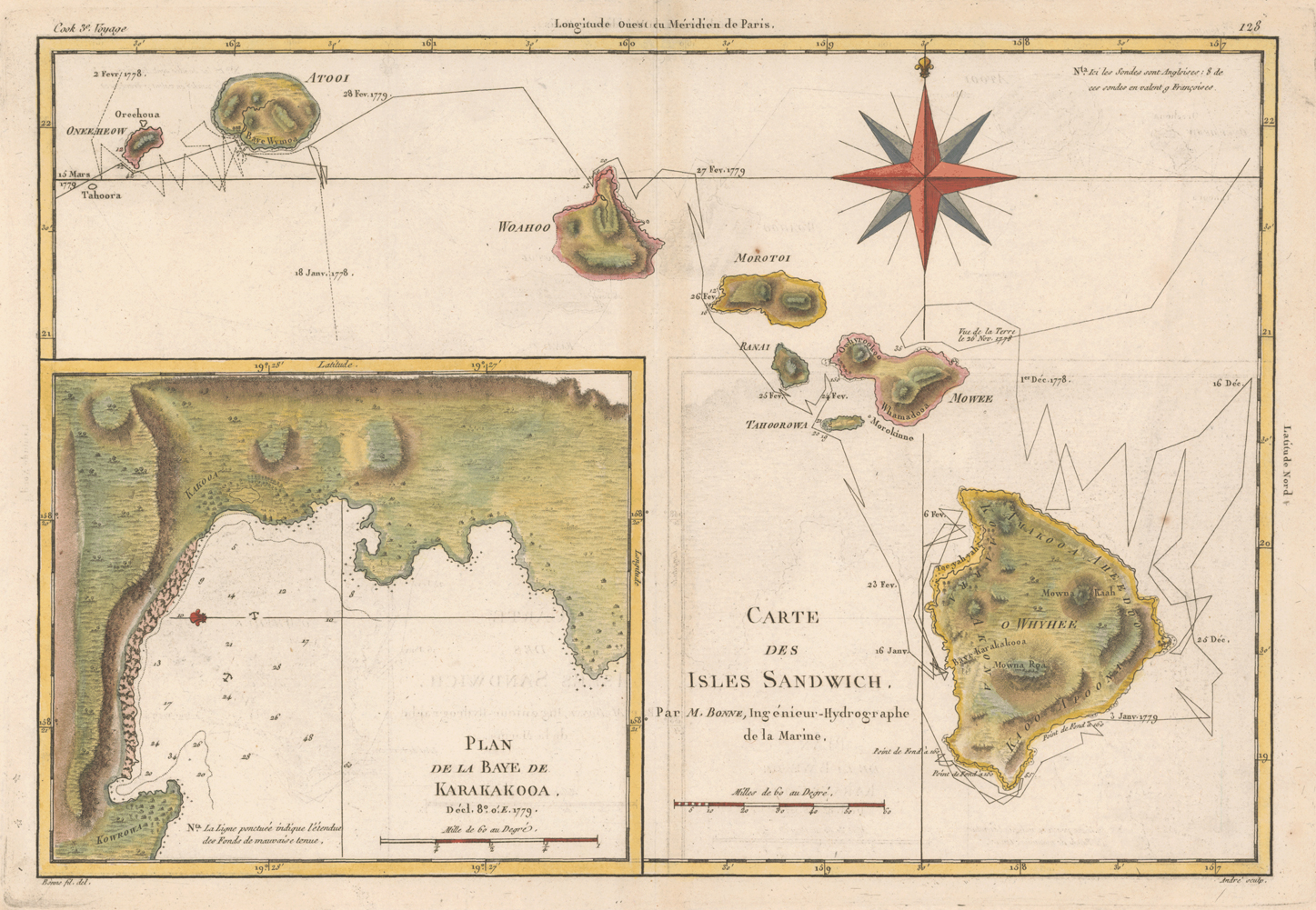

According to Google Earth Calais is exactly 5210 miles from Honolulu Hawaii. The only two towns in the United States more distant from Honolulu are Eastport (5229 miles) and Lubec (5230 miles) so it is curious that Calais in the 1800’s had such close connections with what were then called the Sandwich Islands.

In the 1850’s the Sandwich Islands were of little commercial value other than as a midway point for Pacific travelers. The United States maintained a small diplomatic presence in Lahaina near present day Honolulu but there were few nonnatives living on island at the time and not much in the way of U.S. interests to protect. However there was a U.S.consulate and naturally a U.S. consul and one of the first consuls was a Calais lawyer, George M. Chase who in 1853 assumed the post of U.S. Consul to the Sandwich Islands.

