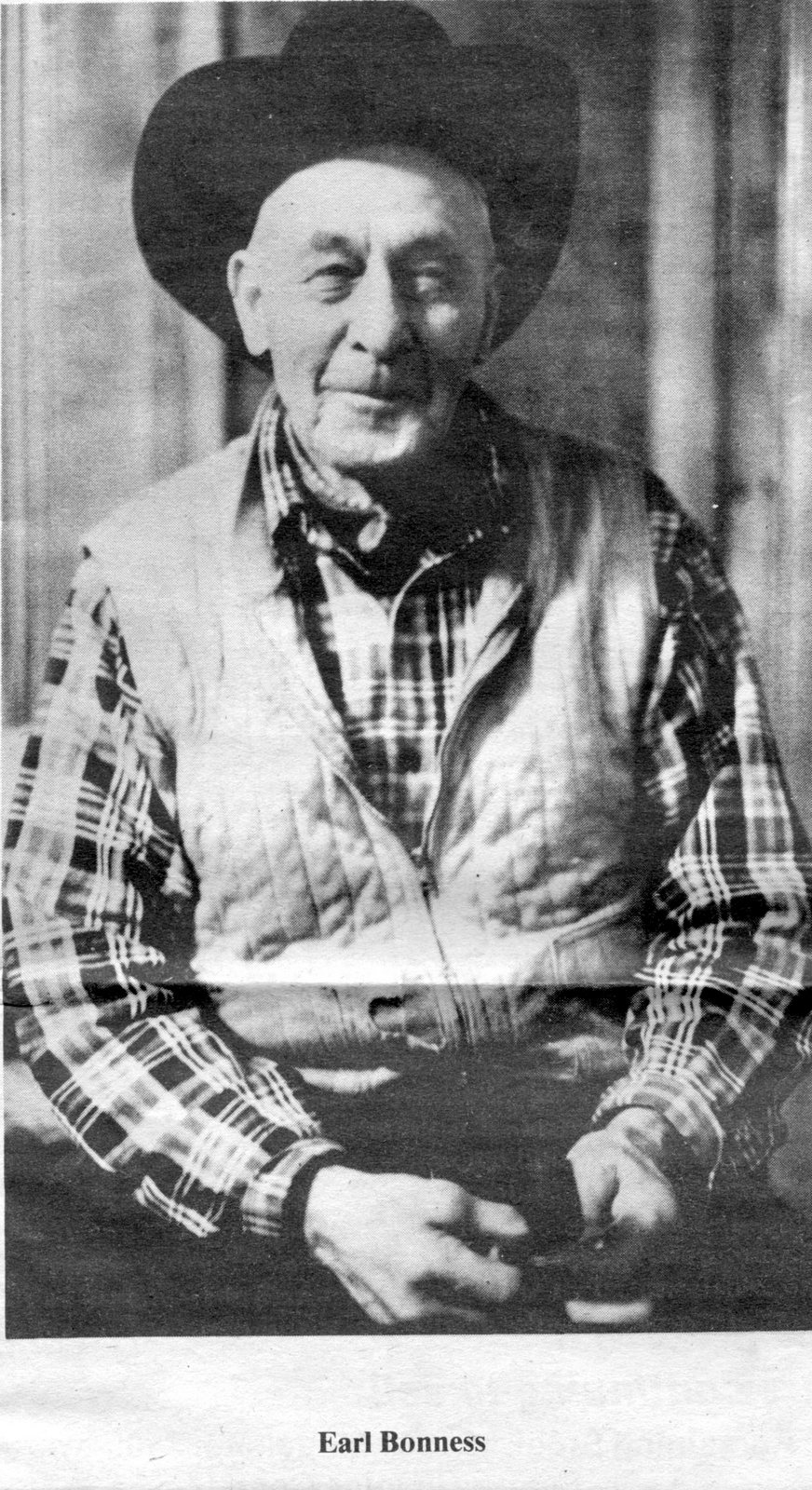

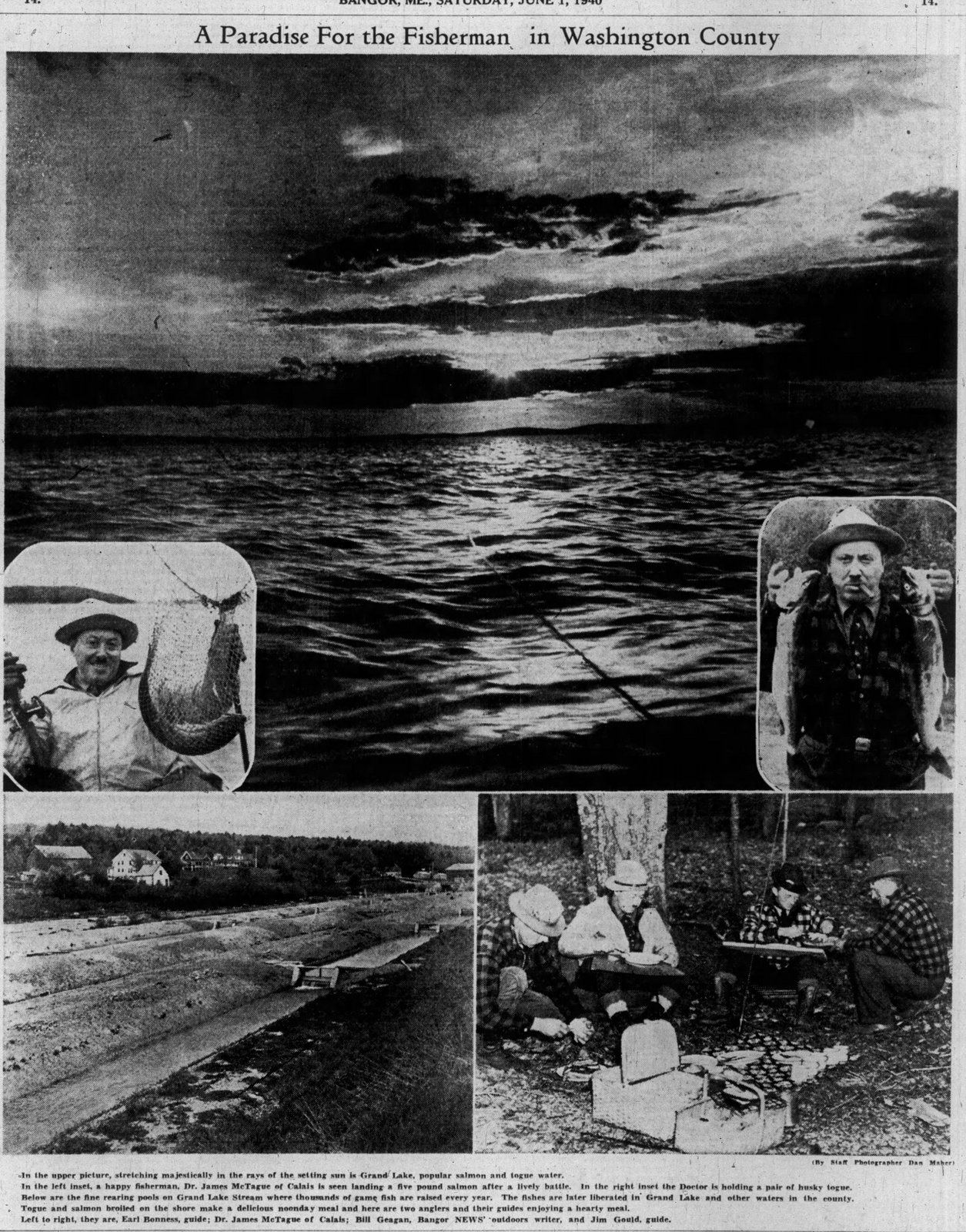

We found a copy of a 1982 article in The Calais Advertiser recently about Earl Bonness, one of Grand Lake Stream’s the legendary guides and thought it might be of interest to the group. The photos, other than the one above, were not in the article but are from the Historical Society collection.

