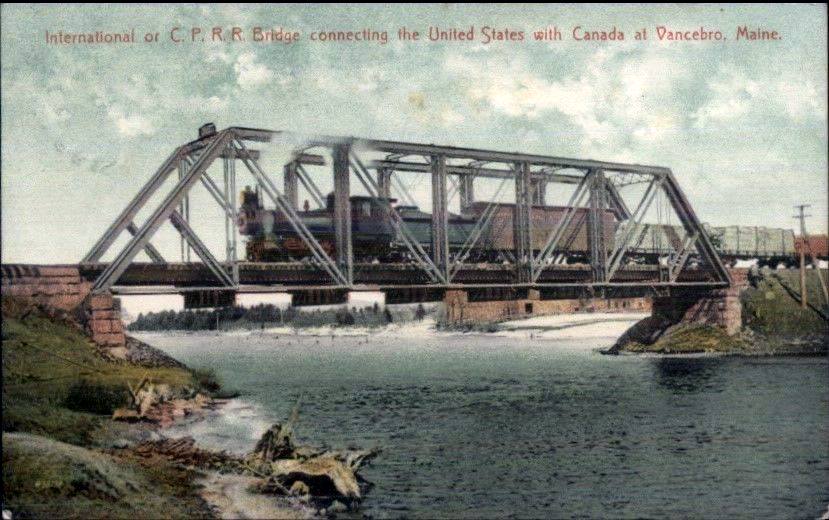

The Vanceboro Bridge

The photo above shows the railroad bridge between Vanceboro Maine and McAdam NB. It gained fame in World War One when a German saboteur, Werner Van Horn, attempted to blow it up to prevent supplies reaching Europe from the U.S. through the ports of St. John and Halifax. In 1899 a less dramatic event occurred involving the bridge when, it is assumed, a new mother traveling on the train sewed her just born infant daughter into a pillowcase and threw the body into the river as the train crossed the bridge. We say assumed because there is no proof this is what happened, but it is the most likely explanation of the event. The body was discovered by local rivermen working to break a logjam a few miles downriver.

Serious logjam on the St. Croix

From Bangor Daily article of May 31, 1954, 55 years after the baby’s death

“The men were picking at the jam with their peaveys and pick poles when all of a sudden Jack O’Malley of Vanceboro let a yell out of him that stopped the men in their tracks. At the moment O’Malley was walking the logs near a wing which had caused the logs to back up for half a mile. He pulled his peavey up from between a couple of logs and there hooked on to it was a pillowcase which had been sewed up at the open end. The peavey had ripped the cloth and there inside the case the men could see the body of a newborn infant girl.”

According to Ada Pine of Vanceboro, a relative of some of the crew breaking the logjam, the account is somewhat incomplete. The contents of the pillowcase were not immediately apparent and assuming the pillowcase was just a sack containing “Vanceboro cats” O’Malley was told there was work to do and he should throw the pillowcase back into the river. The pillowcase had, however, already revealed its secret to O’Malley and the men were confronted with a dilemma. Many miles from civilization and tasked with freeing the logjam the men brought the infant’s body to the American side and with prayers and not a few tears buried the infant in a shallow grave. They broke the logjam and moved downriver.

