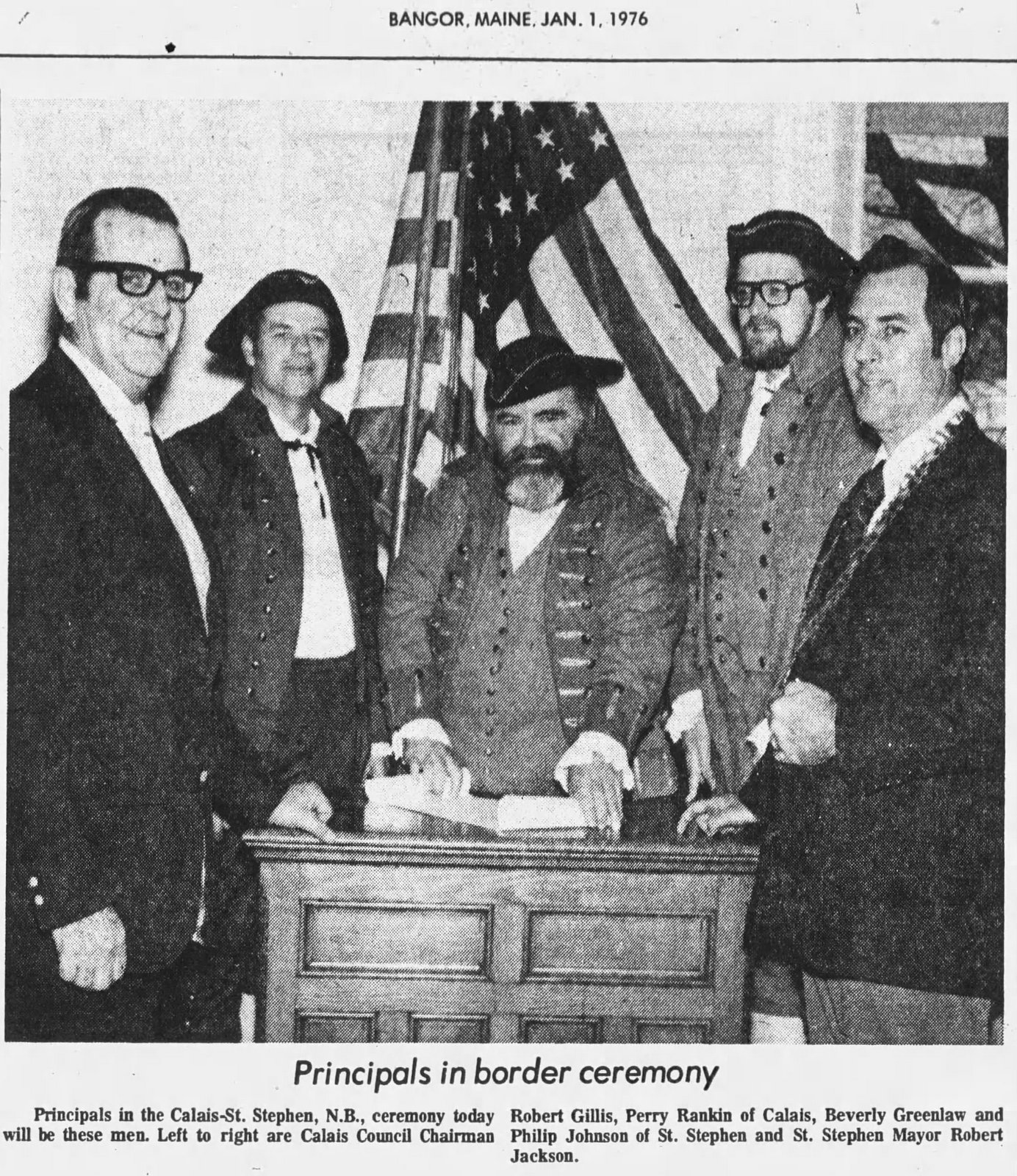

Colonel Benjamin Church(center) given role of honor in 1976 Bi-Centennial celebrations

When Calais became first in the nation to celebrate the country’s Bi-Centennial in 1976, a prominent figure in the festivities was Col. Benjamin Church, a Massachusetts native who had spent but three days in the St. Croix Valley in 1704. How Church came to play such an important role in the ceremonies is described in the accompanying Bangor Daily News article:

The first in the nation international border event will be held here at 9:00 AM New Year’s Day when Saint Stephen New Brunswick town officials extend a “hands across the border” congratulations to the United States on the opening day of its yearlong bicentennial anniversary.

