We were asked this week to provide some information to Lura Jackson, editor of the Calais Advertiser, about immigrants to the St. Croix Valley in days past. She is writing an article for this week’s paper. While doing some research we were struck by the how much the St. Croix Valley owes to one particular immigrant group, the Italians, who built much of the public and private infrastructure of the St. Croix Valley. We knew Italian immigrants had built the pulp mill in Woodland and those who stayed in the area had become prominent citizens in Calais and Woodland by the 1920s. However we were surprised to discover that Italians had also, as contract laborers, provided the labor for the Calais, St. Stephen and Eastport water systems; constructed the Washington County Railroad; and the Grand Falls Dam. We feel a short tribute to their efforts is in order.

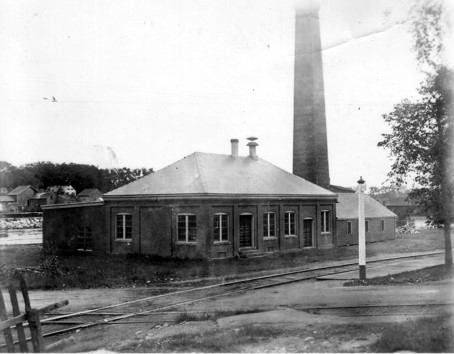

The first reference we have in the historical record to the presence of Italian workers in the St. Croix Valley is 1887, nearly 20 years before they returned to build the Woodland Mill. They were brought here to build the Calais waterworks and pumping station when new. It is still standing, although in poor condition. Ed Boyd, a local historian, writes in his Calais history:

“In the year 1887 the Calais water works was installed in Calais and the pumping station was located in Milltown, Maine close to the bank of the St. Croix River and next to the International Bridge. A crew from Gardiner, Maine (Italian) did the construction work for this project.”

At about the same time, both Eastport and St. Stephen built municipal water systems largely with Italian labor. It appears local labor was not available for such large projects. As late as 1919 when St. Stephen needed to construct new sewer lines the St. Croix Courier reported:

“Work on the new street construction by Water Street commenced Monday morning by excavation of a section of new sewer between Main and Marks Streets, but it has not proceeded very rapidly because of the difficulty in securing men. It is probable that crews of Italians will be brought in for the work.”

Italian workers were, it seems, still in demand for the hard work 40 years after building the local water systems.

