[Note: This article, written by Lura Jackson, was originally published in The Calais Advertiser in 2017.]

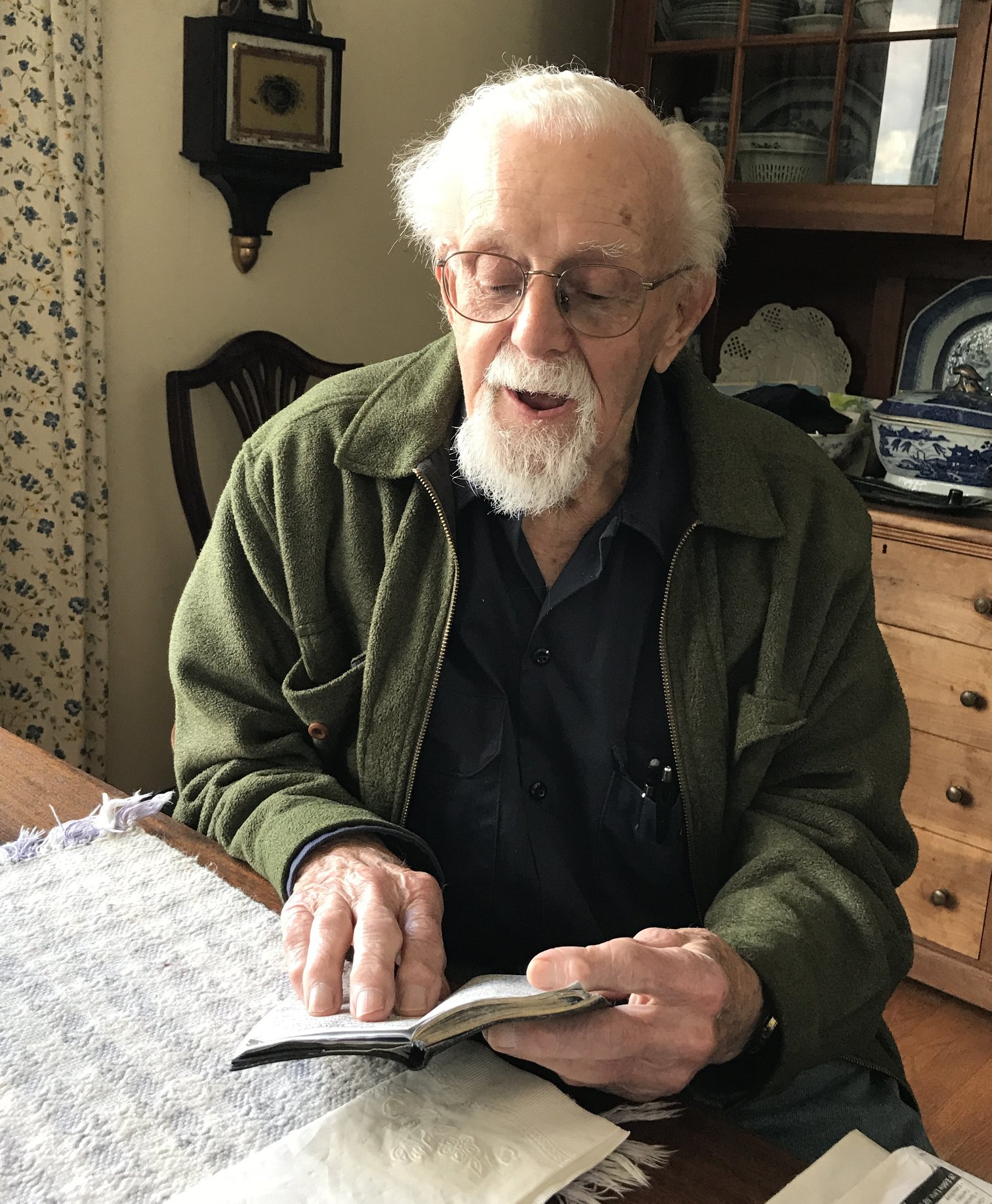

There aren’t many people around these days that can recall what it was like to live through World War II, either as civilians or as soldiers. Those that do, such as Brand Livingstone of Calais, are near-centenarians approaching their tenth decade of life. In that amount of time, some memories will undoubtedly fade, but, as Livingstone disclosed, some memories never lose their clarity.

Livingstone was born in Boston on December 12th, 1922. His family has long roots in the Calais area, and from his very first year he was brought to the Stone House on the St. Croix River to enjoy the summers. Over time and frequency of visitation, the Stone House has become an inseparable part of Livingstone, who now lives there year-round. “I’ve been here every year of my life except when I was fighting the Germans in Europe,” Livingstone expressed.

After growing up in Winchester, Massachusetts, Livingstone enrolled at Bard College in Poughkeepsie, New York. The war was already underway at that time, and while Livingstone was aware of it, it mostly seemed like a distant concept. “I didn’t know anything about war. I had never had any association with it,” he recalls. Despite the increasing disruption of the global war, Livingstone was intent on entertaining a young lady by the name of Mary Seeger. Seeger’s father was an officer in both World War I and II at the time, and her brother had already been called into service.

