In the early days on the St Croix Valley the life of a laborer, even those with some specialized skills or engaged in dangerous work, while not quite to coin a famous phrase “ brutish, nasty and short.” was very, very hard. Workers had little leverage with their employer whether in the lumber mills, woods or factories. The terms and conditions of employment were whatever the “barons” decided was best for their bottom line. Wages were paid “per day” and the length of the workday was set by management. In many cases, such as the Chase mills in Baring, the meager wages of the worker were partly paid in “cram”, credits at the company store. Baring’s company store is shown above. Here workers paid inflated prices for low quality goods and often spoiled food and were usually several month’s wages in debt to the company.

Occasionally conditions became intolerable and the workers desperate enough to strike and possibly lose their jobs. One such instance was a Saturday afternoon in July of 1903, when the foreman of the Eaton lumber dock at the bottom of Calais Avenue announced there would be no work that afternoon. The men of the “boom crew” did not welcome this unexpected holiday. They needed to work a full week at $1.50 a day just to survive. Times were hard and the men had many grievances. They decided to strike. According to their spokesman “They have knocked us off, and now when they want us again they will have to pay us $1.75 or we don’t go back.” The Advertiser wrote “When the news of the strike spread through the village like wildfire, people stood aghast. Nothing like it had ever been heard of, let alone attempted in the community. Old men shook their heads, and old women wrung their hands and said, mercy on us, what will be the result.”

The results was, not surprisingly, that scabs were brought in to do the work of the boom crews. Sunday and Monday passed quietly, the strikers were orderly although the Advertiser noted a “glint of determination” in their eyes. On Tuesday one of the scabs, Shudie Dow, fell in the river. According to the Advertiser “When the alarm was given the community breathed a sigh of satisfaction and hoped Shudie would be drowned. But he wasn’t. Someone got him by the hair and yanked him out and spread him on the platform to dry. Even then there was a hope he was dead, but it was a vain hope.” By Tuesday afternoon the strikers had turned more militant. Believing their original demand of $1.75 to have been too modest, they raised the stakes to $2.25 per day. Upon hearing this news Frank Todd, manager of the company, conceded the strikers had point about present wages being unfair, to the company. Henceforth he announced, daily wages would be $1.10 and, if the workers didn’t get back to work the next morning, he “would give them something they wouldn’t like.”

The threat “struck consternation” among the strikers and on Wednesday morning the Advertiser reported “they all made such a race for the boom that they couldn’t stop when they got there but plunged right over it into the water.” The Advertiser clearly felt a little more backbone was needed in the workers ranks. Because the strike had ended in such an ignominious fashion, the Advertiser predicted nothing again of its kind will ever again be attempted in Calais.

The Advertiser was wrong when it said nothing like this strike had ever been heard of before in the St. Croix Valley. There had been many strikes over the years. Just 13 years earlier Eaton’s workers struck and forced an increase in the daily wage but this was a rarity. Success in 1890 was due to public pressure and financial support for the workers which allowed them to hold out longer than usual. It was said to have been the first successful strike against the lumber barons in the St. Croix Valley but as the 1903 strike shows Eaton soon regained the whip hand.

