John Judson Ames

As we have often noted, the St. Croix Valley sent many interesting and accomplished men and women to the far reaches of the new nation in the mid 1800s. Many went in search of gold in California and stayed as early settlers of what are now important cities. Francis Pettigrove who grew up on Hinckley Hill was a founder of Portland, Oregon. Samuel Rideout of Calais established California’s first bank, now the Bank of America and John Judson Ames, pictured above, was the publisher of California’s second newspaper, the San Diego Herald. He missed being the publisher of the first newspaper in California by a matter of a few days. He is also one of the more interesting of the St. Croix Valley’s exports to the west coast.

Born in Calais in 1821, Ames was a huge man especially by the standards of the day. Six feet six inches tall and weighing over 250 pounds, he was a formidable figure, and he was not timid about using his physical advantage to settle disputes. His father was a ship owner and captain but strangely Judson’s first enterprise as a young man, according to local historian Ned Lamb, was as the seller of “Pizen Things” in a store in the old wooden block, which is now home to Karen’s Diner and in days past the Schooner. The great fire of 1870 burned all these buildings.

Ames Shop would have been in this section of town

“In the building in which the Calais Advertiser was so long published, J. Judson Ames, a six-foot six specimen of a New England boy, kept shop and advertised that he sold “Pizen Things.” He sold pies, cakes, etc. Ames, son of Capt. J. Ames, who lived on the corner of Main and Germain Streets, was an odd genius. He made his counters to suit his tall stature and not for the accommodation of his customers. The counters had to be cut down about six inches by the next occupant of the store. Ames was among the earliest who went to California and the next heard from “Jud” Ames was that he was President of the “Handcart Society” of San Francisco. “Jud, in Calais, was noted for his patriotic airs and his elevation to the Presidency I speak of, was appreciated by the Calais community. Soon after, however, intelligence reached town that “Jud” was appointed a Judge in San Diego, where he had established a newspaper. It was on this paper that the celebrated humorist “John Phoenix” gave his humorous writings to the world. John Phoenix was a Lieutenant in the regular army and was stationed at San Diego where he and Ames became great friends.”

Before all these adventures, however, Ames married in 1844 a young lady from Lubec named Emily Walsh. Emily had just completed training at the Gorham’s Teachers’ Seminary. They had two children, George Gordon Ames and Patia McLean Ames. George died when he was only two. We have this entry from the diary of the gravedigger who buried the lad in the Calais Cemetery:

(1844) Sept 11 We dug a grave and buryed a child for Mr. John Ames at point mills. Sept 12 I went up to Milltown to collect some depts. PM We had Mr. Wadsworth hors and halld 2 small jags of meddow hay.

Ames eventually deserted Emily in Boston in 1848 and she and Patia returned to Lubec to live with her relatives. Her father, it seems, was not enamored of Judson Ames or her choice of men generally for his will bequeathed Emily his entire estate “so long as she was unmarried” when he died. It may well have been she who deserted Ames and not without cause. His father had apparently persuaded Ames that life at sea offered better prospects than selling “pizen things”. This was not to be the case.

From a San Diego history which first credits Ames with publishing San Diego’s first newspaper and then goes on to describe Ames short career as a seaman:

The editor and proprietor of this paper was John Judson Ames. He was born in Calais, Maine, May 18, 1821, and was therefore a few days past his thirtieth birthday when he settled in San Diego. He was a tall, stout, broad-shouldered man, six feet six and one-half inches high, proportionately built, and of great physical strength. His father was a shipbuilder and owner. Early in the 40’s young Ames’s father sent him as second mate of one of his ships on a voyage to Liverpool. Upon his return, while the vessel was being moored to the wharf at Boston, a gang of rough sailor boarding-house runners rushed on board to get the crew away. Ames remonstrated with them, saying if they would wait until the ship was made fast and cleaned up, the men might go where they pleased. The runners were insolent, however, a quarrel ensued, and one of the intruders finally struck him a blow on the chest. Ames retaliated with what he meant for a light blow, merely straightening out his arm, but, to his horror, his adversary fell dead at his feet. He was immediately arrested, tried for manslaughter, convicted, and sentenced to a long term in the Leverett Street Jail. The roughs had sworn hard against him, but President John Tyler understood the true facts in the case, and at once pardoned him. After this, he was sent to school to complete his education. A few years later, being of a literary turn, he engaged in newspaper work, and in 1848 went to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and started a paper which he called the Dime Catcher, devoted to the cause of the Whig party, in general, and of General Zachary Taylor’s candidacy for the presidency, in particular.

