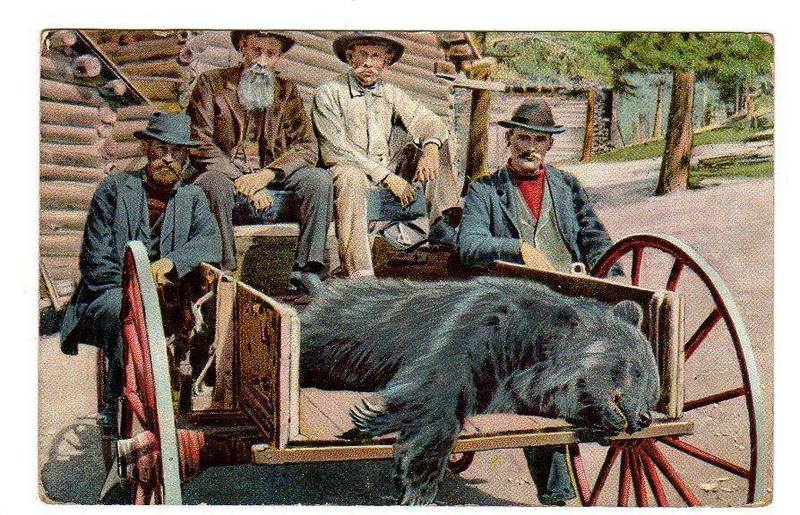

Historical Trivia Question: In what year was hunting season in Maine cancelled and why? The answer is below – but first, as it is now hunting season, some of our favorite hunting photos.

