The tragic death of the swimmer near Bailey’s Island last week which, we are told, resulted from an attack by a “Great White” shark, was so rare an event that it was national news, reported in the Times, the major networks and CNN. According to the reports such a fatal attack had never before occurred in Maine and only twice in recorded history in the seas off New England. We did some research in our archives and could find no record of a shark attacking a human Downeast but did find some interesting information about sharks locally which we thought of interest.

The October 1880 edition of Scribner’s Monthly contained an article and the drawing above about the Passamaquoddy tradition of hunting porpoise in the bay, the fish being a primary source of food and oil for the Tribe since its arrival at the mouth of the St. Croix about ten thousand years ago.

Regarding sharks the article says:

Not unfrequently, as the Indian hastily paddles up to dispatch a wounded porpoise with his spear, he sees the terrible dorsal-fin of a shark appear, cutting the water, as the monster, attracted by the scent of blood, rushes to dispute possession of the prey. Although, there are well authenticated cases of a shark’s having actually cut the porpoise in half just as the Indian was hauling it aboard of his canoe, I have never heard of any harm resulting to the Indians from attacks of this nature; nor do they in the least fear the sharks, but, on the contrary, boldly attack and drive them off with their long spears.

Of course we don’t know what type of shark was challenging the hunters but the Great White can be 15 feet long, weighing several hundred pounds; and while the article claims the Passamaquoddies had not the least fear of the sharks, it is hard to imagine a shark capable of cutting “the porpoise in half” would not, on some occasions over the centuries, have managed to upend the canoe and devour a hunter. If so, there may well have been many humans killed by sharks Downeast in the past and once again we need to be conscious that the history of the white man in the St. Croix Valley encompasses a very small fraction of the valley’s human history.

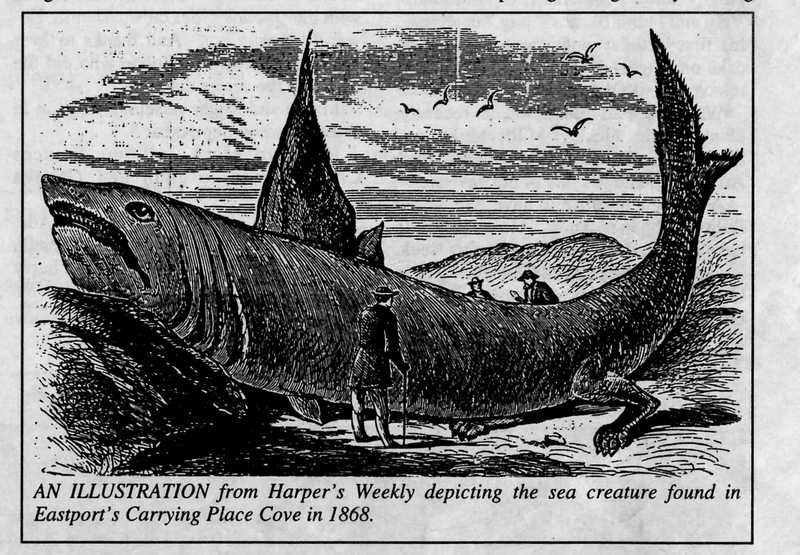

For the most part, sharks Downeast became news in connection with local “sea monster” tale. The best-known and the subject of a fine article in the Eastport Sentinel by Wayne Wilcox in August 1996 featured a large fish taken at the Carrying Place in Eastport in August 1868. The fish, although initially only described by the Sentinel as a “large fish” soon became the “Great Shark-Dog Fish” and by the time a stuffed version had arrived at the Boston Zoological Institute where it could be seen for a quarter, it had been elevated to the status of the “Great Utopia Lake Sea Serpent.” Lake Utopia got into the act because a large “Sea Serpent” had allegedly been spotted in Lake Utopia near St. George New Brunswick a few weeks earlier and the two were conflated in the minds of the public and in the plans of the serpent’s promoters to better exploit their monster. Harper’s Weekly was quick to provide an article on the serpent in its October issue complete with the illustration above. The contemporary accounts of the serpent’s capture from the Eastport Sentinel are provided below:

Eastport Sentinel, August 5, 1868:

A large fish was discovered in the Cove at the Carrying Place on Sunday morning last, a huge fin making its appearance above water. Four men took a boat and armed with guns, spears and axes gave chase, and after four hours of hard labor they succeeded in killing the monster. The fish was sluggish in his movements and made no demonstrations “against his assailants.” Its length was thirty feet and its thickness five feet three inches. Its tail measured seven feet in width. It had five rows of gills, and a blunt nose somewhat resembling the snout of a hog. Our sea-faring men who have visited the fish differ as to its species but agree it is a kind of shark. It was on exhibition at the Carrying Place on Monday and Tuesday.