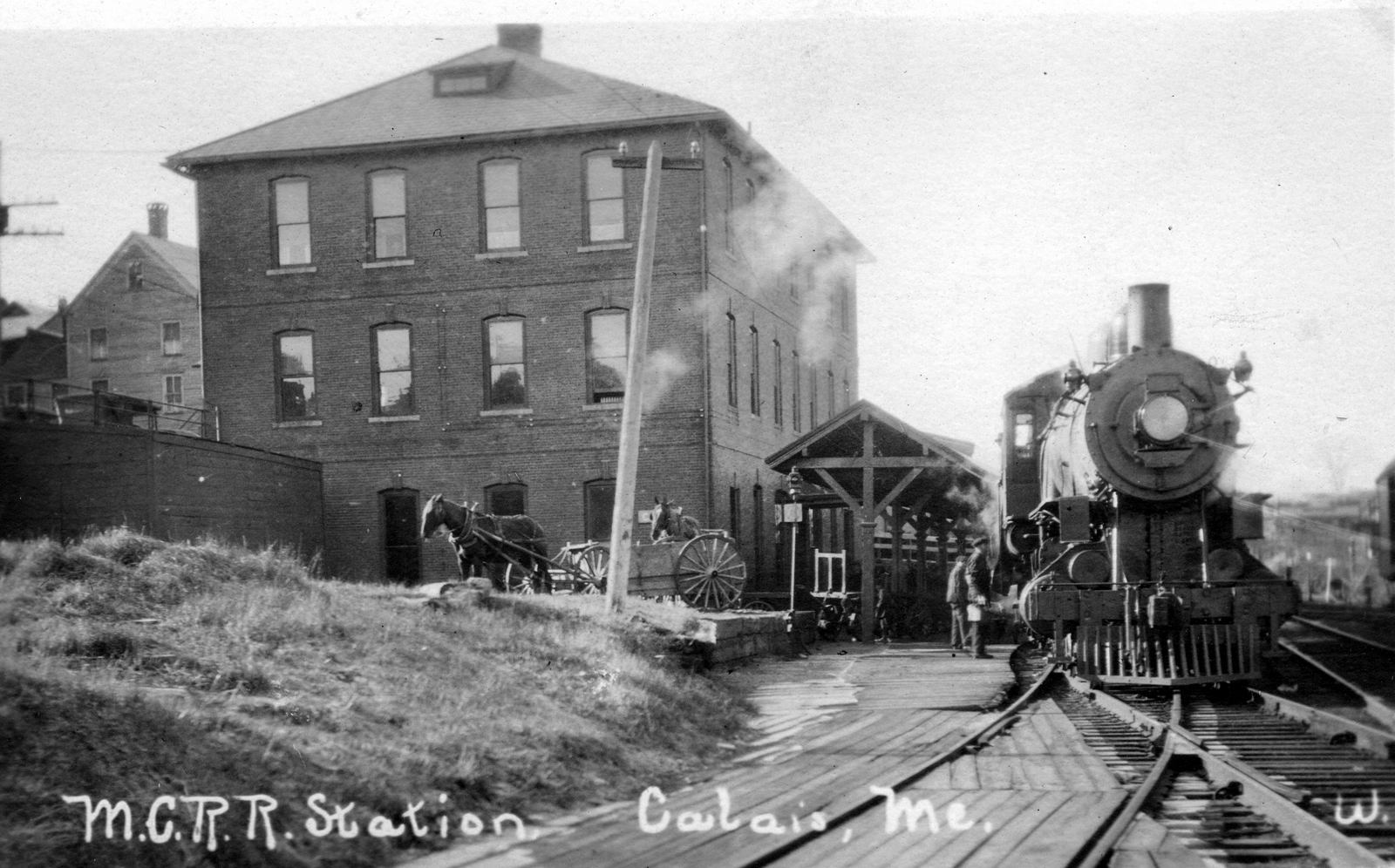

One of the largest projects for which Italian labor can take credit was the building of the Washington County Railroad just before 1900. It would be difficult to underestimate the economic impact the coming of the railroad had for this area. Davis, in his history of the St. Croix Valley, writes:

“In 1893 a charter was issued to the Washington County Railroad Company. It was renewed in 1895, and the county voted overwhelmingly in favor of a bond issue of $500,000 for the purchase of preferred stock. It was another two years before work started, but gangs of Italian contract laborers, who received $1.25 per day, were hard at it in 1897, and the road was finally completed. Within three or four years it was taken over by the Maine Central. 93 trains ran daily, and Calais was no longer dependent on the C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific Railroad] nor was Eastport on the International Steamship Lines. Mail and passenger service was better; sardine packers could ship directly to the Midwest and so won a degree of freedom from Boston and New York.”

