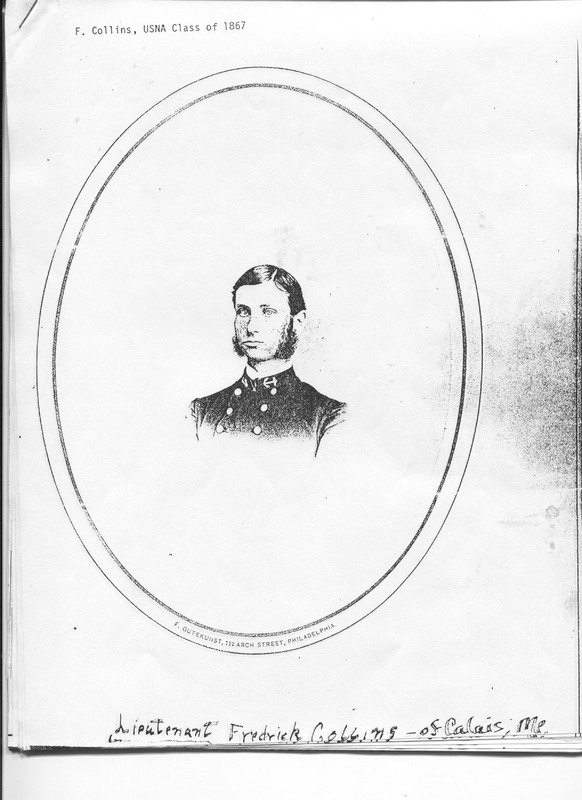

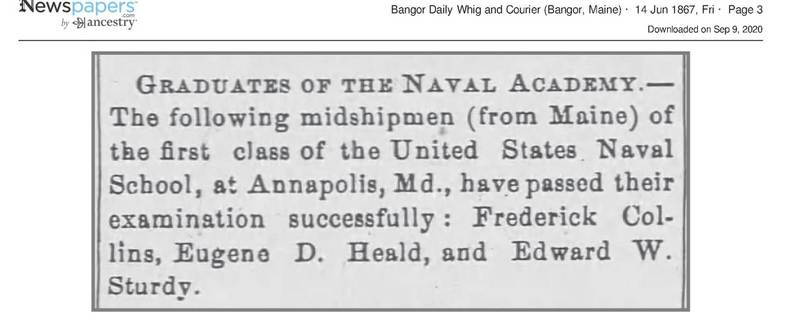

One notable Calais native who has been forgotten over the passage of time is Frederick Collins pictured at left at his graduation from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1867. Perhaps “native” does not strictly apply to Fred Collins as he was born in Milbridge in 1847, but his mother Charity and her five children, Fred being the youngest, moved to Calais in the early 1850s very soon after the death of her husband Bradbury Collins, one of Washington County’s first sheriffs.

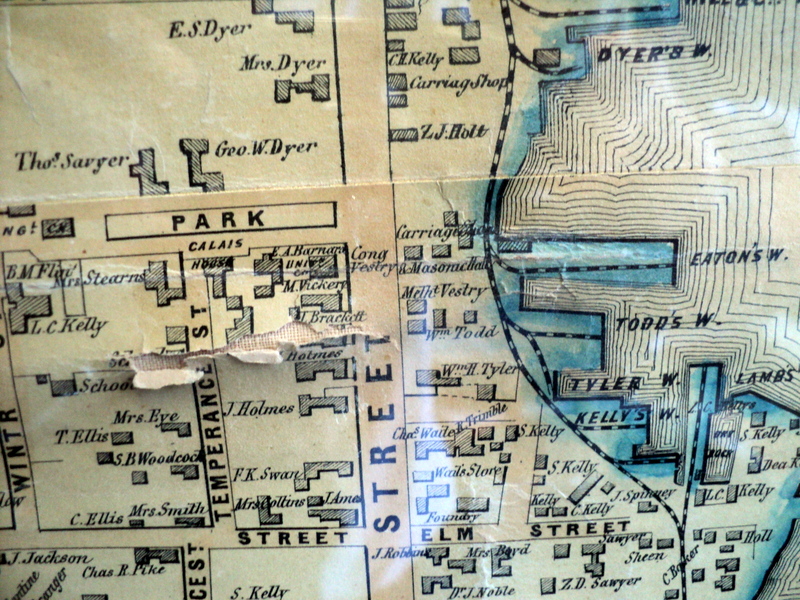

We do know the family had moved into a house across from the park at the corner of Temperance Street and Germain Street by 1856 where there is now a church, and she lived there until her death in the 1880s when she willed the property to her son Charles. According to an article in the Calais Advertiser Fred was educated in Calais schools and early in life gained an “enviable reputation among scientific men”. He certainly appears to have been a child prodigy and destined to make his name on the national stage.