Indeed, we next find Ames in Baton Rouge, Louisiana as the publisher and chief writer under the pen name Dimecatcher of the local paper. The Daily Delta of New Orleans reported in March of 1849 that J. Judson Ames and other Baton Rouge notables were organizing a reception for ex-President Polk. He was popular in Baton Rouge and apparently wrote under several pen names including “Telegraph Man”. When he visited the city years later the local newspaper, after discussing the new telegraph line to Vicksburg, wrote:

“While on the subject of the telegraphs, I may say that I last night learned in the office that “Telegraph man” alias “Boston” alias the “Dime Catcher”, more properly J. Judson Ames, the chere amie of our Dear Delta is in Baton Rouge again, if so, extend to him per proxy the hand of fellowship and esteem.

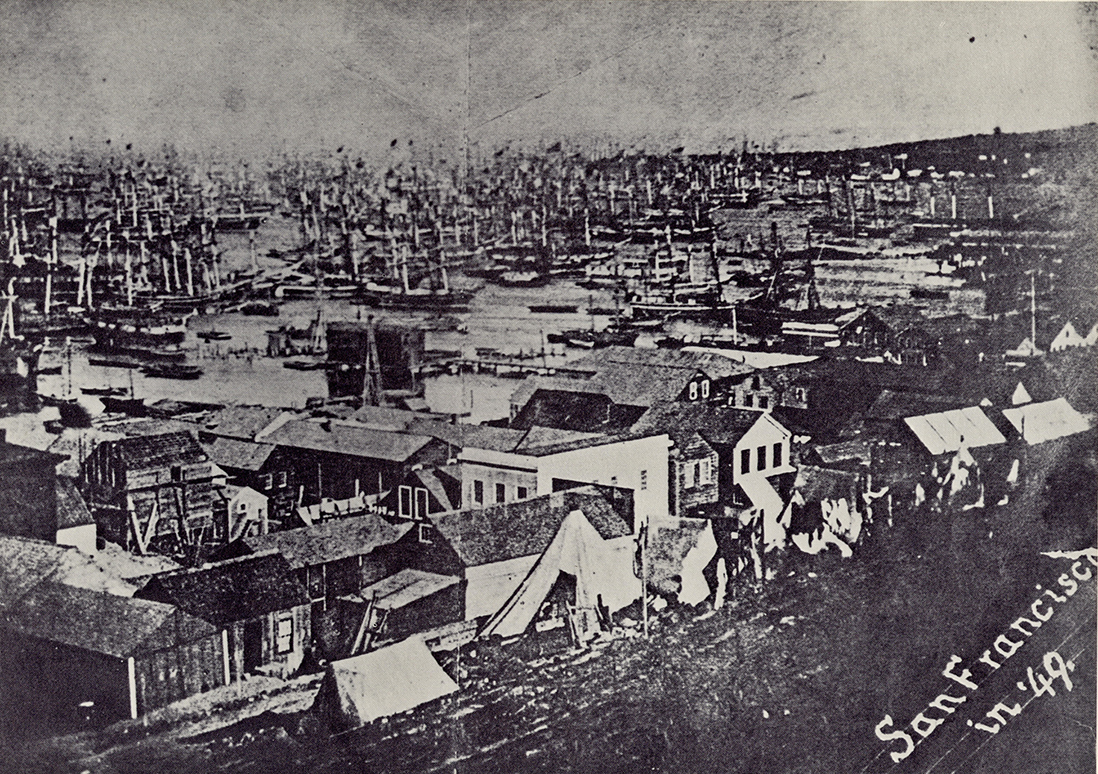

San Francisco 1849: The forest of ships in the harbor are mostly abandoned-the crews are in the goldfields