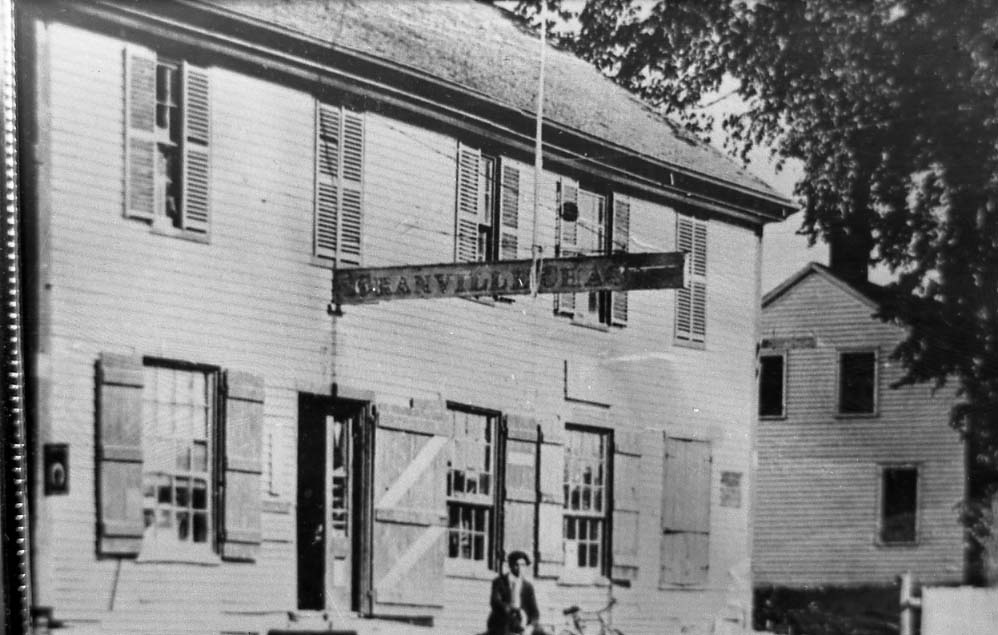

The Chase family was very prominent in Calais in those early days. They owned businesses and lumber mills up and down the river- Granville Chase, whose Baring store is pictured above, for all practical purposes owned the Town of Baring.

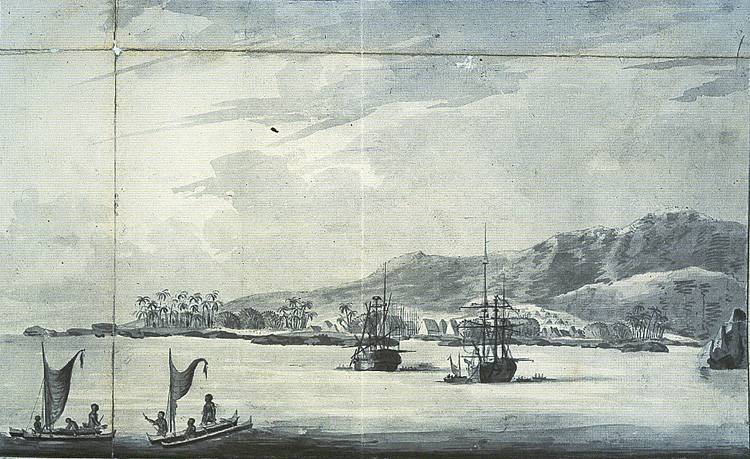

Daniel Chase, another relative of George, operated the most successful chandlery and hardware business in Calais in the 1800’s on Hog Alley where the former information bureau is located near the library. He founded the Chase Poor Fund from which the City still receives annual payments. George Chase was a prominent lawyer in town and served as senator from Washington County in 1850. Given his success in Calais one has to wonder why he would accept the position as consul to the Sandwich Islands which, while they look idyllic in the painting above, were a very, very long way from Calais. He gave his son, George Jr, the option of joining the family in the islands or attending college. George Jr decided against college and for adventure and the family took the Calais-New York-Isthmus of Panama –San Francisco-Sandwich Island route to the islands. This was not for the faint hearted in 1853. The journey took months and many travelers succumbed on the way to yellow fever or bandits on the trip across the isthmus or drowned traversing dangerous Cape Horn. George Sr. and the family arrived safely but George Sr.’s health suffered. The climate not surprisingly did not agree with him and his health deteriorated rapidly even though he was under the care of a physician from the mainland. Curiously or perhaps by amazing coincidence his doctor in Lahaina was almost certainly a fellow named Charles Curtis who had married a young lady from Calais named Sophia Dyer and had practiced medicine in Calais before moving to Lahaina in the Sandwich Islands. Curtis could not save George who died in 1857 and was packed in a pickling barrell for the trip home and burial at the Calais cemetery. Both Doctor Curtis and his wife are also buried in the Calais cemetery. George Jr returned to the mainland and became one of the original settlers in Kansas City Missouri.