By 1867, at age 20, he had graduated from the Naval Academy at Annapolis. It is not surprising he gained a coveted appointment to the Academy which then, as now, requires both accomplishment and influence. The map of 1857 above shows among his neighbors Doctor and Mrs. Holmes who had recently built the beautiful “Holmestead” on Main Street, now the property of the Historical Society. Mrs. Holmes was Vesta Hamlin Holmes, sister of the Vice-President of the United States Hannibal Hamlin at the time Frederick Collins was admitted to the Naval Academy. Further, Noah Smith, a Calais attorney who lived in a cape at what is now the entrance to Marden’s, was the Secretary of the Senate in Washington during Lincoln’s first term. Calais fought far above its weight in the political arena back in those days.

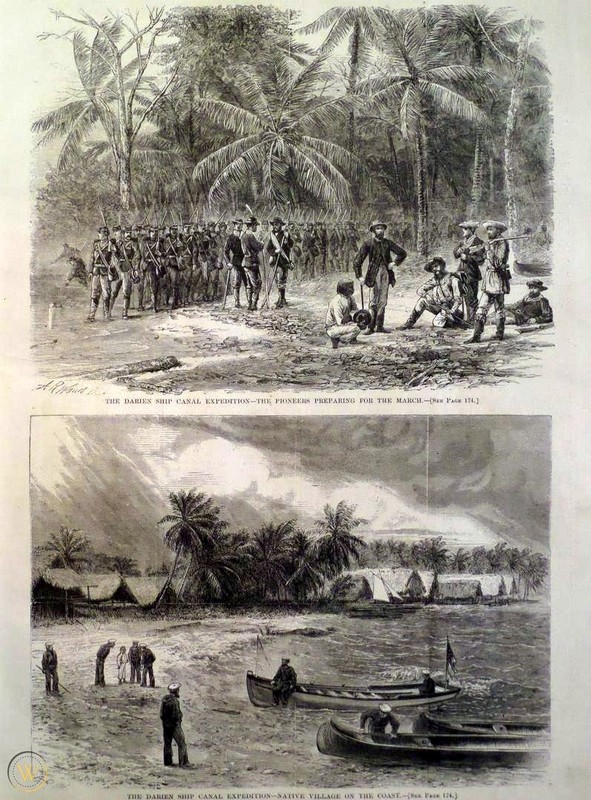

Collins was soon a rising star in the Navy, commanding surveying expeditions on the coast and sailing throughout Europe; but his most important service to the country involved locating the most advantageous route for what was then called the Inter-Oceanic Canal. The major powers of the world all agreed a ship canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific through Central America would not only be advantageous but was absolutely necessary to global trade and development. There were places in Central America where the Atlantic and Pacific were a mere 40 miles apart so naturally expeditions were sent to explore these possible canal routes, and a fierce competition between nations developed to build the canal. President Grant felt strongly that the United States could not allow a European nation to have control over the canal, and early in the 1870s the Navy began exploring possible routes over the Isthmus. Frederick Collins was selected to participate in the early expeditions and later in 1874 to lead one of the most important explorations of the prospective routes. Above is an article regarding his assignment as leader of the expedition.

It took several months to complete the expedition, and the difficulty of the terrain and the climate challenged even those on the expeditions who were veterans of prior South American exploration. The heat was intense and humidity was usually above 95%. When the sun was not draining the men’s energy the clouds opened with torrential rain; a foot or more could fall in a couple of hours causing mudslides and swollen watercourses. The terrain was hilly and covered with dense vegetation. The men were nearly always sick with tropical diseases, malaria being the most common, yellow fever the most lethal; and the mosquitoes were so thick it was often impossible to keep a candle lighted at night as the insects swarmed the candle and by self-immolation extinguished the flame. It was not uncommon for men to suffer temporary insanity in the tropical jungle although Collins reports none on this expedition and while Collins survived the hardships of the expedition his experiences in the tropical jungle would result in his early death.

