The Wickachee Dining Room is perhaps the oldest restaurant in the St. Croix Valley, although it is possible Carmen’s Diner in St. Stephen is also in the running. Originally, the restaurant was built to serve the guests at the Wickachee Rooms, a guest house next door. This house was built by master ship builder William Hinds in the 1840s and, directly behind the Hind’s house at the bottom of Barker Street, was the Hinds shipyard, famous in its day for building fast and seaworthy schooners and ships for local and international trade.

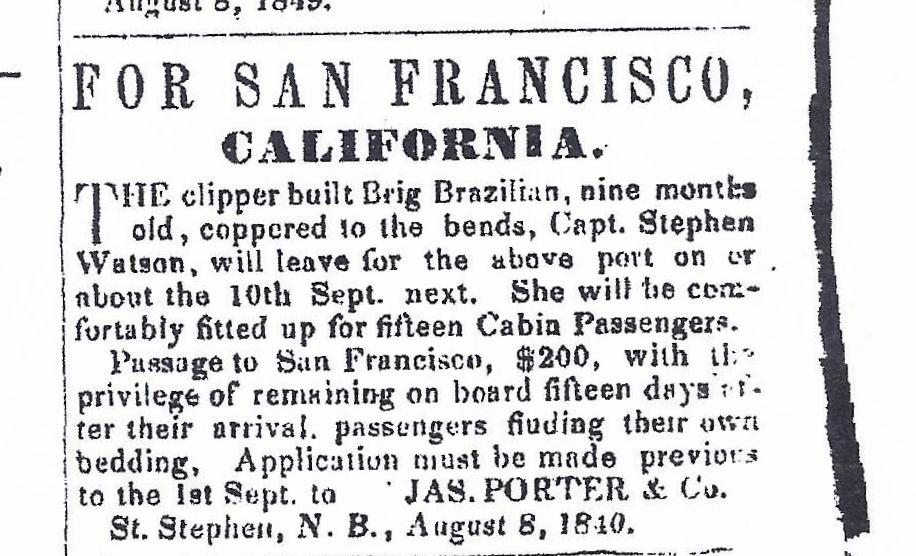

In 1850, Henry Eastman, owner of a shipyard just across the river in St. Stephen, came to Hinds with a very odd request: he wanted Hinds to build him a ship of 700 tons without decks, which he planned to tow to the Ledge four miles below St. Stephen and sink. If this sounds a bit puzzling, remember that the year was 1850 and the fever which had consumed the country had spread to the St. Croix Valley. In fact, as the St. Croix Valley was a center of shipbuilding and trading, locals had much better access to the goldfields than most on the east coast. Hundreds went, so many in fact the editor of the Calais Advertiser, John Jackson, lamented that the valley would be ruined if the exodus continued. It did. From the Calais Advertiser August 8, 1849:

The Gold Rushers had descended on an undeveloped land with little industry and lacking the basic resources to sustain the thousands who came to make their fortunes. Ships with as many local adventurers as they could carry were leaving Calais as quickly as they could be built, and, loaded with lumber and other basic supplies, then worth more than gold itself on the west coast. However, after arriving many of the supplies still had to be delivered up the Sacramento River to the interior, and for that what was needed was a steamboat, not a sailing ship which could be becalmed for days in the river. There were none in California, nor were there facilities to build one, and therein lies the reason behind Captain Eastmen’s strange request. The rest of the story was best told by William Ganong of St. Stephen in a 1916 article in a San Francisco newspaper:

STEAMBOAT SENT TO CALIFORNIA IN VESSEL’S HOLD: 1850.

The S.B. Wheeler – California’s Pioneer River Steamboat Was Shipped from the St. Croix in The Hold of a Sailing Vessel – Nov. 16, 1916

By Wm F Vroom

In 1916, the days of transcontinental railways and telegraph lines, it is difficult to realize that, within the memory of many persons now living, California was but a strip of Mexican territory stretching along the Pacific coast, little known and almost inaccessible from the Atlantic states. The white population was confined to the missions of the Franciscan fathers and the few settlements established by adventurers whose wanderings by land or sea had ended there.

Almost simultaneously with the ratification of the treaty with Mexico, which added the tract now known as California to the United States, came the discovery of gold, when the scene suddenly changed, and men from all parts of the union rushed to the El Dorado which promised fabulous wealth to all who dared to join in quest.