Calais city officials will represent the United States at the symbolic ceremony being staged in one of America’s eastern most communities. The role of Colonel Benjamin Church, as self-appointed peacemaker who reportedly came to the Calais- St. Stephen area then known as Lincourt in 1704 will be portrayed during the Thursday morning festivities.

A representation of Colonel Church was chosen by the 1975 Calais- Stephen International Festival committee as the official symbol of the annual border event last August. Church who is believed to be a native of Salem MA became a soldier and reportedly arrived in the Calais area intent on quieting an Indian uprising in the early 1700s. Apparently to his chagrin, no uprising was in progress.

The International Festival Committee selected Col Church as a symbol for the festival

One of many Colonel Churches in Festival parades

It is indeed true that the 1975 Festival Committee had chosen Colonel Church as Marshall of the 1975 Festival Parade based on the characterization of the Colonel as an “overweight colonel tripping and stumbling his way up the banks of the St. Croix River searching for an enemy which did not exist.” Nothing could be further from the truth. While the Colonel was, in fact, rotund and out of shape he had acquired a well-deserved reputation as a relentless, brutal and cruel “Indian fighter” often called upon by the Massachusetts authorities to conduct “punitive raids” along the rivers and shores of what is now New England, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Church’s 1704 raid on the St. Croix or “punitive expedition” as it was then described was his fifth such raid up the coast since 1689 and his last. The area was then a battleground in the conflict between France and England over territory in the New World, territory rich in natural resources especially furs which were worth their weight in gold during the cold European winters.

How Colonel Church’s reputation and history escaped the notice of the International Festival Committee is troubling to say the least. Doug Dougherty, a knowledgeable and respected St. Stephen historian in the 1970s had published articles revealing that Church “came to the area to massacre Indians who he greatly disliked” and even a cursory reading of history of the expedition showed this to be his primary purpose although Church was equally intent on killing or capturing any Frenchmen he found in the St. Croix Valley.

