In the late 1800s Eastport was one of the busiest seaports on the east coast, a prominence it owed to a tiny silver fish packed in a small silver can about the size of an iPhone. Steamships similar to the Cumberland pictured above sailed between Boston, New York, Eastport, and St. John a couple of times a week.

The steamships filled their holds with millions of cans of Eastport sardines bound for the Atlantic seaboard markets and beyond and carried passengers between Downeast Maine, St. John, Boston, and New York. When the passengers arrived in Eastport, they could connect with the river steamers which took them to the head of the tide at Calais and St. Stephen.

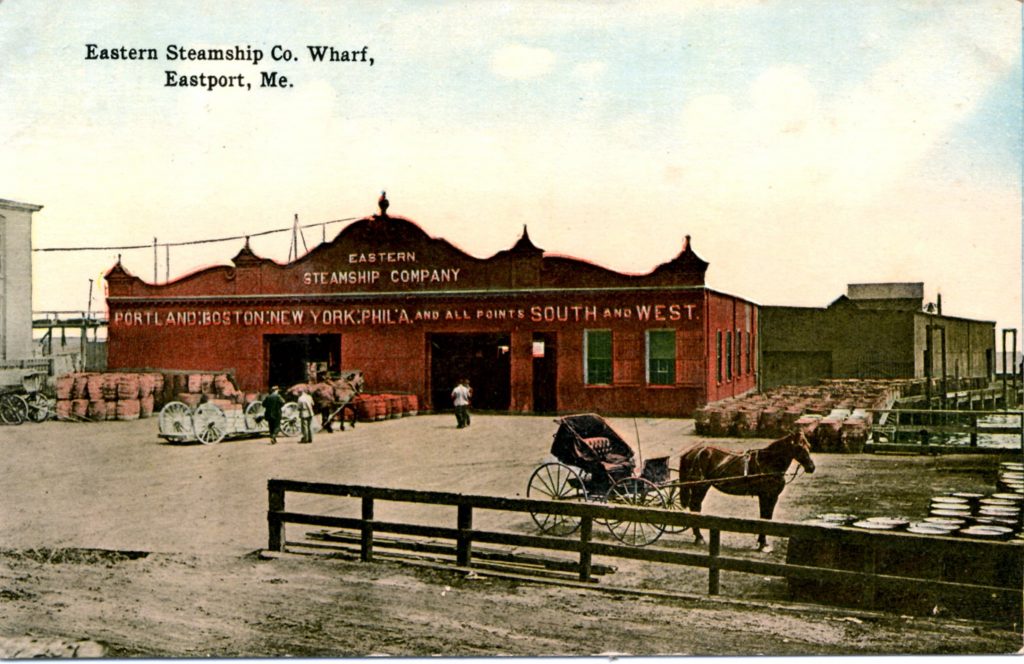

In the early years the Eastern Steamship Company dominated the commercial and passenger trade from their Eastport wharf; but in the late 1880s a New York concern built a large freight depot in Eastport known as the “New York Wharf” and put a large, newly-built, propeller-driven steamship named the Winthrop on the route.