George Chase’s experience in the island should, one would have thought, given pause to others offered the position but George’s pickled body hadn’t yet rounded Cape Horn on the way home when another Calais lawyer, Anson Chandler, agreed to assume the post. Chandler had also been a senator from Calais and was in his 60’s when he arrived in the islands. His tenure there was unremarkable although the humid tropical climate could not have been good for his health for he too died a couple of years after returning to the mainland and is buried in the Calais cemetery.

Chandler did manage to wrangle a position for William Pike of Calais in the consulate. William was the son of one of Calais’ founding fathers and brother of James Sheppard Pike. He was a generally unsuccessful businessman and investor who, according to his brother, adopted a policy of ignoring his creditors much to the detriment of his reputation. He may well have found refuge from them for the years he spent in the Sandwich Islands but he returned from the islands without restoring his fortune and also died within a couple of years of his return to Calais.

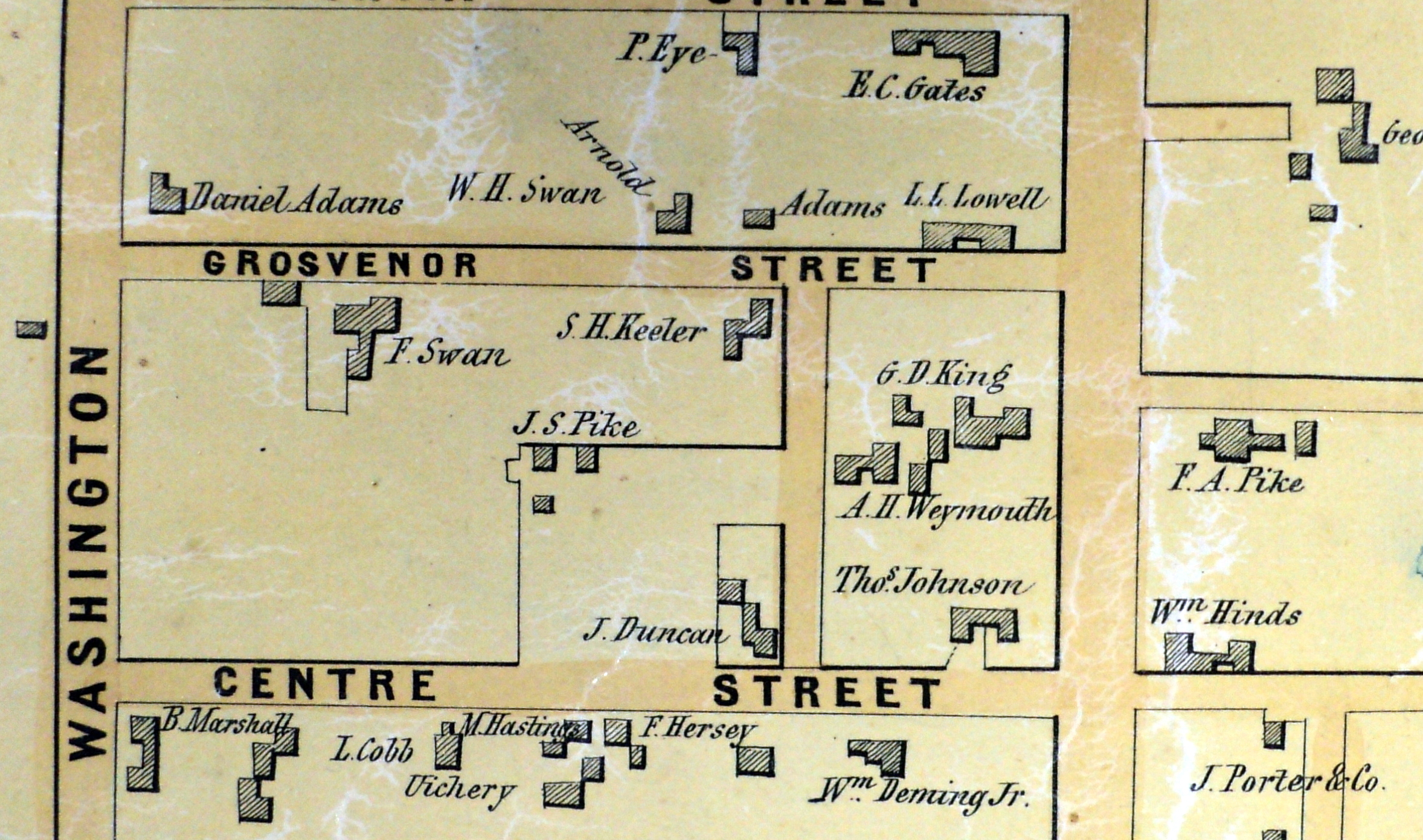

By far the most interesting connection Calais has with Hawaii involves a Calais man named Frank Hastings. Frank was the son of Matthew Hastings and he grew up on Barker Street, on the map above it was still called Centre Street. Swan Street was then Grosvenor Street. He attended Calais schools and eventually joined the diplomatic corps and in 1877 he was assigned to the Hawaiian legation as permanent vice-consul. He was bright and ambitious and married an Hawaiian heiress soon after arrival in the islands.

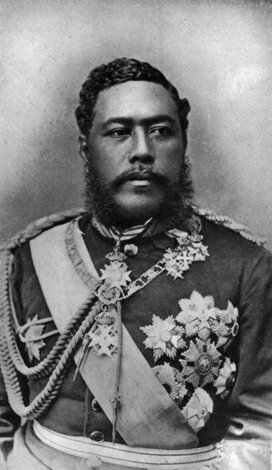

Hastings quit the diplomatic service sometime in the 1880’s, went into business in Hawaii and become deeply involved in local affairs. He was popular with the then King Kalakaua, pictured above and was appointed by the King as his Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The king enjoyed the good life much more than the mundane duties of ruling his kingdom and effectively ceded these responsibilities to American business interests which by the 1880’s discovered there was money to be made in Hawaii, especially by exploiting local labor to grow pineapple. Sanford Dole was one such businessman. All went well for the oligarchs until the King died in 1891.

Hastings quit the diplomatic service sometime in the 1880’s, went into business in Hawaii and become deeply involved in local affairs. He was popular with the then King Kalakaua, pictured above and was appointed by the King as his Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The king enjoyed the good life much more than the mundane duties of ruling his kingdom and effectively ceded these responsibilities to American business interests which by the 1880’s discovered there was money to be made in Hawaii, especially by exploiting local labor to grow pineapple. Sanford Dole was one such businessman. All went well for the oligarchs until the King died in 1891.