By Patti Lanigan – The Calais Advertiser, January 7, 1982:

A short distance below the dam on the bank of clear Grand Lake Stream waters, lives Earl Bonness, noted for always wearing a cowboy hat and heading into the wild with his gun or fishing rod or traps in hand. He keeps himself far too busy to rest much in his easy chair, so it’s hard to believe he’s almost 77 years old.

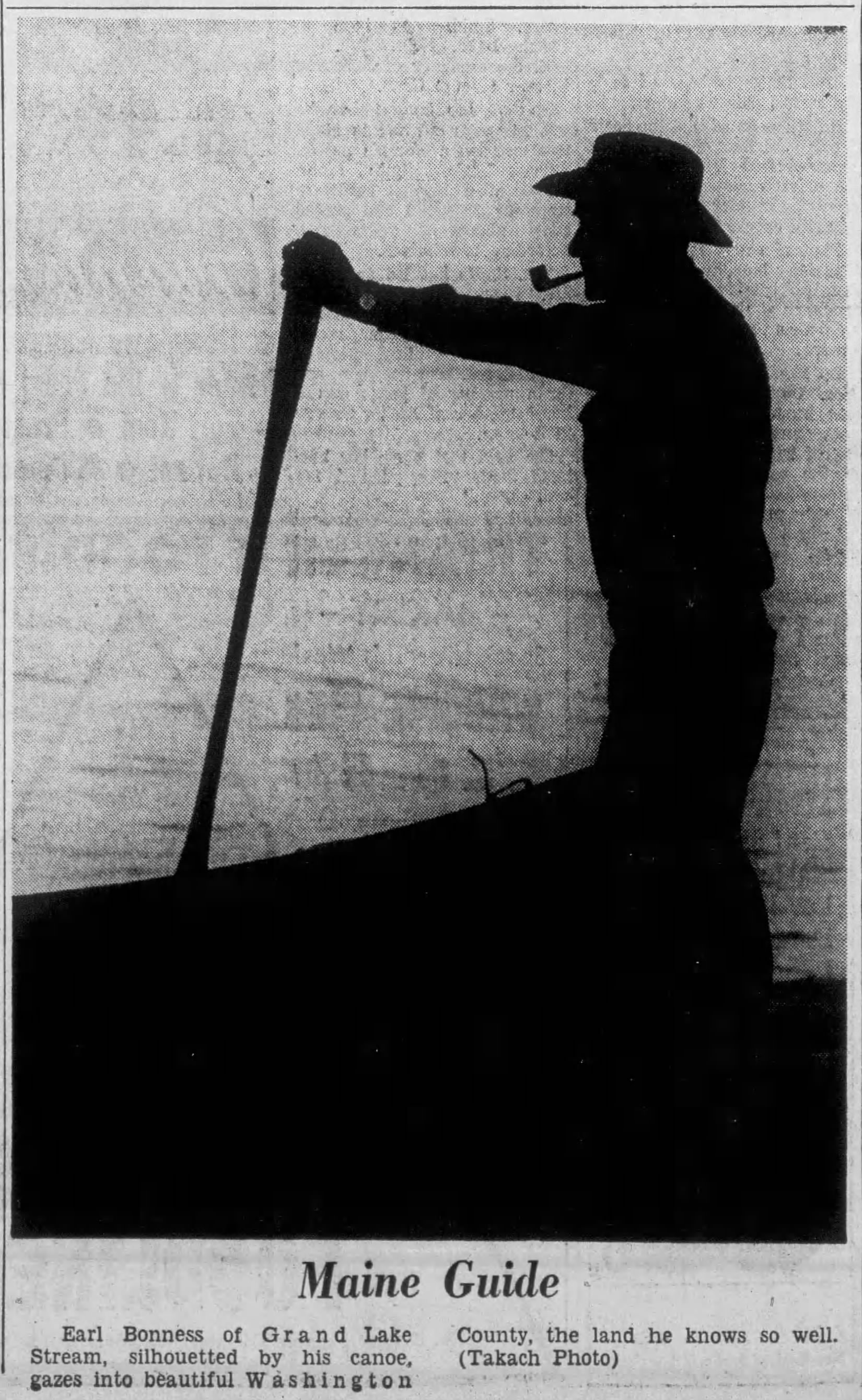

Earl Bonness in silhouette, Bangor Daily News 1970

Earl stands almost six feet tall and has a medium-sized frame that curves forward at the top. His movements are fairly slow, smooth and easy. Earl is as sturdy as a Grand Lake Canoe, and his cheeks glow with the pink of good health and outdoor living. Of Scottish descent, he once was a redhead, but now his hair is white.