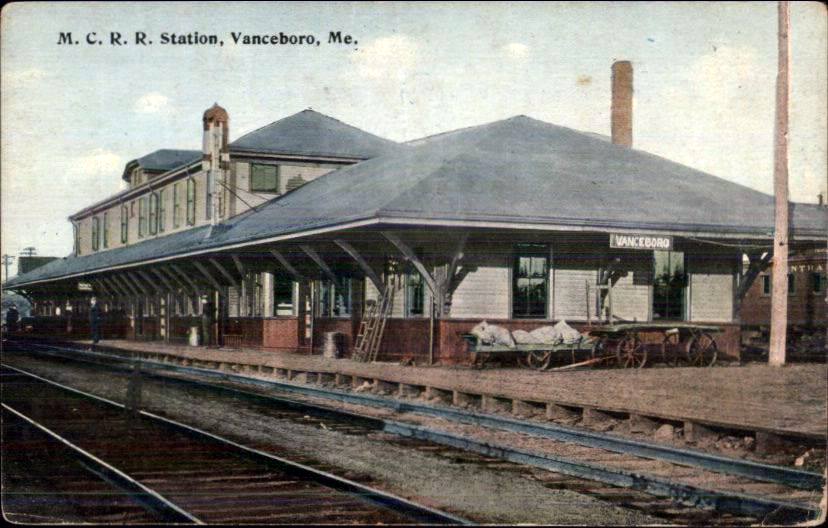

Demolished in the 1960s

As far as we know there was no investigation into the baby’s death. The assumption the baby had been thrown from a train crossing the bridge was the most likely explanation and as Ada Pine of Vanceboro pointed out in Bangor Daily News articles written in the 1960’s there was no law enforcement agency in Vanceboro in 1899 capable of conducting an investigation. The likelihood of discovering the identity of the mother, if indeed the assumption was correct, was nil. I recently discussed the case with Holly Beers of Vanceboro, 95 years of age, still spry and Vanceboro’s resident historian. He knew some of the men on the drive and had himself, as a teenager, worked on the river. Holly says in 1899 the Vanceboro station was a very busy place. Trains left the station every 15 minutes day and night, the restaurant in the station was open 24 hours a day and the 15 rooms in the station hotel were usually full. Hundreds if not thousands of people passed through Vanceboro daily and any of them could have been responsible for the baby’s fate.

This is not to say there were no law enforcement officers in Vanceboro in 1899. Dozens of customs officers enforced rather obscure customs regulations much to the annoyance of locals and travelers alike. For instance, there was a prohibition on the importation of seal skin garments into the United States. A New Brunswick woman wearing a sealskin coat caught the attention of sharp-eyed customs officers but when the officers attempted to seize the coat her husband grabbed it and a wild chase ensued through the rail yard. The New Brunswick newspapers were outraged. Local game wardens did manage to apprehend George Clinton of Prentiss, the “King of Poachers”, but neither the wardens nor the customs officers were equipped to investigate the baby’s death. While the “sealskin coat” incident got lots of press, the baby’s death was not even reported in the newspapers. It was only in 1954 that the story was told.

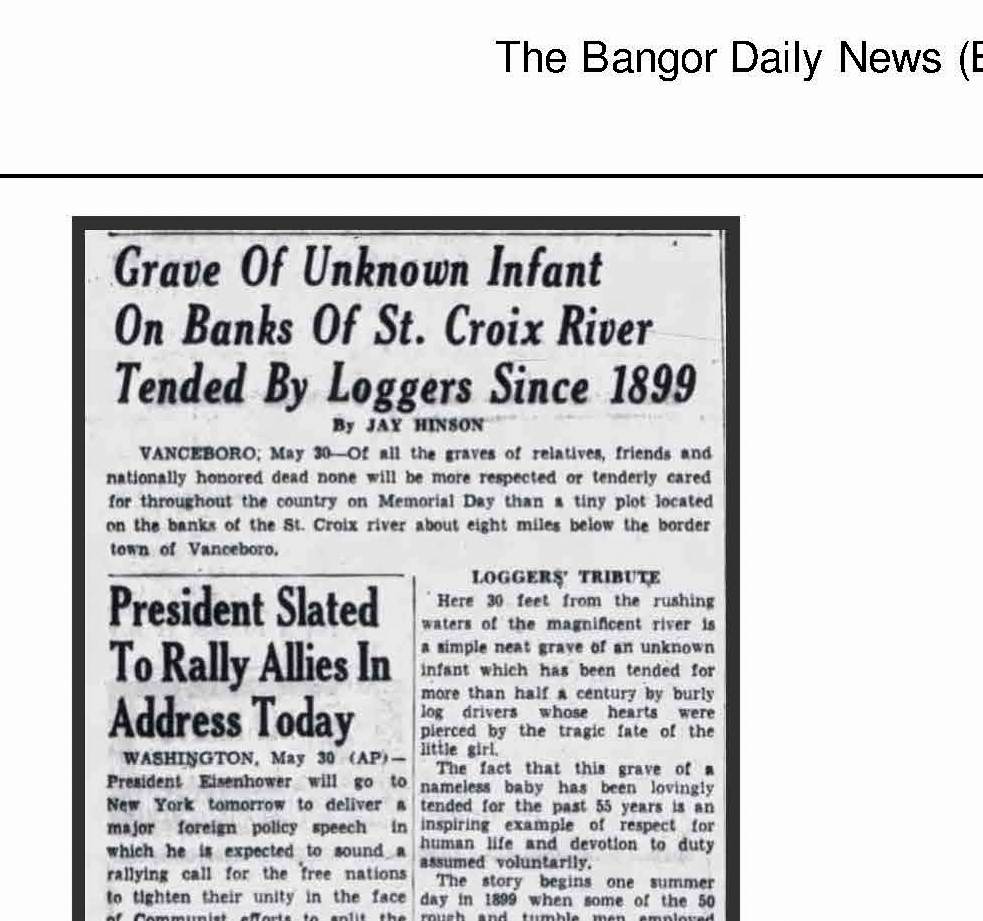

The first article to appear in newspapers regarding the infant’s death 55 years after the event

The baby, however, was not forgotten. The simple although emotional burial at Duck Point in 1899 was the beginning of a touching and heartwarming story of the loggers and river drivers from Vanceboro and now others who have tended the grave of the anonymous infant for over 120 years. It was first reported in the Bangor Daily News in May of 1954. Written by Jay Hinson, it was reprinted in the Calais Advertiser in 1961.