The sudden increase of population in 1849 of course created a demand for all things pertaining to the civilized life, not least of which must be included the modern means of transportation. Small steamers for river traffic were needed, but how to obtain them was a difficult problem. Under existing conditions, they could not well be built there, and they could not undertake the voyage around the South American continent from the Atlantic Coast. Nevertheless, a steamer arrived in California and went into commission on the Sacramento river in 1851.

It was Captain Henry Eastman, shipbuilder, of St. Stephen who conceived and carried out the idea of sending a steamer around the Horn in the hold of a sailing vessel – Captain Eastman’s yard was in the town of St. Stephen on the St. Croix river, which there forms the boundary between the State of Maine and the Province of New Brunswick. Here, early in 1850, the keel of the ”Fanny”, a bark of 700 tons, was laid down by Wm. Hinds, master builder, and in the fall of the same year the vessel was launched.

The Fanny was built with a view to carrying the steamer “S.B. Wheeler” as her first cargo, to California, and the means by which this was accomplished was ingenious and novel, as well as successful. The vessel was built with deck beams and knees secured by screw bolts which could easily be removed. After launching, she was towed to “the Ledge” a deep-water harbor on the St. Croix, and there ballasted with stones, was scuttled. It should be remarked here that the spring tides at this point rise and fall not less than twenty-six feet maximum.

At high tide, the Fanny’s deck beams having been removed, the steamer was floated over the sunken vessel and gently settled down into her hold as the tide ebbed, grounding as I was informed by an eye-witness, “within three inches of where Mr. Hinds wanted her.” At low tide, the holes in the vessel’s bottom were stopped and she rose with her cargo on the flood.

The S.B. Wheeler was a small steamer formerly plying between Eastport and Calais on the St. Croix. I have not been able to ascertain her tonnage or dimensions but know that her height from keel to deck about filled the space between the deck and keelson of the bark. The deck beams of the Fanny were replaced, some of them passing through the steamer’s cabin, the keel of the steamer was made fast to the keelson of the bark and the masts of the latter were stepped on the steamer’s keelson. Ties and braces were inserted wherever necessary to prevent the possibility of shifting and the Fanny was rigged and made ready for sea. Coal was then stowed in the hold outside of the steamer which further contributed to the stability of the cargo.

Among those to whom I am indebted for information concerning this incident was the late Mr. Ed Martin of Santa Cruz, Cal., who has given me more firsthand testimony than I have obtained from any other source.

Regarding the voyage, Mr. Martin says: “The bark “Fanny” sailed from the Ledge, December 24, 1850, for San Francisco, under command of Captain Foster, an American; Wm. Wallace, first mate; James Cassels, second mate. The Fanny anchored at Eastport, Maine, and spent the Christmas of 1850 at that port. The weather was cold and stormy, and we were glad to leave Eastport the day after Christmas. In a few days’ sail we were in a warmer climate. After a voyage of 133 days, we reached San Francisco.

“This novel way of carrying a steamer was the subject of much discussion. It was prophesied that the vessel and her cargo would never reach their destination; but, in spite of all forebodings, the Fanny arrived in San Francisco in good shape and with her cargo intact. The Fanny was taken to Benica and there relieved of her steamboat. Soon afterwards the S.B. Wheeler was running on the Sacramento river or rather on the San Joaquin, between San Francisco and Stockton. After running on this route for some time, she was taken off and sent to the Sandwich Islands, where she was wrecked on one of the reefs.

” Among those who came out in the Fanny were John Lockhead, who was engineer on the Wheeler during her run on the San Joaquin river; Alexander Campbell, a lawyer of St. Stephen, afterwards elected judge of a district court of San Francisco; J.B. London of Chamcook, N.B.; Samuel Robinson, of St. Stephen, carpenter, and Edward Kelly, caulker . My impression is that Eastman did not realize much from this trip, or from the revenues of the S.B. Wheeler. John Lockhead the engineer, settled in San Francisco, sent for his family and became quite prominent in his profession.”

Mr. Martin served as a sailor boy during this voyage and never missed his “trick at the wheel.” Mr. Eastman offered him the position of second mate on his return trip, but the offer was declined, as the young man had no great liking for the sea life. Subsequently, he took the practice of law and settled in Santa Cruz, where he was for many years a leading citizen. Mr. Martin died at the age of eighty-one, soon after writing the above narrative.