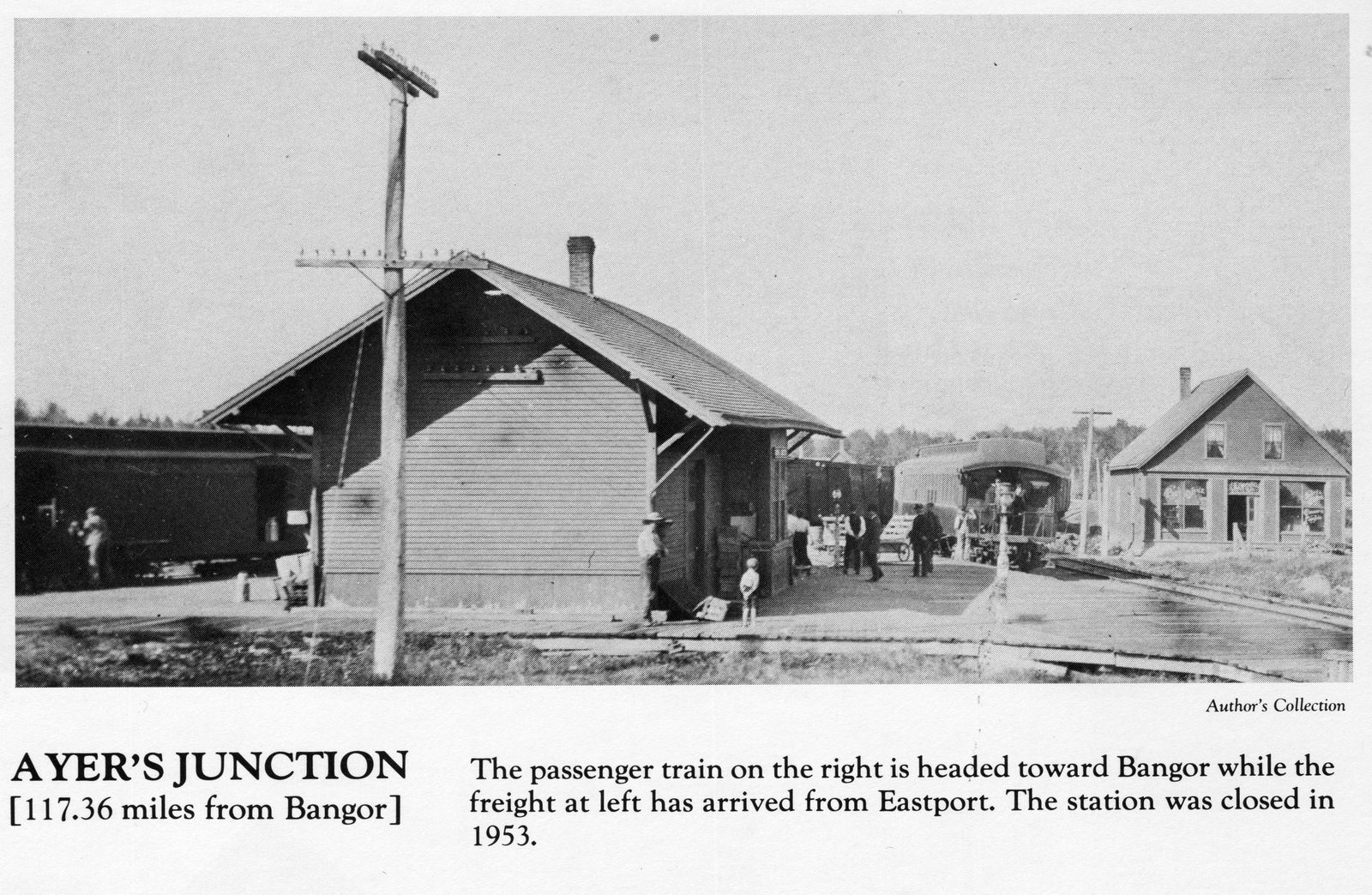

Even small towns along the route were impacted by the influx of Italian laborers. Some interesting history of the time comes from Charlotte’s historical newsletter, The Loon. The important Ayers Junction station was constructed near the Charlotte-Pembroke line. We quote at length from The Loon:

“The first sod was overturned at 1:00 p.m. on October 1, 1895 by John K. Ames and G. A. Curran. Crews began work near Machias and Columbia Falls, and were forced to stop around mid-December. Everything looked rosy. No major obstacles had been encountered. An additional $25,000 in bonds was awarded by bid in February of 1896, and many Italian immigrants began arriving in May from New York City, hoping to get work.

“Work began almost instantly. Horses and feed were shipped to Calais from Houlton via the Canadian Pacific Railway. Almost everyone immediately granted rights-of-way across their property, but a few sought monetary damages. One hundred Italian workers arrived from New York City and set up camp in Charlotte, creating a small village virtually overnight. Soon, the shantytown grew to house two hundred men and a large stable under contractor Joseph Orlando. A large outdoor brick oven was erected near Arthur McGlauflin’s house to supply these workers with the daily bread they so badly needed. One barrel of flour each day was required simply to make bread. Many commented that the Italians built the railroad living on beer, bread, and rabbits.

“The railroad had a profound impact upon the lives of everybody, but especially upon the lives of the common citizen. Now they could go places they never dreamed of for a fraction of the cost of taking a stagecoach and with much less wear and tear on themselves if they rode their own horse. Many had mixed feelings about it. For example, when Gladys Bridges was quite young, her father would take her on Sunday buggy rides. One Sunday he told her of a railroad that would be built in town and about the trains that would run on it. This was about late 1897, as they had begun to cut the right of way. He showed her the right of way as they were going to visit their old homestead, and she wondered how they were going to get there without getting hit by one of those trains. Later, when Italian immigrants arrived, they had another camp on the road where Russell Annis lives, with another one of those brick/stone ovens. Once, Gladys remembered when one of the Italians came to her house. Her mother was trying to find out what he wanted and they were both scared half to death when they thought he wanted their ax. They finally found out he wanted to buy eggs when he pointed to the hens running around in the yard.

