So, matey, you’re tired of the endless Maine winters, the bitter cold, snow and daily chores of cutting wood and thawing water, not to mention the swarms of insects which will plague you with the arrival of spring when the real work of the year begins with plowing, planting and hoping there is enough rain so the crops don’t fail?

Perhaps a change of scenery is in order – a drastic change, and one which can be easily arranged by drifting down to the Calais or St. Stephen waterfront and signing on to the next ship leaving town for such exotic places and warmer climes as Jamaica and Barbados, where the rum is served in barrels, not shot glasses, or the South Seas, where it never snows and you hear the friendly natives live on fruit falling from the trees and fish scooped with a net from the shore and, if that gets boring, you can always sign onto a ship in the China trade and become fabulously wealthy.

However, before signing on to one of the Murchie or Boardman ships leaving the port you might want to consider the words of the Bard:

If the poem is not as clear as it could be, and poetry tends to be confusing at times, the point is “Following the Sea” was a very dangerous occupation in the days of sail, probably more dangerous than any other other occupation (except being a soldier in Napoleon’s army) and it remains so today. In the list of the most dangerous occupations in 2018, it is second to woods workers. The occupations we tend to think of as dangerous (police, firemen, soldiers etc) don’t even register in the top ten.

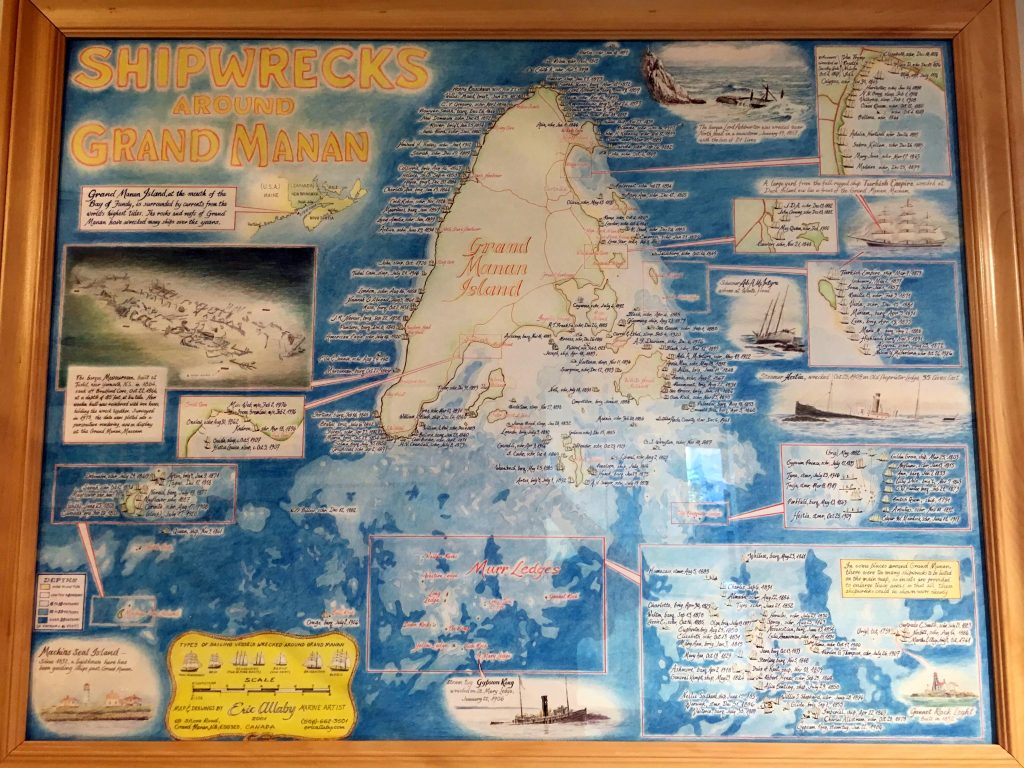

In the days of sail, being called before the mast was fraught with danger and while there were many ways to lose your life on sea voyages, the most common was a shipwreck. Numerous books have been written about shipwrecks in the Bay of Fundy and Passamaquoddy Bay, but even these works don’t do credit to the dangers associated with the life of seaman from the early 1800s until the age of steam in the 1900s when ships became less susceptible – although not impervious as we shall see below with the Hestia – to the vagaries of winds and ever changing seas.

