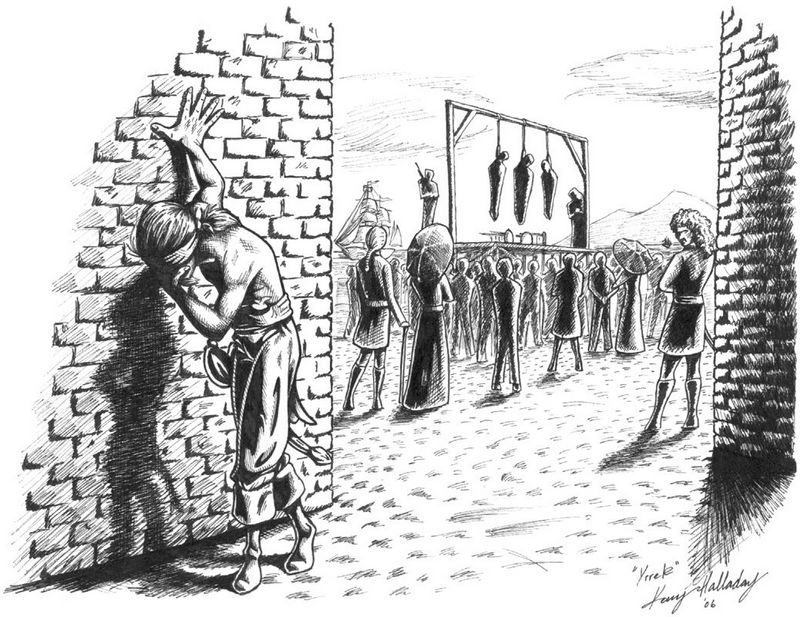

Early doctors in the St. Croix Valley were, on the whole, a pretty unlucky bunch. The first doctor in the area, Dr. McDonald, settled on the Canadian side in the 1780’s. Dr. McDonald didn’t practice much medicine which may have been good for the community, as there is no evidence that he had any medical training. Mainly he tried to make his fortune in lumbering but was not a great success and in the early 1800’s became embroiled in the dispute between the settlers and proprietors on the American side over ownership of Ferry Point in Calais, even claiming under oath, almost certainly falsely that he had settled on the point before Daniel Hill, who is considered Calais’ first settler. While he didn’t fare well in commerce, medicine or the courts, he did avoid the misfortune of being hanged as a pirate which was the fate of Doctor William Vance.

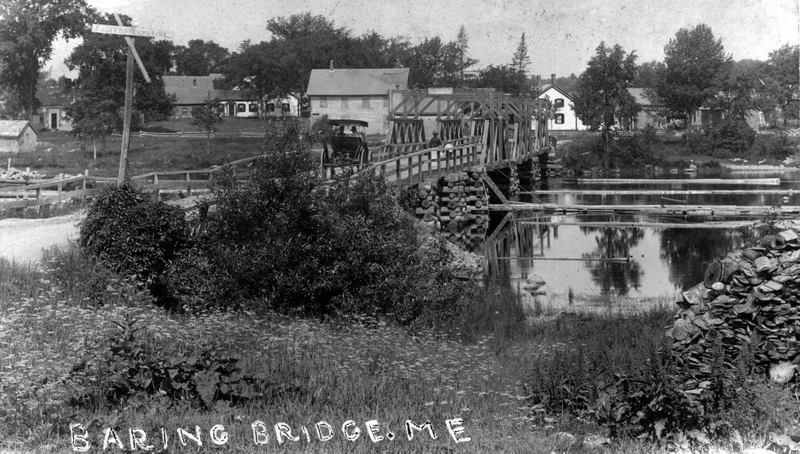

William was the first son of William Vance of Baring known locally as Old Vance. Vanceboro is named after Old Vance, but he’s best known for settling Baring.

Old Vance built the first bridge across the St. Croix in the early 1820s and had many children by many wives—sometimes not bothering to divorce the first before marrying the next. William Jr. was his pride and joy and Old Vance sent him off to Harvard to study medicine. William graduated in 1819 and returned to Calais where he’s listed on the 1820 census; but probably finding Calais a pretty dull place for a Harvard man he soon left with a friend on a ship for the West Indies. The details of the trip are sketchy but there is no question he and his friend became stranded and penniless in the Indies and were desperate for passage back home. Vance agreed to take the position of ship’s doctor on vessel which he somehow convinced himself was an armed English ship but which was, in reality, an armed pirate vessel. His friend was suspicious of the nature of the vessel and refused to tag along, which saved his life. Very soon after leaving port the ship was captured by an authentic British Man of War and the entire crew, including the ship’s doctor, was summarily tried and convicted of piracy and hanged. Old Vance always denied his son had been hanged for piracy and named a subsequent son William who, as far as we know, spent his life on dry land.