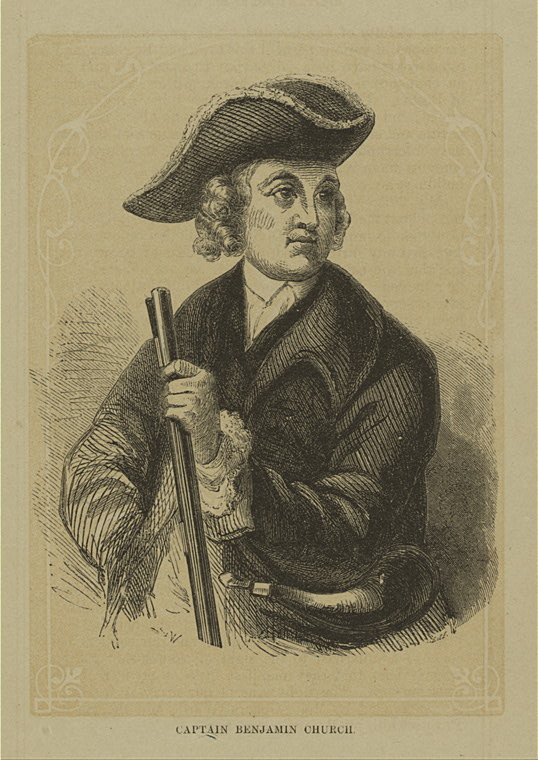

Colonel Church in his youth

Church was certainly no “peacemaker” and there was no “Indian Uprising” for Church to put down in 1704 as there were no whites in the St. Croix Valley for the Passamaquoddies to rise up against. The Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony had sent an expedition to the St Croix Valley in the 1680s to take a census and found only two whites, both French, living along the river. The French authorities conducted a census of the area in 1688 which was then named “Lincourt” and found two white men, 20 male Indians, 20 female Indians and 33 Indian children, 75 in all; 4 houses, 20 wigwams, 2 guns, 1 sword, 1 pistol, 23 acres of cultivated ground on which they grew Indian wheat (corn). These peaceful inhabitants were hardly a danger to English interests in the St. Croix Valley. In fact, it was to be half a century before the first English settlers found their way Downeast.

The true reason for the attack on the St. Croix Valley in 1704 can be found in the Deerfield Massacre of February 1704 which occurred during Queen Ann’s War. According to the eminent Canadian historian William Ganong of St. Stephen, the relative peace between the French and English and the English and the Tribes was broken in 1702 by the English.

The English likewise made an effort to gain the friendship of the Indians, and had well-nigh completed an amicable treaty with the Maliseet tribes, when the folly of a New England marauding party, which plundered and destroyed St. Castine’s post at Penobscot, brought on another crisis. The Indians were greatly encouraged to break with the English by Vaudreuil, governor general of New France.

The renewed outbreak, known in history as Queen Ann’s war, was quite unexpected. Indians and French, numbering in all about 500, divided themselves into several bands, which, in August, 1703, simultaneously fell upon the settlements of Maine. Terror and confusion reigned at Casco, Saco, Wells, and in fact along the entire frontier. About 155 English were killed or captured in the several attacks.

The militia was called out forthwith, and the legislatures of New Hampshire and Massachusetts offered a bounty of £20 for each Indian prisoner under ten years of age and £40 for every older prisoner or for his scalp.

In early 1704 the French and their Indian Allies exacted more revenge for the Castine attack at Deerfield Massachusetts. Nearly 200 English men, women and children were killed or taken captive by Massachusetts tribes. Colonel Church asked the Massachusetts legislature to finance another “punitive expedition” but they refused although the legislature did authorize the bounties mentioned above. Church organized a private expedition and, according to Ganong:

resolved to ‘carry the war into Africa.’ Accordingly, Colonel Church was sent, about the end of May, 1704, with a force of 450 men, to ravage the French settlements. The expedition did great damage at Penobscot, Port Royal, Mines and Chignecto. Col. Church also visited Passamaquoddy, where he killed or made prisoners a number of the French settlers, who made no resistance, and should have received some consideration.

From this time forward the New Englanders became the aggressors, and set before them, as their ultimate object, the overthrow of the French power in Acadia.

Colonel Church’s motives were certainly questionable. None of the targets of his attacks were responsible in any way for the Deerfield massacre. The Passamaquoddies were a peaceful tribe who lived in harmony with nature and the few whites who trapped furs and fished in along the St. Croix. As Guy Murchie says in his history of the St. Croix Valley:

Little did the peaceful inhabitants there, white or Indian, dream that the recoil of an Indian attack on a Massachusetts settlement of which they knew nothing would so quickly hit them at Saint Croix. The Deerfield massacre of 1704 so stirred him that he begged Governor Dudley of Massachusetts to send him to exterminate all eastern Indians. Since the Governor and Council at Boston did not show much enthusiasm for his plan, Church is said to have gone all over his own Plymouth County and Cape Cod rousing the people for vengeance.

Church’s motivation has been questioned by many historians who noted that rather than attack those responsible for the massacre, the warlike tribes of Massachusetts, Church attacked peaceful and defenseless natives and Frenchmen along the coast. Woodrow Wilson, when President of the United States, wrote a newspaper column titled “A History of the American People.” Commenting in 1915 on the Deerfield Massacre of 1704 Wilson said:

And yet there had been no counter stroke by the English- except that Colonel Church of Massachusetts had spent the summer of 1704 destroying as he could the smaller and less defended French and Indian villages upon the coast which lay about the Penobscot and the Bay of Fundy.