Earl’s style of dress shows that he’s a sportsman ready for all sorts of activities and quick changes in Maine weather. He wears green gum rubber boots, thick socks, dark gray wool pants with a fine red stripe, an orange hunter’s vest over a heavy plaid flannel shirt, and a red bandana around his neck. The old timer chuckles, creasing the laugh lines around his gleaming blue eyes and says, “I like to be active. I’m afraid of sitting down. I may not get going again.”

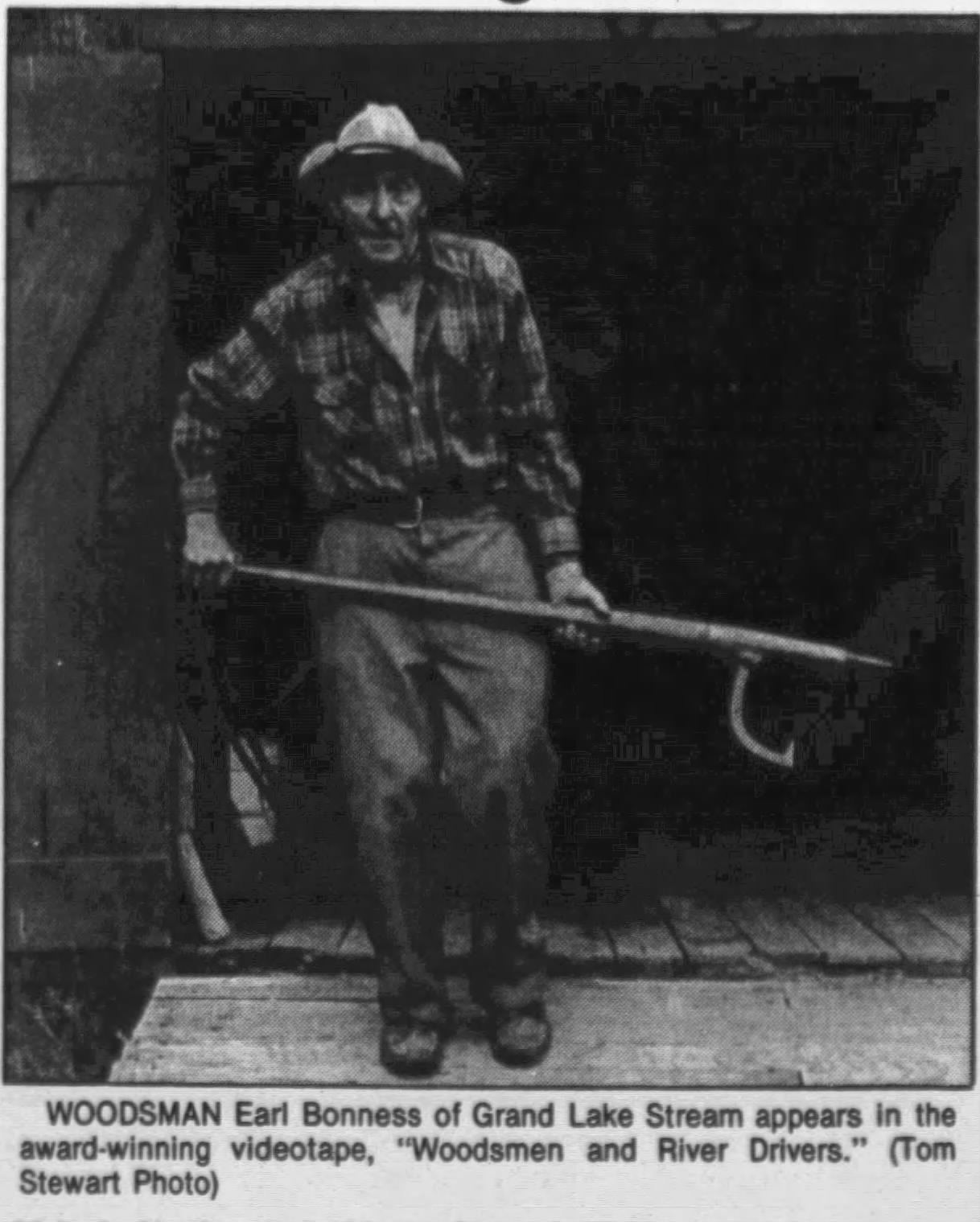

From Bangor Daily News, 1990

Earl has worked hard all of his life, mostly as a logger in the winter and a fisherman’s guide in the summer. He’s also done his share of fur trapping and woodworking. In his spare time, he fashions fine paddles of maple and white ash, small tables, and Irish three-legged stools and sells them. What he doesn’t sell winds up in his home. “Earl is always making something” says his wife Thelma, gesturing toward a stand she has used to hold pictures and a vase of dried flowers. On the grass beside their house sits a long weather-beaten bench that was made by Earl. He points to it and says, “we sit around there in the summer and tell lies.’

Storytelling is one of Earl’s strong points. He’s gotten a lot of practice in his 53 years of guiding. When the fish aren’t biting, a guide is responsible for entertaining his party. With a wit as quick and sharp as the Road Runner’s beak, a sense of humor drier than a stiff martini, and a Maine accent that puts Bert and I to shame, Earl spins tales.

“I’ll tell you an amusing little story. A lady I was guiding once asked me, ‘Earl, did you ever get chased by a bear?’ Young lady, I said, I had a long run from a bear one time. I was blueberrying and I got between a mother and her cubs. She took after me and I had the longest run ever. Got away just in time. I was running past an old pine tree, and I saw a limb about 10 feet up so I jumped. ‘Did you catch hold of it?’ she asked. Not on the way up I didn’t, but I did on the way down.” Slapping his knee and bursting into laughter he adds, “That was wicked. Golly, that was awful.”