Harrowing newspaper accounts of suffering and death on the sea can be found from the 1820s in the Eastport Sentinel and by the 1830s in the Calais Advertiser and the St. Croix Courier. When St. Croix valley ships were national news, which was depressingly often, tragedy and death was sure to be involved. Below are just a very few of the dozens of accounts of Downeast shipwrecks.

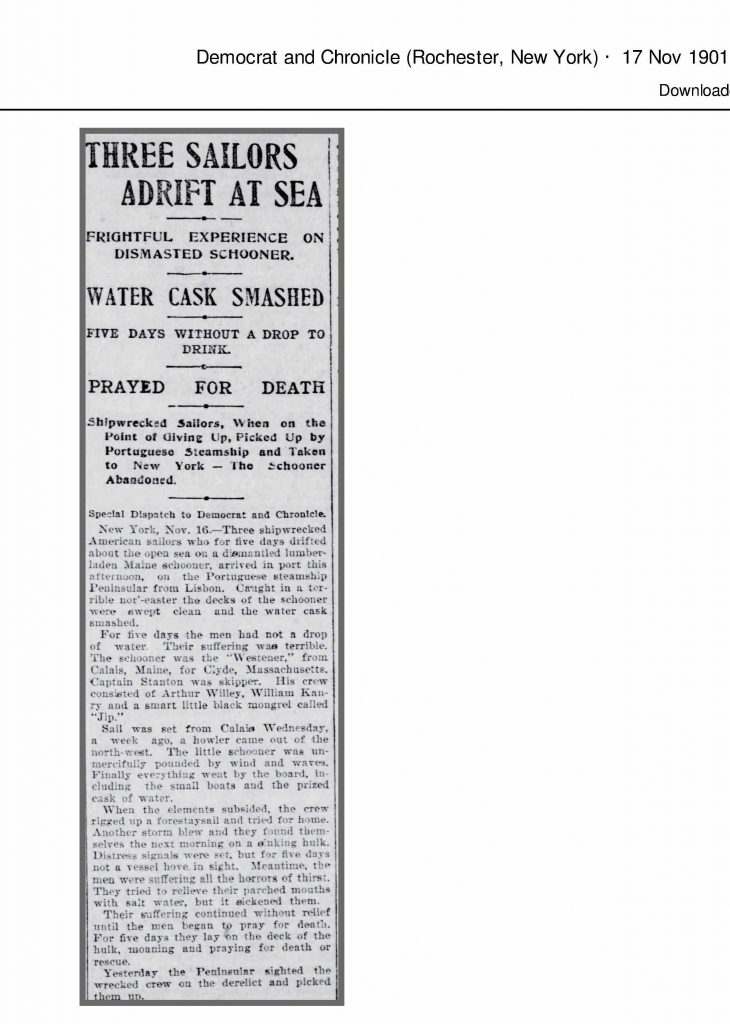

Sailors pray for death:

THREE SAILORS ADRIFT AT SEA

FRIGHTFUL EXPERIENCE ON DISMASTED SCHOONER.

WATER CASK SMASHED FIVE DAYS WITHOUT A DROP TO DRINK.

PRAYED FOR DEATH

Shipwrecked Sailors,

When on the Point of Giving Up, Picked Up by Portuguese Steamship and Taken to New York

The schooner Abandoned.