After the King’s death the crown princess Liliuokalani became Queen. An educated, articulate woman of fierce determination she began immediately to undo the king’s legacy and restore authority and power to the crown. This naturally infuriated the business interests as they wanted the U.S. to annex Hawaii and depose the Queen but President Cleveland was reluctant to support them.

Frank Hastings, it appears, had thrown his lot with the business interests, known as annexationists who in January 1893 mounted an armed revolt and overthrew the queen. The photo above shows US Marines in Hawaii during the revolt. The Queen believed the Marines would support her opponents if she refused to surrender although it remains unclear they had orders to do so. Liliuokanali agreed to step down. A provisional government under Sanford Dole was formed and Calais’ Frank Hastings was appointed by Dole as the new Republic’s representative to Washington. There then occurred a strange incident in Washington in which Hasting’s played a major role. The US Government was ambivalent about Dole’s provisional government and did not officially recognize Dole. Hastings, in Washington to represent Dole’s government, got wind of secret instructions from President Cleveland which were to be carried from Washington by the U.S. minister to Hawaii Albert Willis to Dole and Queen Liliuokanali. These instructions effectively backed the Queen in the power struggle and promised the annexationists amnesty if they allowed the Queen back on the throne. Hastings had a friend in the State Department steal the original of the instructions which he copied, returning the original before anyone realized it was missing. The copy he sent by fastest dispatch to Dole in Hawaii. When Ellis arrived from Washington to deliver the President’s decision Dole, knowing the President was siding with the Queen, refused to see him or accept the dispatch and insisted his government would declare war on the United States if it persisted in interfering with the affairs of the new Republic. Cleveland backed down and the next administration annexed Hawaii.

Frank Hasting followed the path of his Calais cohorts who got themselves too involved in Hawaiian affairs. He died very young in 1897 at the age of 45 still serving President Dole in Washington. It was probably all those years in the tropical heat and humidity of one of the most beautiful places on earth that did for him. Before his death he returned one last time to Calais to visit friends and family. In the end Queen Liliuokanali got some measure of revenge, she lived to a ripe old age, trusted and revered by Hawaiians.