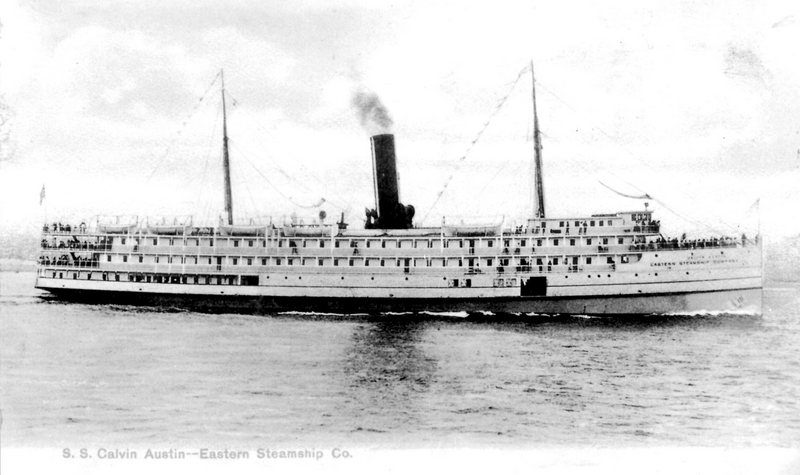

We do not have a photo of the Winthrop but it was probably similar to the Calvin Austin pictured above, a later propeller-driven steamship which sailed the Boston-Eastport route after the Winthrop. The Winthrop was said to be “wide, fast and handsome” with a “heavy booming whistle which would wake the dead” and this feature was especially important to the Winthrop, given its fate. She was built at a cost of nearly seven million dollars in today’s money which, as events transpired, turned out to be a poor investment for a couple of reasons: She operated from the outset at a loss and the Winthrop came to an untimely end on June 13, 1893. On that day, a fire broke out in the ship’s hold as she was approaching Passamaquoddy Bay from St. John and the crew was unable to control the fire. In what one report called “A Race With Death” the captain, instead of giving the order to abandon ship, decided to make a run for the dock at Eastport and ordered “full speed ahead” even though by the time the ship rounded the back of Campobello Island and entered Head Harbor Passage the ship’s main deck was hot from the fire below. Passing Indian Island, a mile from the Eastport waterfront, a fog obscured the ship from view of the shore but the ship’s “heavy, booming whistle” could be heard sounding continuously, warning of trouble to everyone on the waterfront. Miraculously, the captain managed to dock the vessel.

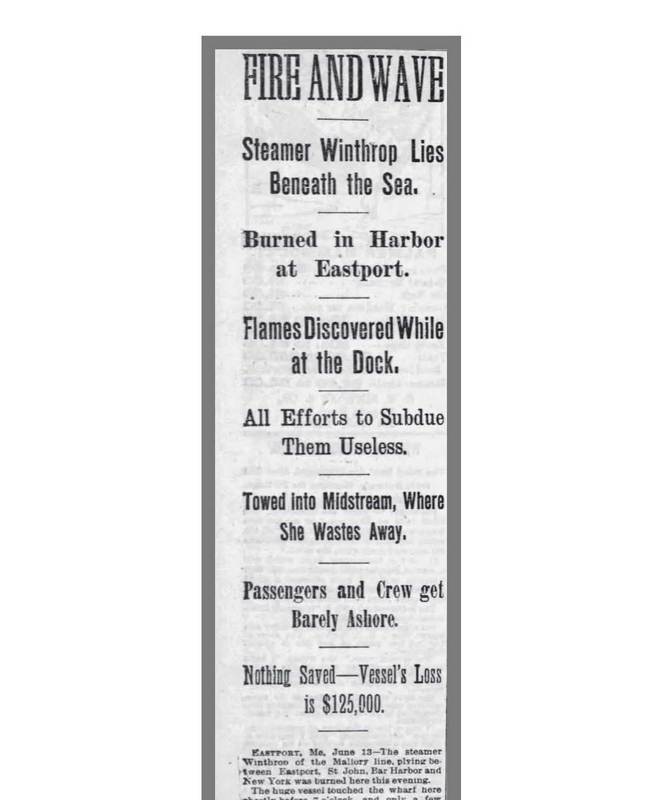

From the Boston Globe June 14, 1893

The Berkshire Eagle, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, June 14, 1893:

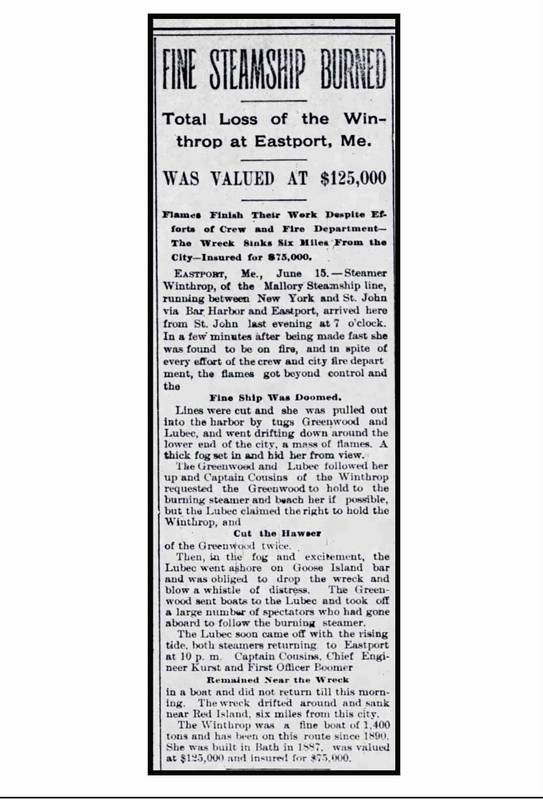

Total Loss of the Winthrop at Eastport, Me.