Earl crosses his gum-rubbered feet and pauses to light his pipe. He strikes a wooden kitchen match against the bottom of the table next to his chair and puts it to his tobacco. Puffing now and then, he goes on to tell why he has always worn cowboy hats. Earl’s reason has nothing in common with the fad fashions started by the film “Urban Cowboy.” “I was out west one time and ever since then I’ve worn a big hat. Silly of me,” he said.

When Earl was about 20 years old, he left his home in Grand Falls and went to the western provinces of Canada to work as a wheat harvester. The Canadian wheat provinces were short of help, so there was an excursion train that transported workers from McAdam to Winnipeg, Manitoba. Using steam powered threshers, the men worked from early morning until stars appeared in the night sky. Their wages were unusually high for the 1920s- $7 a day.

By the time the harvesting was done, Earl had plenty of money saved to take the excursion train back home. But the night before he was supposed to leave, he got involved in a poker game and wound up broke. “I learned a good lesson,” he said, “but a sad one.” Earl was too proud to send home for money, so he took a job in a grain elevator that paid $2 a day.

In the winter he went to Butte, Montana, where he lived on a ranch and did chores for $20 a month. He remembers he had trouble at first riding the mustangs they kept. “Those little horses kicked me off for exercise in the morning. I afforded fun for the people out there,” he said, “Why, they rode like they were glued into the saddle.” Earl persisted though and became a decent horseman before he left the ranch. His grandfather had always told him, “If you tackle something, stay with it and give it a good go.”

When spring came, Earl left the west with a cowboy hat on his head full of stories and worked his way back home. One summer day he rode up the St. John River on a grain boat from Ontario. He’d been sick at sea for three days and was awfully happy to touch land in St. John. From there he went to Grand Lake where he’d met some old guides and his mother’s friends when he was a young boy.