Whatever the attractions of Baton Rouge may have been, the wanderlust soon struck and some credible sources say Ames went briefly to Hawaii but very soon thereafter gold was struck in California and he was back on the west coast in San Francisco. The history of San Diego recounts:

After the discovery of gold, he joined the stream of immigrants and came to California via Panama, arriving at San Francisco October 28, 1849, without a penny in his pockets. Borrowing a handcart, he engaged in the business of hauling trunks and luggage. He always kept as a pocket-piece the first quarter of a dollar he earned in this way. His financial condition soon improved, and he formed a number of valuable friendships, especially among his Masonic brethren at San Francisco. He was present at the first meeting of any Masonic lodge in California, that of California Lodge (now No. 1); on November 17, 1849. On the following 9th of December, he became a member of this lodge, presenting his demit from St. Croix Lodge No. 40, F. & A. M. of Maine. He also became interested in newspaper work, writing under the pen name of “Boston.”

He was very successful in the “carting” business and became interested in politics where he was a patron of U.S Senator William M. Gwin who was then advocating for California statehood although with a twist. Gwin supported dividing California into the states of Northern and Southern California with the southern capital to be at San Diego, then a backwater with only a small military garrison and very few settlers. The prize in San Diego wasn’t gold but something far more valuable-the spectacular port and the very real possibility San Diego would be the terminus of the Transcontinental railroad. Even northern interests in cities like San Francisco were hedging their bets. Gwin and Ames also expected the State of Southern California to include the Sandwich Island (Hawaii) even though the Sandwich Islands still belonged to the native Hawaiians. It was assumed that the United States would soon annex the islands and there were several attempts to do so but these were only successful in 1898.

Ames was dispatched by his political friends to San Diego to publish a newspaper to be named the San Diego Herald which, the backers hoped, would generate enthusiasm in the settler community to make San Diego their home and bolster the political argument for San Diego becoming the capital of the State of Southern California.

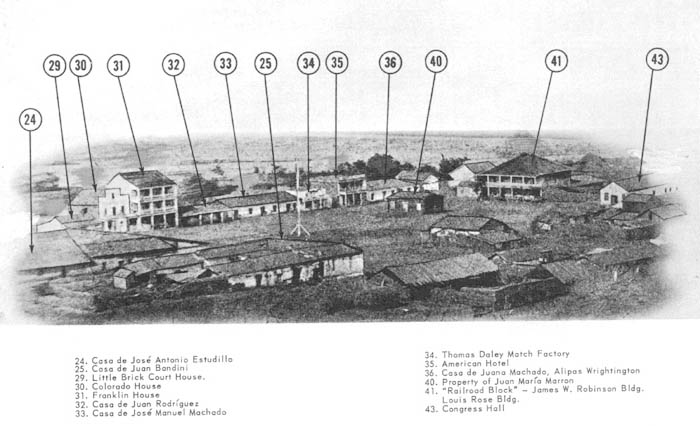

San Diego in 1860. Ames press was in the Rose Building number 41.

There isn’t much question that the San Diego Herald was bought and paid for by San Francisco political interests. The ads in the paper were almost entirely San Francisco concerns who could expect little or no trade from the scattering of San Diego settlers. To begin producing the paper Ames had first to return to Louisiana to get his printing press, but it was no easy matter to get the press back to California.