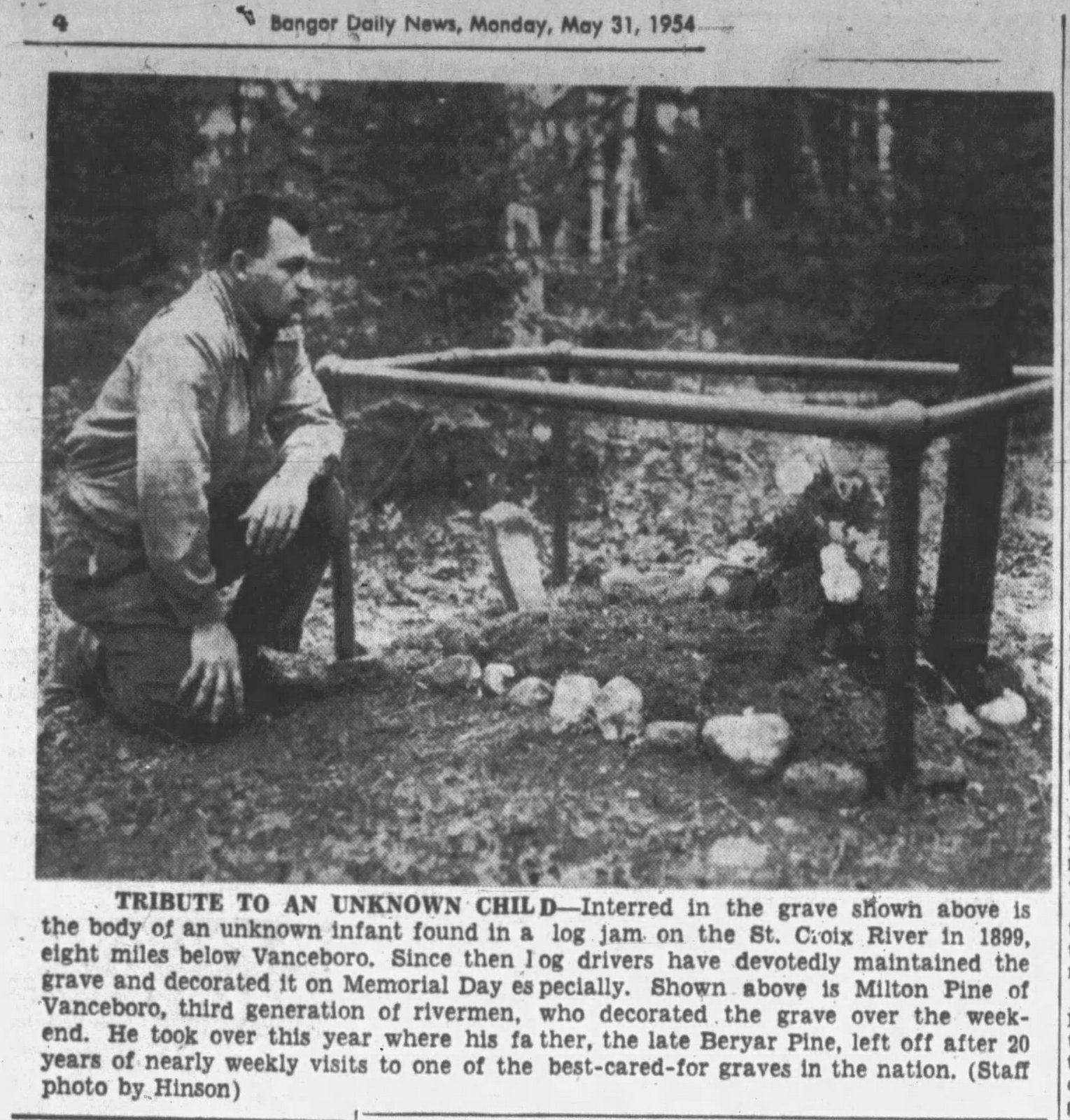

Milton Pine at gravesite

“Here 30 feet from the rushing water of the magnificent river is a simple neat grave of an unknown infant which has been tended for more than half a century by burly log drivers whose hearts were pierced by the tragic fate of the little girl.