Collins filed a lengthy report and testified before the Inter-Oceanic Commission after returning from the expedition. While he tried to maintain the appearance of impartiality it became clear he felt the route he had surveyed was not the best choice, and he favored the “Nicaragua” route which had been surveyed contemporaneously by another U.S Naval expedition. This route became the choice of the U.S. government, but, as we know, the French were in favor of a sea level canal across Panama, and the French had an ace in the hole—the builder of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand De Lesseps. The French began construction first but failed to complete the canal and in the end Grant’s dream of U.S. sovereignty over the Inter-Oceanic Canal became a reality when the United States bought the French Concession and completed the canal in the 1900s.

Collins’ health was seriously compromised by his expeditions in Central America. He continued his naval service but in a different role. Still in his early 30s he became an influential spokesman for the Navy and was often quoted in the papers on naval affairs. However, his health continued to deteriorate and he died October 29, 1881, not yet 35 years of age, a death which was reported in all of the large newspapers in the country.

Frederick Collins is buried in the U.S. Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis, Maryland. His wife Emma, who he married in Portland, Maine and who survived him by nearly 30 years, is buried beside him. They had one child, a daughter Elise. Had he not sacrificed his health in the service of his country he would surely have risen higher in the Navy and on the national stage. His complete obituary is below:

LIEUT. FREDERICK COLLINS, U. S. N.

Those (and they are many) who have been watching with interest and content the career of Lieut. Collins, were more than shocked to read the brief announcement of his death which appeared in the Army and Navy Journal of last week. Lieutenant Collins, who was born in Calais, Maine, about thirty-five years ago, inherited from his ancestors that peculiar aptitude for his profession which always distinguished him. He commenced early to show great proficiency in his studies, and invariably look one of the prizes at school examinations, usually the first.

In July, 1863, he was appointed to the Naval Academy, and passed through the curriculum of that institution with great credit, graduating third in a class of eighty-seven members, and holding the highest cadet office (that of cadet lieutenant-commander), during the last year of his probation.

After graduating, his first service was in the European squadron at the time of Farragut’s memorable cruise, and his letters home at that period gave good promise of his abilities as a descriptive writer, while the accuracy of his views on the great variety of subjects that arose during an extended journey about the coasts of Europe, indicated a maturity of mind and a soundness of judgment, which are exceedingly rare in so young a man.

Shortly after this we find him one of the chief officers of the first expedition to determine the line of a canal across the Isthmus of Darien. Notwithstanding the fact that he nearly died of Chagres fever, he kept at the work, when able, until its close, and his reports furnish the most valuable portions of the results of that important survey. The letters he wrote to the New York Herald on the subject of the Isthmus surveys are the clearest expositions extant of the purposes and results of that arduous work; and the Geographical Society of New York, appreciating the value of his labors and the lucidity of his views, invited him to address them on the subject. This lecture will now be read again by his many admirers with a melancholy interest, and always with satisfaction and benefit. He never recovered entirely from the effects of this trip, but it did not affect his interest in the service or diminish his zeal and energy in advancing what he considered its true needs. Later, he organized and took charge of another expedition to the Isthmus when he demonstrated effectively that the route on which he had been engaged was not the best for an interoceanic canal.

The excellent work here done, and the clearness of his ideas on all subjects connected with the Navy (always forcibly expressed on occasion), marked Lieut. Collins as one of the most promising of the younger members of that profession; and from the time of his last expedition, if not before, his views were generally sought or eagerly looked for, whenever any matter of special interest was occupying the minds of the officers of the service. The fertility of his imagination as well as the force of his argument and the point of his wit, are well exemplified in his articles in the United Service Magazine, criticizing the prize essay on naval education. Few such evidences of a brilliant mind have appeared in our naval literature. Latterly his selection as a member of the Advisory Board, while still attached to the training ship Saratoga as navigator, was looked upon peculiarly proper; and it is an interesting and solacing fact that his last service was in connection with the reorganization of the Navy, based on the opinions of experienced officers who have its interests most at heart. The short career of Lieutenant Collins is made up of something besides a chronicle of promotions and orders to different ships and in this respect it certainly commands admiration and will inspire imitation. Let us hope that its usefulness may be of some comfort to his widowed mother in Maine, and to the heart broken wife and fatherless children in his later home in Washington.