After writing the above we learn that the proper name of the fish is “Shark Dog Fish.” It is found in the Northern Polar regions and is rarely seen in this latitude. Warren Brown has purchased the skin of the fish and will prepare it to be exhibited.

Eastport Sentinel, August 26, 1868:

We understand that Mr. Brown’s “Great Shark Dog-fish which is now on exhibition at Calais attracts great attention and are glad to learn that his enterprise is likely to be successful in a pecuniary point of view. Although Eastport has become somewhat noted for odd fishes, no animal of this kind has created so much excitement here since the well-remembered capture of the whale in whose flesh was imbedded a harpoon, marked with the mysterious CCL.

Eastport Sentinel, September 9, 1868:

The St. Croix Courier says Mr. Warren Brown has received several offers from persons wishing to buy the Shark Dogfish, which was recently captured at this place, and is now on exhibition at Calais; one of the offers reached two thousand five hundred dollars.

Eastport Sentinel, September 30, 1868:

Mr. Warren Brown’s monster fish, which is now on exhibition through the state, was lately exhibited on the Fair Grounds at Ellsworth, where the Fair was being held, and was noticed in the American, as the “Great Utopia Lake Sea Serpent.” This is an improvement on “Shark Dog-Fish.”

The Sentinel had a short memory when it suggested the “Lake Sea Serpent” was somehow unique in the annals of Passamaquoddy Bay history. Only nine years earlier in 1859 the Sentinel had written about the capture and exploitation of a very similar creature in 1829:

Eastport Sentinel, Oct 19, 1859:

A veritable sea serpent was harpooned there (Lubec) by Captain Allen in 1829.—Its length was 38 feet, and its skin weighed 1,700 lbs. Our informant told us that it had 1,000 sharp teeth, which were not entirely in the place they ought to be but were like spike armor, all over the roof of the mouth. Its gills, when laid out, measured 120 feet, and resembled a coarse toothed comb. Its mouth was so wide that a hogshead could easily enter the distended jaws. The flukes of the tail were eight feet apart. Mr. Stephen Emerson bought a share in the dead “critter” for three doubloons and guaranteed in addition to furnish two horses and a wagon for the purpose of exhibition. But just after this Sea-monster in his prepared state left Calais, Mr. Emerson, thinking that it might not be such a serpent as Pantoppider saw in Norway, and Nahanters saw in Boston harbor, went to J. Shephard Pike, in Calais and asked him to explain the nature of the leviathan. Mr. Pike, not being at that time as old as he is now and never having a naturalist education and tastes of Prof. Agassiz, had resort to the Encyclopedia, and pronounced the sea-serpent a huge basking shark. Mr. Emerson profiting by this information sold out his share in the concern for S500.

In fact, both the 1829 and 1868 fish and a third described below by the Sentinel on August 10, 1870 were likely relatives of the unattractive fish above. From the Sentinel 1870:

Last Friday a large shark over 29 feet long was discovered in a weir at Lubec. It managed to [stay] away from the weir and steered for deep water in the “Narrows” where he was attacked by a number of men in boats who captured and killed him after a hard fight.

The Lubec correspondent of the Machias Union said that capturing and killing the shark made quite an excitement among the people. Large numbers gathered on the wharves and beach on both sides of the Narrows to witness the skill of the boatmen throwing lances, harpoons and bowie knives into this leviathan. Messrs. Staples & Gillis bought up the shares. The skin was sold to Messrs. J. & S. Griffin of Eastport. A large number of people visited the fish Saturday. This fish is said to resemble the large shark captured at the Carrying Place two years ago. It measured 28 feet in circumference.

All were confirmed to be basking sharks, pictured above, which, while normally about 20 feet long, can grow to nearly 40 feet, every inch of which is totally harmless to humans as the basking shark is a filter feeder eating nothing but plankton. This explains the large mouth. The basking shark is second only to the whale shark as the largest fish in the ocean.

Still, the rarity of shark attacks Downeast does not mean the shark has no place in our history. In addition to the appearance of the occasional basking shark and great white, the Gulf of Maine is home to the spiny dog fish, blue shark, shortfin mako, porbeagle, thresher and sand tiger shark. George Boardman, our noted 19th century naturalist, studied local sharks and was eager to get a specimen of a basking shark to send to the Smithsonian but could never find one small enough to ship. In addition, Downeasters, being mariners of some note, had numerous encounters with sharks on sea voyages, some of which ended badly. From a Robbinston history by Harriett Burke:

Every town has its local history and folk heroes. One of the more interesting stories that has circulated around town is the story of Bill Johnson, a “blue-water” sailor. Bill was long overdue from one of his voyages and the people of Robbinston had given him up for lost. He was also known for his tall tales. He finally returned, scarred and darkened from his voyage. Bill claimed he had fallen overboard and had fought a shark to save his life. People considered this another of his stories. Years later a citizen of Robbinston was eating at a New York waterfront restaurant and met a friendly sailor. Finding that the Mainer was from Robbinston, he asked him if he knew “Sharky” Bill. It seems the sailor had been in the South Pacific when Bill had fallen overboard and had witnessed the event. “Bill had been so badly hurt they left him at the nearest port.” Bill died with the people of Robbinston disbelieving his story.

