The Romance of the Rails – that bygone era when travel was as simple as getting yourself to the train station on Hog Alley and buying a ticket for Bangor or Boston or San Francisco and then relaxing with a good book in your seat or in the club car with friends and a cocktail until the train pulled into your destination. This sunny view of riding the rails contained a good deal of truth, just not the whole truth; and whether 1900s rail travel would be suited for today’s lifestyle is questionable.

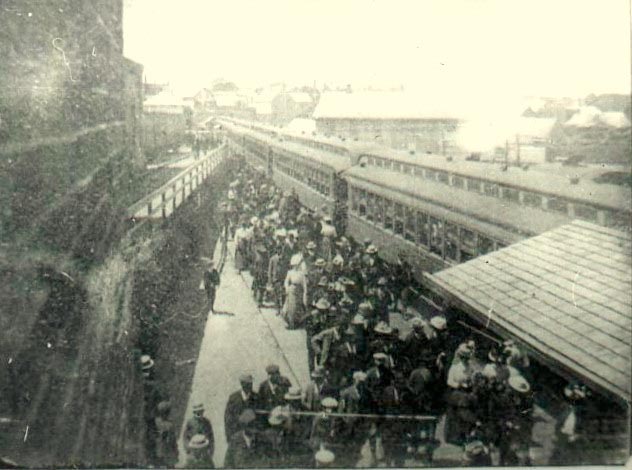

The crowd in the first photo above is disembarking from the train on Hog Alley in the early 1900s. The notation on the photo says it is a “holiday crowd” and it certainly is a large crowd as at least three passenger cars can be seen in the photo. However, train travel in the 1900s was not quite as convenient and comfortable as nostalgic writings and reminiscences would have us believe.

