On December 3, 1893 the Boston Globe did a feature article on George Spratt, a fellow to whom the St Croix Valley owes a good deal, although his contributions have long since been obscured by the mists of time. Perhaps Calais folks disowned him after his 1864 hijacking of a Calais Civil War soldier, but more on that later.

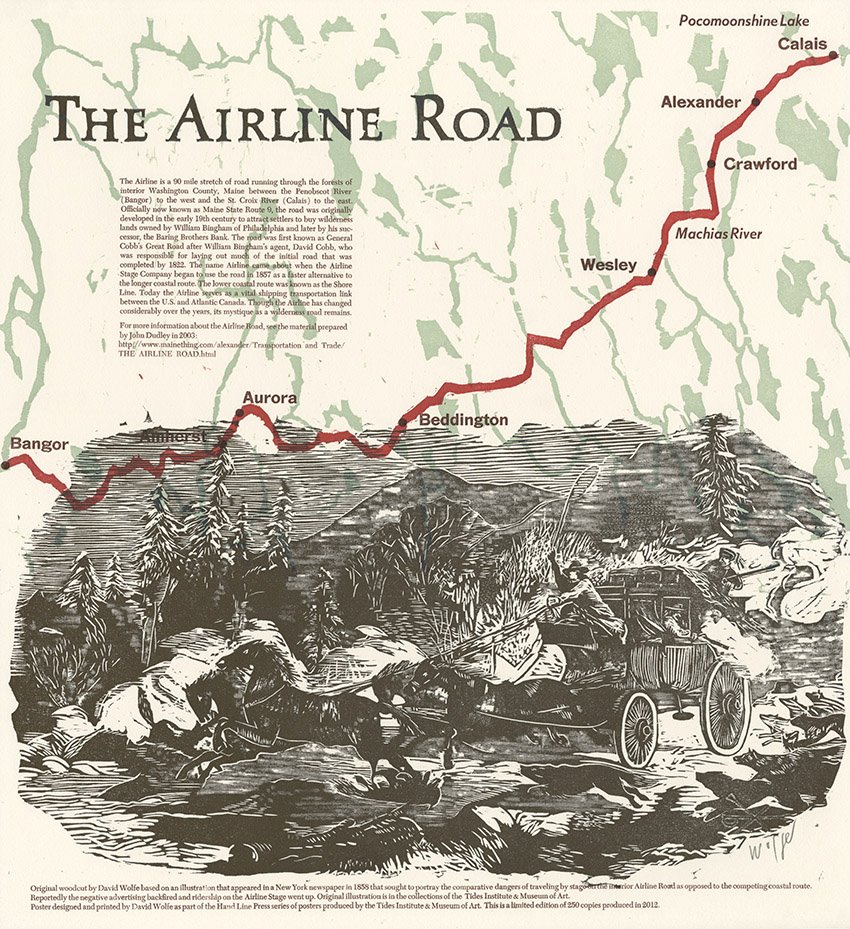

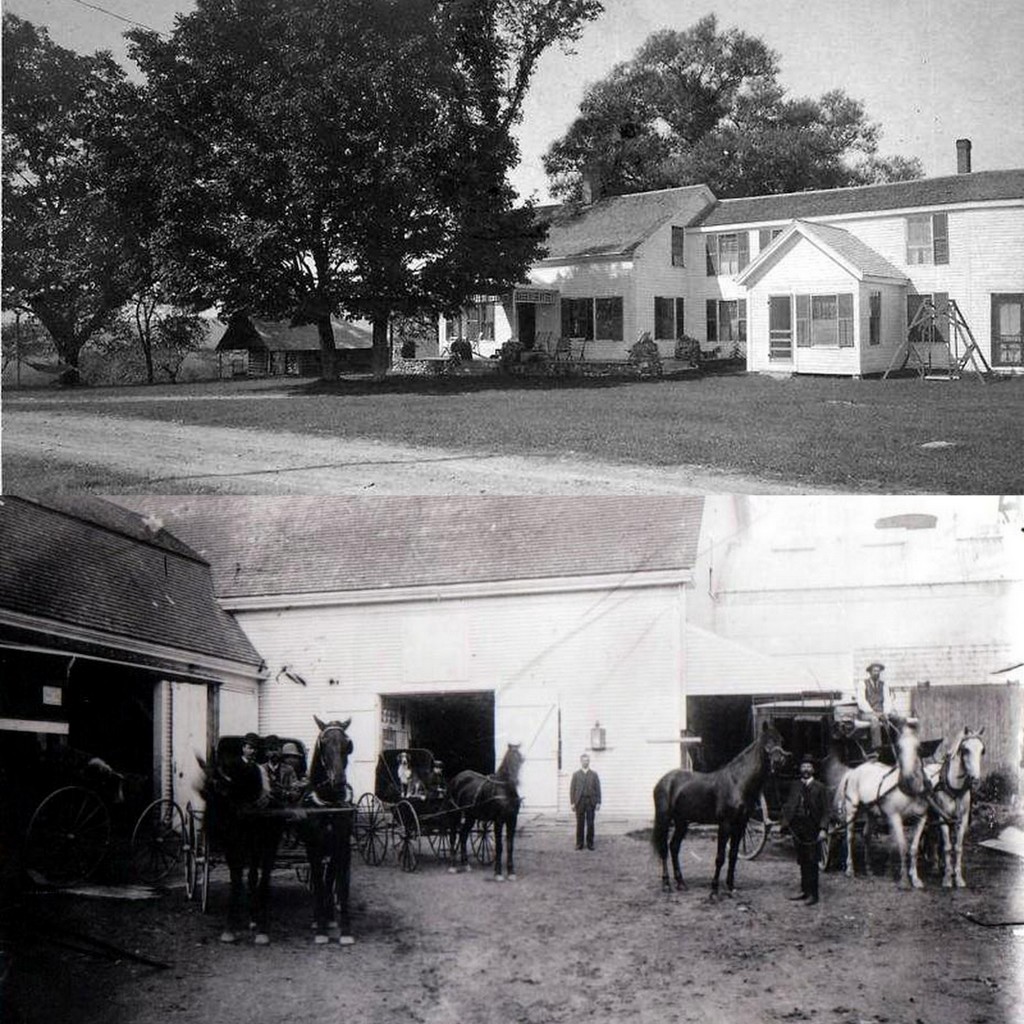

George Spratt was born in China Maine in 1822 and lived in both Calais and Bangor although primarily in Bangor in his later years. He owned livery stables in both cities and operated stagecoach lines Downeast, the most famous being the “Airline Stagecoach Line” for which Maine’s most famous road is named. Had George, when running a livery stable in Calais in the 1850s, not been challenged by local Calais merchants to prove it was possible to drive a team of horses through the wilderness which separated Wesley from the small communities east of Bangor, it is hard to say when, or if, the “Airline” with which Downeasters have such a love-hate relationship, would come into existence. Had it not been for George Spratt we might still be driving through Machias or across Route 6 to get to Bangor. Following is the 1893 article in its entirety with some photos and brief commentary added.

Boston Globe December 3, 1893

ATTACKED BY WOLVES.

Good Stories of Old Stage Days Down East.