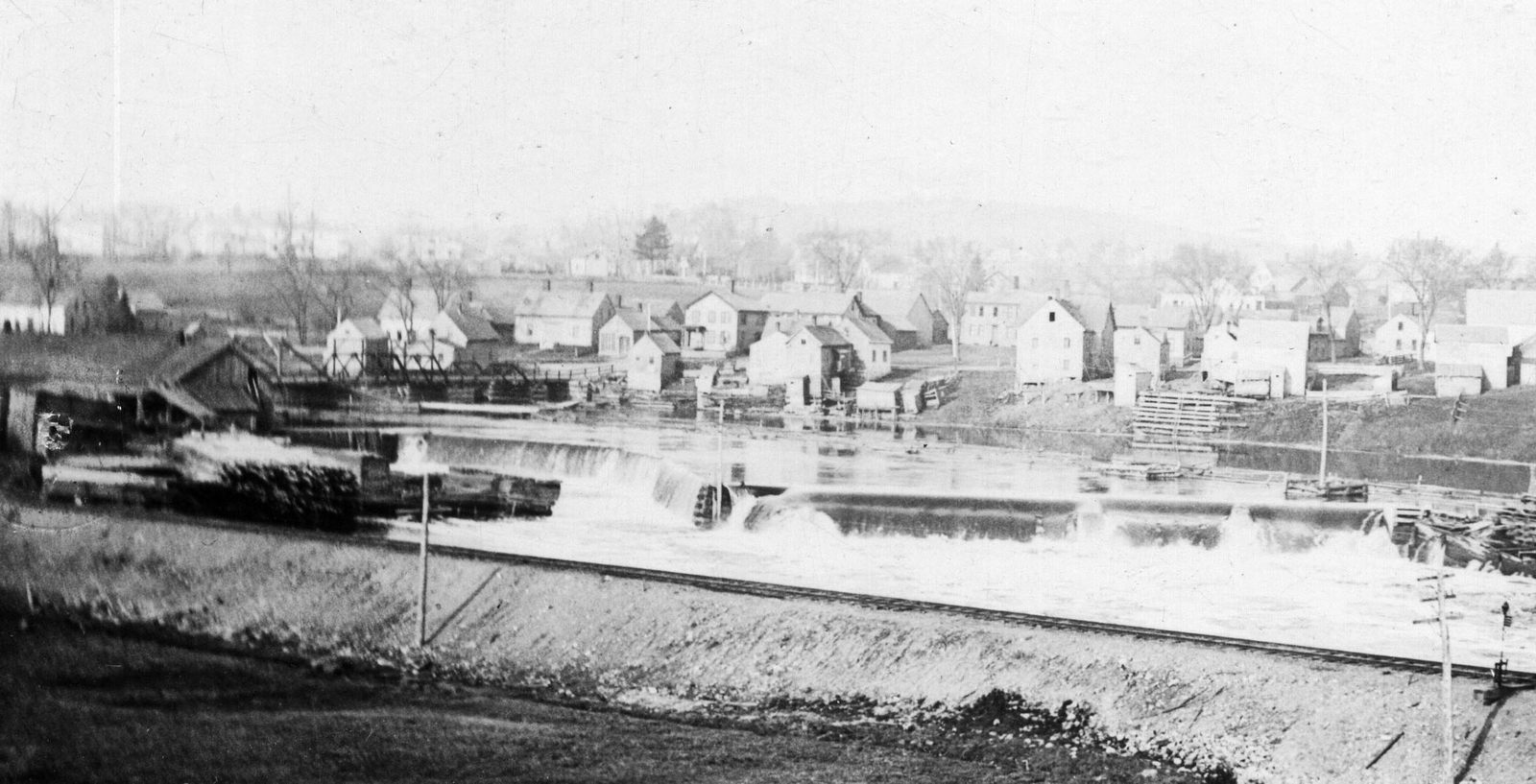

As early as 1851 the Calais Frontier Journal reported a formidable movement among the workers at the mills on Middle Landing, Union Street pictured above. The Union Street Bridge was located here until it washed out in the 1960s.

The Millmen at the Union Mills on both sides of the river have ‘struck’ for the ten hour system and higher wages. The shipwrights in the employ of James S. Hall & Co. have laid down their tools determined not to work more than ten hours a day. Whether this course will have the desired effect remains to be seen. Ten hours a day is enough, in our opinion, and in the opinion of all who are not particularly interested in the manufacture of lumber for any man to work, provided he works ‘man fashion’ as old Sim says. But there is another motive at the bottom of this movement which casts the ‘ten hour system’ into the shade. The California fever has recently received an impetus owing to flattering accounts received from the gold regions. Men who left this village two years ago in comparatively poor circumstances have returned with their ‘pile.’ The reports of gold being found within the confines of Maine has been another incentive to this movement. Waggon loads of men are leaving this section almost every day for these ‘new diggings’ and the fever has only commenced. But the great trouble, after all, arises from the treatment of the millmen receive from the mill owners.—The fellers of the forest, the river drivers, the real bone and brawn, the thews and sinews of the country, are considered by the mill lords as mere ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ and are treated as such. If these men received a fair remuneration for their labor this strike would not have occurred. It is not so much the number of hours they work as the manner in which they are paid that makes them dissatisfied. Their wages appear large enough on paper, but when sifted down to dollars and cents, cash, they receive but a small pittance for their long days sweat and toil— some, one half of what they really ought to receive and the remainder not more than two thirds. The contemptible system of ‘Cram Trade’ is the great grievance of which they complain.— We have been told that there is not a river in Maine on which lumber is manufactured where men are so badly paid as on the Schoodiac.