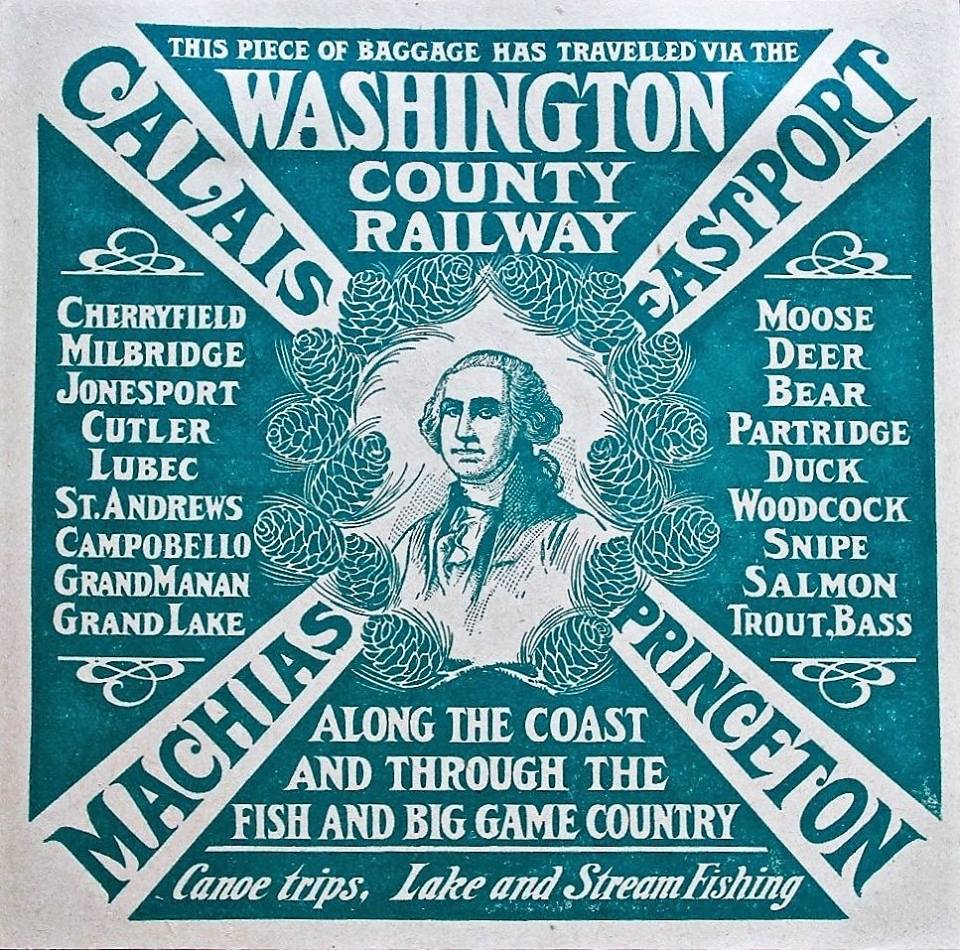

The local line, from Calais to Princeton with stops at Milltown, Baring, Sprague’s Falls and Woodland was, shall we say, an economy route with few amenities and a good chance of delays and “equipment failures”. Still it beat traveling by road in the early 1900s because the road was likely to be worse than a very bad camp road of today. Only in winter when the roads were frozen and sleighing good was it smooth sailing over our highways and byways.

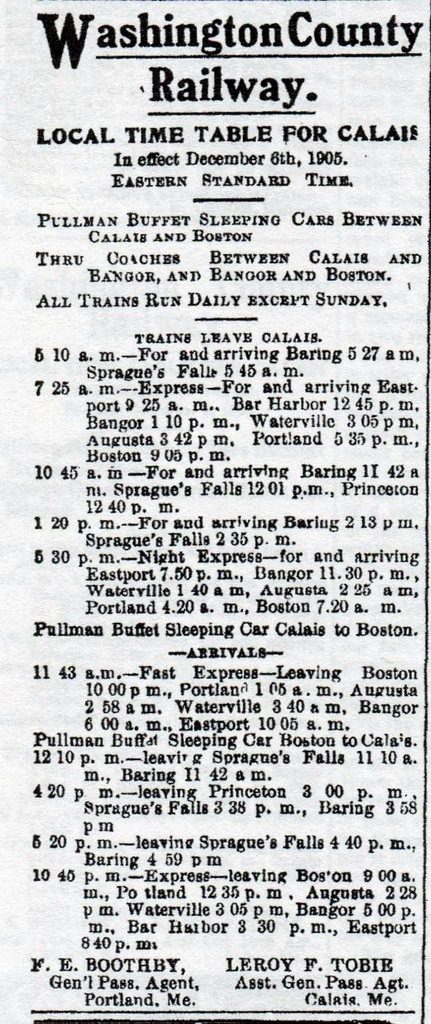

Take a look at the Washington County Railroad Calais schedule for 1905. The trip from Calais to Woodland (Sprague’s Falls) took from 25 minutes, [via] the Express, to an hour; Princeton was an hour away and Eastport two hours. The morning express to Bangor from Calais left at 7:25 A.M. and arrived in Bangor at 1:10 P.M. The night express to Bangor took six hours, and if you went on to Boston the entire trip could take 14 hours.