Articles above transcribed:

INTER-OCEANIC CANAL COMMISSION.

The special Inter-Oceanic Canal Commission have suspended their meetings pending the arrival of Professor Pierce. As has already been stated, this commission will not make a final report on the surveys of the different canal until the return of an expedition that is to make some further surveys on the Napipi route, on the Isthmus of Darien, this winter. The arrangements for this expedition have been for some time quietly progressing, and yesterday the order detailing its officers and assigning the day for its sailing was issued from the War Department.

The expedition will be under the command of Lieutenant Frederick Collins, United States navy, with whom will be associated Lieutenants Joseph G. Eaton, J. T. Sullivan, E. W. Very and S. C. Paine, all veterans in Darien service, under Commander Selfridge, with Assistant Surgeon J. F. Bransford, as medical officer.

These officers have all necessary instruments for the accomplishment of their difficult work with scientific accuracy and a liberal supply of provisions, put up in water-tight packages to protect them against the copious rains of the tropics. The expedition will sail from New York, in the Pacific mail steamer which leaves that port on the 2d of January.

There they will repair on board the United States steamer Canandaigua, whose commanding officer will have directions from the Navy Department to furnish them transportation to the Gulf of Uraba, and provide them with all necessary men and material for the prosecution of the survey. As the bar at present existing at the mouth of the Atrato prevents the passage of vessels of heavy draught the party will be obliged to ascend that river in steam launches and cutters. Having transported the party with their instruments and supplies to the Napipi river, in the vicinity of which their survey will begin, the boats will return to the Canandaigua, which will then sail, with orders to return for the party on the 20th of March. The object of this expedition is to obtain such extensive and definite data concerning the topography along the Napipi line as will enable the commissioners to compare it with that of Nicaragua, which has been much more . . . (end of text)

THE GREAT CANAL.

———

Strong Argument by Lieutenant Collins in Favor of the Nicaragua Route—Great Saving of Time to be Obtained.

———

WASHINGTON, MARCH 6.—The address of Lieutenant Frederick Collins, U.S.N., before the house committee on the inter-oceanic ship canal on Saturday last brought out some points heretofore but little considered that promise to prove difficult nuts, for M. de Lesseps and the promoters of the Panama canal scheme, to crack. Without entering into any consideration of the physical features of the different rival routes, or of the engineering questions involved, Lieutenant Collins devoted his attention to demonstrating the relative inferiority of the Panama route, as compared with the Nicaragua, by a consideration of the prevailing winds and currents of the Pacific Ocean in the vicinity of the west coast of North and South America. The unfavorable character of these winds and currents in the vicinity of Panama for navigation by sailing vessels had long been known, he said, and frequently commented upon as a disadvantage of the Panama route. The subject, however, was but little discussed by the public, and many exaggerated notions were prevalent concerning it. He then referred to the remark so frequently attributed to Lieutenant Maury, that even if the Isthmus of Panama were to be divided by a convulsion of nature, it could never be a commercial highway for sailing vessels. This doctrine, Lieutenant Collins thought, like most other sweeping assertions could be accepted only with qualifications and res-

ervations. His own careful investigation of this subject had led him to conclude that on an average the loss of time in getting from the bay of Panama to a place where good winds would be found would not exceed ten to twelve days if the correct route were followed. Now ten days, compared with the saving that an isthmian canal would effect over the routes now pursued, were a bagatelle, and certainly could not prevent the use of a canal were one open. But, if it could be shown that ten days could be saved by one isthmus route, that must be lost by another, then it became a matter of vital interest in the selection of a location for a canal. He proposed to demonstrate beyond the possibility of a denial that the route via Nicaragua would effect a much greater saving than that as compared with Panama or . . . (end of text)