I am greatly indebted to Mr. R.L. Porter, of Salinas, Cal., for placing me in communication with Mr. Martin, who was then, with possibly one exception, the only survivor of the party who accompanied the Wheeler to California. Mr. Porter distinctly remembers the launching of the Fanny.

In view of the recent transportation of submarines by stowing them inside of the “kangaroo” steamers, this incident of sixty five years ago reminds me that “there is nothing new under the sun”.

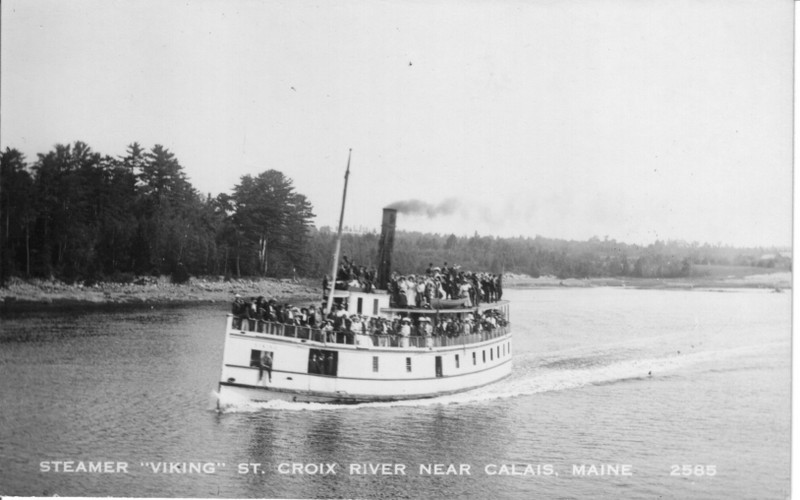

We have no photo of the Fanny or the Steamship Wheeler. According to one account the Wheeler was about the size of the Viking, pictured above, a steamer that plied the waters of the St. Croix in the early 1900s. It was not a large steamer but certainly adequate for the Sacramento River and a vast improvement over poling barges up the Sacramento or carrying supplies overland

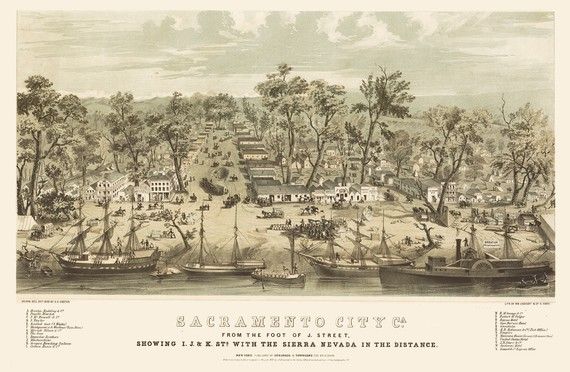

We did find this drawing of the Sacramento River in the early 1850s, and to the far right there is a steamship which could conceivably be the Wheeler, but it looks too large for the ship described in the article.

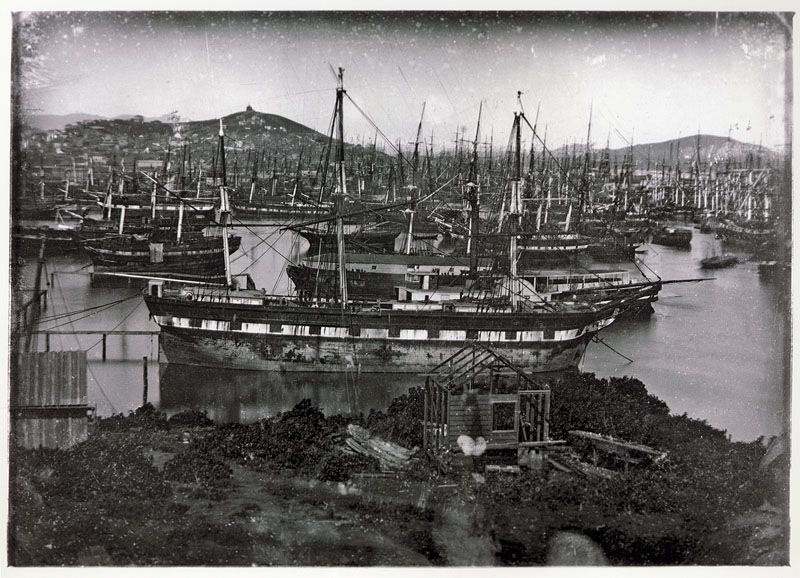

The refloating and refitting of the Fanny after the Wheeler was removed from the hold was indeed a very bad idea. The photo above shows ships abandoned in the harbor at San Francisco in 1850. Ships from the east coast often found the crew had left the ships before the passengers, bound for the gold fields and leaving the captains (those who didn’t follow the crews) too shorthanded to make the return voyage.