An early Maine history summarizes Church’s raid:

Colonel Church was given a command of men and ships in 1704 and sent to Maine from Massachusetts with Passamaquoddy one of his objectives. Arriving at Matinicus he started a trail of depredations taking prisoners killing destroying homes. He arrived at Quoddy in whaleboats landed it is believed at Moose Island and again began to plunder the few homes he found here in this section, particularly up the St Croix River where even women and children found no mercy. He continued to the Bay of Fundy and destroyed Minas “now Horton” so an old history states. After three months of destruction, he returned to Boston. In this his fifth and last expedition he had taken 100 prisoners a great amount of plunder with the loss of only six men.

When Church arrived in Passamaquoddy Bay on June 7th, 1704 he first took prisoner a French woman and her children on what is believed to be Indian Island. He first questioned her on the whereabouts of the Indians according to Church’s report submitted to the Governor of Massachusetts after his return to Massachusetts,

“We then hastened away along shore, seizing what Prisoners we could, taking old Lotriel and his Family. This intelligence caus’d me to leave Col. Gorham, and a considerable part of my Men (and Boats) with him at that Island, partly to guard and secure those Prisoners, being sensible it would be a great trouble to have them to secure and guard at our next landing, where I did really expect and hope to have an opportunity, to fight our Indian Enemies.

Church then attacked an island to the east, probably Moose Island (Eastport) and early the next day advanced upriver to what is now Robbinston and the home of a Frenchman named Gourdan where he took the family prisoner and his men surrounded a house whose occupants refused orders to come out. When he asked his men what they were doing

They reply’d there was some of the Enemy in a house, and would not come out. I ask’d what house? They said a Bark house. I hastily bid them pull it down, and knock them on the head never asking whether they were French or Indians; they being all Enemies alike to me ……. I saw two men lay dead as I thought, at the end of the house, where the door was, and immediately the Guns went off, and they fired every man……

Sharkee’s encampment was just above Ferry Point, Dover Hill is to the right

Having received information from Gourdan that a Frenchman named Sharkee and a large contingent of Indians were camped upriver near what is now Ferry Point in Calais, Church decided to lead his men overland upriver to avoid detection by Indian scouts patrolling the river. His account, in which he describes himself in the third person, is as follows:

“The Colonel being ancient and unwieldy desired Sergeant Edee to run with him and coming to several trees fallen, which he could not creep under or readily get over, would lay his breast against the tree, the said Edee turning him over, generally had Cat luck, falling on his feet, by which means he kept in front. And coming near to Sharkee’s house discovered some French and Indians making a weir in the river and presently discovered the two Indians aforementioned, who call’d to them at work in the river, told them there was an army of English and Indians just by, who immediately left their work and ran, endeavoring to get to Sharkee’s house, who hearing the noise, took his Lady and Child and ran into the woods. Our men running briskly fired and killed one of the Indians and took the rest Prisoners. Then going to Sharkee’s house, found a woman and child to whom they gave good quarter and finding that Madam Sharkee had left her Silk Clothes and fine linen behind her, our Forces was desirous to have pursued and taken her, but Colonel Church forbid them saying he would have her run and suffer that she might be made sensible what hardships our poor People had suffered by them.”

The next day Church engaged in his last battle on the St. Croix at Salmon Falls just below Knight’s Corner. The Passmaquoddies expected this attack and had moved across the river to the point on which the Cotton Mill was later built.

But doubtless the Enemy had some Intelligence by the two afore-said Indians, before our Forces came, so that they all got on the other side of the River and left some of their goods by the Water-side, to decoy our Men, that so they might fire upon them; which indeed they affected. But through the good Providence of God never a man of ours was kill’d and but one slightly wounded. After a short dispute Col. Church ordered that every Man might take what he pleased of the Fish which lay bundled up, and to burn the rest, which was a great quantity. The Enemy seeing what our Forces were about; and that their stock of Fish was destroyed; and the season being over for getting any more, set up a hideous Cry, and so ran all away into the woods; who being all on the other side of the River, ours could not follow them.