WAS VALUED AT $125,000

Flames Finish Their Work Despite Efforts of Crew and Fire Department

The Wreck Sinks Six Miles from the City Insured for $75000.

Eastport, Me., June 15. Steamer Winthrop, of the Mallory Steamship line, running between New York and St. John via Bar Harbor and Eastport, arrived here from St. John last evening at 7 o’clock. In a few minutes after being made fast she was found to be on fire, and in spite of every effort of the crew and city fire department, the flames got beyond control and the Fine Ship Was Doomed. Lines were cut and she was pulled out into the harbor by tugs Greenwood and Lubec, and went drifting down around the lower end of the city, a mass of flames. A thick fog set in and hid her from view. The Greenwood and Lubec followed her up and Captain Cousins of the Winthrop requested the Greenwood to hold to the burning steamer and beach her if possible, but the Lubec claimed the right to hold the Winthrop, and cut the hawser of the Greenwood twice. Then, in the fog and excitement, the Lubec went ashore on Goose Island bar and was obliged to drop the wreck and blow a whistle of distress. The Greenwood sent boats to the Lubec and took off a large number of spectators who had gone aboard to follow the burning steamer. The Lubec soon came off with the rising tide, both steamers returning to Eastport at 10 p. m. Captain Cousins. Chief Engineer Kurst and First Officer Boomer remained near the wreck in a boat and did not return till this morning. The wreck drifted around and sank near Red Island, six miles from this city. The Winthrop was a fine boat of 1.400 tons and has been on this route since 1890. She was built in Bath in 1877 was valued at $120,000 and insured for $75000.

We cannot explain why the tug Lubec would have twice cut the tug Greenwood’s hawser, a thick towing cable, but it certainly seems odd the two tugs would have chosen such a time to engage in a commercial dispute over a burning ship drifting dangerously about the harbor. We imagine newspaper reports in the Eastport Sentinel explain this rather unseemly episode.

The arrival of the Winthrop at the Eastport waterfront is described as follows:

The Winthrop’s captain succeeded in docking his burning ship and safely disembarking his passengers and crew members. By that time the flames had leaped through the deck. The Winthrop’s lines were cast off and a tug towed the burning ship a short distance offshore so that danger from fire to the Eastport waterfront could be averted. The flood tide carried the steamer up around Green’s Point and she burned to the water’s edge off Broad Cove. Only one life was lost when a crew member suffered a heart attack.