“The three articles that appear in the Reminisces column should do justice to an adequate sense of what the railroad meant to Charlotte. Several townspeople worked on the railroad, either helping in its construction, or working on the finished product. Wellington J. James kept a journal as he worked building the railroad during November, December, and January of 1897-1898. According to his notes, they paid $2.75 per day for a man and a team of horses, and $1.95 per day for a man and one horse and cart. Several people drove horses for him, including John Apt, Thomas James, Frank McGlauflin, and a ‘Lincoln.’ He boarded Italians that came by his house looking for a place to stay, and he made a note of ‘Working for Wheetman,’ which could possibly have been his actual name or a phonetic spelling of Wheaton, the contractor that built up from Pembroke to Eastport Junction.”

After building the railroad, almost all the Italians went to major construction projects elsewhere. Few of them stayed in the area but this was to change with the construction of the Woodland Mill.

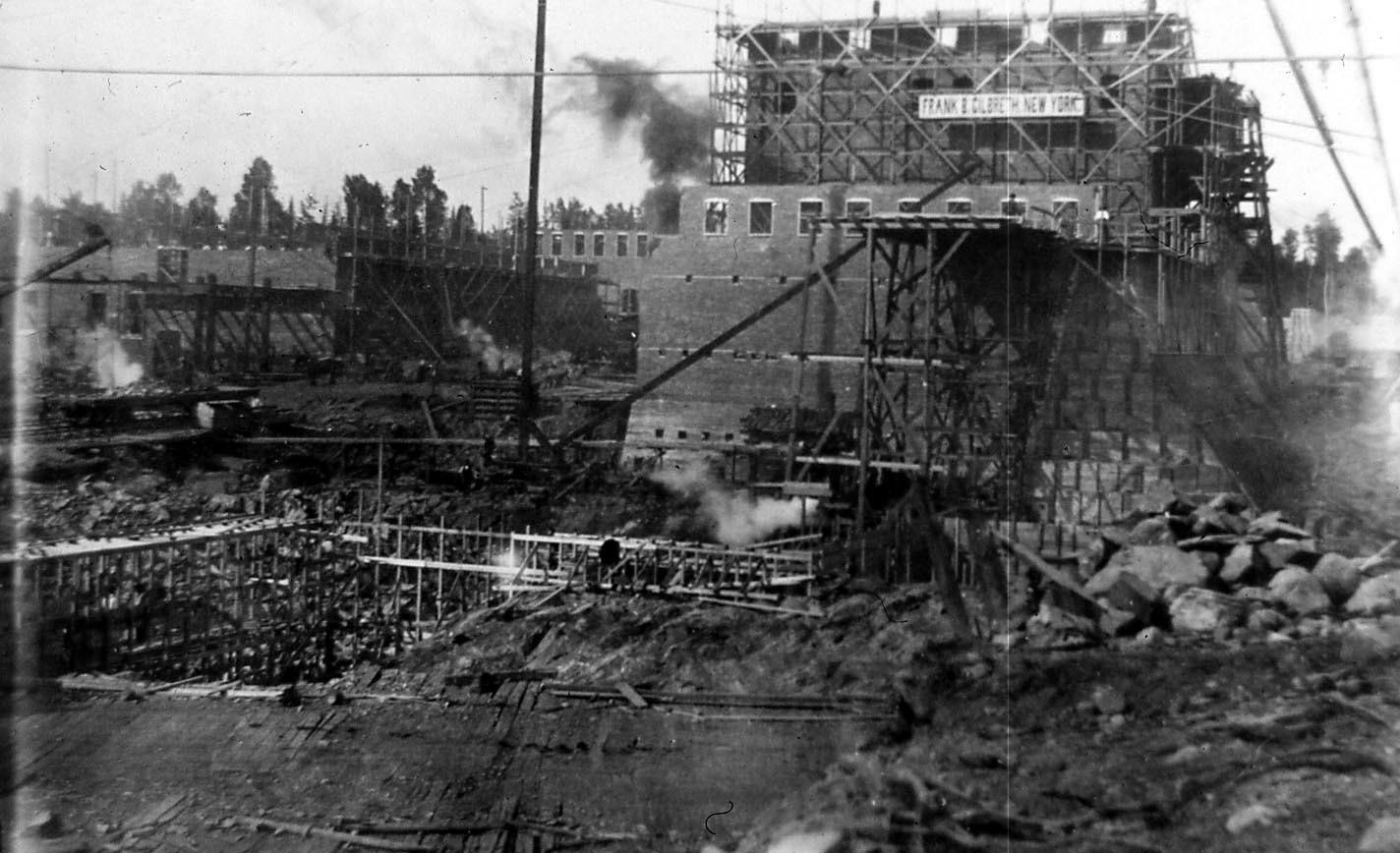

The Woodland Mill was built by about 1,000 Italian laborers in 1905-06. The photo above shows it during its construction. According to Davis’ history of the St Croix Valley the lumber industry was in decline, but:

“The newspaper and publishing industries were expanding rapidly and offered an increasingly large market for cheap paper manufactured from wood pulp, and pasteboard cartons, another wood pulp product, were beginning to replace wooden cases. Hence pulp mills made their appearance in the various eastern river valleys. The closing of certain lumber mills left good power sites available.

The industry got underway on the St. Croix in 1903 when Irving R. Todd, son of the lumberman C. F. Todd, established the Eastern Pulpwood Company and built a small pulp mill at Baring on the site of the old lumber mills. A small quantity of pulp was manufactured here, and for the next several years the firm cut and shipped thousands of cords of pulpwood by rail and by vessel. In 1904 the St. Croix Paper Company, with a capital of $2,500,000, was organized at Calais and incorporated under Maine laws. One of the moving spirits was Frank Todd of St. Stephen, another member of the lumbering family, who became president of the new concern. Much of the capital came from Boston and New York. The company took over the extensive timberland holdings of F. H. Todd and the power site at Sprague’s Falls on the American side five miles above Baring which had also belonged to him. During the next year a large dam and a pulp and paper mill were built at a cost of about $500,000. The company also put up clusters