ske·dad·dle

/skəˈdadl/

Verb INFORMAL

depart quickly or hurriedly; run away.

"when he saw us, he skedaddled"

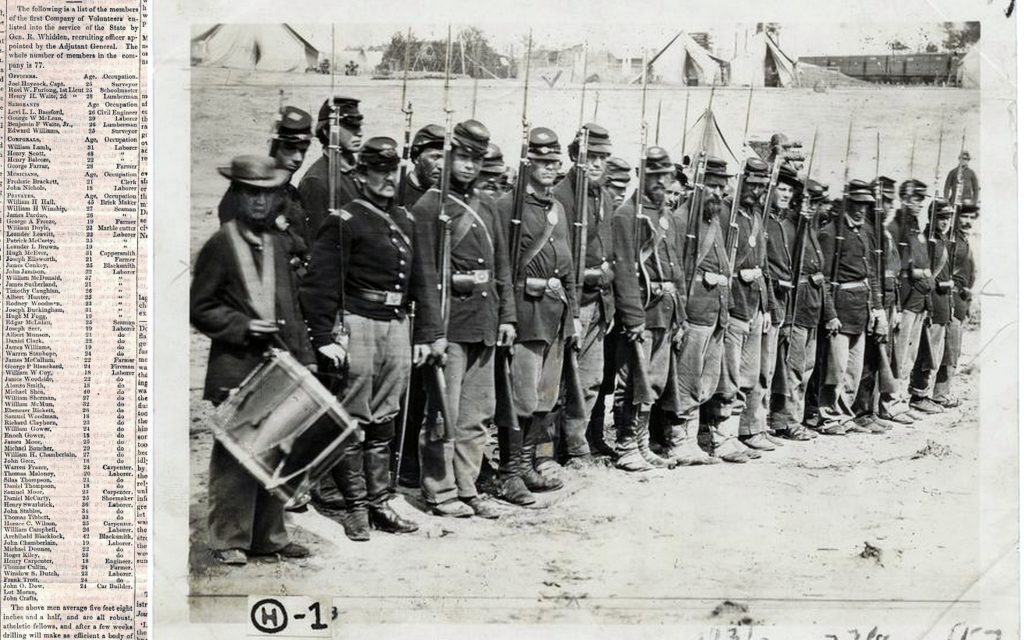

Although we have written a good deal on the St. Croix Valley and the Civil War, there is one aspect of the war we have neglected. The photo above shows a contingent of Maine soldiers after the battle of Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg Virginia in May of 1863. To the left is the roster of the first Calais company of volunteers to join the fight in May of 1861 – only a few weeks after war was declared. This company suffered horrendous casualties in the taking of Marye’s Heights. In fact all the officers from the unit died at Marye’s Heights or soon thereafter at Rappahannock Station and of the dozen officers and NCOs only three were not killed, wounded or disabled. The enlisted ranks suffered equally.

However, not all Mainers showed such willingness to sacrifice to save the nation, especially after reports from the early battlefields revealed the true horror of the conflict. Some refused to serve, deserted or dodged the draft when it was instituted in 1863 to make up for the shortfall of volunteers and therein lies the largely forgotten story of a small community about six miles north of the Maine community of Forest City, just across the line in New Brunswick, which became known as “Skedaddler’s Ridge”.

In 1956 our own Ned Lamb, about whom we wrote a couple of weeks ago, had to set the record straight on the meaning of the word “Skedaddler” which a writer in the Bangor Daily News claimed referred to Union soldiers in general. Ned wrote to the paper to correct this obvious error:

From Bangor Daily News March 2, 1956:

MORE ON SKEDADDLE:

In a recent item in Maine Street, a contributor used the word “skedaddle” with reference to the soldiers in the Union Army.

H.E. Lamb of Milltown Maine forwarded us further information about the word. Says Lamb: “The word Skedaddle did not refer to soldiers in the Union Army but to men who did not want to become soldiers. If you get a chance to pay me a visit, I’ll take you over across “The Line” and see that you get back and show you Skedaddle Ridge in New Brunswick where so many men went from this region. That’s how it got the name. Here in Calais they did not have to go that far but just crossed Ferry Point covered bridge and lived in St. Stephen. By no means did all men of draft age do this because 500 men from this region went to the Civil War. We have a beautiful monument here in commemoration of their actions.

