A hundred years ago someone wanting to get a quick message to friends and family would send them a penny postcard. Dozens of local shops sold postcards and Miss Jackson of St. Stephen had a store on Water Street devoted almost entirely to an inventory of hundreds of postcards. Most postcards offered “Greetings” from your town, but the scenes were generic. If anyone can identify the Alexander scene above, we’d be very surprised; and the scene of sheep grazing contentedly along the river is almost certainly not in the St. Croix Valley. It’s not that people didn’t raise sheep in this area—wool was a necessity in the early days; but if folks hadn’t required wool to make clothing it’s unlikely many would have bothered keeping sheep. The postcard reminded us of an interesting story about a “sheep drive” through Calais in 1870.

Much of the allure and romance of the old west centered on the cowboy and the great cattle drives from Texas and Oklahoma to the rail junctions in Kansas and Missouri. Calais unfortunately lacked most of the requirements for a successful cattle drive, cattle don’t thrive well in hilly terrain on the forage provided by thin, rocky glacial soil. However, in 1870 a man arrived by boat in St. Stephen with a flock of 712 sheep he had purchased in Prince Edward Island.

He drove the flock from St. Stephen across the old covered bridge at Ferry Point, pictured above, to Calais, through town and down the county road to Machias where they were loaded on boats bound for Portland. We suspect some of these sheep took up residence in Calais, Robbinston, and other towns along the great Northeast sheep driving trail, although this may have been the only “sheep drive” along the trail. We do wonder if the owner was assessed the costs of cleaning up Main Street in Calais after the drive. If you’re suspicious about the “sheep drive” photo above we do confess the mountains in the background resemble neither Chamcook or Maguerrewock; but we thought it would give the reader the general idea of how easy it is to drive sheep. As to why the sheep weren’t shipped directly from PEI to Portland, we can only suggest it had something to do with strict British tariffs, export laws and prohibitions on shipping from most colonial ports directly to the United States. As it was nearly impossible to use the customary procedure of smuggling the sheep over the line the owner paid the ½ cent a head toll to bring them across the bridge into Calais after perhaps greasing the palms of a few customs officials on both sides of the border.

The only other mention we have of a sheep drives in this area comes from John Dudley’s history of the Airline:

DROVERS – I would note here that this east-west road was used starting with the Civil War to transport livestock on hoof. During the War, horses from the Maritime Provinces for the Union Army were driven west. Later droves of cattle and sheep moved in whichever direction economics dictated. From the Machias Union of October 18, 1898 – Wesley: “Ferren & Son, drovers from West Levant, left this town last week with over 80 head of cattle.” (S. H. & C. T. Ferren). An unpublished account tells of Lincoln Flood and several other men from Alexander driving a flock of sheep across the Airline to Bangor. At one house they stopped for a meal, and the men had to share one spoon and one knife.

The raising of sheep was somewhat of an ordeal for the early inhabitants of the St. Croix Valley, but cloth had to be woven and clothes made.

Hayden Diary Robbinston – April 7, 1853: “Mrs Delpha Boyden sent home the cloth she had wove for us from our wool by Charles and James. She had a settlement to make with us for weaving and finding the warp.”

And sheep were often the favorite pets of farm children like these boys from Pembroke. In St. Stephen historian Doug Dougherty tells us:

(1898) Mr. Bell, who lived on Prince William Street, owned a black sheep called “Flip”. The sheep had a habit of visiting the neighbors in the vicinity and one morning entered a home, trotted upstairs, and appeared before a young lady who was in one of the bedrooms. The young lady became frightened, as she was not accustomed to this type of visitor.

Unfortunately, sheep were nearly defenseless against predators. Dogs were especially a problem. One large sheep farmer in Pembroke threw in the towel and sold his entire flock after dogs had killed nearly 20 of his sheep in the space of three days. Bear could also decimate a flock although sometimes it was the bear’s last meal. From Murchie’s history:

At Digdeguash another plucky woman, wife of William Stewart, kept sheep to provide wool for her handloom. One day a bear appeared. She drove the sheep into the little potato cellar under her cabin. The bear followed and all the sheep ran out but one. To block the bear in the cellar she piled stumps against the cellar door. The cabin floor was made of poles. The bear tried to get out by climbing through the floor into the room above. So, Mrs. Stewart seized an axe and hacked at his paws. Although the enraged bear ate the lone sheep, he was shot when her husband came home.