St. Stephen’s early doctors had no better luck. Above is a photo of men cutting ice above the Milltown bridge. To the right is the chimney of the water company building on the U.S. side and U.S. Customs. Before the Milltown Bridge was built in 1824 often the only way across the river in the winter was to cross at “Stillwater” just above the rapids in Milltown. Below what is now the Milltown Bridge the current to “Saltwater” as Calais was called in those days was too strong to form solid ice. Above what is now the bridge it usually froze solidly enough to walk across the ice and, as the photo indicates, was a source of ice for the community. For example, in the winter of 1811 when counterfeiter Ebenezer Ball shot Sheriff Downes of Calais the only “burying ground” in the area was in St. Stephen beside the Kirk McColl church. The Downes funeral procession had to walk from Calais to Milltown Maine, cross the ice at Stillwater, and carry the casket back down the Canadian side to Kirk McColl on King Street in St. Stephen. Just a few months before the Milltown bridge was built in the summer of 1824, Dr. Gill from St. Stephen had to attend to an emergency in Calais. He had no choice other than to go to Milltown, NB and across the ice to Milltown, Maine. He drowned in the process.

An even sadder case is that of St. Stephen doctor Louis Weston. Weston was one of the first, best, and most esteemed doctors of St. Stephen, but he too came to an untimely end. All his children, twelve in number, having died of consumption, he became entirely disheartened; and while the last one lay a corpse in his house, he went out in the evening, and by accident or otherwise fell into a cistern of rain water near his door, and drowned.

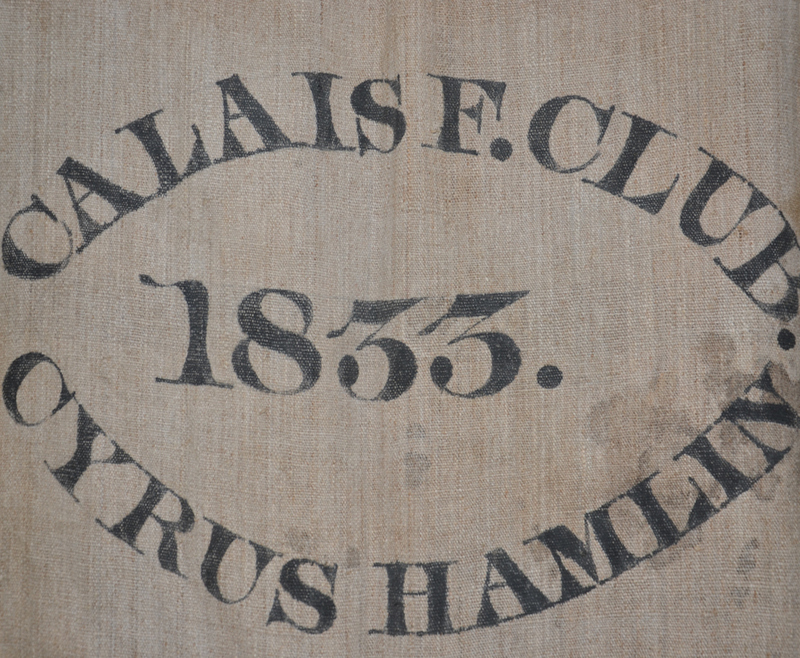

Dr. Cyrus Hamlin was the brother of Hannibal Hamlin, Lincoln’s Vice President for much of the Civil War. In the early 1830s he began his medical practice in Calais at the Holmes Cottage. The burlap bag shown above, which we have at the Holmes Cottage, was required equipment for all volunteer firemen, and Cyrus was in the first Calais volunteer fire company. As most fires were impossible to extinguish, firemen were expected to rush into the burning building with the burlap sacks and fill them with the unlucky homeowner’s possessions. What the firemen could save would likely be the only possessions left to the family. Cyrus unfortunately contacted tuberculosis and suffered more than most of his patients, but he soldiered on as a doctor, once solving a medical mystery in the valley.

Calais Advertiser June 10, 1914 by W.W. Brown:

In the spring of 1835, a large number of persons in Calais and St. Stephen were taken with a mysterious sickness. The symptoms were pain in the back and weakness in the joints and partial paralysis, especially in the lower limbs.

The disease baffled the skill of all the local doctors, among whom were Dr. Whipple and Dr. Hamlin in Calais and Dr. Paddock and Dr. Weston in St. Stephen. No remedies appeared to do any good and it was estimated that over 60 persons died from the strange malady, while many others lived the rest of their lives partially paralyzed.