Special Dispatch to Democrat and Chronicle. New York, Nov. 16 1901

Three shipwrecked American sailors who for five days drifted about the open sea on a dismantled lumber-laden Maine schooner arrived in port this afternoon on the Portuguese steamship Peninsular from Lisbon. Caught in a terrible nor’easter the decks of the schooner were swept clean and the water cask smashed. For five days the men had not a drop of water. Their suffering was terrible. The schooner was the “Westerner,” from Calais, Maine, for Clyde, Massachusetts. Captain Stanton was skipper. His crew consisted of Arthur Willey, William Kaury and a smart little black mongrel called “Jip.” Sail was set from Calais Wednesday, a week ago. A howler came out of the north-west. The little schooner was unmercifully pounded by wind and waves. Finally everything went by the board, including the small boats and the prized cask of water. Then the elements subsided, the crew rigged up a forestay sail and tried for home. Another storm blew and they found themselves the next morning on a sinking hulk. Distress signals were set, but for five days not a vessel hove in sight. Meantime, the men were suffering all the horrors of thirst. They tried to relieve their parched mouths with salt water, but it sickened, them. Their suffering continued without relief until the men began to pray for death. For five days they lay on the deck of the hulk, moaning and praying for death or rescue. Yesterday the Peninsular sighted the wrecked crew on the derelict and picked them up.

Grand Manan was a particularly dangerous obstacle to ships entering and exiting Passamaquoddy Bay, as is evident from the map above showing the history of shipwrecks on its treacherous coast. Books have been written about Grand Manan’s shipwrecks, famous painters have memorialized them on canvas and a good example of one is the wreck of the Hestia in 1909.

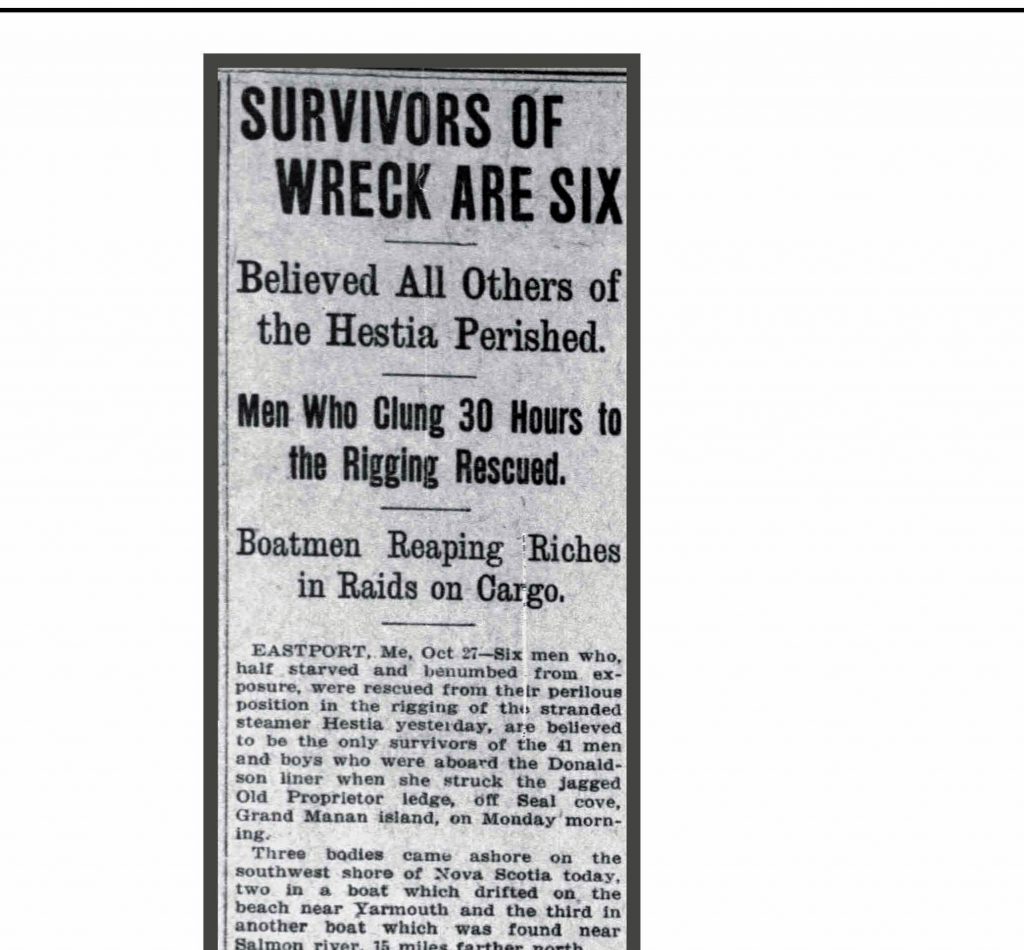

SURVIVORS OF Wreck Are Six Believed All Others of the Hestia Perished.