According to Feed Keene of Red Beach sheep did have some utility beyond their wool and meat:

The old attic was full of these and other things sometimes to me unknown, but which were dragged out when I came home sniffling, after a drop through the ice at the opening of the skating season. There were dried and ground pumpkin seeds, said to be death to pin-worms and a vile, last resort concoction, derived from the sheep pasture, known as “nanny tea” for driving out the measles, or mumps, I forget which (I took it for both) and survived but cannot yet look a sheep in the face.

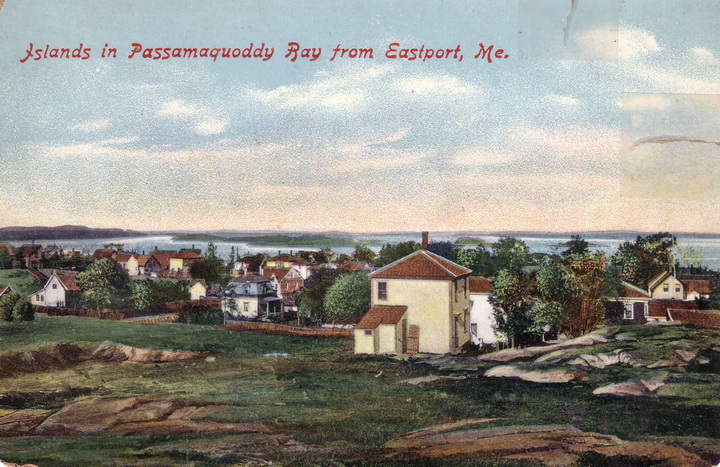

It came as somewhat of a surprise to us to learn that the folks in Eastport had a special breed of sheep-or so they claimed. Eastport’s “Island” sheep were pastured year-round on the many uninhabited islands in the bay and left to fend for themselves even in the winter. The situation caught the attention of the Portland Society for the Protection of Animals in 1900 and the Eastport Sentinel reported as follows:

The Portland Society for the Protection of Animals have been carefully looking into the subject of the sheep which are wintered on the islands of the Maine coast.

A report was made at a meeting of the society the other day by John McManus of South Portland, who visited the islands along the coast for the society and investigated the condition of affairs. The society voted at the conclusion of the reading of the above report that the owners of sheep on those islands where the animals are not properly provided with food, water and shelter, must move them by the middle of December or they will be prosecuted by the society. The owners of sheep on such islands will be notified in a formal manner and through the newspapers, and if they don’t take warning will be prosecuted.

Apparently the owners did not “take warning” because the threatened notice was published a few weeks later followed by lengthy letters in the Sentinel from the sheep owners explaining that the “Island” sheep had somehow become a special breed of sheep, adapted to the climate, happy without shelter, perfectly content to live on seaweed during the winter and even preferring snow to water since the owners made no provision for watering the animals during the long winters. The dispute dragged on into 1901, but if it was ever resolved the outcome was not reported in the Sentinel.

Finally, sheep or the lack thereof were useful to a town trying to reduce its county tax. In the category of “Some things never change” we recently came across a petition filed with the Court of Common Pleas in Machias dated March 17, 1791 by the residents of Calais when it was still Plantation 5. In the petition the residents strongly protested the outrageous amount of the “county tax” which was then being demanded of Calais to fund the operation of the county government. The petition pointed out that Plantation 4 (Robbinston) with a population of 55 to Calais’ 59 and having “more property and better privileges” paid less than half the tax of Calais. The strongest argument for the abatement, however, was wolves: “The wolves has destroyed dubble the number of sheep and cattle (or near it) in this Plantation to any other Plantation in the County, therefore, we find ourselves very unable to pay our taxes was they in proportion but are much more unable to pay a double proportion.” Mike Ellis, the Calais City manager, should take note of this petition when he fights his annual battle with the county. After being overtaxed by the county for 230 years Calais deserves a break, especially as we don’t believe there is a sheep left in town.