At this time, Mr. Charles Perkins, one of the principal grocery dealers in Calais was attacked with the disease and he concluded to go to Boston and consult some doctor there. He took the speediest method of getting there which was by stage to Eastport and from there by sailing packet to Boston.

At some previous time, steamers had been running between Eastport and Boston but at this time no steamers were running.

Mr. Perkins began to improve as soon as he left home. When he reached Boston, he consulted an eminent physician named Dr. Morison who after examination and hearing his story told Mr. Perkins that he was satisfied that the people on the St. Croix River were eating something poisonous and advised Mr. Perkins to send home for some samples of groceries and food most used.

Mr. Perkins did so at once and upon receiving the samples took them to a chemist at Harvard College, and upon examination of a packet of brown sugar it was found to be poisonous. The secret was out.

That spring Mr. James Frink, a wholesale grocer at St. Stephen had imported a cargo of sugar from Barbados. It was of nice quality and had been sold to all retail dealers on the river. It had been noticed that only the rich or well to do people had been afflicted, the poor being obliged to use molasses.

At that time most of the medicine in use was of a bitter nature and required to be sweetened, which being done with sugar, the patient was poisoned with every dose of medicine taken.

As soon as Mr. Perkins returned home and informed the public of his discovery, all the sugar was returned to Mr. Frick. He immediately sent to Halifax and had a chemist come to St. Stephen, who after examination pronounced all the sugar to be poisonous.

Dr. Cyrus Hamlin of Calais, being about to visit the West Indies for his health, was employed by Mr. Frick to call upon the sugar manufacturer in Barbados from whom he had procured the sugar. On investigation Hamlin found that the manufacturer had conceived the idea of using lead cauldrons instead of copper, and the syrup from which the sugar was made had remained in the lead cauldrons until it fermented, in which state it absorbed the poison lead.

The manufacturer had become bankrupt and upon learning how many deaths his mistake had caused committed suicide by shooting himself.

When Dr. Hamlin returned home and made his report, Mr. Frick took the balance of the cargo of sugar, valued at six to seven thousand dollars, and hove it all into the river.

Unfortunately, Dr. Hamlin’s own medical condition did not improve, and he left Calais to settle in what he thought would be the more salubrious climate of Texas. He was wrong about the climate and soon succumbed to malaria.

Fort Sullivan, Eastport, Me. (showing Old Barracks)

Early doctors also had another enemy, one they have not defeated to this day: bureaucrats.

While Eastport was under martial law in 1814, Doctor Mowe of Eastport came under the baleful eye of the commander of Fort Sullivan for alleged malfeasance, malpractice and, for want of a better term, being a quack. According to Kilby’s history of Eastport:

While Major Anstruther was in command, an effort was made to banish Doctor Mowe from the island, on the ground that he was a dangerous man, and would be sure to cause the death of all who employed him; and he was threatened with a walk through the streets tied to the tail of a cart, unless he departed. He had a patient at the time who was very sick, and who desired his continued attendance.

Doctor Mowe learned that Lieutenant Duncan, who was friendly to him, would be the officer sent to inquire into the affair; and he prepared to foil his enemy a second time. As soon, then, as he got wind of the movements against him, he sent for the barber, who shaved the patient, dressed his hair, assisted in putting on a well-starched shirt with a prodigious ruffle, and helped to otherwise arrange his person in a manner to show him off to the greatest advantage. The lieutenant, as was expected, was the major’s messenger to Doctor Mowe to order him to desist from practice. The lieutenant loved good wine; and the doctor had procured some excellent “old south side,” which the officer, after being seated a moment in the sick man’s room, was desired to taste. Pressed to drink again, he was finally asked to consider the wine as entirely at his disposal. Thus solicited, he drank of it freely, and praised it at every glass. Conversation ensued, in which the patient bore his share. The sick man looked so well, prepared as he was for the occasion, he talked so well, and defended Doctor Mowe’s treatment of his case so zealously, and the wine, withal, was so good, that the lieutenant went away quite satisfied with what he had seen, and so reported to his superior. Major Anstruther, considering that he had done all that was required of him, declined further interference; though he sent word to the patient that, if he allowed Doctor Mowe to kill him after this, he must thank his own obstinacy. Here the affair ended, and Doctor Mowe was not again molested.

We do need to point out that in the very early days of settlement of the St. Croix Valley there were a couple of decades when there were no doctors in residence, skilled or otherwise. From the 1790s until probably 1810, midwifery and perhaps some medical care were in the very capable hands of the wife of Ananiah Bohanon of Calais. She and others were versed in native medicine and natural remedies which were quite effective for most of what ailed these early settlers, and Mrs. Bohanon gained a reputation on both sides of the border for her skills.