The father of Earl’s mother had come to Grand Lake in 1868 to work in what was then the world’s largest leather tannery. He and his family drove a team of horses from Cooper to Princeton. They spent a night there and then went on a steamboat to Greenlow Landing on Big Lake, three miles from Grand Lake Stream. Their horses and wagon rode behind them on a big scow.”

Grand Lake’s tannery flourished until the 1890s, when the method of tanning changed from using hemlock bark to chemicals which were cheaper and easier to use. The Grand Lake Tannery didn’t switch to chemicals and tanning eventually died out there. New tanneries were built near industrial cities.

At the turn of the century, wealthy sportsmen began flocking to Grand Lake to fish for salmon, bass, and togue. They didn’t know the lake very well and found it difficult to paddle and fish at the same time, hence the necessity for the birth of the Maine guide. For fun and pay, a guide would paddle fishermen all over vast Grand Lake, showing them where and how to catch different fish. He’d bring wood with him, cook on the shore a hearty lunch of chicken, steak, or fish if they had any, and tell stories about life in the wilderness of Maine over a cup of unusual coffee. Earl says they beat an egg into it so the grounds would settle and leave the coffee clear and tasty.

Grand Lake Stream sports and guide about the time Earl got his guiding license

Earl got his guiding license in 1928 and joined a force of 30 regular guides who worked with the sporting camps that were owned by townspeople. He remembers guiding a lot of nice people. A few of them were famous. One such man was Karl Taylor Compton, chairman of the board that evaluated tests of the atomic bomb, an atomic physics researcher, and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Another was Admiral Gerry Land, a hearty, little man who was signed by Roosevelt in WWII as maritime commissioner. In May, shortly after the ice had gone out of Grand Lake, Land went swimming. “It made us shiver watching,” said Earl. A third remarkable man Earl guided was Robert Ingalls, a shipyard owner from Birmingham, Alabama. Ingalls successfully began welding rather than riveting together the metal plates that form the hull of a ship and helped to improve shipbuilding methods in Bath, Maine.

From a Bangor Daily article on the excellent fishing in Grand Lake Stream 1940, Earl guiding Dr. McTague of Calais

In his young days Earl was a familiar sight at dances all over Washington County. “Most people know me,” he says, ” ’cause there’s nothing else looks like me.” He doesn’t dance as much as he used to, but he still does a jig now and then and makes it to Rod and Gun Club dinners.

Earl is amazed at the changes he has seen in his lifetime, especially in air travel. He first saw an airplane shortly after WWI, and since then has seen larger planes, jets, and the Columbia space shuttle.