To the mill owners of Schoodiac we would say, give your mill- men fair wages—pay them what you agree to, and don’t take fifty and a hundred per cent from their hard earnings in your cram dealing. Treat them as men possessed of feelings and aspirations of all through whose veins flow the blood of free men and not as slaves and no fear but they will be contented and eschew strikes of all kinds. Pay them their cash, and they will doubly repay you in hard bone labor by which means you get your cash.

We do not wish to be understood as advocating ‘strikes’ of this character; they frequently lead to bad results; but there are causes where forbearance ceases to be a virtue, and the occasion of the strike by the millmen is one of them

Had it not been for the exodus of men to the California gold fields it is unlikely the Union Mills workers would have risked a strike. There is no evidence the lumber barons met their demands for, as noted above, the first successful strike was reported to have occurred in 1890.

There were strikes against the lumber barons again in 1860 when the workday was 15 hours. The Calais Advertiser, which was very sympathetic to the strikers, reported a strike on the St. Stephen side:

“The laborers in the saw mills on the St. Stephen side were on strike last Tuesday for eleven hours and a half time, instead of 15 hours. All the mills are shut down. We have not heard the result but presume that, as in all such strikes, labor will have to succumb to capital. But eleven hours labor, in a saw mill, one would suppose is as much as any reasonable mill owner could, in good conscience, exact of men. But there are many on the river, we are sorry to believe, who would not be sorry if men should labor twenty hours a day. Men who coin the muscle and blood of fellow men into dollars and cents to fill their coffers with filthy lucre. We hope laborers may succeed in wringing the poor boon of a few hours less labor from their employers”

The lumber barons were not the only employers who had to deal with labor disputes- workers in the shoe factories, Woodland paper mill, the Red Beach Granite and Plaster Mills and the Cotton Mill all struck over the years. After 1900 workers began unionizing and formal settlement procedures were instituted. Strikes were often settled without shutting down the mills and factories but not always. However before unions it seemed the only way to get the attention of the owners was to strike and shut down the factory or the mill.

In 1890 workers at the St Croix Shoe Company at the bottom of Barker Street in Calais walked out when the owners demanded they do extra work for no additional pay. The strikers demanded a raise of 1 cent per pair of shoes made. After being on strike for week the workers suggested a compromise of half a cent per pair of shoes and were told their places had been filled and their services no longer required. Such was the danger workers faced in striking in those early years.

Workers at the plaster mill in Red Beach struck in 1903 and surprisingly had some limited success. The strike was led by the “lime” workers who received a 25 cent per day raise and a shorter work day of 9 hours. Workers who were already making over $1.25 a day got a 10% raise. However by 1906 when the workers struck again for better working conditions the company refused to negotiate and strikers returned to work after 6 weeks without a raise or shorter workday.