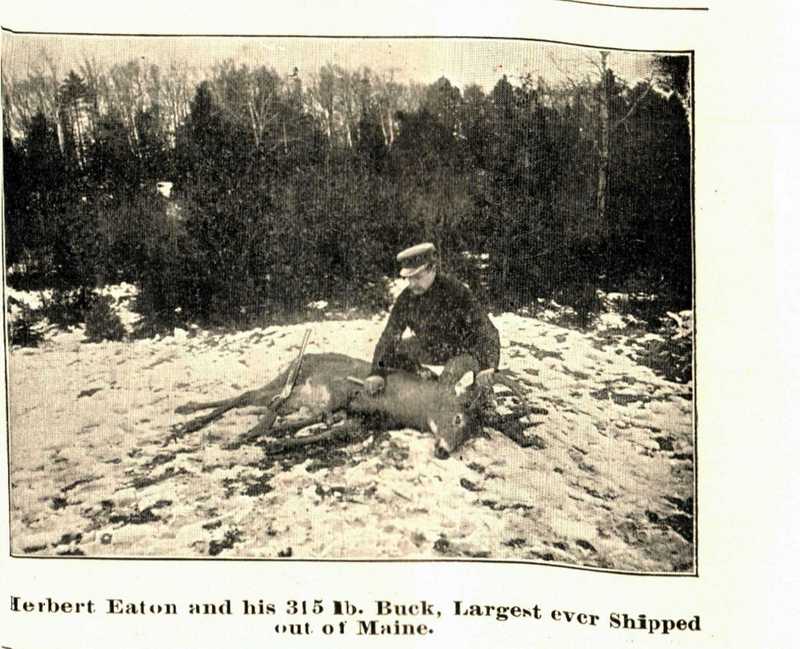

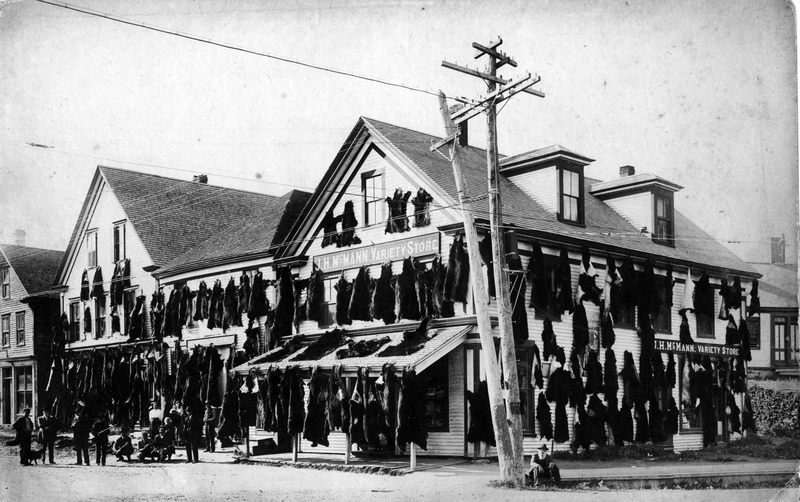

Probably this record has long since been surpassed. The photo is from the late 1880s. Herbert not only shot deer but relatives and friends. In the 1880s, angry, drunk and completely unprovoked, he shot his brother for no apparent reason, severely wounding him and then turned his gun on a close friend, Sam Kelley, and killed him. Being a wealthy lumber baron Eaton eventually paid a $1000 fine but kept his hunting license.

A hunter safety course may be in order here…

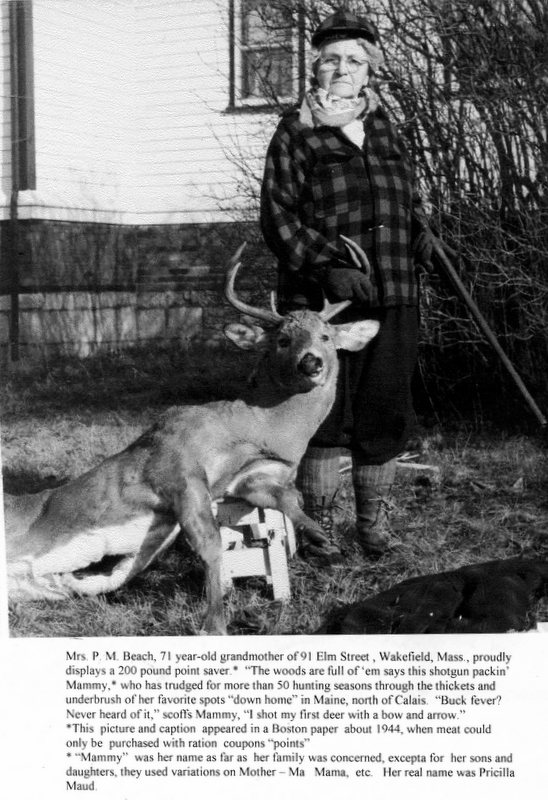

Even grandmothers took to the woods during deer season.

This one may have nothing to do with hunting. There was a wildly popular dance back in the 20s and those Milltown folks would certainly have taken to such a dance craze. They could be a bit wild at times.

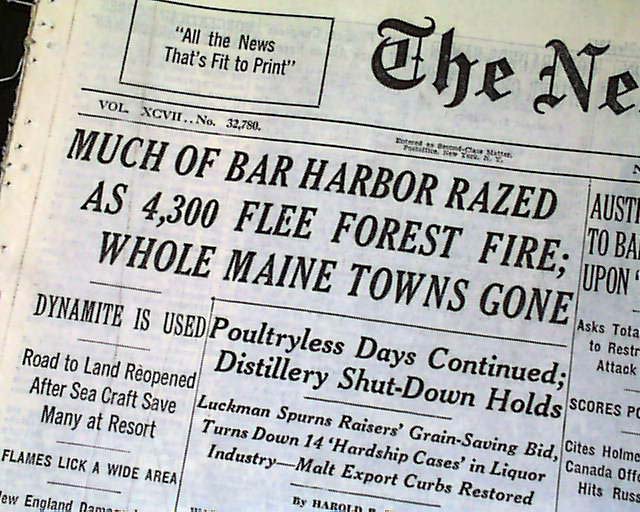

Now the answer to the trivia question.

