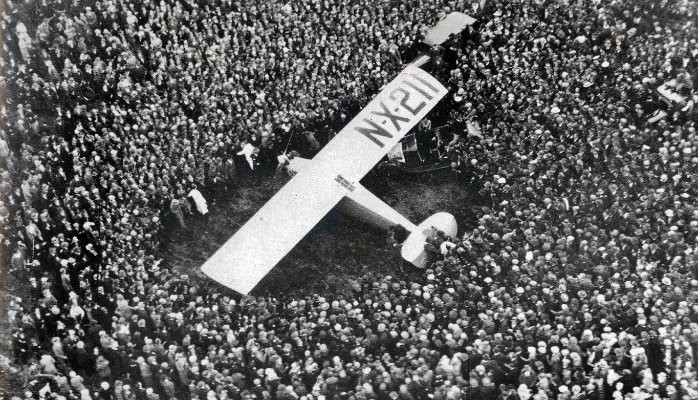

Lindbergh’s plane mobbed at airport in Paris after first transatlantic flight 1927

When Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris in 1927 after his historic first transatlantic flight, he was greeted by over a hundred thousand people at Le Bourget Aerodrome in Paris. They swarmed Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis; the gendarmes were barely able to contain the crowd. Tens of thousands of Parisians crowded the rooftops of nearly every building in the city to get a glimpse of the approaching plane and French flyers took to the sky to escort Lindbergh on the last leg of his remarkable flight. The flight inaugurated a new era, in just 33 hours and 30 minutes the world had gotten much smaller.

The Spirit of St. Louis was a top-of-the-line airplane for 1927, sturdy, beautifully engineered and specially designed for the transatlantic flight. Lindbergh was a courageous and accomplished flyer who knew he was risking his life the day his plane, overloaded with extra fuel, bounced down the runway of Roosevelt Field in New York. After his safe arrival in Paris there was some suggestion that Lindbergh would fly the Spirit of St. Louis home but this plan was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge who was afraid his now famous pilot would not make it home and Coolidge had good cause to worry; the flight across the Atlantic from east to west was a far more hazardous flight than from west to east. A plane had to contend with strong westerly winds which made the flight both more dangerous and the equivalent of over 800 miles longer.

“The Greatest Solo Fight ” ever ended in a Pennfield N.B. blueberry field

You are probably wondering at this point what Lindbergh’s historic flight has to do with local history. I could claim without too much of a stretch that The Spirit of St. Louis flew over this area on its way to Paris and that would be only a slight exaggeration. Lindbergh passed over the Bay of Fundy and was quite close to our coast at a very low altitude so the odd Downeast fisherman may have glimpsed an unusual object in the sky but in truth the Downeast connection to Lindbergh’s flight is indirect but still pretty interesting. Many claim another solo transatlantic flight was more daring than Lindbergh’s and it came to an unexpected end in a local blueberry field.