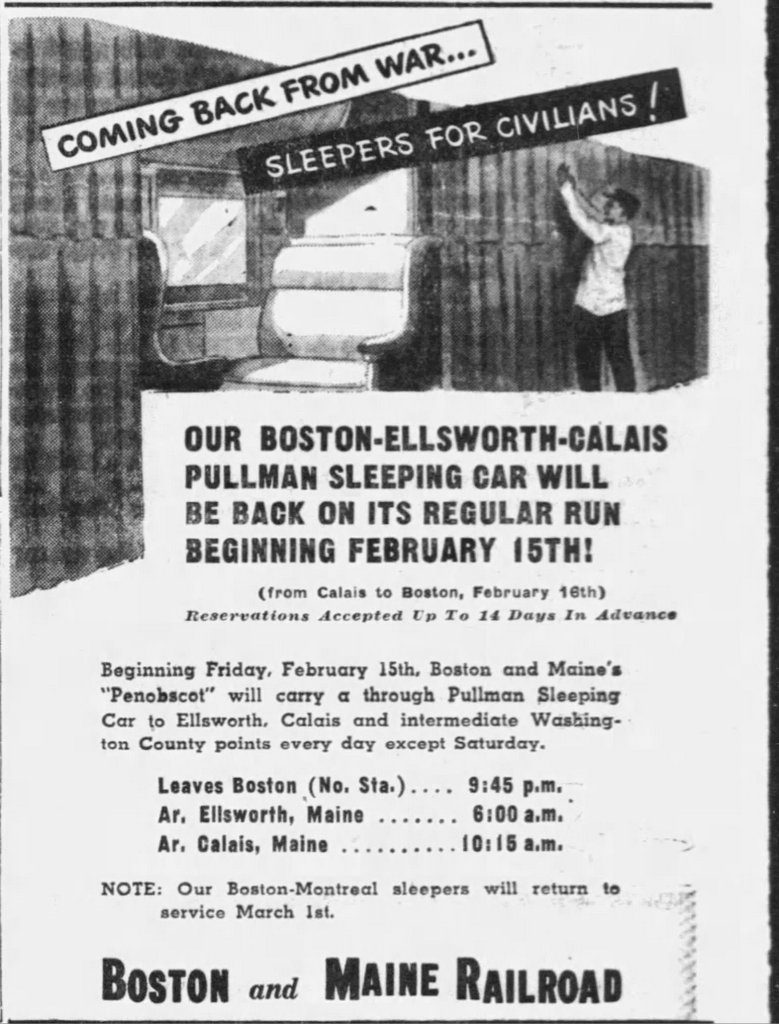

Of course, these were pretty fast travel times for 1905 and Pullman sleeping cars were available into the 1950s which was the preferred way to travel long distances as the trip from Calais to Boston took over twelve hours. The trains did get a bit faster in later years but not much.

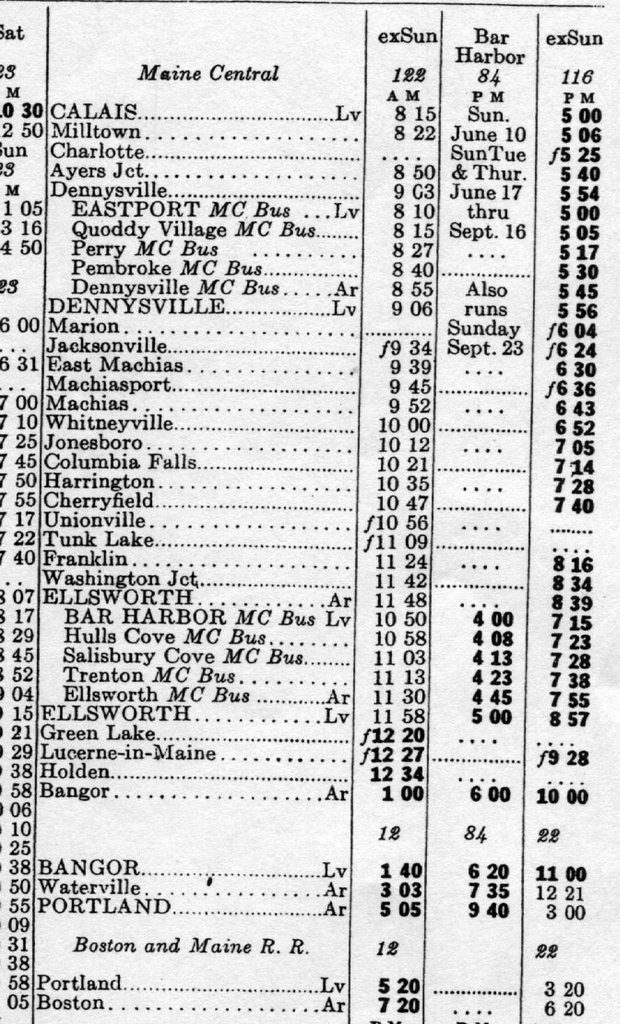

Even in the 1950s Bangor was still about five hours by train from Calais; and a day trip to Bangor would have started in Calais about 8:00 A.M. and arrived in Bangor about 1:00 P.M. with the return trip leaving Bangor at 4:30 arriving in Calais at 10:00 P.M. This left less than 4 hours to do whatever business you may have had in Bangor if you planned to return the same day. True the pace of life was much more relaxed in those days and probably much healthier; but we’re not sure how many of us would be able to adjust to such leisurely travel today.