The year hunting season in Maine was cancelled was 1947, known as the year Maine burned. Drought conditions and a very hot summer produced a tinderbox in the Maine woods. Throughout the state forest fires raged but none was quite as serious as the Bar Harbor fire pictured above. Not only were thousands of acres of forestland burned but the fire didn’t respect city and town limits, destroying resorts, homes and taking many lives.

Given the conditions in the woods, Maine cancelled the hunting season. The Calais National Guard and many locals deployed to Bar Harbor and fought the fires. Some who couldn’t help in Bar Harbor were the residents of Alexander and Cooper. They had their own fire to contend with as the Township 19 blaze destroyed nearly 300 acres. Thanks to John Dudley, we have an account of that fire, with which we will close. Gordon Lord, then a teenager, gives an especially interesting account of his first experience as a firefighter.

THE OCTOBER 1947 FOREST FIRES IN TOWNSHIP 19 ED

October 1947 is considered the worst time in Maine forest fire history. A period of 108 days with no measurable rain started in mid-July leaving vegetation, wells, and streams bone dry. October 5th was the first day of Fire Prevention Week in Maine. That day the temperature reached 80 degrees in Bangor and five fires were burning in Washington County, including the Centerville fire. A hundred acre fire at Bar Harbor had burned all weekend, but was contained. Within hours all that changed when the wind started blowing. Bar Harbor and York County suffered the most and are remembered by many. The Centerville fire eventually consumed 19, 970 acres. Statewide that month, sixteen people lost their lives and 2500 were made homeless. 205,678 acres of forests, fields and pasture were burned.

The Maine fire that burned the most acres was the Miramichi fire of October 7, 1825. There also was a Miramichi fire in New Brunswick on the same day and that is how the Maine fire got its name. The Canadian fire burned forests, farms, and several villages. The Maine Miramichi fire burned 832,000 acres of forestland.

Man starts 80% of the forest fires, and lightning starts the rest. The cause of the Centerville fire was smoking. Of 533 fires in unorganized towns in 1947, 12 were caused by lightning, 109 had unknown origins, and the rest were caused by man.

Forest fire detection and fighting have changed greatly in the past century. Between 1910 and 1920 forest fires averaged 205 acres in size, fifty years later, each fire averaged 2.5 acres. It was in the teens that the state started having lookout towers connected by telephones. By 1947, airplanes were used to spot fires and radio information to the firefighters.

The purpose of this paper is to look at two fires of October 1947 that occurred in Township #19. Unfortunately, the Department of Conservation threw away all the records of all 1947 fires in the mid-eighties, so our official record of these fires is brief. We do have some great memories to share and some memories of other fires at the time.

OFFICIAL RECORD: The Forest Commissioner’s Report for 1947 – 48 states:

Township #19 ED on October 22 a fire started by lightning eventually burned 10 acres. *

Township #19 ED on October 25 a fire started by campfire eventually burned 275 acres. **

Township #19 ED on October 25 a fire started by unknown eventually burned 10 acres.

MEMORIES OF THE #19 FIRES:

I thank those who shared these memories. Their names are in bold print. It is amazing how much detail was remembered after a half century. These are much more interesting than the Official Record.

*The first three accounts are about the October 22 fire.

Cecil Keen tells about the night, “My brother Horace and I were out to the Frank Day Field looking for the Bar Harbor fire. We could see the glow in the sky. Then Horace saw a fire in #19. We went to my father’s place and called Everett Grant, he was the fire warden down in Marion. He told us to get a crew and go in and put out the fire.” Those who arrived at the fire site about 2 AM the next morning included Harold Vining, Phillip Day, Harold Sadler, Wesley Ireland, Alden Keith, Horace, and Cecil. They were on the scene three days and nights with no break. “We were ten days getting that fire out. It started from lightning, there had been an old ripper of a storm the night before.”

“Everett got a 6×6 army vehicle from Cole Bridges, Elbridge McArthur drove it. He’d bring us food and pumps and hose, we had to put a pole bridge across Northern Stream. We had a hose from the stream to the fire, about half a mile, filled our 5 gallon Indian pump cans.”