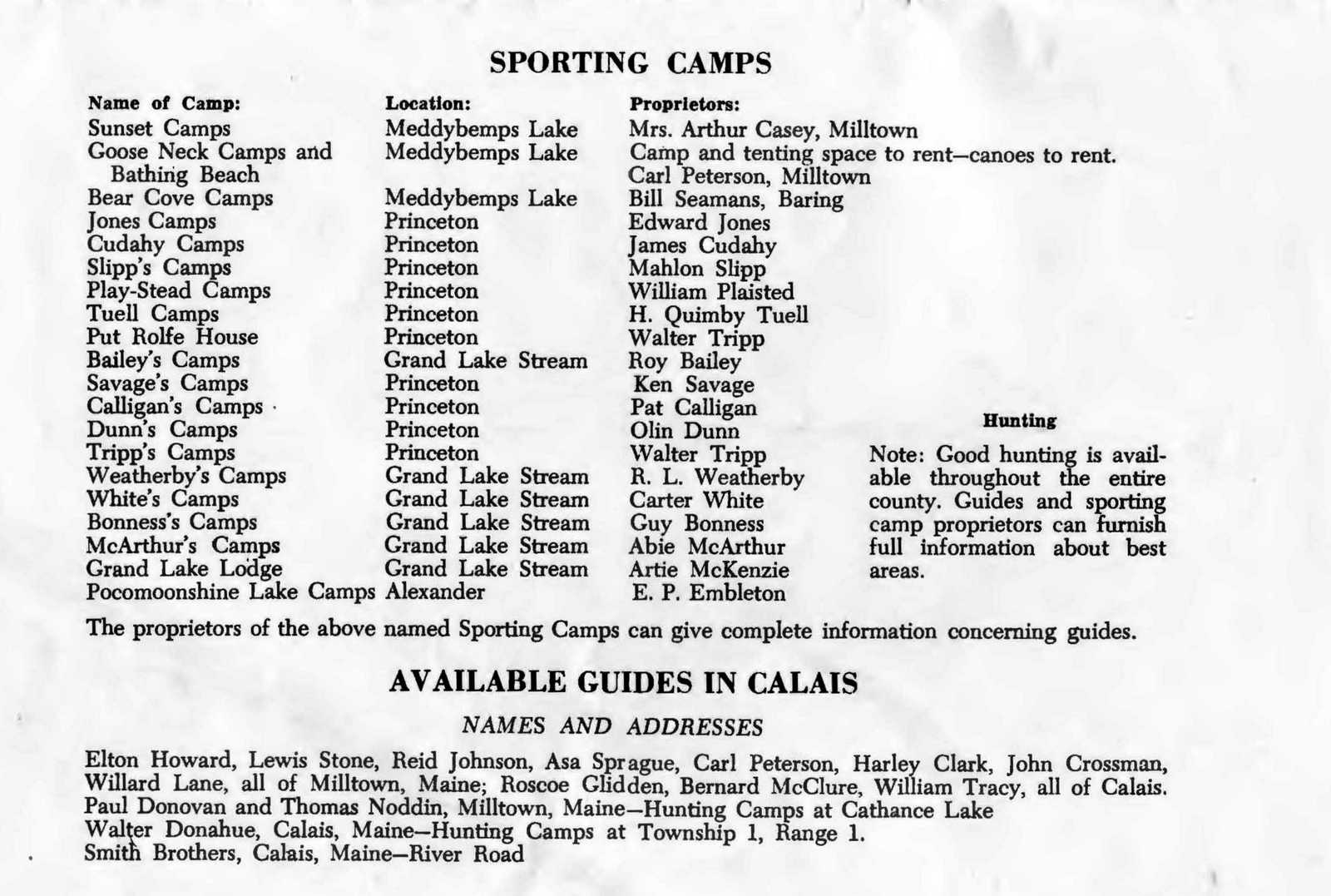

From a 1955 Calais Chamber promotional brochure. There were 15 guides in Calais in 1955 – more in Grand Lake Stream.

Guiding has undergone some changes too. When Earl started guiding everyone paddled. Now outboard motors provide much of the power. The sports who visit Grand Lake these days are not as wealthy as those who came in the old days, nor do they stay as long. According to Earl, many of them get three-day licenses and are very anxious to catch what they can in that short time. In the past sportsmen vacationed repeatedly there for a week or two at a time.

Young guides in Grand Lake Stream got a lot of work this year, and Earl guided 40 days. However, he believes the era of guiding is fading fast. Many people have big, reliable boats with powerful outboard motors. Maps that show the shape and depth of lakes and printed tips on fishing equipment and techniques are available. In short, people can take care of themselves. “In 20 more years, the old-time Maine guide as we know him will only be a memory,” says Earl. He grins and adds, “I’ve often said a guide is only a necessary evil.”

Will the oldest working guide in Grand Lake Stream be taking sportsmen out in his canoe next spring? “I wish you hadn’t asked me that,” says Earl. “I’ve been contemplating retiring, but I wouldn’t know what to do with myself.”