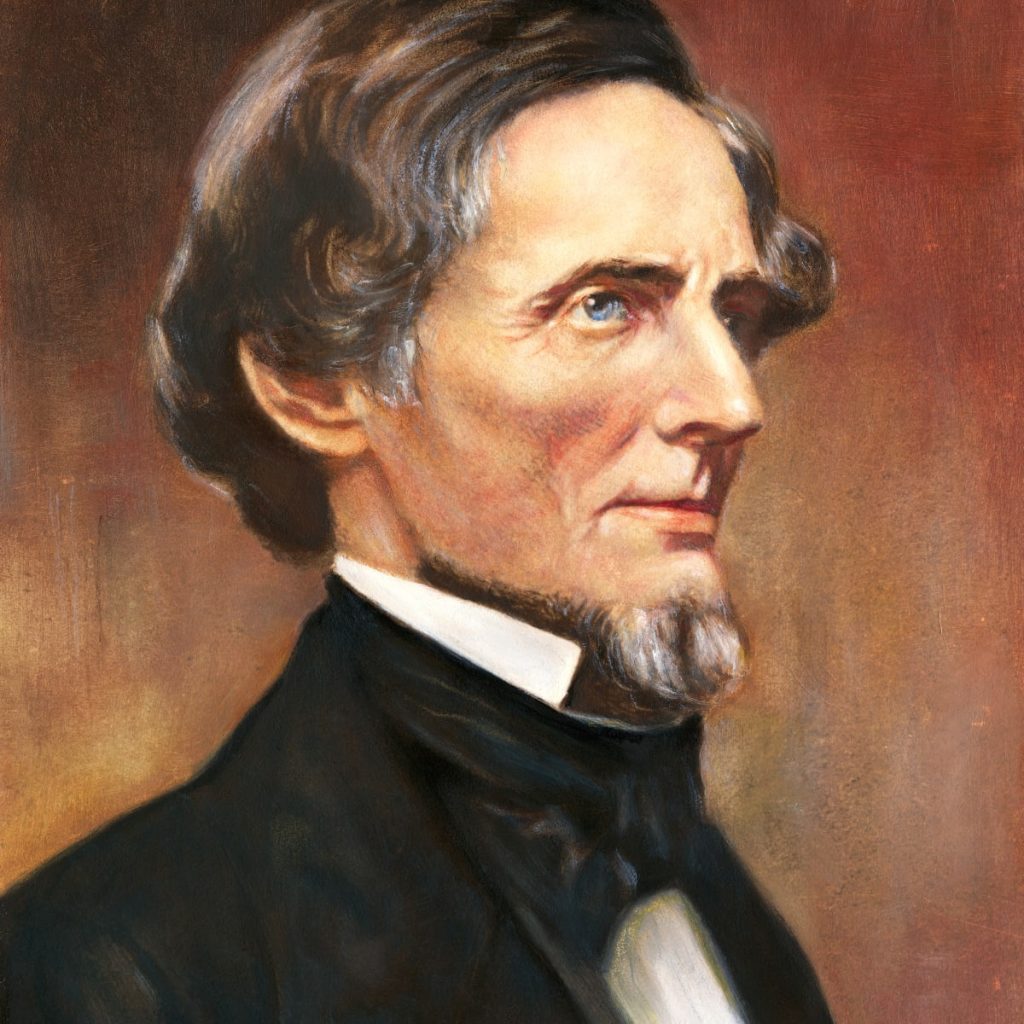

Driver Spratt Tells of the Time When Jefferson Davis Sat Beside Him.

Chief of the Confederacy Went to Muster and Gave Spratt a $100 Tip.

A familiar figure on the streets of Bangor is that of a tall, broad shouldered, powerfully built man, with neatly trimmed beard and hair of iron gray, whose quick movements, erectness and bluff, hearty voice show that he wears his years easier than most people. Genial manners, a keen sense of humor, which makes him fond of a joke, an invariable eye to business, and a store of reminiscences proclaim George W. Spratt a genuine Yankee. For years he has lived In Bangor, and the circumstances which led to his coming here go to compose an interesting bit of Maine history.

Mr. Spratt was the pioneer stagecoach proprietor from Bangor to Calais over the more than locally famous air line route, and his stories of staging it through the Maine wilderness in the early days are full of adventure and interest. Away back in 1856 Mr. Spratt was a livery stable keeper in Calais, when one day James S. Pike, a leading man of that period, who resided there, called on him and said George, I want you to drive me to Bangor, through Crawford and Wesley. Mr. Spratt was astonished, as such a route had never even been suggested, and he did not think his caller could be in earnest until it was explained to him that the caller and his friends were very much dissatisfied with the eastern mail service and proposed to find a shorter and easier route for transmitting the mails and then secure its adoption by the government.

The very next day the two men started west with a pair of horses. The roads were fair until Wesley was passed, and then for 60 miles there was nothing but a woods road used in winter by lumber men and which had never before seen a carriage or wagon of any kind. In this whole distance there were but three human habitations, and these log huts in the wilderness with but one regular occupant in each, while the forests were infested with wolves and the other large game for which Maine is famous.

But Mr. Spratt says that he and Mr. Pike made the initial journey in safety, avoiding all trouble, and soon after there came requests from Washington for proposals for carrying the mail via this route, the only stipulation being that six hours quicker time should be made than over the shore line, which followed the old road around the coast. Mr. Spratt secured the contract at $5000 per year, apportioned 86 horses to the work and in 1857 the line was opened. The stages used to leave Bangor at 9.30 p m, reaching Calais at 3.30 p m the next day. The first trip was made with one passenger and 15 pounds of mail but the airline was a happy hit, and the business soon grew beyond expectations, calling for larger coaches, drawn by four and six horses.