James Mollison after landing in Pennfield

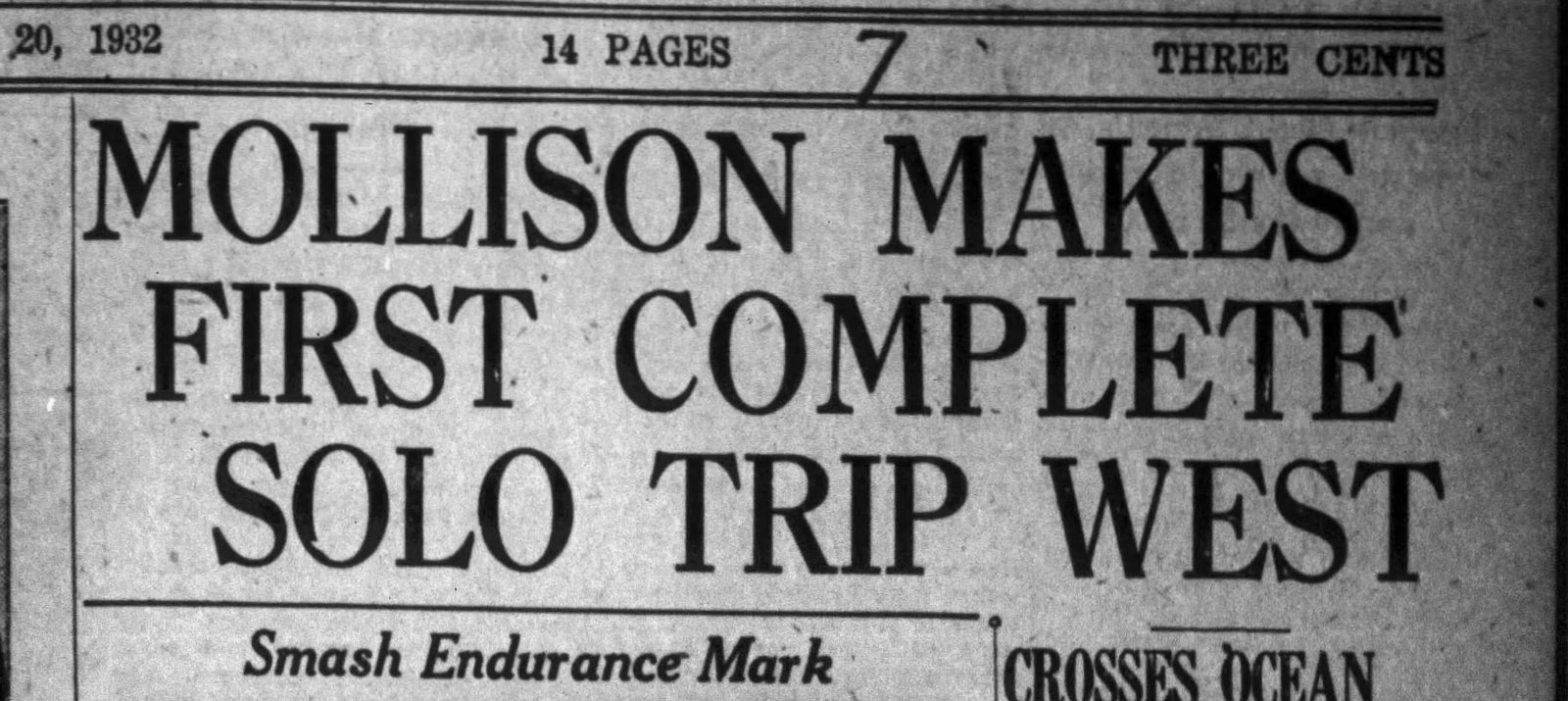

Bangor Daily News August 20, 1932

It was not until 1932 that a solo east-west flight was successfully made, and the plane landed not to adoring crowds of tens of thousands and the blinding light of a thousand flashbulbs but unexpectedly in a Pennfield N.B. blueberry field which according to Google is within 20 miles as the crow flies of most reading this email. The pilot, Mollison could have just as easily continued for a few more miles and landed in St. Stephen, Calais or any number of blueberry fields in Meddybemps.

Even though he had failed to reach his New York destination, some aviation historians claim his flight was the “Greatest Solo Flight Ever Made.” Still, the pilot, James Mollison, was unhappy and very tired. According to the St Croix Courier of August 25, 1932:

“Heart’s Content” lands at Pennfield after cross-Atlantic flight

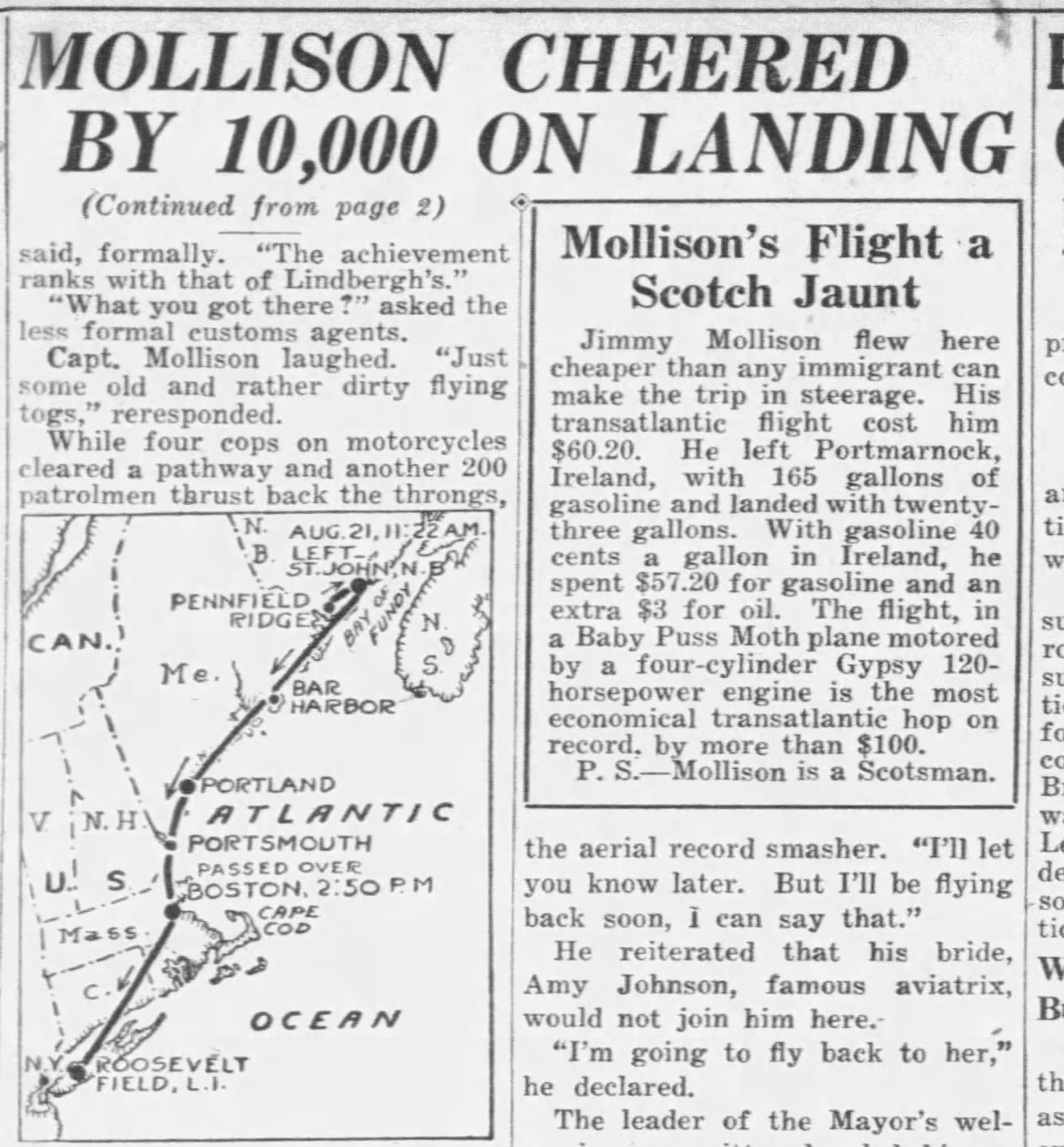

Captain J.A. Mollison’s tiny Puss Moth plane, “The Heart’s Content,” rested in James Armstrong’s field at Pennfield Ridge, nine miles from St. George, last Friday afternoon following the completion of the first solo flight westward over the Atlantic. The landing in Charlotte County was made at 12:50 A.S.T., just 30 hours and 15 minutes after the plane left Portmarnock, Ireland. The machine was taxied into this position after the landing to protect it from the driving rain which swept intermittently across the field that afternoon. The plane has a 120-horsepower motor and on leaving Ireland carried 170 gallons of gasoline, of which only 23 were left when it landed at Pennfield. “I had rotten luck,” Captain Mollison commented ruefully, “Ten more gallons would have put me in New York non-stop!’

“I went along the coast and then well my gas supply was so low I knew I couldn’t make my destination” Mollison told the St. John Evening Times Globe reporters who rushed to Penfield, about 70 kilometres southwest of Saint John after he landed. “And I was all in, tired as a dog and when I saw this field I decided to put down.” The field belonged to farmer James Armstrong and the plane had come to rest in the middle of a patch of blueberries.

As the Times Globe said on August 20, 1932, the day after Mollison landed, Pennfield had “suddenly and unexpectedly become the center of the limelight of World News.”

The Boston Globe reported on the flight on August 19th:

FIRST SOLO HOP EAST TO WEST OVER NO. ATLANTIC NEW YORK, Aug 19

J. A. Mollison, who landed his plane, The Hearts Content, at Pennfield Ridge, N B, today, after a flight from Portmarnock. Ire, is the fourth aviator to achieve a non-stop westward crossing of the North Atlantic Ocean and the first ever to make the flight alone. Only two other North Atlantic solo flights have been made, both eastward. They were by Col Charles A. Lindbergh, New York to Paris in 1927, and Amelia Earhart, Harbor Grace, N F, to Ireland this year. The westward flight is considered to be, in effect, 800 miles longer than the eastward hop because of prevailing winds.

Even more remarkable was his plane, a de Haviland Puss Moth. The Moth was a light plane made for the commercial market, not specially designed as was the Spirit of St. Louis for a transatlantic flight. It was nothing but a “flying gas tank” according to one expert and “as basic as you could get in 1932.” Mollison told reporters from St. John he brought only “a handful of barley candy and two miniature bottles of brandy” along as sustenance. This may not have been entirely true as he later admitted he never flew without a sufficient supply of brandy to get him to his destination-a habit which was to create problems for him throughout his life. He had ditched his radio to save weight but later admitted this was a mistake.

New York Daily News August 22 1932

The next day Mollison flew to St. John, refueled and completed his flight to New York. It was a remarkable achievement and Mollison, although already acknowledged as one of the most accomplished and daring flyers of early aviation, entered the rarified heights occupied by such aviators as Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh.