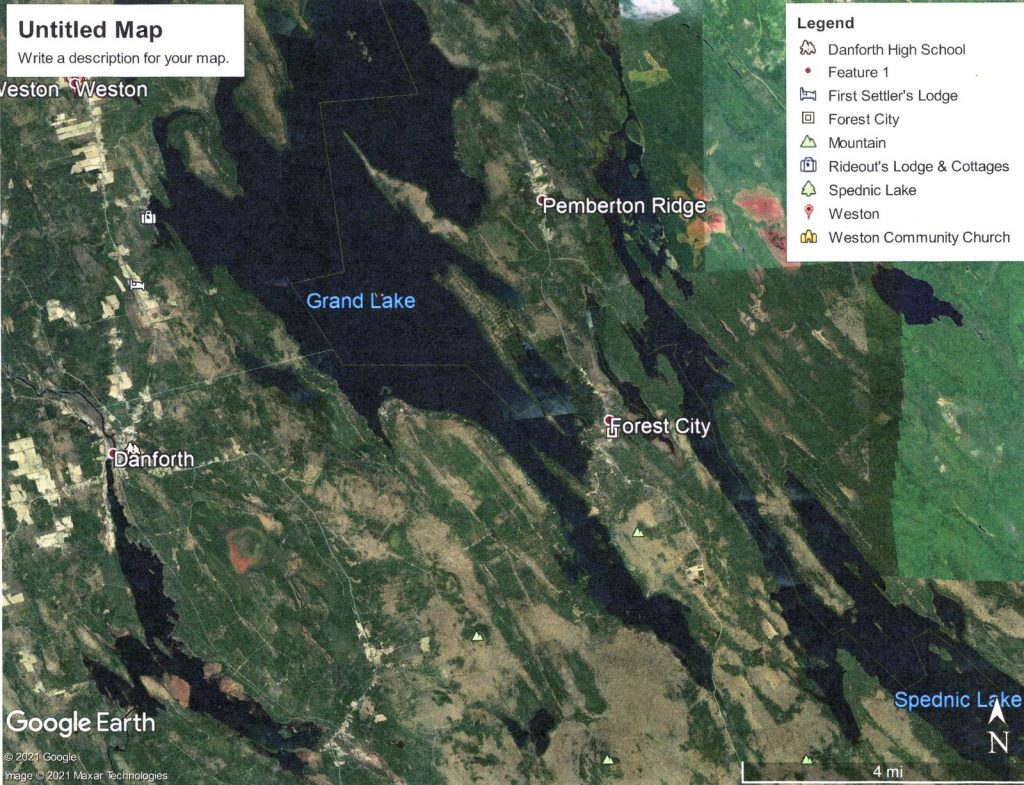

The place across “The Line” to which Ned offered to take the Bangor Daily writer is now known as Pemberton Ridge on the Canadian side. It overlooks Spednic Lake and during the Civil War it was known as “Skedaddler’s Ridge” as a number of draft dodgers and perhaps some deserters established a small community on the ridge.

Local historians Harold Davis and Doug Doughterty mention “Skedaddle Ridge” in their histories of this area as a settlement where draft dodgers and deserters from the Civil War hid from the law during the war. While the settlement itself was established after the institution of the draft in the summer of 1863, some reports say the first group of “draft dodgers” actually crossed Spednic Lake in the winter of that year to avoid Federal conscription. However, going across “The Line” to avoid service actually began in 1862 when the Maine Governor suggested a state draft was a possibility. The Calais Advertiser was outraged that men would flee to Canada to avoid fighting to save the Union, especially as a draft was only suggested as a possibility.

Calais Advertiser July 17, 1862

A VERY POOR SUBJECT

We understand there are more than 50 persons, wearing the apparel of men, who hail from Penobscot and thereabout, now boarding with our neighbors over the river.

There are also half a dozen from this vicinity. These people are fugitives of the meanest sort.

We have compassion for the unfortunate who runs away from the flogging of an overseer, for an apprentice who escapes from the tyranny of a taskmaster, for a sailor who can no longer put up with brutality of his captain, but for the chap who now-a-days runs away from the fear of this draft, we have no feeling but such contempt and disgust as cannot be expressed in words.

How ridiculously small, the cause of the scare. The Governor gives notice that a draft may be resorted to if a sufficient number of volunteers are not obtained seasonably. Suppose there were no volunteers in the State, it would take one enrolled man in seven. This is the worst chance of being drafted. One in seven. If it turned up that a body turned up number seven, in this drawing, he could get clear by paying fifty dollars or finding a substitute.