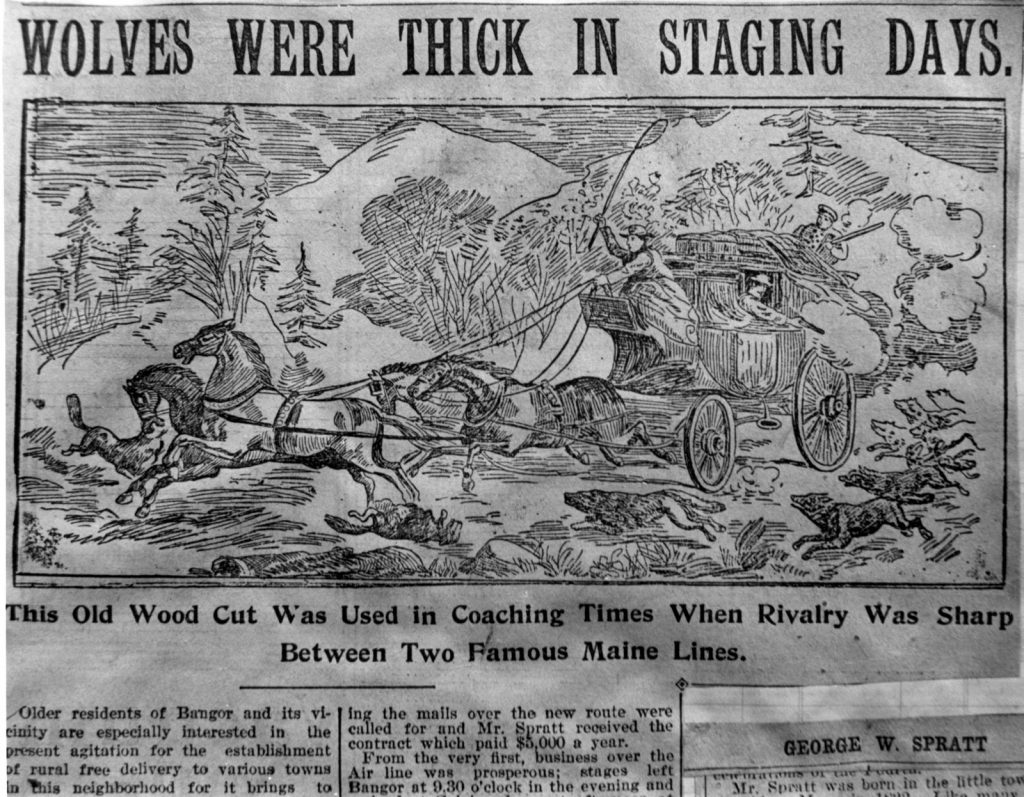

As only a tandem team could be driven over the old lumber thoroughfare Mr. Spratt took a crew of men and actually mowed the bushes and graded over many miles of the distance until it was in very fair shape at his own expense. The line was getting well established when the older one commenced fighting it. Both concerns employed runners and pullers who could make their fortunes attached to a Bowery clothing store in these modern days, and every east-bound traveler was buffeted among them until he completely lost his own idea of how he wanted to travel. It became generally known that for two score miles the new air line route was troubled with wolves, and the animals were heard nearly every trip chasing deer around the ponds which are so thickly sprinkled through the region, while their howling at night alarmed the drowsy and timid passengers and frequently sent the horses into a mad run, when all the skill, strength and courage of the driver were required to check them. These experiences with wolves, while sometimes startling, were never actually dangerous, except from the effect on the horses, for a single pistol shot into a pack would generally scatter them, but they caused no little concern among travelers and excited discussion among the natives. In fact, they gained such wide circulation that Gleason’s Pictorial, the leading illustrated paper of that day printed the accompanying cut, greatly enlarged, purporting to have been sketched by a participant in one of these wild encounters, and it occupied nearly half the first page of the paper.

The stages had trouble also with a lawless set which inhabited the section through which they passed, and were robbed once or twice, although no violence was shown either driver or passengers, only the mails strapped to the racks being disturbed.

But the combination of wolves and robbers furnished the opposition with a strong card, and their men so worked upon the nerves of would-be passengers with the harrowing tales that the shore line for two years or more, captured the cream of the business.