Men Who Clung 30 Hours to the Rigging Rescued, Boatmen Reaping Riches in Raids on Cargo.

EASTPORT. Me. Oct 21–Six men who, half starved and benumbed from exposure, were rescued from their perilous position in the rigging of the stranded steamer Hestia yesterday, are believed to be the only survivors of the 41 men and boys who were aboard the Donaldson liner when she struck the jagged Old Proprietor ledge, off Seal Cove, Grand Manan Island, on Monday morning. Three bodies came ashore on the southwest shore of Nova Scotia today, two in a boat which drifted on the beach near Yarmouth and the third in another boat which was found near Salmon river, 15 miles farther north. There is little doubt that these are the two boats which started off from the wreck, each well loaded with men. Up to tonight the bodies had not been identified. Recovering somewhat from their awful experience, the men who escaped their companion’s fate were able today to give more definite information regarding what actually took place after the steamer went on the ledges. Third Mate Stewart said that the Hestia reached the end of her last voyage on Monday morning, instead of Tuesday morning, as had previously been supposed, and that he had his live comrades, who had been unable to find places in the boats which were launched when it was decided to abandon the ship, remained lashed to the rigging for 38 hours, without food or water, before they were taken off by the lifesavers. As far as can be ascertained tonight those on board the Hestia comprised Capt Newman, a crew of 35, three cattlemen and two boys. The tug Lord Kitchener from St John was about the scene of the wreck until late. She had been dispatched by the agent of the Donaldson line at that place, and it was thought possible that she might put into Grand Manan and take off five of the six who were rescued. The sixth seaman, Bernard Breen, was the most seriously affected by the 38 hours’ strain, but is expected to recover. Forsaken today was the quest of fish which supplies the Eastport and Lubec sardine factories. Every boat in the Grand Manan fishing fleet was busy cruising about the scene of the wreck. Men in boats, too, pulled in every bag, crate, bale and bundle possible, and a rich harvest was reaped in the absence of the underwriters, who have not yet appeared to start the salvage operations. It is safe to say that their spoils of today will find a hiding place before morning.

Some of the boatmen were not satisfied with one trip’s result of varied cargo but set out a second and in a few cases a third time. Most made preparations also for an early start tomorrow, for the cargo of the Hestia was tonight still being washed from her holds and set adrift by the tides and waves. Unless the underwriters place early restrictions on the operations there will be several days of harvest before the freight is finally exhausted. When the round-up shall have closed, they will be forced to secrete the goods as, it is believed, the underwriters will send agents ashore to search for the Hestia’s cargo. From the Hestia’s cargo one of the things most sought has been Scotch whisky of which there were over 1000 cases aboard.

The 1909 sinking of the Hestia illustrates the terrors associated with life as a sailor and also demonstrates the tendency of coastal communities to take advantage of the opportunity offered by salvage from the wrecks. Some may find this callous, but life was hard on the rocky coast of the Passamaquoddy, and the locals rationalized their plunder of wrecks such as the Hestia as legitimate plunder from a wealthy shipper. The cargo from a local ship would almost certainly have been returned.