Many of the passengers and some of the crew of the Fanny remained in California and several made their mark in this new frontier. Alexander Campbell of St. Stephen is a good example. Campbell was a highly regarded lawyer and churchman in St. Stephen and St. Andrews. He was married to Susan Milliken of St. Stephen, had six children and a thriving law practice in which he trained some of the province’s best attorneys. His father was the High Sheriff of the province. Yet he cast caution to the wind and chanced all on a very risky roll of the dice. They came up seven for Andrew. In San Francisco he became a well respected citizen and eventually a judge. We presume, although we don’t know, that his family joined him on the west coast. He was in a minority of local “Gold Rushers” from the St. Croix Valley who prospered on the west coast, none of them as far as we know struck gold but rather found opportunity in law, business, publishing…

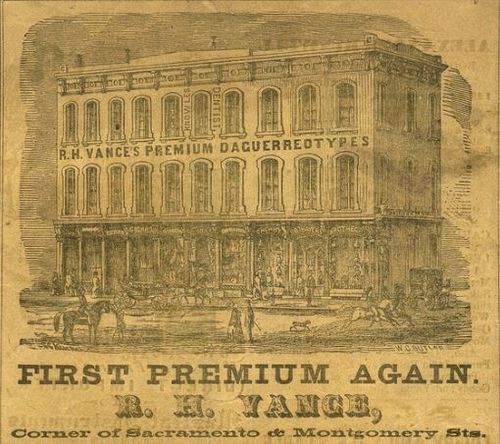

… and photography. Robert Vance, son of “Old Vance” of Baring and Calais was one of the first photographers in the region and his early photographs remain historical treasures. We’ve written of Vance and the Gold Rush in the past but just as a reminder of the conditions found by many locals in California during this now romanticized era we’ll end with a reprint of some observations from letters home written by a Calais boy, I.S. Kelsey:

As to conditions generally in San Francisco and in the gold fields the letters home were in agreement with I.S. Kelsey who wrote “I think it would take a salary of $5000 per year to induce me to become a resident of this city- The wind has the air continually full of dust. It is the driest dustiest City I ever saw- Calais dust is nothing to it.” Unfortunately the gold dust in hills was not as plentiful as the dust in the air of San Francisco. In letters to the Frontier Journal in March of 1850, I.S. Kelsey describes the life of a miner. About the quantity of gold he says “You may enquire, is there no gold in this country? I answer that it is sown broadcast over a large extent of the country, but the trouble is, the quantity in many places on a given space, will not pay the expense of removal.” The process of extracting the gold from the earth was back breaking work which required shoveling the ore into a device similar to a baby’s cradle. “You cannot obtain so much as a tablespoon full of dirt, without using the pickaxe and it must be swung vigorously to penetrate the soil, it is so cemented together. Having dug up the dirt and emptied it into the square box at the head of the cradle, we seize the staff and proceed rocking back and forth to the tune of Long Lucy, continually pouring water in with a long handled dipper, which we hold in the right hand: the water and the motion dissolve the cemented earth, and it passes through the box, drops into the apron, and descends to the bottom of the cradle. Having passed through 20 or 30 pails full we remove the box and apron, turn on water and wash off a portion of the dirt and gravel, then draw off our plugs and suffer the balance to run into a tin pan. We then, after a peculiar manner, wash off everything until we come to the glittering metal, sometimes obtaining from the above quantity one dollar, sometimes eight. Two hundred and fifty buckets is a good day’s work for two men.” Not surprisingly Kelsey advised his friends in Calais not to be in hurry to follow him to California. “I advise all who are unfitted for, or unacquainted with hard labor and exposure, to remain where they are- to the strong and energetic I give no advice. Gold cannot be shaken from the trees.”