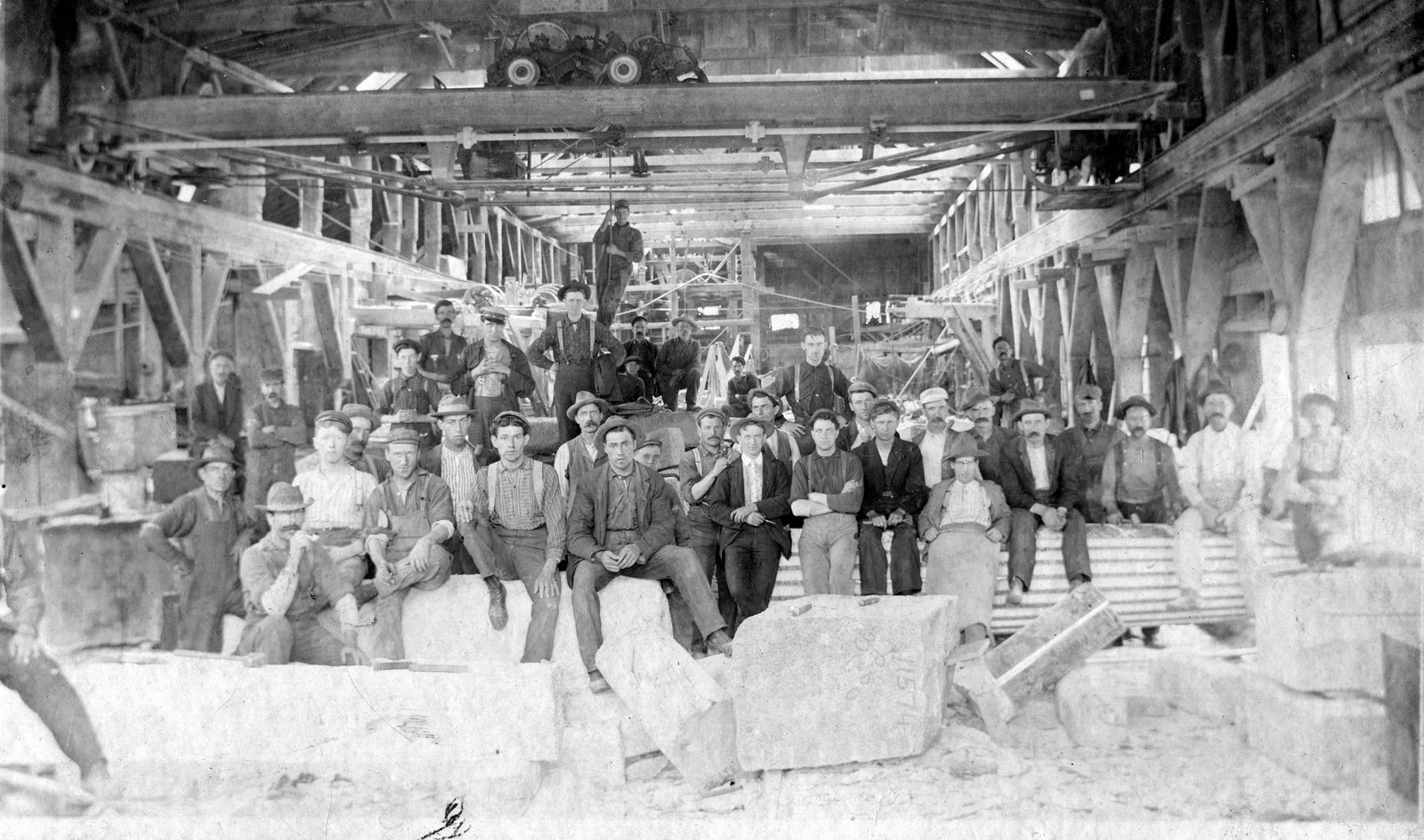

In 1908 the workers in the polishing shed of the Red Beach Granite Works struck and after three weeks the owners agreed to increase their wages from $1.75 for a 9 hour day to $1.88 for an 8 hour day. The men, who by this time were becoming desperate, were inclined to take the offer but the union refused to countenance such a meager increase, demanding $2.25 a day. We have no information on how this strike was settled but it is the first mention in any report of the involvement of a union. The labor/management landscape was changing and with the introduction of laws to protect worker’s rights, the field began to level and the workers acquired more bargaining power.