Colonel Church then retreated downriver with his prisoners and presumably the scalps from those he had killed. His justification for the outrages he had committed and those he would commit before returning to Massachusetts with 100 prisoners and an unknown number of scalps is provided in his report to the Governor.

I question not but those French men that were slain, had the same good quarter of other Prisoners. But I ever look’d at it a good Providence of Almighty God, that some few of our cruel & bloody Enemies, were made sensible of their bloody Cruelties, perpetrated on my dear & loving friends and Countrymen; and that the same measure (in part) meted to them, as they had been guilty of in a barbarous manner at Deerfield, & I hope justly. I hope God Almighty will accept hereof, altho’ it may not be elegible to our French implacable Enemies, and such others as are not our friends..

We do not know whether the expedition was profitable, but we do know he did not return Downeast for nearly 300 years until he became the symbol of the International Parade and the Bicentennial. He reigned for 10 long years until the conscience of the community in the person of Jay Hinson put an end to his tenure and exposed Church for the villain he truly was.

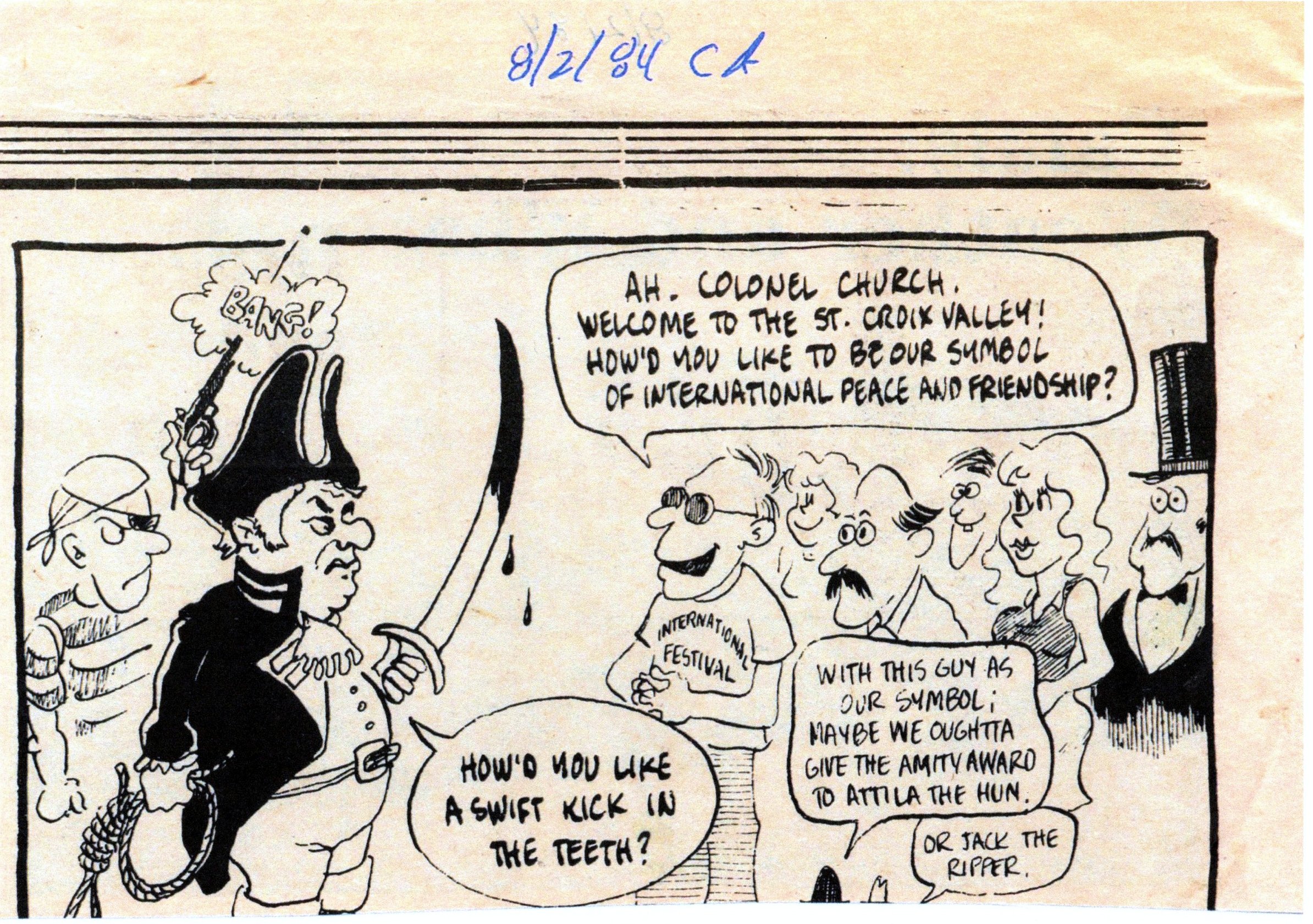

Calais Advertiser August 2, 1984

Jay Hinson’s Editorial August 3, 1984

Each August, as the International Festival rolls around, we suppose thousands of people are asking themselves why was Colonel Benjamin Church chosen as the symbol of the International Festival. The week-long event celebrates the close ties that bind the residents or St. Stephen, New Brunswick, Canada and Calais, Maine, America so it is with some surprise that we learned the other day that Colonel Church, depicted as a roly-poly, jolly kind or a summertime Santa , was actually a warped, blood-thirsty tyrant who liked to kill Indians and French people and just about anyone else who got in his way.

He was international, all right. He came from Massachusetts and raised hell in what was to become New Brunswick. He learned to fight Indians and led five expeditions against them, became incensed over the Deerfield, Massachusetts massacre of white people and begged the Governor or Massachusetts to give him a license to exterminate all eastern Indians.