The Mollisons on the right quickly became celebrities, vacationing here with Amelia Earhart and her husband

Mollison had married Amy Johnson, the Amelia Earhart of European flyers, only a few weeks before the flight. She was considered the better aviator of the pair and the two later flew together across the Atlantic where it is said not a civil word was exchanged between them during the entire trip and very few afterwards. Dubbed by the press the “Flying Sweethearts” the marriage lasted only a couple of years. The problem in the marriage as reported in one newspaper was Mollison’s penchant for “elbow bending.” Amy Johnson Mollison was killed during World War 2 flying for the RAF. He remarried a couple of times, but his nemesis alcohol put paid to all of his relationships.

According to a CBC special Mollison’s pilot license was revoked in 1953 and in the late 50’s he ran a bar where he may well have been the business’ best customer. He was confined for a period to a mental hospital from the effects of alcohol abuse. His last wife commenting on his death said- “It was the drink that killed him.”

James Mollison Obituary London Daily Telegraph November 2, 1959

Mr. JAMES A MOLLISON RECORD-BREAKING FLIER OF THE 30s

DAILY TELEGRAPH REPORTER LONDON

MR JAMES ALLAN MOLLISON who achieved fame by his remarkable series of flying exploits between 1931 and 1936 has died aged 54. In those five years he became the first man to fly solo across the North Atlantic and back and the first to make a westward solo flight across the South Atlantic. In addition, he accomplished record-breaking flights between Britain South Africa, Australia and India

His journeys were all the more noteworthy because they were in light planes of the “Moth” type. His first wife was Miss Amy Johnson whose own achievements in the air at that period had evoked great national enthusiasm. In 1933 they flew together on a non-stop flight to New York.

Jim Mollison was a Scotsman of slight stature and boundless courage who joined the RAF with a short service commission in 1923. Six years later he went to Australia and after being an instructor became a pilot of the Australian National Airways. Eager to take advantage of the great skill he had acquired both as a pilot and navigator, he set off for England in July 1931 in a tiny “Moth” with an open cockpit. He showed astonishing powers of endurance in covering the 10000 miles in eight days 21 hours 23 HOURS WITHOUT REST. He allowed himself only two hours’ sleep each night and for three days had to fly without goggles. They had blown off when he was over India When he reached Croydon on the last day after a spell of nearly 23 hours without rest, he had red-rimmed eyes, was almost asleep and was deafened by engine noise. He had to be lifted from the machine completely exhausted.

Six months later he flew from England to the Cape in four days 1hr 19min. He was so worn out with fatigue that he had to land on a beach and when found sitting in the cockpit was at first thought dead. Suffering from lack of sleep and eyestrain, he had for two days seen all his instruments in duplicate. His other long flights across the North and South Atlantic and to Commonwealth countries were all marked by his wonderful display of stamina The last was from Newfoundland to Croydon in 1936.

HAPPY-GO-LUCKY PILOT

Mollison, despite his great achievements and his exceptional skill, was a popular happy-go-lucky pilot. He confessed that he had no belief in physical training for his tasks “I am much braver” he said, “when I have a little liquor inside me-always like a good party before starting.” It was perhaps characteristic of his attitude that on one of his flights across the Atlantic he wore a dinner jacket because he had not left himself enough time to change. On another occasion he made a long-distance flight in carpet slippers. Usually, he carried a bottle of brandy for as he remarked “You can’t be too careful on these long flights.”

His hope 20 years ago was that one day he would be the first man to fly round the ‘Equator. In the 1939-45 war he flew in Air Transport Auxiliary delivering all types of war planes. Amy Johnson served in the same capacity, losing her life while flying over the Thames Estuary in 1941. They married in 1932 and she obtained a divorce in 1938. Mollison married again in the same year but obtained a divorce in 1948. In the following year he married Mrs. Maria Clasina Eva Kamphuis who survives him.

Pennfield airmen World War Two

As to Pennfield, the town had blueberries to harvest and little time for reflection on the historic event which had taken place on James Armstrong’s blueberry field. Founded in the 1780s by Quakers from the United States, Pennfield’s historical website does mention the event but only briefly, devoting only a couple of sentences to Mollison’s landing. The site does have some nice photos of Mollison and his plane. This is somewhat odd as the most notable era in Pennfield history was World War Two when Pennfield was the site of one the largest military airfields in Canada. Aviation history had been made in Pennfield only a decade earlier. During the war, hundreds of Canadian airmen spent their leave and weekends in Calais and St. Stephen where they befriended and sometimes clashed with the hundreds of Seabees then training in Quoddy Village.

The parish made no attempt to monetize its sudden fame by reenacting the famous landing every August complete with a carnival, palm readers, daredevil pilots, wing walkers and perhaps even the annual appearance of James Mollison. Some communities would have jumped at the chance, and I suspect James Mollison would have been game.