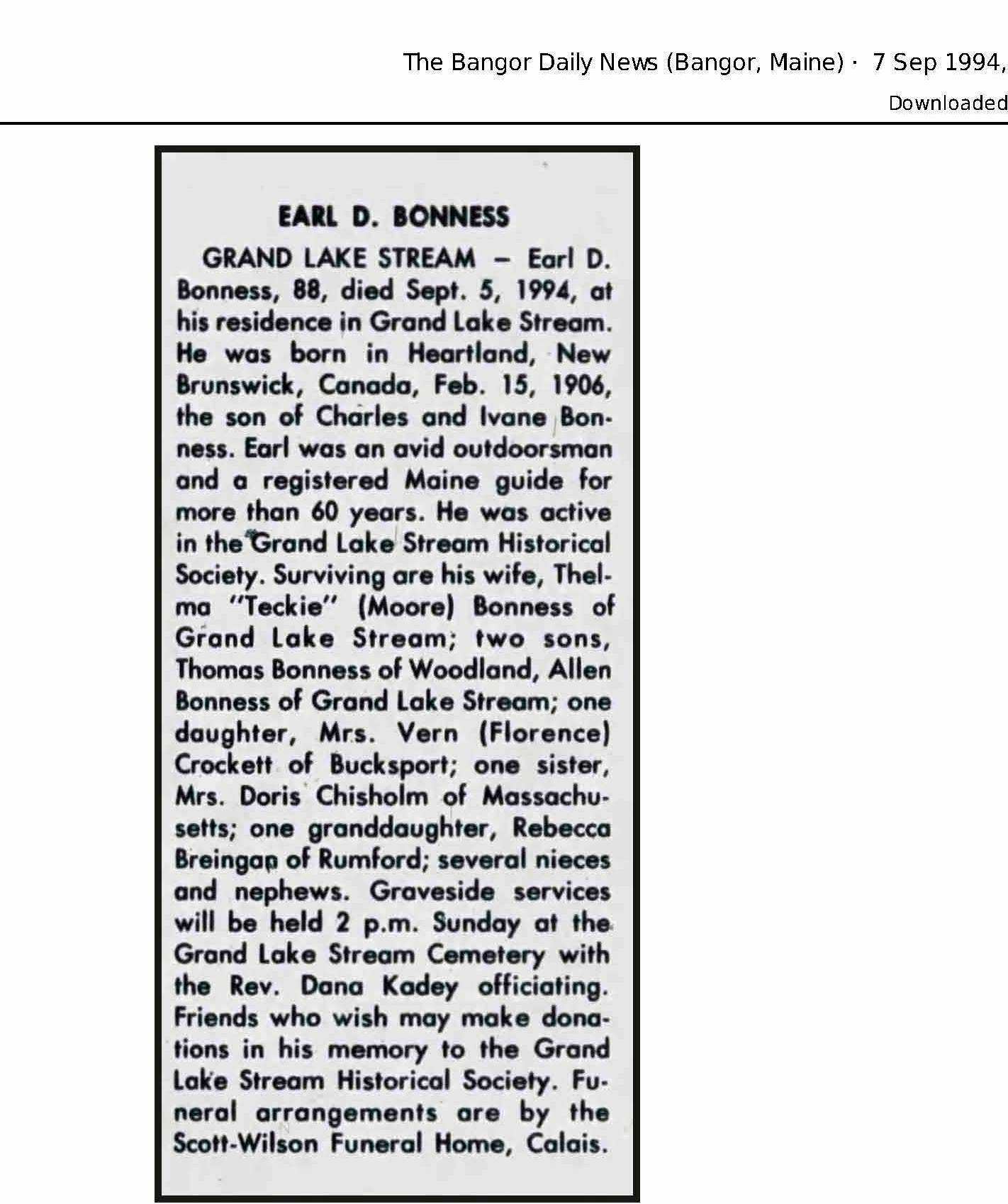

Earl Bonness died September 5, 1994.

Earl Bonness was often mentioned in Bud Leavitt’s columns in the Bangor Daily and after Earl’s death Tom Hennessey, another Bangor Daily outdoor writer, wrote:

There’s no telling how many sportsmen shared Earl Bonness’s canoe during the 60-odd years he guided at Grand Lake Stream. It’s a sure bet, though, that the days they spent with the veteran outdoorsman produced golden memories that time will never tarnish.

The way I see it, there must be a long line of Maine guides strung along the shore of the River Styx. Because, like Blaine Lambert and Earl Bonness, they’ll all have to stop and make a cast or two before crossing.