It was common for the ship’s captain to take his wife and if the children were older the entire family went along on voyages which could sometimes be months or years in duration. There are several accounts of women behaving heroically in times of distress on the high seas

A Sea Heroine. 1885 Detroit Free Press

The tales of actual occurrences at sea are seldom outdone by those of fiction. Indeed, Clark Russell, the great nautical authority on marine romance, says that an author cannot invent anything so strange as that which may happen at any moment at sea. The schooner Ferris was mere days out from Calais, Maine, last week when she sprang badly a leak. The captain, two men and a boy labored hard at the pumps until they were well-nigh exhausted. Then the captain’s wife, a small, pretty woman of 18 years, came on deck and took the wheel. Hour after hour the frail woman labored at the rudder against the great waves that broke upon it in tremendous shocks. But her aid enabled the men to work at the pumps all through the night until the youngest sank on deck with blood oozing from his eyes and mouth. Then she took her place at the pumps, allowing the schooner to drift. It was her encouraging words which kept them to their work. Sail after sail passed without seeing their distress, and the schooner settled deeper and deeper into the sea. At last they were rescued, and their vessel went down before they had hardly abandoned it. But among the freshest and most cheerful of them all was the young and pretty wife of the captain whose crew’s life, as well as her own, she had saved by her pluck and endurance, Detroit Free Press.

At other times the ending was not so happy.

Georgia Todd: 1870

PERILS OF THE SEA.

Captain’s Wife and Part of the Crew Drowned.

From the Boston Journal, Dec. 28, 1870

The British ship Euxine, Captain Owen, from Liverpool, reached this port on Sunday, having on board a portion of the crew of schooner Georgia Todd, of Calais, Maine. We learn the following particulars from the Captain of the unfortunate vessel: The schooner Georgia Todd, of Calais, Capt. W. T. Hill, sailed from St. Stephens, N. B. Dec. 15, with a cargo of white pine boards, bound to Havana, and at 6 P. M. on that day she was nearly up with Machias, Seal Island bearing about south. The wind was northwest, and increasing, with a very heavy head sea. At 6 P. M., the vessel pitching heavily, it was found necessary to take in more sail, which was done, and the vessel was kept off south-south west. It was noticed that the schooner acted strangely, and wouldn’t steer well even under all head sail, but as she was a little out of trim, it was attributed to that cause. At 8 P M Sea Islands bearing north-northeast fifteen miles, it was suddenly found that the vessel was nearly full of water and filling so quickly that the captain had barely time to get his wife out of the cabin in her night clothes; not being able to save a single article of wearing apparel. The wind at this time changed to north-northwest, blowing a gale. The vessel’s course was turned to the southward. She went on very well for three hours, or until about midnight, when she broached to and turning over on her side, threw all hands into the sea. The first and second mates, the steward and the captain’s wife were all drowned. The remainder regained the wreck, and, after much trouble, succeeded in cutting the weather main rigging, when the vessel righted, and the survivors took refuge on the quarter and remained there, suffering terribly from the cold until Sunday afternoon, the 18th. Fortunately, during the day the British schooner Victoria hove in sight, and at once made an effort to save the lives of the perishing men, although this vessel was also disabled and in a very leaky condition. They succeeded, however, in getting two of them off the wreck, but in coming alongside the vessel their boat was stove in and rendered useless, which accident prevented their return for the other two men still remaining on the wreck. Being determined to save them if possible they lay by all night, hoping to get the seamen safely off in the morning. But at daylight on the 19th, a ship was discovered to leeward, which proved to be the Euxine, from Liverpool for Boston, and as the Victoria was in such a poor condition as to be considered hardly seaworthy, the two rescued seamen were transferred to her. Capt. Owens, of the Euxine, after hearing the story of the shipwreck, immediately made sail and stood for the Georgia Todd, trusting to be in time to save the rest of the crew. On coming up with the wreck the men were found to be still alive. They were promptly removed to the ship, where their wants were kindly attended to, and with their other companions were brought to this port. They express the warmest gratitude to the officers of the Euxine for the kind treatment received at their hands. The following are the names of the lost: Mrs. Hill, Captain’s wife; Alfred Price of St. Stephen, mate; Job Knight, of Calais, second mate and James Kennedy of St. Stephens, steward. The Georgia Todd was a schooner of 217 tons, built in 1868, at Calais, Maine, where she was owned by Mr. W. H. Boardman.