When the great wolf cut appeared in the illustrated paper, Mr. Spratt’s cup of business sorrows fairly ran over, it cost him hundreds of dollars. Even his own drivers grew nervous, and it was due about as much to the stories as to their actual experience on the line, although the latter was at times a little uncanny, it must be admitted. One of them went so far as to live in actual dread of his night run through the woods, and having no passengers one night, actually stuffed his well-filled mail bags into men’s clothing and bolstered them up on the seats to resemble men, driving through the night in that way. He afterwards earnestly declared that he saw robbers at a turn in the road, but they did not dare to molest the stage, owing to the large party of passengers on board, which they lacked the courage to attack.

But in spite of wolves, robbers and the efforts of the opposition, which extended even to cutting rates, the Airline slowly gained the prestige as a quick and short down east route which it has ever since held. It took years and energy to accomplish this result, but luckily Mr. Spratt had both. He was obliged to keep the road in repair himself for tens of miles in the utter absence of settlers. When there came a storm which carried away a corduroy bridge, made a washout or piled tree trunks in his way, his stages were frequently delayed and invariably the postal department would impose a heavy fine on account of it. Finally, this custom became unbearable and Mr. Pratt rebelled.

He made a concise statement of the existing conditions and the late Hannibal Hamlin, then in the U.S. senate, needed only a request to interest himself for the sturdy contractor with such good results that he had every dollar of the fines remitted. The drivers of the stages not only had to be tough, weather-hardened men, but able to cope with every emergency, like the true Maine pioneer. One driver, during a howling snowstorm, fought his way as far as Pine Mountain. where, in the face of a tremendous drift, his exhausted horses refused to drag their heavy load any farther and dropped in the snow. The passengers, and there were ladies among them, were powerless, and placed their lives in the driver’s keeping, not knowing that they were many miles from shelter, while night had already settled.

After vain attempts to start his team, the cool-headed driver placed the ladies on horseback and leading the way with the men actually fought his party to the camp of Geo. Black, a lumberman, two miles into the woods, over a logging road. Had a man with less pluck been their guide they would have perished. The next day Black with his crew of woodsmen and oxen found the sled, mail and baggage completely buried in the drift and were obliged to precede it to civilization, shoveling the snow from the road, as they moved slowly along.

The trouble with mail robbers reached its height during the war, and while the stage drivers were never molested, the utmost cunning was exhibited in carrying away the mail bags, which were then rich with money sent home by soldiers. At one time a most mysterious series or robberies was conducted. The mail pouch containing valuable letters would be given to the driver at Bangor and strapped on the top of the coach.

At Amherst, where horses and drivers were changed in the early hours of the morning, it would be found undisturbed, and the new driver would receipt for it but upon reaching Calais the pouch would be missing. This continued for some time, the thief baffling detection until the post office department took hold of the case. It was found that the stage halted at Amherst close to a high board fence, behind which the thief was secreted. He would wait until an inspection by the drivers had shown the mail pouch to be safe and would then reach over and seize it, taking it into the woods and rifling it. When arrested the fellow was able to restore only a large number of soldiers’ letters and pictures sent home from the front, but these were worth more than gold to the anxious families of the men, owing to the dreadful fears aroused by the long silence.

The ingenious rascal who had been doing such a thriving business in the Amherst stable yard went to the state prison for 15 years. There was still more trouble with a set of men known as the Millers who kept a noted dive with the report of all kinds of lawless characters, which they called “Bull Run.” The Millers had an interesting custom of secreting themselves in a dense thicket at the foot of a long hill, and when the stage passed to steal out and creep behind it up the ascending ground long enough to cut the mail bags from the rack. This practice was soon discovered, and the Millers reposed for a term of 10 years in prison at Thomaston to pay for the exercise of their theft.

One of Mr. Spratt’s most interesting recollections is of the time he drove Jefferson Davis over the Air Line. It was in 1858, and Mr. Davis, who had just retired as secretary of war, came to Maine to get some idea of our military strength. He attended the state muster at Belfast, which, because of his visit, was made one of the most memorable that Maine ever knew, and then came to Bangor on the steamer Daniel Webster. Prof Bates of the U S coast survey, with a large party, including ladies and a retinue of servants, had arrived here 10 days before and gone into camp at Lead Mountain on Machias waters in most elaborate style and invited Mr. Davis to become his guest. The invitation was accepted, and Mr. Spratt himself took charge of this distinguished party.