Governor Dudley and his council in Boston turned down the rapacious Colonel Church who then went about rounding up a force of his own. He massed 550 soldiers, 14 transports, 36 whale boats and three armed vessels. He proceeded against Machias, invaded Deer Island, Campobello, Indians Island off what is now Eastport, Grand Manan, St. Andrew · and “Lincourt”, which is now Calais-St. Stephen.

Ganong, in his book, describes the good Colonel as “having an enormous size that was contrasted by his mentality”. Church was described by his colleagues as “fat, belligerent, ugly tempered, arrogant pompous”.

The selection of Colonel Benjamin Church to be the symbol of the International Festival was made by three gentlemen from St. Stephen, N.B., who played a big part in originating the International Festival eleven years ago. They did it, we are told, with tongue in cheek.

Colonel Church, during the past decade, has been portrayed on parade floats as that happy-go-lucky soul waving merrily at the passing crowds but his past reputation has now ruined all of that as far as we are concerned. What we’d like to see is Colonel Church replaced by someone who can spread true international cheer. Like who can we get to dress up like Everett Webb? Drop your suggestions off at the unemployment office and don’t forget to get a copy of his newest book, “The Answers To Everything”. You’ll find it in the library annex downstairs in the old post office next door to Barbara’s old wine and cheese shop.

His demise was long overdue. Donald Soctomah, historian of the Passamaquoddy Tribe, describes the feelings of those who suffered most from the Colonel’s depredations.

Wars sometimes create monsters and that is what I think of Col Benjamin Church, I do not have any good words about him. He killed and raped women and children in Tribal villages from Massachusetts to New Brunswick. Col Church sailed to the Passamaquoddy Bay to attack the Tribe but majority of the Tribe were in different locations but he did attack Salmon Falls (on St. Croix River) village where there was a few Passamaquoddy people living, his attack included capturing & killing Acadians. His brutality was documented in several newspapers.

Church was also responsible for raids on the Androscoggin and Penobscot Rivers during which Indian villages were destroyed, natives killed, and prisoners butchered. On the Penobscot he attacked Indian Island near what is now Old Town. We applaud Jay Hinson for ending Colonel Church’s reign as a symbol of our community but are distressed it took so long to expose Church’s true character.