It then comes to this, that these fellows ran away for one seventh part of the danger of being obliged to pay fifty dollars or, to be exact, they ran away on account of seven dollars and fourteen cents, and two tenth of a cent.

Yes, seven dollars and fourteen cents have driven these men from home, and kindred, and business, among strangers and aliens. Seven dollars and fourteen cents have taken from them comfort, self-respect, peace of mind, the regard and esteem of all men. For seven dollars and fourteen cents they have sold out all that gives value to a man-his character. For seven dollars and fourteen cents they sneaked away from home and fled out of the State, looking over their shoulders after the Sergeant in full chase, suffered the quivering of the knees and coldness of the stomach which attends the pains of cowardice.

It was poor economy anyhow. It will cost each of these scarecrows more than the whole of the fifty dollars to get to the Provinces and back, let alone the damage of leaving business.

After all there will be no draft and there has never been any danger of it, and the journey has been for nothing, not even the saving of seven dollars and fourteen cents.

We advise these sneaks to take the track back at once, swear they only went a few miles on business, ignore all knowledge of the Province, and counterfeit thereafter the semblance of men. If there should be talk of another draft, they may change clothing with their female acquaintances, deny their sex, and give an equal number of brave women the chance they desire of shouldering a musket and wearing brass buttons.

We shall endeavor to procure their names and publish them for the information of the State, in hopes they may be known and despised by all men. We assure our neighbors over the river, who have true English admiration of manliness, that these fellows are real peacemen, whose ears may be cuffed and whose noses may be pulled in perfect safety. We hope these runaway scallywags accordingly meet with such treatment as will make their new quarters most uncomfortable.

While the Advertiser article does not mention Skedaddle Ridge specifically, the number of “Skedaddlers” mentioned conforms with later descriptions of the community. Certainly by 1863 Skedaddle Ridge had become a settled community and was a topic of articles in the national press like one in the Detroit Free Press of December 23, 1863:

Detroit Free Press 23 December 1863:

A New Settlement- “Skedaddlers Ridge”- On the western margin of the grand lakes, abreast the town of Weston Maine and on the New Brunswick side of the line, a settlement has sprung up, which goes by the name of Skedaddler’s Ridge” and the dwellers have fled their country because of mortal fear of the draft. This craven-hearted community now numbers about 50, and their number is gradually increasing. Although the Province people are generally delighted to witness our national imbroglio, yet they have little respect for those who forsake their country in the time their aid is needed.

Both the Advertiser and Ned Lamb identify the majority of the “Skedaddlers” as being “Penobscot Men” with perhaps a few locals joining the community. From the rare contemporary reports it does seem the community remained relatively small although large enough to perhaps support a school and a church. As to life in the community we know little to nothing as no account of any of the inhabitants exists. It was apparently short-lived, lasting only so long as there was the threat of conscription. After the war it is assumed most of the “Skedaddlers” drifted back across “The Line” to hearth and home although their reception was probably a bit frosty. There is some indication in an article in Wikipedia that some of the “skedaddlers” remained in Canada.

This is not to say that “Skedaddler’s Ridge” exists today only in ancient and musty newspaper accounts or historical publications. For those who fancy a walk in the woods the remains of the community are relatively easy to find and several have made the effort. In an undated newspaper article, writer Jim Byrd recounts his visit to the site, probably in the 1980s:

“Shedaddle Ridge was located close to the old coach road between St. Stephen and Woodstock providing a quick means of escaping Union soldiers. This road also gave the settlement a means of transporting its products and inhabitants to other communities.

Settling on a ridge provided a defensive posture. In the event of Union soldiers trying to reach the area the settlers had the advantage of high ground. There could be no surprises.

The “Skedaddlers” chose a site near the communities of St. Croix and McAdam but far enough away and isolated enough so as not to attract unwanted attention.

But what of the settlement today?

The site of the former settlement is overgrown by a variety of trees and brush. However, there is ample evidence of the land having been cleared at one time. We traversed the site, coming upon several piles of moss-covered rocks which stretched throughout the forest. Some of these piles stretched as far as we could see. Clearly these piles were man made.

Another engaging aspect of the site was the several square and rectangular holes dotting the site. These appeared to be cellars, although no sign of the original structures remained. Many were overgrown with brush or partially caved in. Close to one of these holes was what appeared to be a well. It was lined with rocks, many of which had fallen in.

The most fascinating feature of the settlement was what appeared to be a graveyard. Scattered throughout a small space were several flagstones, none of which contained any markings. Some were lying on the ground. Others were propped up against trees with others appearing to be planted in the ground. Perhaps they were the graves of children, children who spent but a few short years on “Skedaddler Ridge”.