The fact that this grave of a nameless baby has been lovingly tended for the past 55 years is an inspiring example of respect for human life and devotion to duty assumed voluntarily.

The story begins one summer day in 1899 when some of the 50 rough and tumble men employed on a long log drive by the outfit known then as the St. Croix Pulp and Paper Company went to work breaking up a jam at a crook in the river called Duck Point.

The men were picking at the jam with their peaveys and pick poles when all of a sudden Jack O’Malley of Vanceboro let a yell out of him that stopped the men in their tracks. At the moment O’Malley was walking the logs near a wing which had caused the churning trees to back up for half a mile. He pulled his peavey up from between a couple of logs and there hooked on to it was a pillowcase which had been sewed up at the open end. The peavey had ripped the cloth and there inside the case the men could see the body of a newborn infant girl.

At that time and in that section of Maine, which is remote even today, there was no such thing as law enforcement; officials such as coroners, medical examiners or county attorneys had never been heard of. The awed men merely walked to shore on the American side of the river, cleared out a spot and buried the child.

There was of course much speculation as to where the infant’s body came from. Through the years it has become the general belief that the pillowcase holding the baby was tossed from a train passing over the river on the bridge between Vanceboro and McAdam N.B.

Because they were engaged in bringing up the rear of the drive the men had no time to waste but the following spring three men who were tending out at Duck Point as the forward crew erected a marker.

On the polished thick piece of slate which was roughly the shape of an elongated triangle Horace Keene inscribed in graceful script with the point of his knife the following brief epitaph: “A child found in the river and buried here. June 29, 1899.”

On the side of the headstone Keene etched these words: “Fri 4 1900 graded and seeded and placed by Horace Keene, Sandy McGraw and Roy Middlemiss.” This last undoubtedly referred to the fact that the three men had on a certain Friday in the spring of 1900, smoothed over the grave, planted grass on the plot and placed the headstone.

Continued Care

Horace Keene, who had been a log driver since about 1875 continued to be on the forward crew at Duck Point each summer for two months until the early 1930’s when he died. But each year he took care of the baby’s grave. Each year, too, as long as the log drive continued the other drivers would stop by for a moment to take a look at the resting place of the most famous child on the river.

When Keene died it looked as though that was going to be the end of it. Most of the old-timers who were associated intimately with the event had expired by 1934. However, a man named Beryar Pine employed by the railroad at Vanceboro, decided to take over the care of the scenic little plot. Pine, who was born at famed Loon Bay further down the St. Croix River, had heard his father, Steve Pine, a river man on that drive in 1899, retell the story so many times he felt a part of it.

And so, until Beryar Pine’s death eight years ago, at the age of 63, the grave at Duck Point was meticulously cared for. Pine, who evidently delighted in tending the spot, would take his canoe Saturdays and drift downriver eight miles to the point where he would fix up the stones around the plot, put fresh moss on top and perhaps pick a few river lilies to place at the headstone. He replaced a cedar fence Keene had made with a more lasting metal one. And he tediously carved a new marker out of a piece of cedar when he noticed that the inscriptions made by Keene on the slate rock were becoming illegible.

The one day each year that the unknown infant’s grave would definitely be visited by Pine was Memorial Day. Pine would spend part of the holiday with his family and then, gathering some special garden flowers or a wreath, he would go visit the spot downriver.

With Beryar Pine dead, folks along the river expected that this would be the end of a beautiful example of remembrance. However, Milton Pine of Vanceboro, Beryar’s son, decided to keep the tradition intact, and a bouquet of flowers placed by the third generation of river men is decorating the headstone for the 62nd consecutive year. A railroad man like his father before him, Milton has a family of his own and it was of them he was thinking when walking away from the grave after decorating it he once said I suppose my oldest boy, if he stays in these parts and if he’s a mind to, will take over with the baby’s grave where I leave off.”

Ada Pine, her family and many others from Vanceboro and St. Croix have over the years made a point to visit and tend the grave. Writing for the Bangor Daily in the 1960’s Ada Pine of Vanceboro recounts gathering flowers with others in Vanceboro to put on the grave and in two articles written on July of 1967 gives her account of this story:

Bangor Daily News July 8, 1967, Ada Pine

POIGNANT SPOT

One of the poignant spots in Eastern Maine and one that never falls to arouse the curiosity of passersby is the grave of the unknown baby on the bank of the St. Croix River in Washington County. Mrs. Ada Pine of South Lincoln visited the grave often with her husband and sportsmen they guided on river trips, and it is a story that folks often ask her to retell.