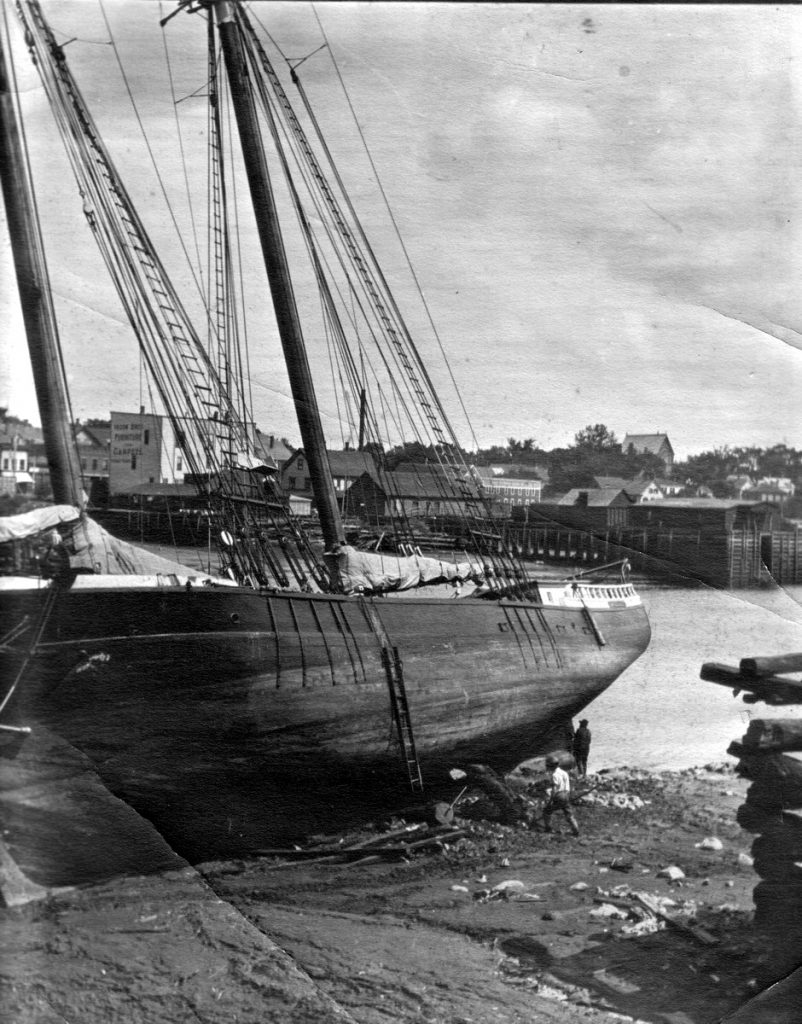

If you were the sailor on a small coastal schooner such as the Moonlight above on the shore at Calais your loss might merit only a short notice in the paper:

The schooner Grace of Calais went down in 1898. The papers reported:

A schooner supposed to be the Grace, of Calais, Maine, is ashore two miles southwest of Wood End life-saving station with masts gone, cabin gutted and no signs of life. It believed her crew has perished.