On the return trip, as they were changing horses at Amherst, the southern chieftain paced back and forth in the tavern yard, smoking a cigar and evidently in deep thought. Just before all was in readiness for a start Mr. Spratt approached him and said: Mr. Davis, you are the first southern man I have ever met, and I would like to have a talk with you. Won’t you come up on the driver’s seat with me and ride a while? I would he very glad to do so, replied Davis, and he proceeded to follow his words by action. He rode, the entire distance to Bangor with Mr. Spratt, and they talked busily through the long hours, the southerner freely answering all questions and discoursing at length upon slave life and the position of the south, the customs and temperament of the people and upon all the subjects which were at that time uppermost in the public mind. He seemingly talked without much reserve, and his driver did the same, the time passing very quickly.

Reaching this city Mr. Davis alighted at the Bangor house, where the leading men of the city were fast gathering to greet him, as befitted his position. He had already expressed his delight at the drive through the varied scenery. He looked up through the clouds of steam which rose from the panting stage horses and said, with a smile: Mr. Spratt, please come into the house with me. I want to see you alone. In just a moment Mr. Pratt went in, and when he returned a minute later he was also smiling, for in his hand was a bright new $100 bill Mr. Davis pressed that upon him in addition to his warmest thanks.

Some great time was made over this air-line road despite its roughness, and Mr. Pratt, who never in his life sat behind a poor horse when he could help it, has traversed the distance as speedily as anybody.

One instance in particular, he recalls with no little gratification, and he is not alone in his recollection of it. It was in the latter days of the war, when the draft had been exercised unstintingly, and men who would enter the service were worth $2000 or more to the towns which they represented. Way down on the border (Calais) was a man whom a rich Bangorean had obtained as a substitute, but who was also sorely needed to make up the quota from the town in which he lived. Clever, quick and energetic work was required to smuggle him from the locality and Mr. Spratt was selected for the mission and started behind a famous local roadster of those days called the Pierce mare, the dame, by the way, of. Ezra L, the great Maine trotter of 15 years ago.

After an airy drive of a lot of miles Mr. Spratt secured his man and the next morning started for Bangor with a rush, knowing full well that he would be pursued. Less than 30 minutes later the town officials heard of the raid made upon their already minute supply of available recruits, and, with the fastest horses to be obtained, started in pursuit of the cheeky Bangor man. They drove until their horse seemed fagged, and, reining up at a roadside tavern, asked for the best horse in its stable and eagerly inquired for Spratt. The innkeeper said that he had passed there an hour ago. An hour ago, they almost yelled. Why, he only had 30 minutes start out of Calais, and we’ve been coming like the very devil! That’s all right, said the landlord with exasperating coolness, but Spratt was going like two devils! No time was lost in getting a fresh start, and after another stretch or many miles had been covered, the men from the St Croix found that Mr. Spratt had gained another half-hour, having passed the point of inquiry an hour and one-half before. Another fresh horse was obtained, and soon after starting with him the pursuers reached the top of a great hill, and on another, two miles ahead, saw the fugitives driving from a dooryard. They had stopped over an hour for rest and refreshments for themselves and their horse, only resuming their journey when they saw the officers coming.

Spratt drove into Bangor miles ahead of the others, and by the time they arrived the substitute was beyond their reach. He says that he has never known that drive, 100 miles in a single day, over a forest road, with but one horse, hauling two men in a wagon, and distancing three relays of fresh horses in pursuit, to be equaled these parts. He tells the story with a degree of pride which can be easily understood, for this achievement is a well-recorded bit of local history.

We cannot say for certain when George Spratt died but a newspaper article in 1908 found him in Bangor and still hail and hearty:

Mr. Spratt has always lived an active life in spite of his 86 years. He has lived according to his desires, always temperate in eating and drinking and smoking, but enjoying them all as the men of the old guard did and still do, who survive. Mr. Spratt stands near 6 feet tall and it is big in proportion, with clear eyes white healthy skin and white hair and beard. He says he wants to meet a man anywhere near his age who can put him down in a wrestling match.

As to his place in the hearts of St. Croix Valley folks there is, on the plus side, his intrepid spirit and courage which gave us the Airline and even though he seems to have switched his allegiance to Bangor with the theft of Calais recruit during the Civil War, we have to conclude that on balance he deserves a favored place in the history of the St. Croix Valley.