of drab little houses for workers many of whom were Italian contract laborers. Some of these poor wretches tried to flee, but usually they were caught by Charles Murray, the hard-boiled labor contractor who supplied them. By 1906 the settlement had become the town of Woodland, and the mill, with 500 men on its payroll, was turning out eighty tons of paper daily. Its best customer, The Boston Globe, took forty tons. About 30,000,000 feet of pulpwood was used annually. Some of this was supplied by the old lumber contractors, some by the lumber companies themselves, and some by the Eastern Pulpwood Company whose agents scoured the entire region.”

The photo above shows Michael Foggia and a group of his Italian countrymen who were often referred to at the time as “Sons of Sicily” enjoying a respite from their backbreaking work. While the workers were theoretically free to leave whenever they wanted, in fact they were more like indentured workers, required by a contract which they didn’t understand and which provided them no rights other than to do as “boss” ordered without complaint. Working conditions were often deplorable. The Charlie Murray mentioned above was actually an Italian immigrant himself although his father was Scottish. He presumably spoke both English and Italian and was a valuable agent for “The Man” during the construction of the mill. He did become an important and worthy citizen of the young town of Woodland and was as responsible as anyone for its civic growth during the town’s early years.

In 1913 the Grand Falls Dam was built just upriver to provide electrical power for the mill. Again Italian laborers were called upon to do the work. Some are pictured in the photo above. Local resident Robert “Bobby” Carle has some interesting recollections of his time working with the Italians who, not surprisingly, made up most of the workforce on the project. According to Joyce Carle, Bobby recalls:

“Before the dam could be built, the flow of water had to be stopped at the site. A cofferdam was built in back of the area to hold back the water and a canal was dug around the site re-routing the water. This digging and all similar work was done by hand with a pick and shovel. Eight hundred Italians were brought over here for the manual labor. Bobby drove his team on the dump cart which was loaded by hand labor. He remembers that he wasn’t supposed to get off his wagon at all, but just sit and be loaded and then drive off and dump his load at the right place at the designated spot. There was a walking boss, whose job was to see that the men dumping the dump carts were in the right place at the right time. The Italians had their own boss, who could speak both English and Italian.