In 1985 the St. Croix Waterway Commission conducted a survey of the Skedaddler Ridge site finding many cellar holes, stone walls, the cemetery mentioned by Byrd and a cast iron stove marked with the date of 1857. The report states “The site has been protected for the last 100 years by its isolation.”

As late as 1993 the King’s Landing Historical Commision featured New Brunswick’s contribution in the Civil War and Skedaddler’s Ridge in an historical reenactment

Bangor Daily news Sept 10 1993

New Brunswick celebration seeks Civil War deserters

By Ross Ingram

Special to the NEWS FREDERICTON New Brunswick — Both the Blue and the Grey will be busy Sept 18-1963 at Kings Landing New Brunswick’s historical settlement west of Fredericton. They’ll be looking for deserters from both the armies of the North and the South who managed to make it across Skedaddle Ridge into New Brunswick. The reenactment of a portion of 19th-century history will be made possible by the visit to King’s Landing of the 20th Maine Infantry, the 3rd Maine and the Maine Heavy Artillery along with their camp followers. The American visitors will perform military drills of the Civil War period, will skirmish with “southern” troops and will set up period campsites. Saturday afternoon foraging parties will visit the historic homes at Kings Landing looking for food and attempting to pay for it with Confederate banknotes. It’s no accident that some New Brunswickers are included on the rolls of the modern day versions of these honored Maine regiments. During the Civil War Canada was still a British colony but some 54000 Canadians joined the Union Army, the same number who joined the US Army a century later during the Vietnam War. New recruits received $300 for signing on the dotted line and $14 a month thereafter. Canadians enlisted for many reasons a sense of adventure, support for the anti-slavery concept or just employment. Some of the more enterprising would enlist, take the bonus desert travel to another Canadian border community, enlist under another name and pick up another $300. Many of the regimental records still exist with Canadian towns and villages- listed as home towns. The only part of the Civil War that actually spilled into Canada were border raids by sometimes sizable Confederate forces hiding in Canada to destroy American bridges, railroads and supply depots giving aid and comfort to the Union troops. The most famous of these raids was on the Vermont town of St Albans when a Confederate force robbed six banks and returned to Montreal with just a few casualties. In fact Booth, President Lincoln’s assassin, also operated out of Montreal. Union forces in pursuit of the Confederate quarry usually ignored the Canadian border and carried the pursuit well into Canadian territory. The first US draft law passed in 1863 allowed those not wishing to serve in the Union Army to purchase a substitute. Those who didn’t or couldn’t usually jumped the line into Canada. They were called “skedaddlers” and Skedaddle Ridge near Canterbury on the Maine border at Forest City was a popular spot for “crossing the line”. There’ll also be 1860s-vintage games during the historical weekend at Kings Landing when local residents and visiting military will compete in lumberjack events and contests of strength, agility and endurance for the title “Bull of the Woods”.

The suggestion above that there was easy money to be made by enlisting for the $300 bonus, deserting and reenlisting under another name for another bonus was not lost on the truly unscrupulous but it was a very dangerous proposition. As Ken Ross notes in his remarkable Civil War history of Washington County:

Deserters risked a variety of penalties. If caught, a man might be imprisoned in the nearest available Union jail. He might be pursued to his hometown and arrested. Washington County’s location, as in the case of draft evasion, made capture more difficult. According to one study, an estimated 200,000 Union soldiers deserted, resulting in 80,000 arrests and 147 executions. Of those executed, only 5 came from Maine, and none from Washington County. Others convicted of desertion incurred prison sentences or unpleasant assignments.

In all probability, a death penalty would apply to a “bounty jumper,” one who repeatedly enlisted for the bounty money and deserted as soon as possible. Such offenders might be brought before assembled troops to have charges read, then executed by hanging or firing squad. Wagoner Daniel S. Seavey (Crawford) of Co G 11th witnessed five such executions in the winter and spring of 1865. Of the last he commented, “March 11…I sat on my wagon and saw a man shot. These men are shot for trying to desert to the enemy and are taken outside the picket line” (Seavey, 12). New Brunswick became a haven for draft-dodgers. The law did not require extradition, and each new draft call drove more men eastward. Washington County residents could easily reach New Brunswick by boat or on foot, and stagecoaches carried men from farther west. They settled in places dubbed “Skedaddle Ridge” near St. Stephen and “Skedaddler’s Reach” on Campobello. New Brunswickers tolerated but did not admire them.