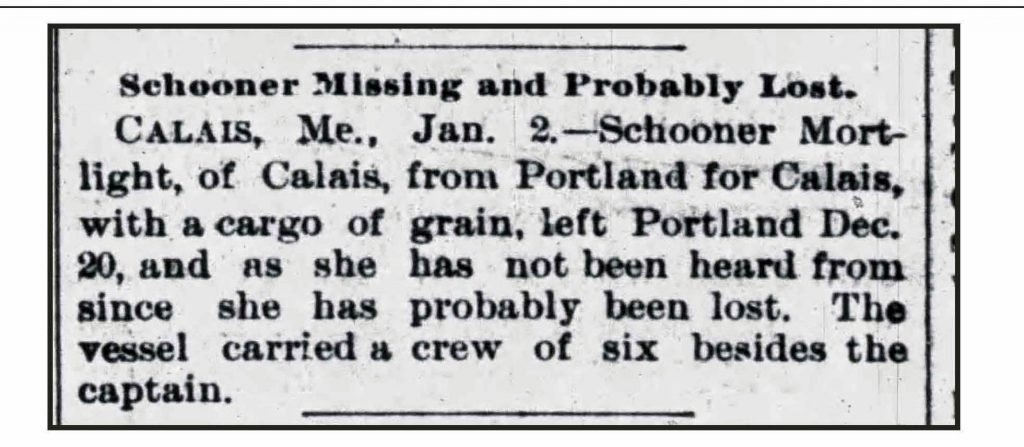

Often ships simply disappeared without a trace with nothing to explain the loss or provide any closure to the families of the sailors. For example a newspaper report in 1876 stated:

Boston Globe 1876:

From a memorandum found on one of the bodies washed ashore, it is supposed that the vessel which was lost on Sable Island was the schooner Mary Reeves of Calais. Me. She was in command of Capt. Bracy and all hands were lost. The Mary Reeves was a small vessel of 99 tons register, built in 1854 and owned by Nickerson and Rideout

Shipwrecks weren’t the only hazard for sailors. There are numerous reports in the papers of sailors blown into the sea during gales, washed off deck in heavy seas and fatally falling to the deck from the rigging. An entire crew of Calais sailors was murdered by natives when their ship ran ashore in South America and not a few lost their lives in the dens and haunts of foreign ports.

Some part of the mystery of the disappearance of the schooner Julia Warr was only recently solved by the discovery of the graves of two of the seamen from the ship on Little River Island near Cutler. An account of the wreck was published in the Fall River News of 1898, although at the time little was known about how and where the ship capsized. The poem which followed the article is touching and expressed the anguish and grief of many a Downeast family in the days when the sea was our only practical connection to the world

The Julia Warr: 1897:

THE JULIA A WARR Owners Give Up All Hope of the Vessel and Her Crew.

Captain Warr Leaves a Widow and Six Children

Mate Wilson Married Only Three Days Before Making This Trip

Hoping against hope the agent of the missing schooner Julia A Warr has at last almost given up the expectation of ever seeing his vessel again. She sailed from the mouth of the river at Calais Me Dec 18th and immediately ran into a howling northwest gale and high heavy seas. It was too late to put back as no sailing vessel could beat to windward against that wind and sea and the only alternative was to keep the vessel going with a hope that the weather would moderate and the schooner could get across under the lee of the land but instead of the gale’s letting go it increased with hurricane force and mountainous seas accompanied with fierce snow squalls in laying his course. Capt. Warr had to run in the trough of the sea and was probably driving the vessel for all she was worth to hurry across into smoother water when she was struck by an unusually heavy puff of wind on the top of a heavy sea and with a high deck load of lumber she tripped and rolled over turning completely bottom up and giving the men no chance for their lives. The first report brought in by the steamer Boston of passing a large lot of lumber adrift and bulwarks of a white vessel was the first intimation that anything had gone wrong with the schooner but so many vessels have white bulwarks and are lumber loaded that her agent was not in the least alarmed The next report was from the fishing schooner Vesta which arrived in Gloucester last Friday and reported passed a vessel bottom up in lat 42.44 long 66.47 The vessel was a center-board schooner of about 250 tons with a dark brown bottom and sides painted white This description was too near that of the missing vessel for comfort and the agent started for Boston and Gloucester Wednesday to find out more of the particulars taking photographs of the schooner with him. The Gloucester captain said the vessel bottom up had a long straight keel very flat floor smooth white sides and lots of loose shingles scantlings spruce boards and planks floating all around her. This is exactly what the Julia A Warr had on her deck load and the description of her hull and stem fitted it. When the captain took the photograph of the vessel that was taken while on a railway he turned it bottom up and looked at it a moment and said “That’s the very vessel I saw bottom up” When the question was asked about the yawl boat the captain said the sunken hull was too much submerged to see whether it was there or not. There is a very slight hope that the vessel lay long enough on her beam ends to allow the crew to put off in it as it would probably be washed from the hull if left and it has not been reported with the other wreckage. Still the captain of the fisherman said this might not be the vessel. On looking on his chart and allowing that the Julia A Warr was capsized the day after leaving Calais she would be very near the place where this wreck was found 25 miles south from Seal Island and 200 miles east from Highland Light. The Captain is known at all the principal ports on the Atlantic coast by his genial even disposition and quiet ways. He made friends wherever he went and had a host of them in this city. He was counted as one of the best skippers on the coast bold and fearless always driving his vessel for all it was worth and making quick trips. In fact he broke the record at Calais this last summer making a trip to Fall River with a cargo of lumber and returned in 13 days In his efforts to make a quick run this last time he encountered the gale and with the vessel hampered with a high deckload of lumber the forces of nature proved too much for him and the results are probably as described. He leaves at his former home below Calais a wife and six children four boys the oldest 17 years and two daughters the youngest four years old. Another sad feature of the case is that the mate Mr. Fred Wilson who had been with Capt. Warr two years was married only three days before leaving on this trip. The crew list of the vessel was as follows: Captain George Warr mate Fred Wilson of Jonesport Me, cook J Moses seamen William Warr and Campbell McKay. There is a bare possibility that the men on the vessel were picked up by some fishing schooner or some outward-bound sailing vessel and will be brought into port all right later but as the days go by the chances grow less There will be many a sad and tearful eye in this city at the thought that Capt. Warr will never bring his trim fast sailing craft into this port again.