“A tragic episode happened where some dynamite had been put in along the ground to aid in the excavation. All of it blasted when it was supposed to except one stick which was not recovered. Later when one of the Italian laborers was taking a swing at the ground with his pickax, he hit the dynamite, which exploded blowing him into the air over the little push cart he had been loading. The man survived but was in the hospital for a very long time.

“The company built camps for the Italian laborers and they had their own cook and food. Bobby remembers that even back then, they ate a lot of spaghetti. One story he remembers is about an Italian who saw an owl one night and killed it, thinking it was like a chicken, He made a stew out of it and it made him sick. Next day when he didn’t show up for work, the boss asked where he was. His friend replied ‘Too much big-eyed chick.’”

(This anecdote is confirmed by Dr. Barker, Woodland’s first doctor, who writes: “An amusing item: One day, an undersized Italian came to see me, in severe pain [colic] saying: ‘Poor Tony, me seek at de bel, seek at de gut, me meet ‘big eye chick.’ On further inquiry I found that someone had given him a dead owl, which he had cooked and eaten.”)

“In the evening the Italian laborers had a big outdoor bonfire where they cooked their meal. After they ate sometimes they sang, and played guitars, fiddles and mouth organs. Bobby remembers that they made beautiful music even though he couldn’t understand the words. They drank something that was known as ‘Italian Beer’ which would knock for a loop any native that tried it, but didn’t seem to have any effect at all on the Italians. He also remembers these people as being very hard-working, pleasant and agreeable.

“When spring and the classic Maine ‘mud time’ came, it became very difficult to work on the dam. During the day the horses’ legs became caked with mud which by night-time hardened like cement. Those drivers who were really concerned about their horses’ welfare took them down to the river each night and washed the horse’s legs thoroughly. If this nightly ritual was neglected, then all of the hair came off the horses’ legs… Bobby remembers that many of the Cone horses were in this condition because they had hired drivers to look after them and because the horses didn’t belong to them, didn’t bother. So we see that even in those days there were the types that only put their time in, and felt no sense of responsibility toward other people’s property.

“Conditions worsened and it became difficult to find enough to keep a team working all day. Bobby then decided that he had had enough and moved back home: quitting before the dam was quite done. About this time the Ward Company that he had worked for all this time, failed and the work was halted for a week or so. Bobby doesn’t know what caused them to fail; the Italian laborers had struck for more pay a while before that, so that may have been a contributing factor. At that time everyone, laborers Included, got a fifty-cent a day raise.”

As Bobby Carle states above, conditions were not good for horses and men alike, and the Italians were justifiably unhappy. The owners were less than unsympathetic and employed heavies to maintain discipline. Ned Lamb notes in his history of the dam about an Irishman enforcer named John McCormack who also figures in other account of the project:

“The Italians took lumber to build their shacks, the bootleggers came around too often; small tools disappeared and the big boiler fittings often turned up missing; so a hurry up call to Woodland brought up a constable and night watch in the person of a large and heavy-footed man—John MacCormick, who gained fame in fight circles for staying one half round with a boxer known as the Russian Bear. John allowed the Bear hit him when he wasn’t looking, and he wanted nothing more to do with such irrational men—hence his retirement from the squared circle. The next night after taking over he caught a small but virulent type of individual making off with a bunch of shingles. Collaring the culprit John brought him up to the office and handcuffed him to a tree. ‘There,’ said Jack, ‘I’ll know where you are tonight!’ Slipping through the shadows came another son of Sicily armed with a huge and very sharp axe. A couple of lusty swipes and down came the tree, while John inhaled a cool beer in Augustine’s emporium down near the track. The two Italians then legged it for the blacksmith shop and what they did to the cop’s darbies is nobody’s business.”

In the end, the “Sons of Sicily” gave much more than they took from the St Croix Valley and many stayed to become good citizens of their communities. In the 1890 Calais Directory there is a single Italian family listed. By the 1930s Calais had many Italian families, Bernardini, Checchi, D’Archangelo, Parento, Tori, Dicenzo, Cassalino; and several families had successful businesses.