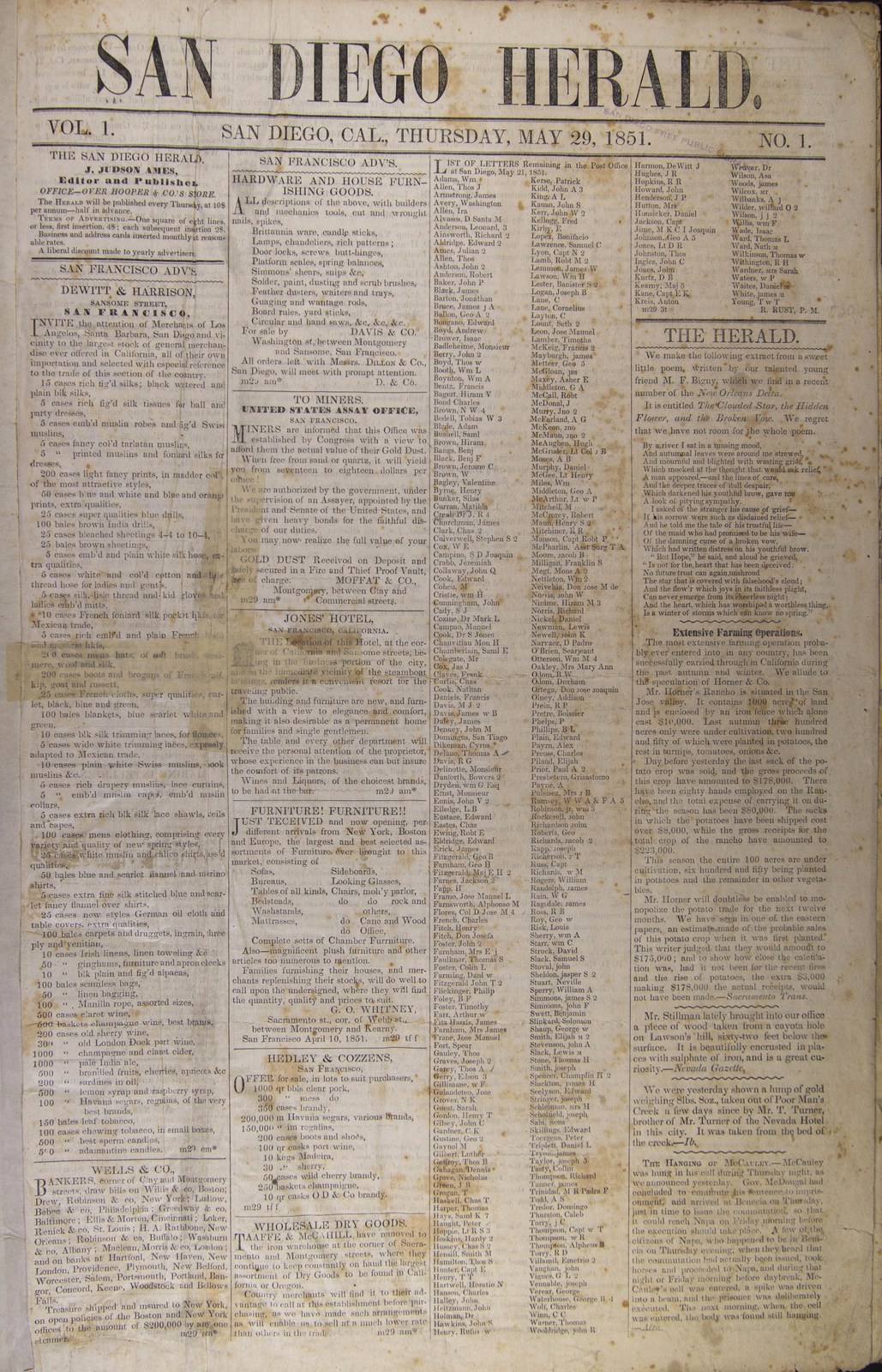

He describes his trials and tribulations in the first edition of the San Diego Herald, dated May 29, 1851.

“We issued our prospectus in December last and supposed at the time that we had secured the material for our paper; but when we came to put our hand on it, it wasn’t there! Determined to lose no time, we took the first boat for New Orleans, where we selected our office, and had returned as far as the Isthmus, when Dame Misfortune gave us another kick, snagged our boat, and sunk everything in the Chagres River. After fishing for a day or two we got enough to get out a paper, and pushed on for Gorgora, letting the balance go to Davy Jones’ Locker. Then comes the tug of war, in getting our press and heavy boxes of type across the Isthmus. Three weeks of anxiety and toil prostrated us with the Panama fever by which we missed our passage in the regular mail steamer-the only boat that touched at San Diego-thereby obliging us to go on board a propeller bound for San Francisco. This boat sprung a leak off the Gulf of Tehauntepec-came near sinking-run on a sandbank-and finally got into Acapulco where she was detained a week in repairing. We at last arrived in San Francisco, just in time to lose more of our material by the late fire.”