The

seats in the passenger cars were fairly large by today’s standards,

about the same size as seats on today’s buses, far roomier than airline

seats and people were generally smaller back then. There may have been

club cars on the longer routes but probably not on the Calais to Bangor

run and for those impatient today when stopped for construction, the

train stopped at twenty two stations between Calais and Bangor.

Did we mention the top speed on the Calais to Bangor line was 40 miles an hour although it almost never managed to go that fast. The cost of tickets was 3-4 cents a mile. In 1951 when railroad passenger service was becoming a victim of the automobile, Maine Central was offering a special two cent a mile rate “between any two Maine Central stations in the State of Maine”. It did little good, the last passenger train left the Calais station for Bangor on November 23, 1957.

A complete railroad history of this area would require several volumes. Calais in fact had one of Maine’s first railroads which was a horse drawn affair from the mills in Milltown to the wharves on the Calais waterfront. Built in 1837 the tracks and ties were wooden and the horses pulled the cars laden with milled lumber on the wooden rails along the path by the river which is today the waterfront walkway. It was a short lived affair as neither the horses or rails could withstand the weight of large loads of freshly milled lumber and the $35,000 enterprise went bust in just a few years.

The lumber barons were forced to haul the lumber from Milltown to the wharves using six horse teams – the usual four horse team could not negotiate the hill on North Street where Tim Horton’s is now located. In fact only the most experienced teamsters and the best horses could manage the hill even under the best conditions. When the ground was wet the hill became almost impossible. Some other method of transporting lumber from the mills to the wharves was needed.

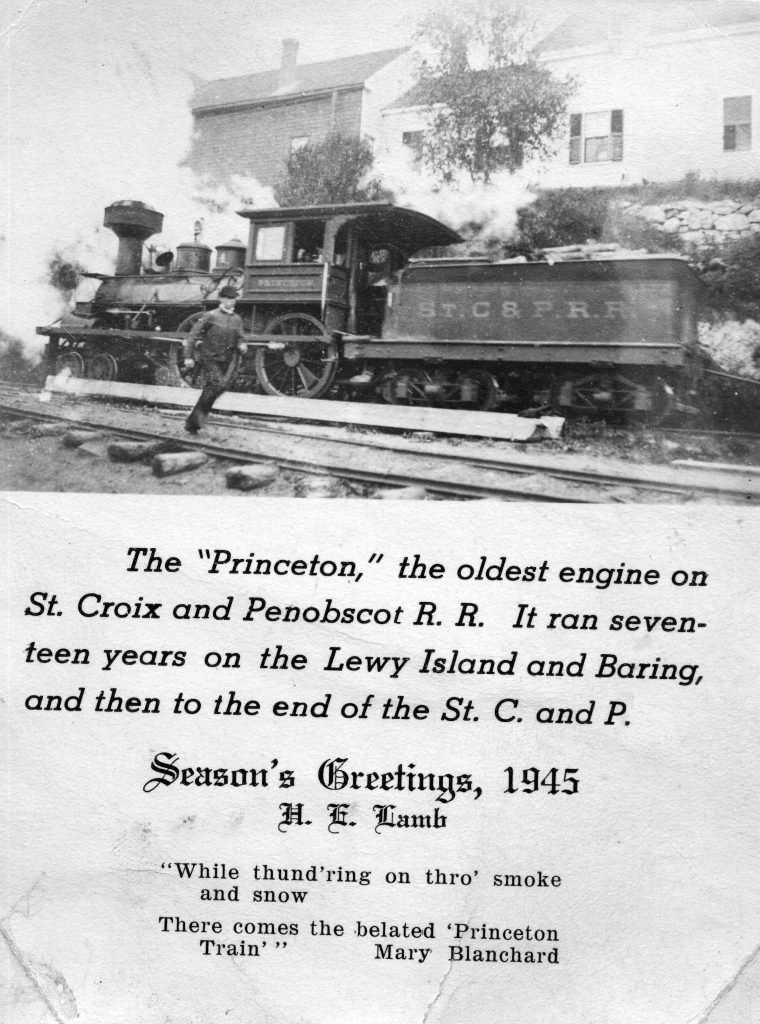

Thankfully by 1857 railroad technology had improved greatly as had the necessity of transporting logs from the Princeton area to the mills downriver and the Lewey’s Island Railroad was formed. The Lewey’s Island Railroad replaced the wooden tracks with steel rails, the horses with a steam locomotive and transformed the movement of lumber to the mills and from the mills to the wharves. It later became the Lewey’s Island and Baring Railroad, the St. Croix and Penobscot and finally the Washington County Railroad which was itself bought out by the Maine Central in the early 1900s.