“We slept on the ground. Women made the food, sent it in on the truck. We were fed better than at home. We couldn’t use the pumped water for coffee, it tasted of gas. Wes Ireland found a spring for coffee water. Once when Wes was coming back in the dark, Horace tried to scare him from behind a tree. Wes set down the pails, took out his jackknife and said, “All right, Mr. Fire Bug, I’ve got you now.”

This fire was east of the 19 Road, between Spectacle Lake and the Cooper line. Cecil’s pants were so shredded that a man from East Machias asked him if he’d been clawed by a bear! He remembers there was no legal deer hunting season because of the dry conditions that year. He also remembers that Everett Grant was “liberal with the hours.”

Bill Hatfield was at that fire and added these names Cecil Hatfield, Everett Dwelley, and Glenwood Sadler. Bill recalls that “Wes Ireland kept the campfire going and the coffee pot hot. Men kept complaining that the coffee was weak. Wes finally put a pound of coffee in a 10-quart pail and boiled it. And it was so terrible they had to dilute it.”

“Another thing I remember was a fellow from Jacksonville who gathered dry pine branches one evening to keep the fire going. He had quite a large pile when we decided to put it all on the fire at once. Several of the men were sleeping near the fire. When it got too hot, they began to wake-up and turned the air blue with profanity while we stood back in the shadows and laughed. Wes Ireland was sleeping with his feet to the fire. His shoes got hot and he got up, but couldn’t stand on them. He got on his hands and knees and crawled away from the fire and went back to sleep.”

Alder H. Keith, Sr.’s account as told by his children Alden and Dorothy Nickerson. “He was staying out there on that fire for nearly a week, and when they finished mopping up every last spark, the fire warden told the men that they could all go home. It being late in the evening, Dad decided to head for camp (home) right through the woods. I remember him telling that it became pitch dark, as he was deep in the woods and that he headed toward the tower light on Cooper Hill. During his trek through the woods he sometimes fell into a wet bog hole or running brook. At no time was he ever afraid, he always said that wild animals are more afraid of you than you of them. Eventually he came out at Earl Frost’s blueberry field there on Cooper Hill and down the road to Cathance Lake and back to camp. No one would have followed my father on such a journey in the middle of the night, but this was his territory where he was brought up as a young man. He relished every tree in that forest.”

**The 275-acre fire, started by a campfire, was at Joe Hanscom Heath. That is west of the 19

Gordon Lord:

In 1947 when a major forest fires hit Bar Harbor, we had our own fire to tend to. Smoke from a fire back in the woods of Township 19 was sighted and Bill Cushing began rounding up able bodies, both boys and men, to help fight the fire. We arrived about two miles from the Crawford line where we found a group ready to move into the fire sight. Wardens issued hand pump Indian tanks. We filled the tanks up and headed west toward the smoke. We walked perhaps a quarter of a mile when we came to a huge heath. Now we could see plainly the smoke and prior to getting all the way across the heath, about three quarters of a mile across we saw the fire on the tree tops. Several of us boys, were lagging behind, our bodies struggling with the wicked load on our backs. Half way across the thick, soft, hard walking heath we decided to ease our load. When no men were looking, we would squirt some of the water onto the dry heath. I only had about 25 percent of my water left by the time we could feel the heat from the fire.

It was mid afternoon when we got to the fire and found the fire not raging as we expected although it was burning good. There was a brook nearby to refill our hungry tanks and no one was the wiser, about our loss of water. We fought the fire until 10pm when we went to a “safe place” to take a nap. After we were asleep, they awakened us and told us to get up quickly and move out because the fire had us nearly surrounded. That done and after another nap on the cold ground, (it was October), we grabbed our tanks and started off toward the fire. At least it would be warm there. When we arrived we found a larger group had arrived and those crews had now surrounded the perimeter of the fire. We were there 6 or 7 days moping up. Good use was made of Calais garage owner Cole Bridges’s army surplus 6 by 6 all terrain world war II surplus vehicles. They were great for carrying in fire fighting equipment, meals and transportation for the fire fighters.