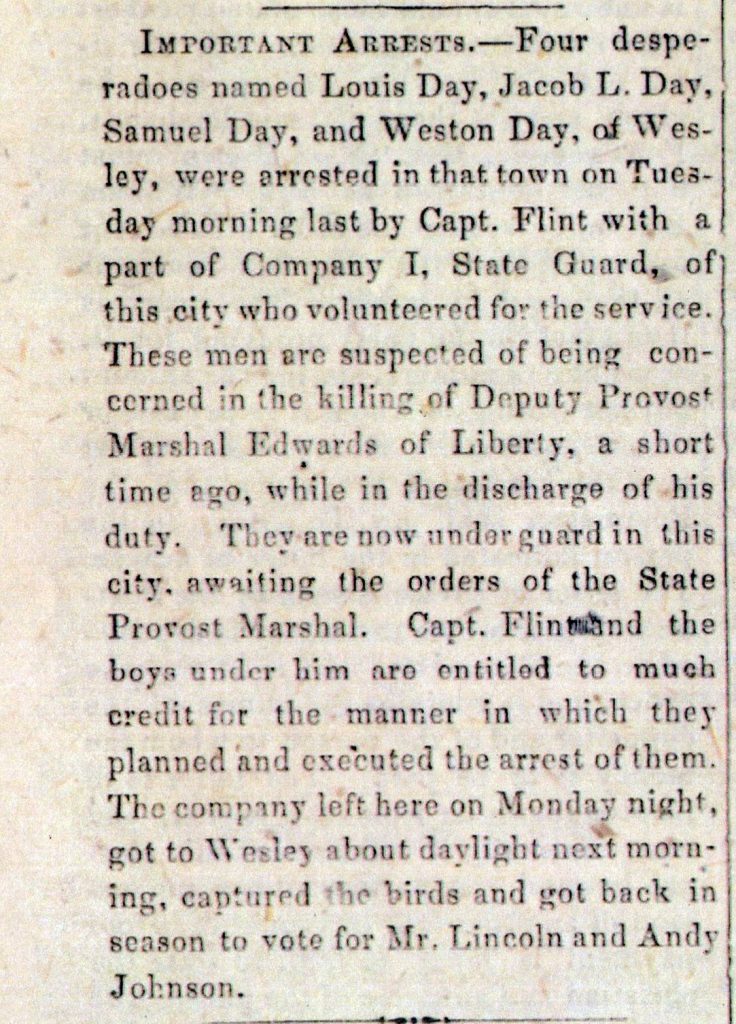

While resistance to the draft was not high in Washington County, generally there were pockets of resistance, most notably in Wesley where the Day family were vehement and violent “Copperheads” – a term used to describe those who opposed the war and the use of national power to free the slaves and save the Union. Again Ken Ross describes the confrontation in Wesley which resulted in the death of a U.S Provost Marshall who had been sent to Wesley to enforce the draft