For regular readers and summer visitors who would find the spot most interesting, Mrs. Pine shares her recollections of the baby in the woods in these words:

The story as my husband Brian told it to me and to our children began one Saturday evening in June 1900. He was 10 years old. His father, Steve, came home from a long log drive up the river, seeming very sad and quiet. His wife asked him why and he told them that on the previous Wednesday afternoon the crew was working on the wings of a big logjam when one of the crew pushed his cant dog down between two of the logs, when he pulled it out a pillowcase sewed shut on both ends was impaled on the hook.

He started to open it but the worker yelled for him to toss it back in the river as it probably was another bag of Vanceboro cats, and they had no time to lose. At that moment he got the bag open and asked everyone if it looked like a cat. He stood there, and cradled in his hands was the pink body of a newborn baby girl.

The shanty boys took the wee body ashore on the American side, wrapped it in a new wool shirt and laid it to rest in a shallow grave scooped out in a hurry. Large rocks were piled over the shallow excavation, to protect it from curious bears. The awed men gathered with their fingers clutching sweat-soaked hats, some bowed prayer, some with tears in their eyes.

“Brian’s father was a white-water man and jam breaker. Two gates of water were all that could be spared from Spednick Dam and the Duck Point jam must be broken and the logs flushed down the river while the water level lasted. Minutes were precious and the men had to be summoned back to the heaving and pushing logs.”

The wee baby in the woods was not forgotten by these men, however, and in Mondays Maine Street, Mrs. Pine will describe the events of later years that resulted in this baby’s grave becoming a legend in the St. Croix area.

Bangor Daily News July 10, 1967, Ada Pine

POIGNANT SPOT

In Saturday’s Maine Street Mrs. Ada Pine of South Lincoln told how the grave of the unknown baby came into being early in the century on the bank of the St. Croix River. Today, she describes how the grave was cared for and became legend through the years in these words:

The following spring the tending out crew at Duck Point exhumed the body and a new resting place was prepared 30 feet back from the rushing river. The grave was rimmed with river rocks and outlined with a cedar fence. Later a thick piece of slate in the shape of an elongated triangle was polished and inscribed by the foreman Horace Keene, with these words: A child found in the river and buried here June 29, 1899.

Then began more than a half century of dedicated devotion to an unknown child. Each year as the shanty boys passed by, they would stop at the grave for a few moments in silence. Actual care was assumed by Horace Keene, until his death in 1930. By 1934 the last of the original log drivers had passed on, but the tale had been told and retold so many-times over the preceding 35 years it had become a St. Croix Legend. My husband Brian took over the years after Horace Keene’s death in caring for the grave. He kept the area in repair and the children kept it loaded with river flowers and water lilies. A few years before his death Brian replaced the cedar fence with a metal fence. The years of wind and rain had made the inscription on the slate illegible, and he carved a new marker out of cedar, duplicating the original epitaph.

After his father’s death, Milton picked up where his father had left off, caring for the grave until he moved away from Vanceboro a few years ago.

The mystery of the baby’s death has never been solved. The most common theory was that she had been tossed from a train passing over the international railroad bridge passing back and forth from Vanceboro.

I’ve been told that since Milton moved from Vanceboro, registered guides have been caring for the grave as they go back and forth from Vanceboro to Loon Bay with their sporting parties.

Ada Pine died November 13, 1968, in Lincoln. She was born in Vanceboro in 1901.

More recent photo of gravesite from St Croix Waterways Commission

Both Milton and Beryar Pine worked for the railroad stationed at the Vanceboro railyard. We wondered what happened after Beryar Pine passed on and his son Milton took over this sacred mission. Holly Beers assures us that although there are no longer any Pines in the area the grave is still maintained by folks on the river and the metal rail fence remains intact. Cindy Scott of Vanceboro was Cindy Crandlemire and still lives in Vanceboro with her husband Curtis Scott. She recalls her parents, Vance and Sharon Crandlemire together with Beecher and Jackie Scott and Robert and Kay Scoville making a special trip on Memorial Day every year to the baby’s grave to tend and decorate the grave. Cindy and her husband operate a canoe rental business on the river, and she says even today the grave is a special place where canoeists stop to pay their respects and share a moment of reflection.

It is difficult to visit the grave except from the river. The St. Croix Waterway commission maintains a campsite nearby appropriately named “Baby’s Grave”.