In December, Livingstone, too, was called for duty. “I was not a philosopher at that age. I didn’t question why, or who, but it was something I was attached to. As part of the bond with this country, you have to do what it says. And so, they drafted me in.”

Livingstone was taken with a large group of recruits to basic training in Texas. It was late winter and the weather was constantly cold and dusty with the wind blowing all the time. “We were always going down and getting our throats swabbed because they would get so clogged up,” Livingstone said. After basic training, some of the recruits were taken to the frontlines in Europe. In Livingstone’s case, he went through basic training three times before the military assigned him to the chemical warfare unit of the Air Force, which was part of the Army at the time. He was brought to Michigan and taught how to decontaminate planes that had been through mustard gas and exposure to similar toxins.

Prior to being deployed in Europe, Livingstone was given three weeks off. He spent it with Seeger, and within three days, the pair arranged to be married. They took a brief honeymoon at the Stone House for a week and a half before Livingstone went back into the Army. “They needed people bad. Nobody got excused unless they were dead or half-dead,” Livingstone recalls.

Livingstone was sent on a boat to England along with 8,000 other young men, he remembers. “They were a wild bunch of people,” he said of his fellow soldiers. “They spent money and energy as quickly as they got it. One of their favorite sports was hitting each other. They were taught how to be aggressive, and they were.”

For a time, Livingstone and his peers spent their days in uncertainty, waiting to learn who would be called to the front lines and when. The sense of nervousness pervaded the troops, many of whom engaged in wanton behavior as they bided their time. “I was in a unit that … was getting ready to go overseas, but we didn’t know when.

“All of the sudden, we knew when,” Livingstone said. He described how his unit was quickly organized to be deployed in France. He boarded a vessel, and on Day 9 of the Normandy beach invasion in June of 1944, he landed.

“There was all kinds of shooting going on,” Livingstone said. “Constant airplanes over head. It was really quite a wild time. Not as wild as it was five or six days earlier, but we hadn’t broken out at all. We had taken the lower part of the Cherbourg peninsula, but that’s it.”

Gradually, the Allied troops pushed the Germans back. “Finally, I knew when there was a big bombardment going on that all the sudden we had broken through the German lines,” Livingstone said. “We started their removal toward Paris and all the other places.” His unit went from town to town, airfield to airfield, preparing to decontaminate planes as needed. “Thank God, it was never required,” Livingstone said.

At one point, as he was moving through France, he took time to walk through the woods by a village. He came across an old training center with many of its signs still up, and explored around it in idle curiosity. Just over the edge of a hill, he spotted a sight that remains clear in his memory to this day – a rusted tank from World War I. “I thought to myself, ‘What the h— are we doing this for again?’ I can recall that thought so clearly, so distinctly.”

After the Germans retreated, the question for the U.S. troops was who would get to go home, and when. “But we finally realized that anyone who got to go home early would have to go to Japan. They still had a lot of boats, and they were still carrying on the fight. They were not going to surrender.” Livingstone was sent home to Utah to prepare for redeployment; however, before it happened, the U.S. dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, thereby ending the war.

Coming back to life as a civilian was not easy for Livingstone. He and his wife soon produced three children, and he desperately needed a job with steady income. Unfortunately, so did the other millions of returning soldiers, and times were frequently lean for the young couple.

With the passage of the G.I. Bill, Livingstone was able to return to college and receive a small stipend to live on. He would graduate with a degree in psychology, and later he would go into the field of paper and fiber, eventually becoming Vice President of Groveton Paper Mill in New Hampshire after working there for 25 years. Livingstone and his wife retired to Maine in the 1970s to rehabilitate the Stone House to a year-round residence.

Livingstone’s connections to major wars are significant, and, in fact, he remembers an anecdotal interaction with his grandfather, a Civil War veteran. At the age of 3, he was sitting at the Stone House watching his grandfather take giant puffs off his cigar. The young Livingstone indicated he wanted to try it, and his grandfather obliged him. He took in as much smoke as he could, just like he saw his grandfather do. “I took it to my toes,” Livingstone said mirthfully. “I thought I was going to die.” His grandfather would pass away two years later.

Asked if he felt another world war along the lines of what he had experienced was a possibility, Livingstone responded after a brief contemplation. “I don’t think we’re going to have another war. I don’t think people will be fooled to that extent again.” He said, however, that it is dependent on proper education. “We’re in a funny age, in some ways, thinking that guns solve all our problems. We’re not bringing up people from an early age to understand how you can live without going to war.”

These days, most of the time, Livingstone isn’t thinking about war. Instead, he spends his time engaged in tending to the Stone House, grooming its vegetable gardens and admiring the flowers his wife so passionately adored. He has never stopped being civically engaged or politically informed, however, and he wonders at the world that is being left for his descendants. “We’ve got to start with both the parents and the children, and educate them both,” he said. “Life can be good if you realize at an early age that you must save, you must spend, you must be careful – and you must be educated.”