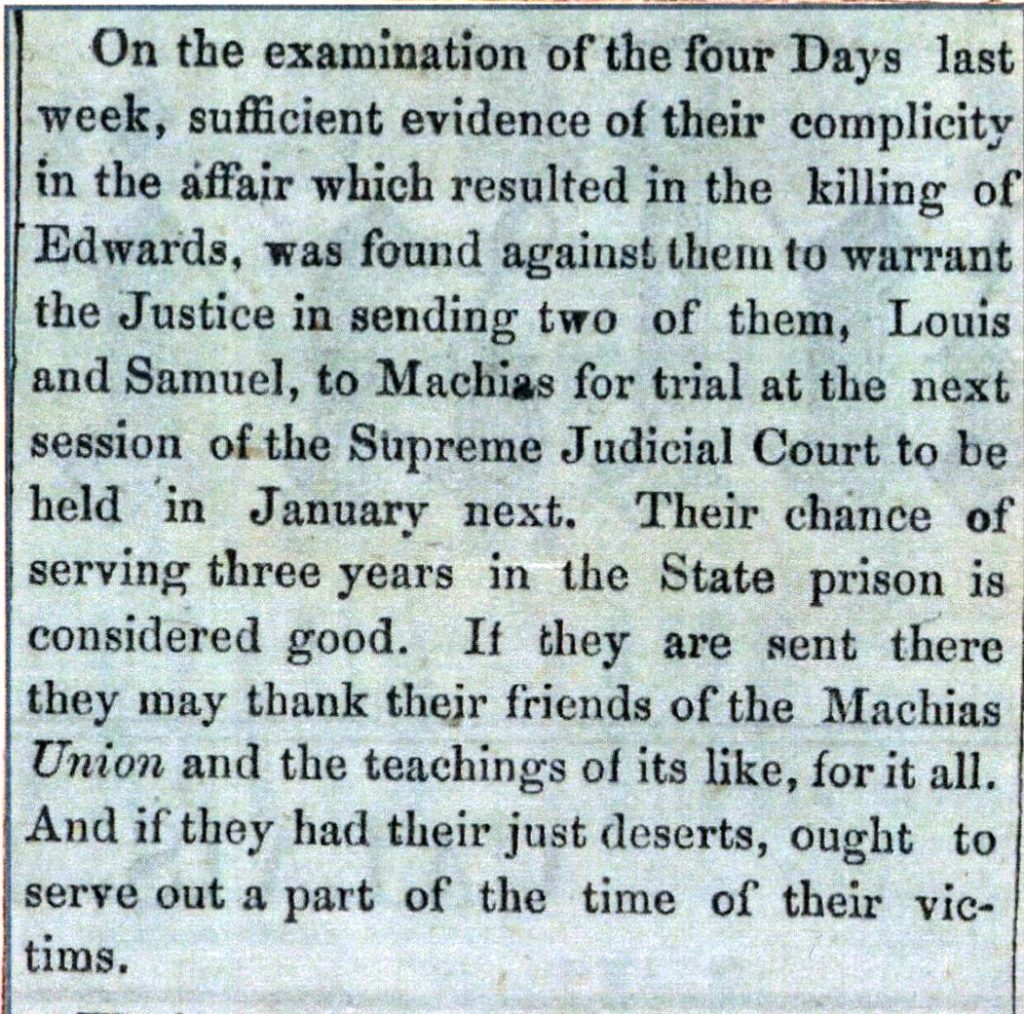

An attempt by agent Clark Perry of Machias to serve a draft notice on one of the Day men in Wesley in fall 1864 met armed resistance. Perry returned with two deputy provost marshals on October 13. As they approached the home of Elias F. Day, a gang ambushed them and killed Deputy Provost Marshal David W. Edwards of Montville, Waldo County. Hearing that the suspects had returned home to vote, a contingent of the Calais State Guards under Capt. Benjamin Flint went out at night, surrounded their homes, arrested them, and escorted them to Calais to be held for trial. 11/18/64).

Benjamin Flint had arrested seven of the Day men: Elias F, Lewis, Samuel, Willard, Gilbert, Jacob, and Jacob Lincoln Day. On November 15 in Calais, Judge George E. Downes tried Samuel, Lewis, Jacob, and Jacob L. for resisting the draft, and discharged them. Samuel and Lewis remained in jail at Machias until January 1865 when a grand jury declined to indict them for murder. Notwithstanding the gravity of murder of a federal official, the sole incident of its kind in Maine during the war, no one spent more than a few weeks in jail for it.

Most of the citizens of Wesley leaned Democratic and had little sympathy for the war. The Eastport Sentinel editorialized:

The murderer, Day, is said to be a young man of deficient intellect, a victim to Copperhead teachings. He had been told that the draft is unconstitutional, that Lincoln is a tyrant, that the war is a wicked one, and ought to be stopped, and he simply carried out the teachings of wiser villains.

One of the Days, John Wilbur, had joined the 28th Maine Infantry and died of disease on February 24, 1863. Two others, Abijah and Jacob L. would later be drafted as would most of the men from Wesley who did military service during the war (AG Reports).

We do know the Day boys were not the only ones in Wesley who objected to the draft. According to a family history, Jesse Huff and his wife Harriett (Gray) Huff skedaddled to Canada after Jesse had been drafted. We do not know if they settled on Skedaddler’s Ridge. He died in a stagecoach accident in New Brunswick and when his wife died soon thereafter their children returned to Wesley to live with their grandfather Joseph Gray. The family history also states “A few others from Wesley also went” to Canada to avoid the draft.

However, Washington County enlistment rates were some of the highest in the country – aided a good deal by New Brunswickers crossing “The Line” to sign up. For every “Skedaddler” there were probably several from the Provinces who took his place in the Union Army so in the end the Confederates did not benefit from the porous border with our close neighbors across “The Line”.

We want to thank Frank Carroll of McAdam for providing us with much of the information quoted above.