Another local story describes the sad fate of a St. Andrews man who sailed out of Calais:

The accompanying article from the ‘Boston Herald’ has been sent to St. Andrews friends of John GALLAGHER s/o late Frank GALLAGHER. Mr. Gallagher, who had been sailing out of Calais, Me. for some years, not long ago went South and his friends fear the appended story tells all too truly of the horrible end he must have met.

Palm Beach, Florida, April 11, 1896 – Azel Johnson, one of the crew of the schooner “Seminole”, floated ashore at Palm Beach on a piece of wreckage Wednesday and was carried at once to the house of refuge at Fort Pierce. Johnson was half mad from hunger and thirst and is now being tenderly nursed back to life. He is delirious at times, but from his incoherent story, he must have had a harrowing experience. Five days and six nights he was without a morsel of food or a drop of water. The schooner was struck by a squall and carried on her beam ends. The men did not have time to launch the boats but grasped what was nearest to them. Johnson and two companions, Jack GALLAGHER and W. WHITE, secured a place on the deck cargo of lumber, which had shifted into the water. Johnson says he believes the captain and four others were drowned. After three days of floating under a scorching sun, Gallagher, tortured by thirst and against the advice of his companions, drank his fill of salt water. He was soon seized by a terrible itching. He grew weaker and weaker, all the while raving like a maniac and pointed to the huge sharks that silently followed the craft, watching with their beady eyes every movement of the men. Finally, Gallagher with a cry of despair sprang out overboard. Only half of his body arose to the surface and his face was distorted in horrible agony as the sharks tore him in twain. The terrible experience preyed upon the mind of White and next day nothing could restrain him from following his mate. He sprang into the sea and was also devoured. Five ships were sighted but Johnson’s efforts to attack [sic] their attention were in vain. At one time he stood on the raft and tried to shout, but his tongue cleaved to the roof of his mouth. The sharks still followed and several times he was tempted in his delirium to throw himself overboard, but when he started to do so, he said he would hear what seemed like the sound of a church bell. Then he imagined he was near shore. Finally, he sank into unconsciousness and it was while he was in that state that the raft floated into the Gulf Stream which swings and touches Palm Beach. Here at last the poor sailor found succor.

Our nautical history contains many such tales for sharks were greatly feared by our sailors especially in the warmer climes. Even our soldiers were victims of sharks. During the Civil War a Eastport soldier named Charles Preston and two other soldiers were drowned after an encounter with sharks while swimming in warm Southern waters.

Tales of sharks and their ferocity were standard fare in the old Downeast papers, both in news reports and the fiction for which many readers who cared little for news or politics bought the papers. Even humorous anecdotes about sharks appeared in the local papers. The Sentinel of 1899 reports what we presume was a fictional exchange between a northern local and a Florida lady:

Lady: “I should dearly love to go sailing but it looks dangerous. Do people drown often in this bay?”

Local: “No, indeed, mum. Sharks never let anybody drown.”

On other occasions snippets provided food for dark thoughts such as when the July 19, 1871 Sentinel reported that a shark caught off Charleston, South Carolina had a pair of boots, a scalp, two CANNON BALLS and a package of Sunday School tickets in its stomach.

Finally, we close with this February 19, 1904 article in the Eastport Sentinel which happened to turn up in our records search for the word “shark.” Other than “Shark” being the name of the early submarine, the piece has nothing whatever to do with sharks, but the experiment, firing dogs from a sub’s torpedo tube, is so bizarre we simply had to share it.

The experiment of firing dogs through the tube was made on the submarine boat Shark in Narragansett bay. Two large animals were used for the test. One at a time they were placed in the tube and a block of wood inserted behind them to make the “charge” fit snugly. The animals and the block were then expelled precisely as if they had been torpedoes. It was thought by some naval officers that the force of the compressed air charge would kill the dogs, but after their violent exits from the tubes they promptly arose to the surface and began swimming around as if nothing had happened. They were picked up and taken to the station, where they are now capering around as lively as ever. A reporter who called at the New York office of the Holland torpedo boat company, which designed the nine submarine craft that the United States has in commission, was told by the manager that it would be perfectly practicable to expel men without injury from the torpedo tubes, just as the dogs had been “ fired out.” Previous to the Narragansett bay test, he said, a dog had been discharged from the tube of a submarine boat at Annapolis, and this animal also escaped injury, except that his feelings seem to have been badly hurt, for after rising to the surface and swimming ashore, he lit out for the next county, and may be running yet for all that anyone knows.