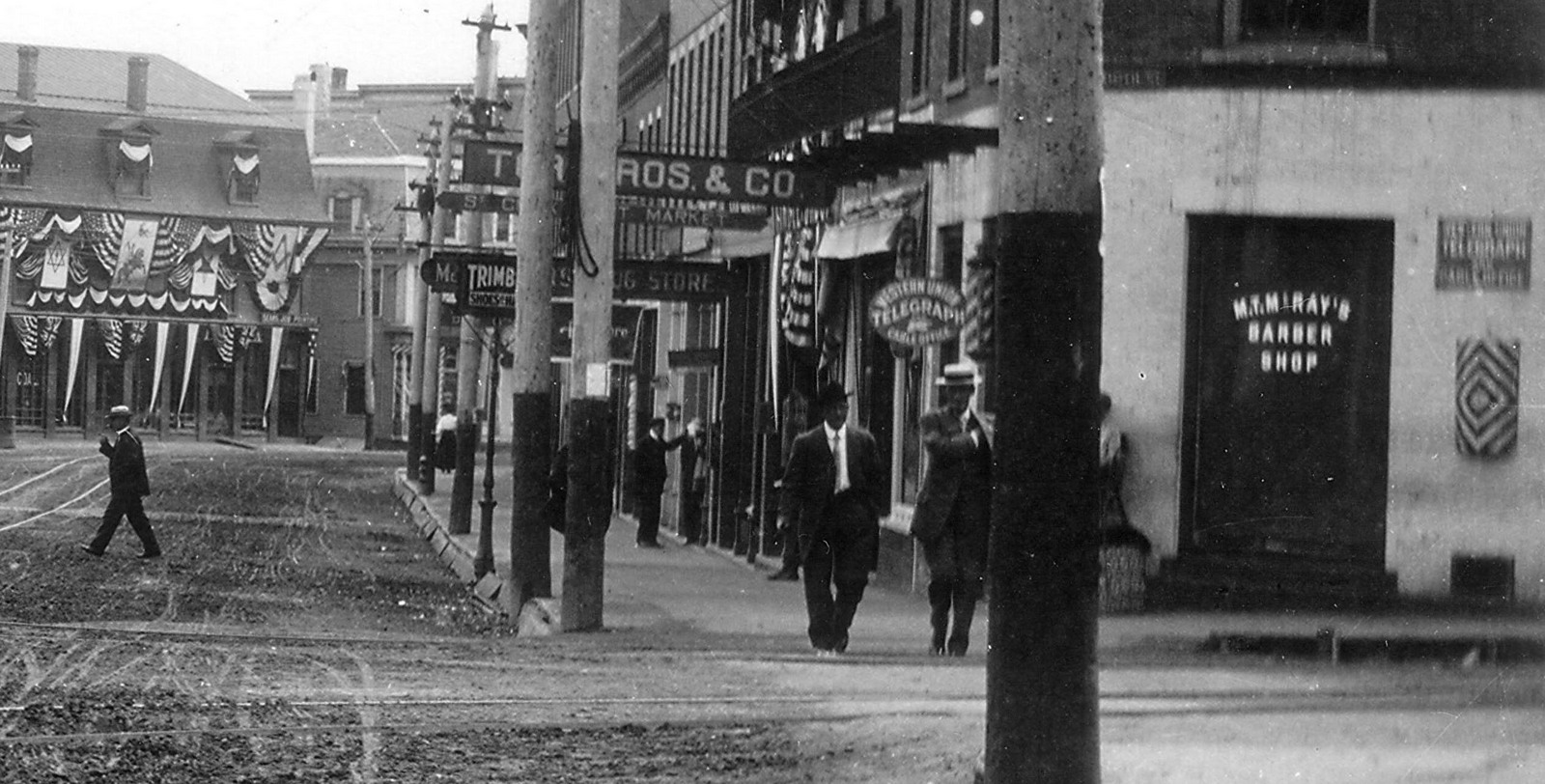

Tori Bros. & Co. had a fruit and a general store, both situated at the corner of North Street and Main (in the above photo), and later in the Syndicate Block near Calais Avenue.