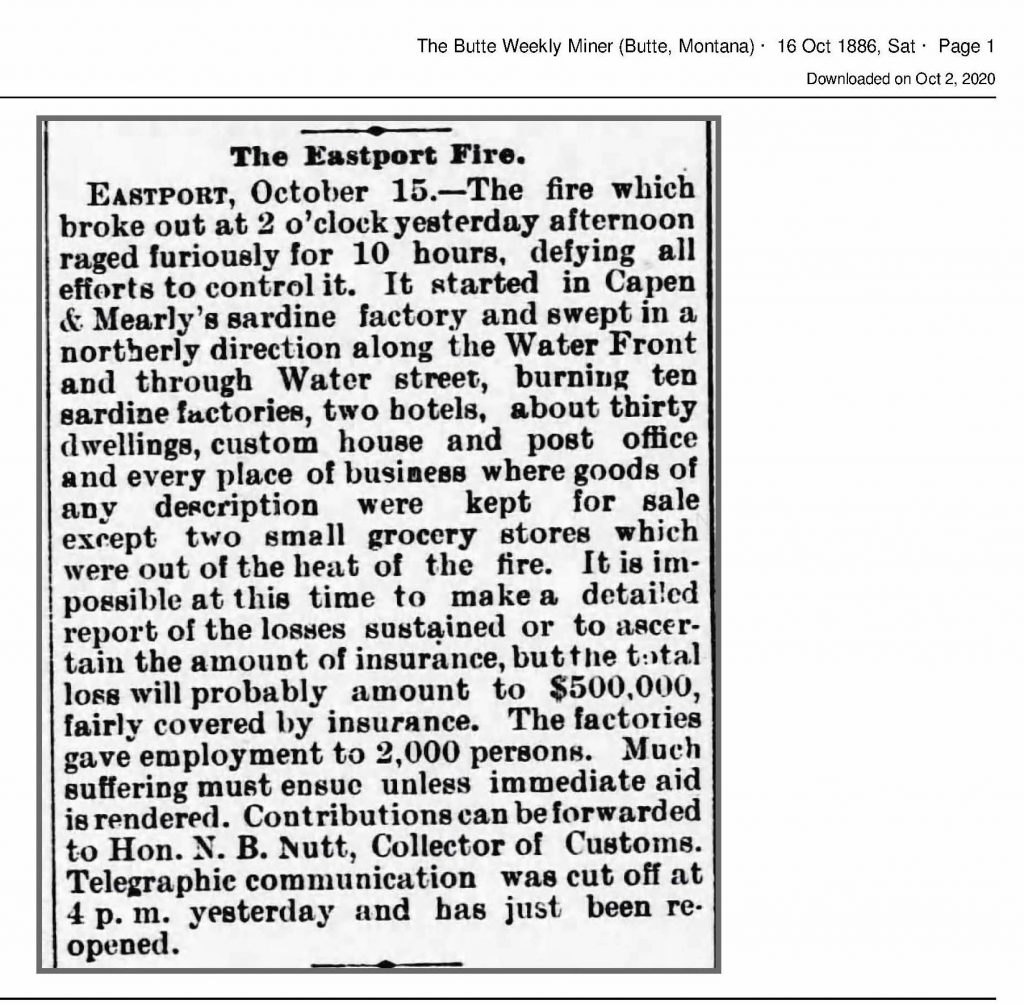

The dramatic description of the travails of the Winthrop as a ‘Race with Death” may have played well in the press, but we think it unlikely the captain of the Winthrop got a “Captain Sully” reception from Eastport locals. In 1886, just seven years earlier, nearly the entire waterfront of Eastport and some of the city had been destroyed by fire. The 1886 devastation is pictured above. When the burning Winthrop arrived at the dock and newly rebuilt waterfront, the city was presented with another potential catastrophe, and 1886 was certainly fresh in the City’s memory. The 1886 fire was widely reported throughout the nation even in landlocked Butte, Montana.

The Butte Weekly Miner, 16 October 1886:

So devastating was the fire that for a couple of days there was concern in the country that the City of Eastport had been entirely destroyed.

The Post Star, Glens Falls, New York, October 16, 1886:

IS EASTPORT DESTROYED?

Uncertainty of the Result of the Big Fire There

Merchants Anxious.

New York, Oct 15.

The information received to-day by merchants in this city about the condition of Eastport, Me., having been so meagre, much alarm is felt by those who have interests there. It is feared that the whole town has been destroyed by fire. The wires are deserted by the operators, and there has been no time for letters to arrive. Eastport does a large business with this city in the packing of fish, especially sardines. It is roughly estimated that the town sends to New York 130,000 cases of canned and packed fish every year. A large supply is also sent to Boston. At the Western Union telegraph office a reporter called on the superintendent of the New England lines, but he had nothing to report.

The signal service office also reported that while they were enabled to get reports this morning from Portland they were unable to communicate with Eastport, and ascribed this to the storm which was working its way to sea on the Gulf of St Lawrence. It is understood that Eastport has been a favorite place for many who desire temporary out of town homes near the Canadian border without going outside of the United States, and as it is reported that the principal hotel has been destroyed, some little anxiety is felt for those who may have remained there to enjoy the pleasures of the Indian summer near the seaside.

While the ship burned harmlessly and sank six miles from the Eastport waterfront, a repeat of 1886 was not improbable given how quickly fires spread in those early days, and the fate of the city may well have depended on the direction of the wind.

Readers may be wondering by now what all this has to do with “sunken” treasure. One need only recall the riches which went to the bottom of the Atlantic when the Titanic hit an iceberg in 1912 for the answer. The staterooms of Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus and others contained a king’s ransom in jewels, gold and silver–200 million dollars of which have already been recovered from the wreck. While the rich and famous of the Titanic were described at the time as “Robber Barons” and those in the Eastport sardine trade dismissed as “herring chokers,” who can say what riches lie on the ocean floor of Passamaquoddy Bay six miles from Eastport just off Red Island? The news reports say nothing was saved; the passengers left with only the clothes on their backs. Therefore, it stands to reason the wreck holds in its bowels all the passenger’s possessions and a wreck that large should be easy to find even after 135 years though we admit we can’t find Red Island on a map of the bay. Still someone should be able to find Red Island and the treasure. The Historical Society would like to help but we continue to focus our treasure hunting on the gold and silver at Moneymaker Lake.