While in Panama he set up his press and published a newspaper titled the Panama Herald, half in English and half in Spanish. It may well have been Panama’s first newspaper.

The San Diego Herald was reasonably successful given the circumstances and Ames was an excellent writer. He pushed the party line very hard and didn’t care much what his adversaries thought of him or his paper. A number of San Diegans once wrote a scathing letter criticizing the paper to which Ames responded, “I don’t give a damn whether you like it or not.” According to an Oakland paper he was challenged to a duel by one George Davis because “Ames had printed something in his paper which could be atoned for only by bloodshed.” The duel either didn’t take place or Ames walked away unharmed.

Ames had a habit of leaving to spend weeks in San Francisco socializing with the pols and his drinking buddies of whom he had many. One paper described Ames’s absences as “going to San Francisco or elsewhere on a carousel.” During one of his long sojourns to San Francisco he entrusted the Herald to Lt. George Horatio Derby, then an officer with the small military detachment in San Diego. Ames went to San Francisco to celebrate what all thought was to be a resounding Democratic victory in the election of 1853. Under Derby the Herald no longer published flattering articles about San Diego and its inhabitants but instead Derby, who wrote under the name John Phoenix, changed the tone of the paper by often panning both the people and climate of San Diego. This was of course contrary to the paper’s purpose which was to paint San Diego as an undiscovered paradise. However, it was done in such a clever and humorous manner that Derby became somewhat of a celebrity. The final straw, however, was Derby’s change of political affiliation of the paper just before the election from Democratic to Whig. This forced Ames to return quickly to San Diego and regain control of the paper. Still, he remained friends with Derby.

In 1856 Ames traveled back east to visit friends and may have even returned home to Calais. We do know he married Elizabeth Sexton in Vermont during this trip. The Baton Rouge Gazette published a short article about Ames trip referring to him as “Boston”, one of his many pen names. Ironically, the paper wrote “Boston is said to be on a visit to the Atlantic States for the purpose of editing a work on the life and the writings of “John Phoenix” otherwise known as Lieut. Derby of the U.S Navy.” Ames has obviously forgiven Derby for the “John Phoenix” episode. While Ames was traveling in New England a stranger calling himself William X. Walton arrived on the train from the east and informed Ames’ attorney that he had been sent by Ames to run the paper. When Ames returned the new editor disappeared just ahead of Ames arrival. Ames did not know William Walton if this was his true identity.

John Judson Ames gravestone San Bernardino

In March of 1857 his second wife Eliza had died, and Ames moved the paper to San Bernardino where he married again and had a son Hudie, but he was a broken man. His political allies had been defeated, Senator Gwin had died and with him the dream of a State of Southern California with its capital in San Diego. The Transcontinental Railroad terminated at Oakland Long Wharf on San Francisco Bay and the San Bernardino paper was a failure. He was in poor health and drinking heavily. In August 1861, just after turning 40, he died. His son Hudie died less than two years later.

As to the other main characters in his life, George Horatio Derby became a nationally known humorist writing under the pen name of “John Phoenix” with his columns published in newspapers throughout the country. Sadly, he died soon after Ames. The Savannah Georgia Republican said of him a few months before he died in a private asylum in New York:

Captain Derby was better known to the country as “John Phoenix” under which signature, when in California, years ago he electrified the reading public by rare specimens of genuine wit and humor, and a sarcasm which was as gentle as it was keen and just. For a year or more we have had a continual stream of bright things from his pen, and few persons achieved a higher place, in this particular line of literature and thought, then “John Phoenix”.

Patia, his only surviving child by his first wife Emily Balch, died in Peabody Massachusetts in 1865. Emily outlived the rest of the family by many decades-dying in Weaverville California in December 1892.

Thus ends the story of John Judson Ames. Ames may not have founded cities or banks, but he was one of many St. Croix Valley natives who went west and against great odds made a difference in what was then a very rugged and wild country. When he wrote that he “had to overcome obstacles which would have disheartened any but a ‘live Yankee’” Ames was not exaggerating in the least.

Only one burning question remains. What in the world were “pizen things” which according to Ned Lamb was how he described his stock in the store on Main Street in Calais? Our search on the internet provides no answer but my wife may well have the answer-pies and things.