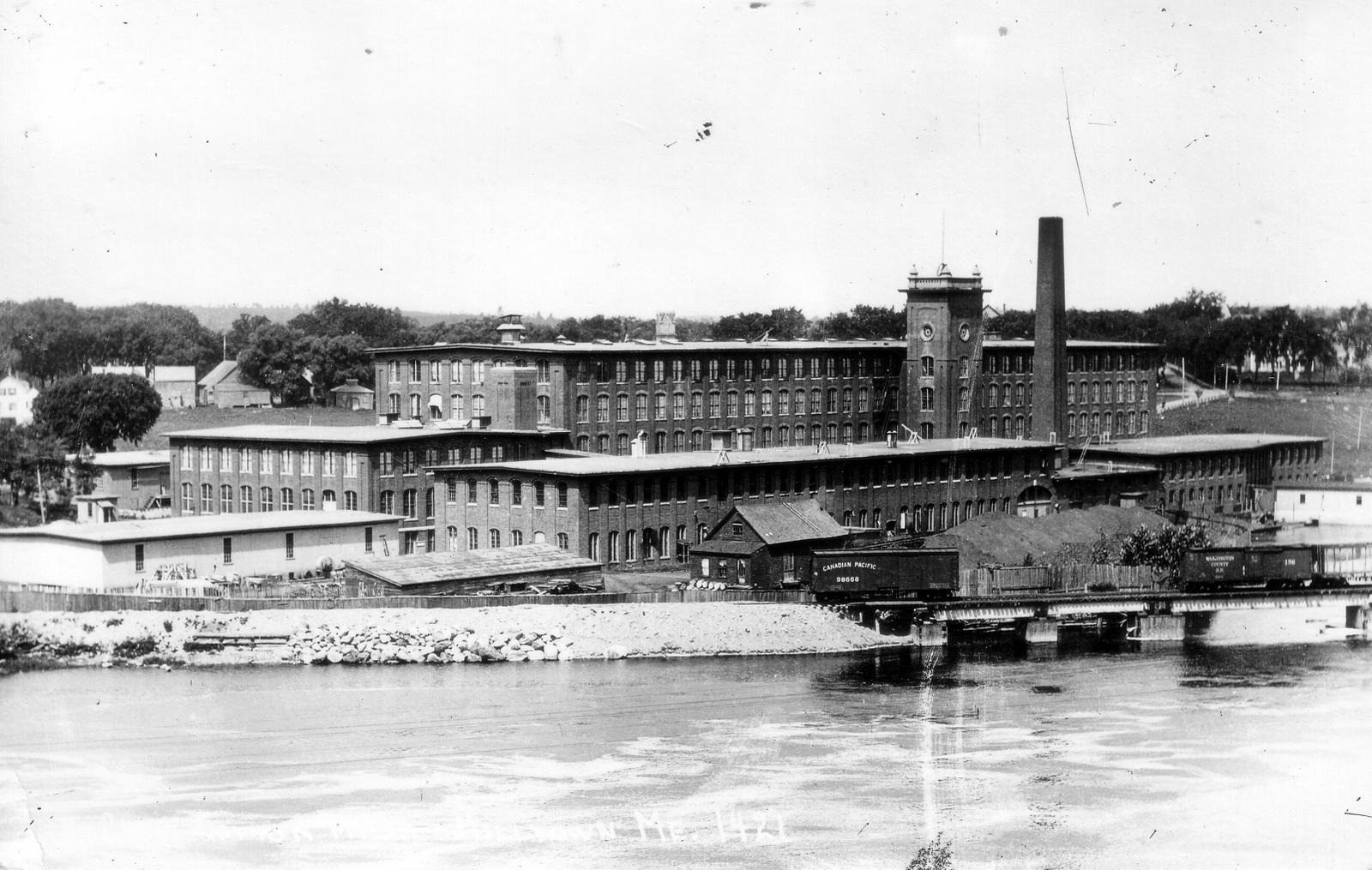

The Cotton Mill in Milltown NB employed hundreds of workers from both sides of the border. The history of strikes there, as at the paper mill in Woodland, is very lengthy. Woodland began a union town very early on and while the unions did go on strike occasionally to exact wage and other benefits from the company in the end the mills made a reasonable profit, often kept good workers for a lifetime and the workers enhanced their economic status. The Cotton Mill sometimes faced difficult economic conditions and in many years was only marginally profitable. Workers were sometimes asked to take cuts in pay or face decreased workweeks because of a lack of demand for the mill’s products. This led to some labor strife especially in the early years. When the mill was forced to close in 1957 not a few workers placed some of the blame on the union, complaining they were not willing to make enough concessions to management to keep the mill open. In fact by 1957, even had the union made substantial concessions, the Milltown Cotton Mill was no longer able to compete in the global market. Workers interviewed for Bill Eagan’s history of the Cotton Mill generally agreed the union had accomplished a good deal for the workers over the years.

Finally we want to mention one last strike which ended well. The photo above shows the A and P Supermarket on Main Street being built for the Unobskey’s in 1940. The local carpenters on the job struck for higher wages and the engineer in charge of the project wired to Boston for a crew of 12 carpenters. When Arthur and Charlie Unobskey learned of this they not only protested but convinced the engineer to pay the locals union wages, at that time 75 cents an hour. The job got done and within just a few months Calais’ first “Supermarket” opened for business.