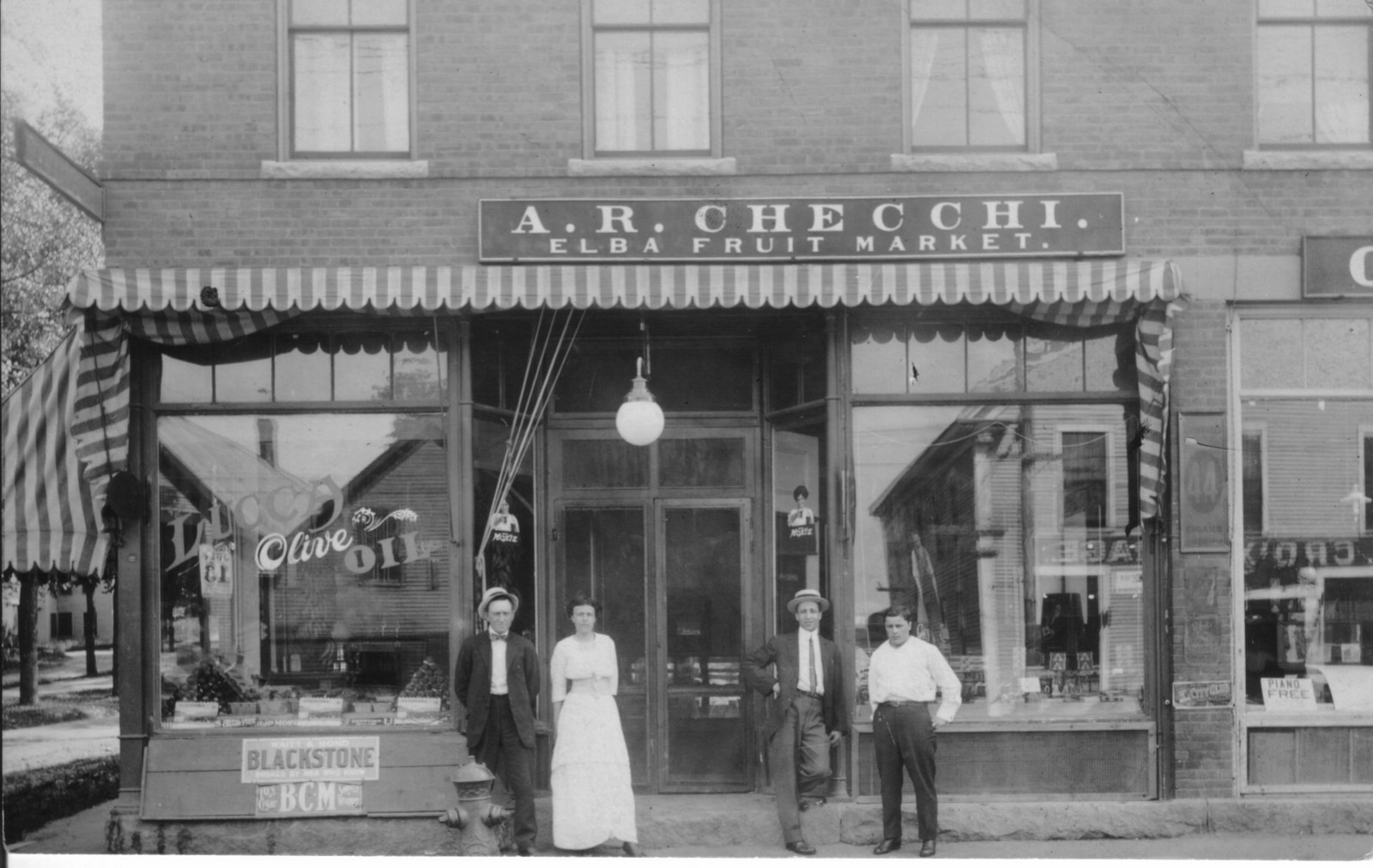

The Checchi family operated a fruit market and grocery at the corner of Main and Calais Avenue for decades. It was later owned by the Pisani family.

The Bernardini family started out in Calais with a fruit market on Main Street below Monroe Street. Like many hardworking immigrant families they saved and invested in their communities. In the case of the Bernardinis they acquired the entire block, eventually owning the Boston Shoe Store which they moved to the corner of Monroe.