Unfortunately for this area it was almost 1900 before we had a direct connection with the rest of the country. Our neighbors in St. Stephen were connected to the international line at McAdam decades earlier by the Shoreline Railroad but refused to allow Calais to construct a railroad bridge across the St. Croix to give this region access to McAdam. This created a lot of hard feelings in the valley, not being considered very neighborly but in fairness the Canadians profitable shoreline railroad was owned by rich and powerful men on both sides of the border who didn’t want their golden goose killed by competition from the American side.

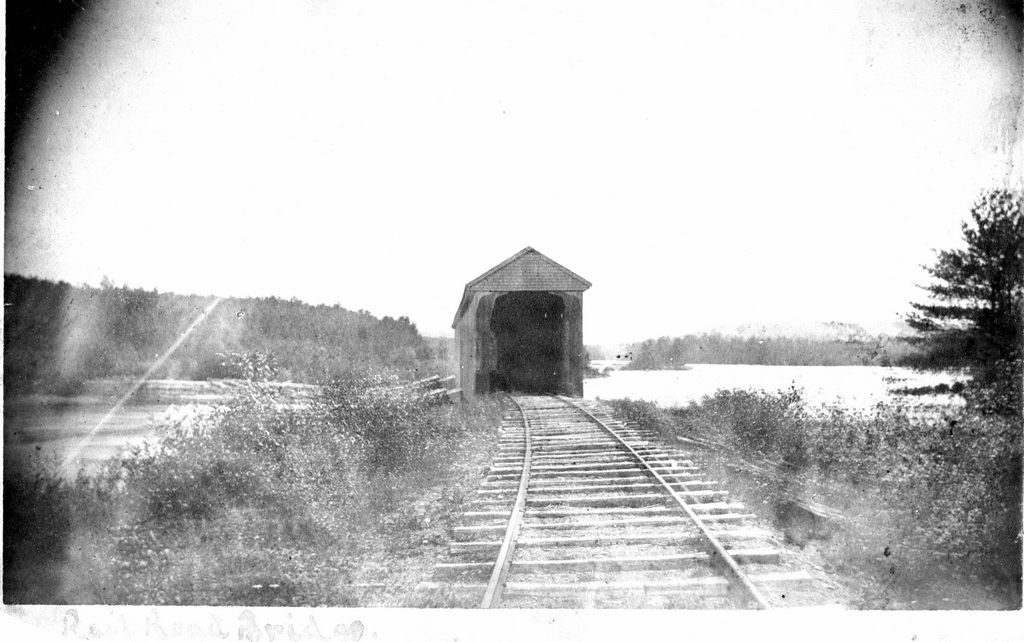

The Canadians were not adverse however to two railroad bridges over the St Croix at Baring and Woodland as neither connected with their direct line to McAdam. It was certainly an odd situation, a railroad that crossed at Baring into Canada and back into the United States at Woodland. There was no customs or immigration presence on either side of the border and this could create a problem for law enforcement. Historian Ned Lamb reported on one such instance

There had been an excursion to Princeton and one man celebrated entirely too much, and they had to arrest him and put the cuffs on to handle him. He was put into the smoking car to go to Calais. When the train got over the bridge and into Canada, some of his friends pulled the car coupling and stopped the train, and then demanded that the officer take the cuffs off and let him go as he was then on Canadian soil. That had to be done, and the man walked the rest of the way, probably with some of his friends to steer him straight. Life can be complicated along the St. Croix.