There is waiting, anxious waiting,

for the tidings of the missing

And tearful eyes are looking

in sadness to the shore

And the mother’s heart is aching, as

the child she’s fondly kissing

Whispers softly from its cradle,

“Will papa come no more?”

There is waiting, anxious waiting

And the days and weeks are

flying

Yet no coming of the missing ever

glads the watcher’s eye:

And the waves for aye are surging,

with a wild and mourning sighing,

When in dreamless rest, the Sailor

with his shattered vessel lies.

On March 28, 1898 the remains of the Julia Warr, bottom up, washed ashore at Shinnecock Life Saving Station on Long Island New York.

We’ll

end on a more uplifting note. At times vessels would go missing and

hope would gradually fade that those on the ship would ever return home

or their fates be known. This seemed the fate of the Emma Louise which

left Calais in late December 1892 on a short voyage to Connecticut.

After nearly two months all hope had been lost for her crew until in

late February 1893 the following report was received from Bristol

England:

On Tuesday the barque Sophie, of Christiania, from Sapelo, Georgia, for Sharpness, with a cargo of pitch pine, arrived at Kingroad, Bristol, and landed the captain and crew of the Emma Louise, a waterlogged vessel, which was sighted off the coast of the United States. The Emma Louise was an American schooner belonging to Calais. Maine, and was commanded by Captain Calder. She had a cargo of timber for New-Haven, Connecticut, and left Calais on December 28th. Shortly after the voyage was started heavy gales were encountered and frightful weather experienced off Cape Cod. The masts, sails, and rigging were swept away, the boats stove in, and the cabins swamped. Nearly all the provisions were spoilt, and at last the captain and crew of four men had positively nothing on which to subsist but a couple of small salted fish. On the 17th day of the voyage after the schooner had been for a long time tossed about at the mercy of the wind and waves the Sophie was sighted off Cape Hatteras. In spite of the tremendous sea which was running Captain Donvig ordered a boat to be lowered, and at great peril to themselves, a crew, in charge of the second officer, managed to reach the Emma Louise. By this time the schooner was completely waterlogged and was on the point of foundering when the captain and crew were rescued. They had undergone severe privations, and all their effects were lost. The Sophie continued her voyage to England and arrived in Kingroad after a stormy passage, lasting 29 days

One can only imagine the joy with which this news was received in Calais.