There was also a potentially disastrous incident in 1861 involving the destruction of Black’s Bridge in Woodland. Again according to Ned:

Just why he did it we do not know. He may have thought he was smart, he may have had some spite against the railroad, he may have been just “cussed”, but a certain man set fire, and burned the bridge at Spragues’ Falls. He must have done it at night because the smoke was not noticed in the morning. The next morning the train left Calais about 7:30 behind the Princeton engine. The set was as follows: Conductor, Charles MacDonald; Engineer, Wallace Haycock; Fireman, John McCurdy; Brakeman, Billie Burton. The place where the bridge wasn’t was noticed in time for the engineer and fireman to jump, but not in time to keep the engine from going into the hole and dragging the tender after her. The old engine carried a big dent in her boiler all the rest of her days. Who was the man? We might tell you, but perhaps it is just as well to let the name rest in the limbo of forgotten things. Anyway he served a term of two years in Thomaston for his little bonfire. He rode over the road years later, but perhaps he was too drunk to remember the fire.

The Calais Advertiser was didn’t spare the perpetrator but was angrier still at the residents of Bailey Hill in Woodland:

It is reported that persons residing on Bailey Hill saw the fire and knew it was the bridge that was burning and also knew that the train would be down the next morning, and if not informed of the fact, would run into the river and cause the destruction of considerable property and perhaps the lives of a number of persons; yet never moved a finger to warn persons connected with road of the danger that awaited them. Instead of doing so, they kept a lookout for the train the next morning, saw it as it came along down the road, and watched it until it pitched headlong into the river, and even then, never went to the spot to see what damage had been done or render assistance if needed. All of which they could have done if they chose. If this statement is true, they are little better than wilful murderers, and ought to be imprisoned for life and not be allowed to live among civilized beings. And we should have strong suspicions that they had a hand in bringing about the catastrophe.

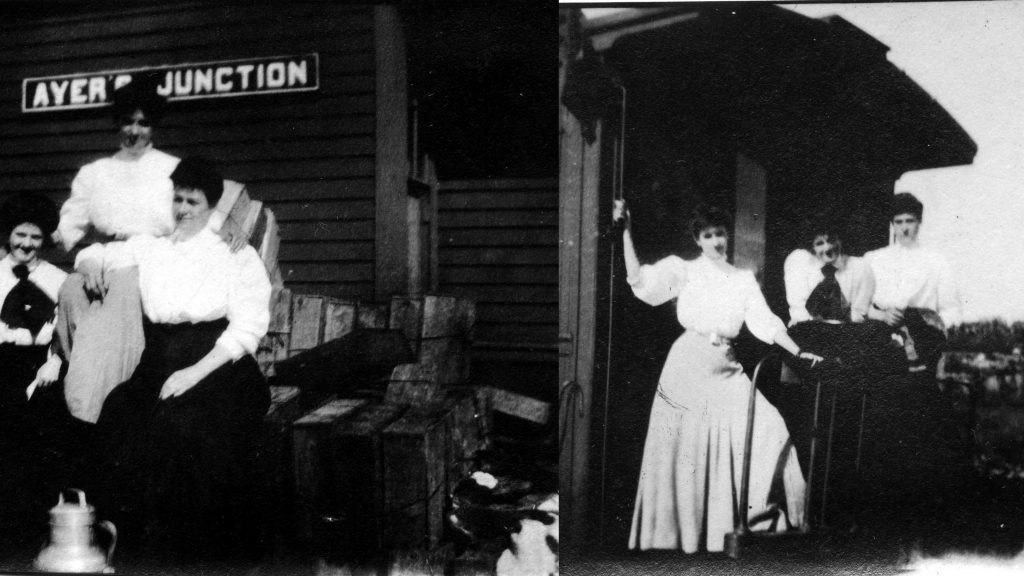

We’ll end with a photo of Ayer’s Junction and Emma Boardman and friends awaiting the train to Boston. Emma was a Calais Boardman, an accomplished artist and a graduate of the Boston School Of Art who worked as a designer for many years for one the most popular magazines of the day – “Modern Priscilla”. Born in 1885, we can date this photo of her to about the First World War when she was working in Boston. Perhaps she’s on her way back to Boston or possibly she’s come from Boston and been dropped off at Ayer’s Junction to await the train to Calais. Ayer’s Junction was an important station in those days. Now we know it as the parking lot of the Downeast Trail which begins at Ayer’s Junction and ends in Ellsworth. The trail follows the old railroad bed and is primarily a four wheeler trail these days. If any of you off-roaders can find the remnants of Tunk Lake Station between Unionville and Franklin Stations we’d like to have a photo.