Nathaniel “Nat” Barker was born January 27, 1878 and grew up in Dresden, Maine. He was a good student and worked in his father’s ice business on the Kennebec River. The work of cutting ice and loading it onto ships for transport was not well paid- $1.50 a day- even if the boss was your father so Nat decided in 1902 to attend medical school at Bowdoin. He graduated in the summer of 1905 and, being single and adventurous by nature, he readily accepted the offer of a six month contract to work in a wilderness town in Downeast Maine. A group of investors was building a paper mill at a place called Sprague’s Falls and needed a doctor to tend to the hundreds of workers, mostly immigrants, who were building the mill. The fact that Nat had just finished medical school and had no experience wasn’t, apparently, a concern. Possibly no established doctor would take the job and Nat himself might have had second thoughts had he known how primitive were to be his living conditions and demanding his practice

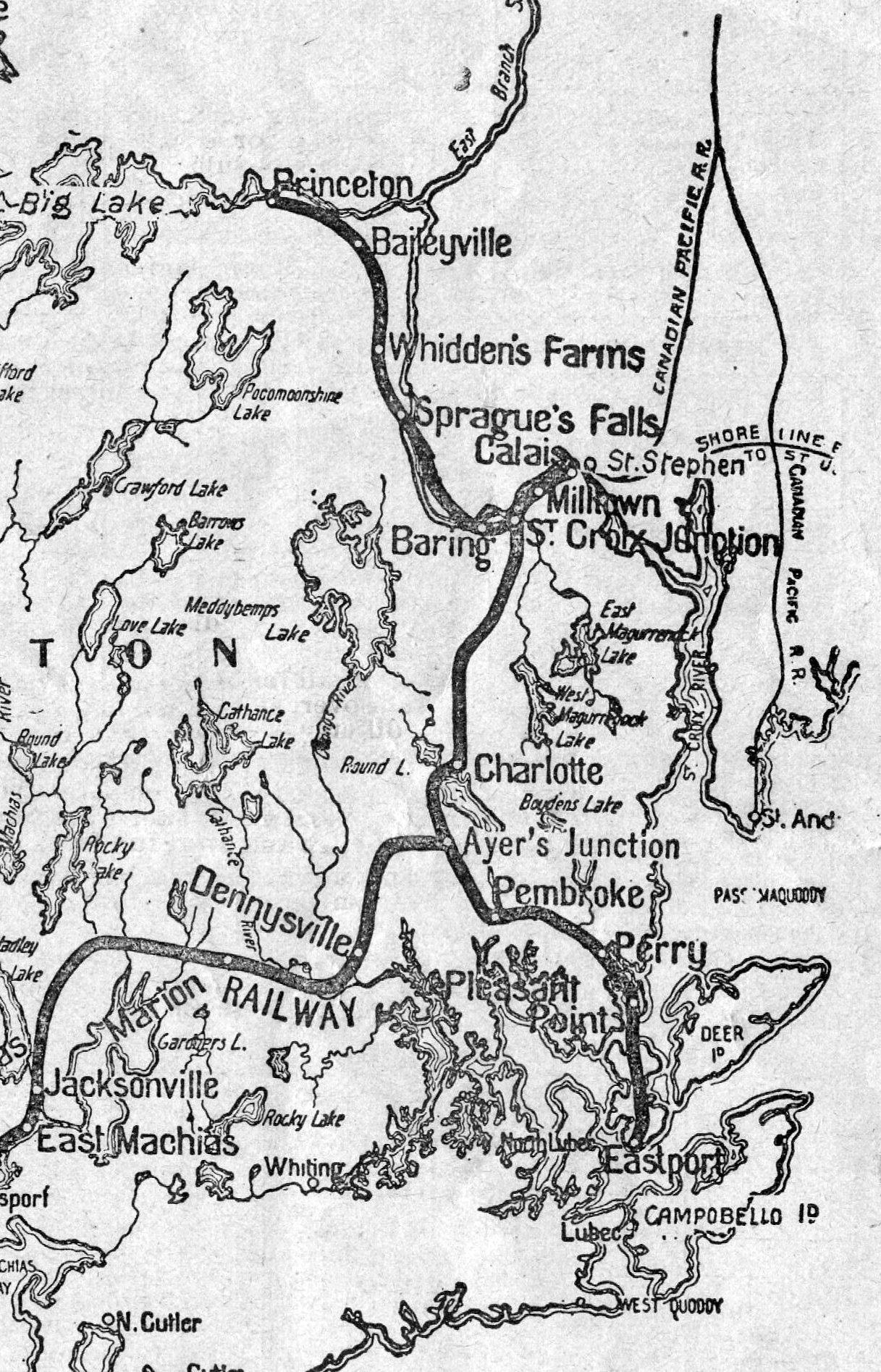

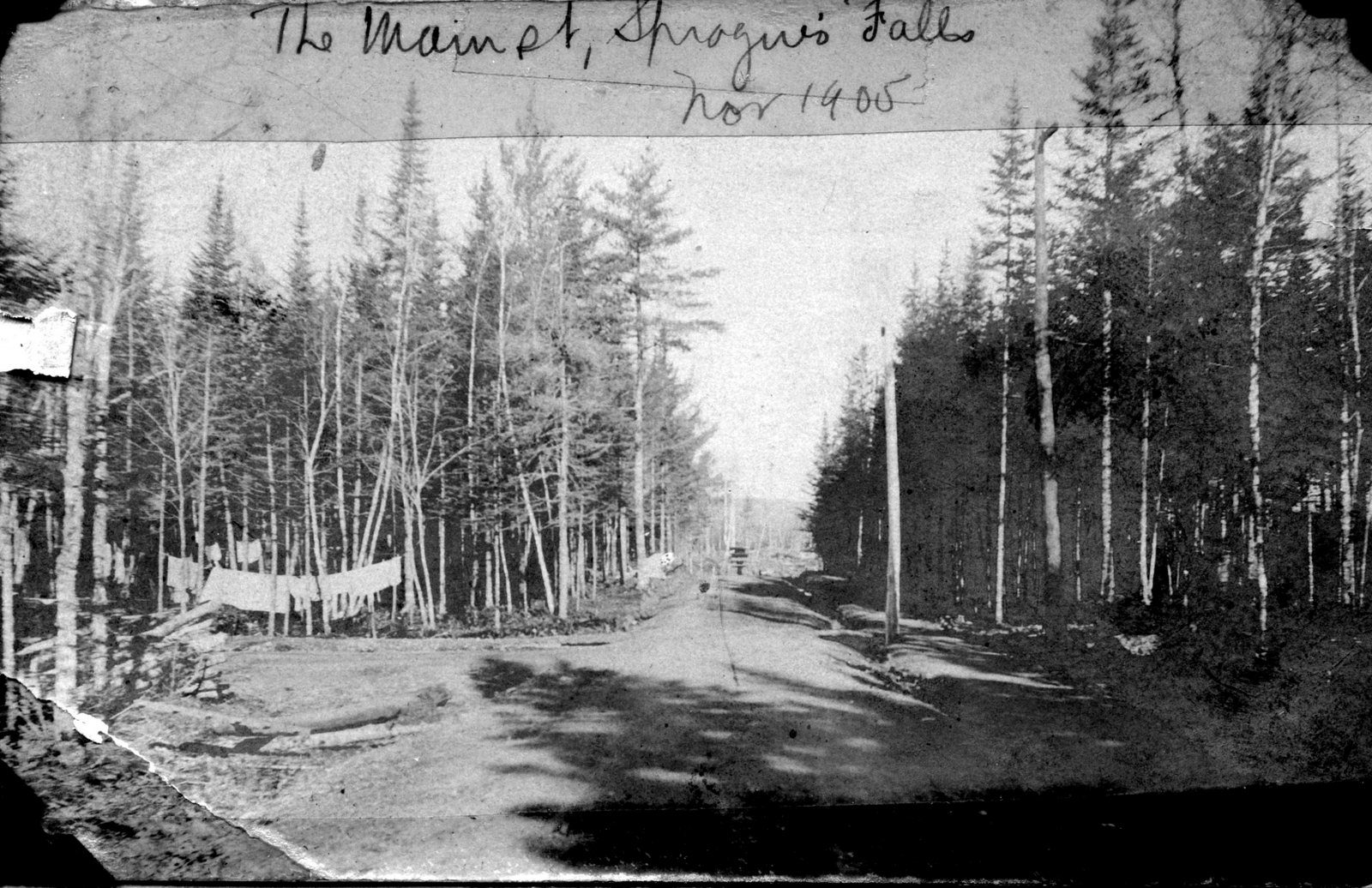

In November 1905, a few months after Nat had arrived at Sprague’s Falls he took the above photo of the Main and about only street in what would become the village of Woodland. Most of very old photos below are from Dr. Barker’s personal collection and are now preserved at the Baileyville Library. The town was officially and legally Baileyville but the actual settlement of Baileyville was two train stops up the line as shown by the railroad map above. The settlement of Baileyville was closer to Princeton than to Sprague’s Falls. Sprague’s Falls was just one of three stops on the railroad in the Town of Baileyville but it had the advantage of being situated where the river’s elevation dropped 25 feet in a short distance. It was a perfect spot to dam the river and provide power for a paper mill. Paper was much in demand in those days, especially for newspapers which had become very popular. In the late 1800’s Calais had two newspapers, one a daily for a short period, Milltown had its own weekly called the Homestead and even Forest City residents could look forward to reading the news in the Forest City Advance. Danforthers eagerly awaited the next edition of the Danforth Border News. Local businessmen with connections to big city money felt a mill at Sprague’s Falls would be a very profitable venture. They were not mistaken.

According to Dr. Barker

I arrived on June 27, 1905. Was greeted by ‘Pomp’ Sylvester who was depot agent in a box car. Seven of us lived in the old St. Croix office shack. Beginning a new hamlet was very crude. Men lived in tar paper shacks and brush huts. Food was scarce and cheap, board was $3.50 a week.

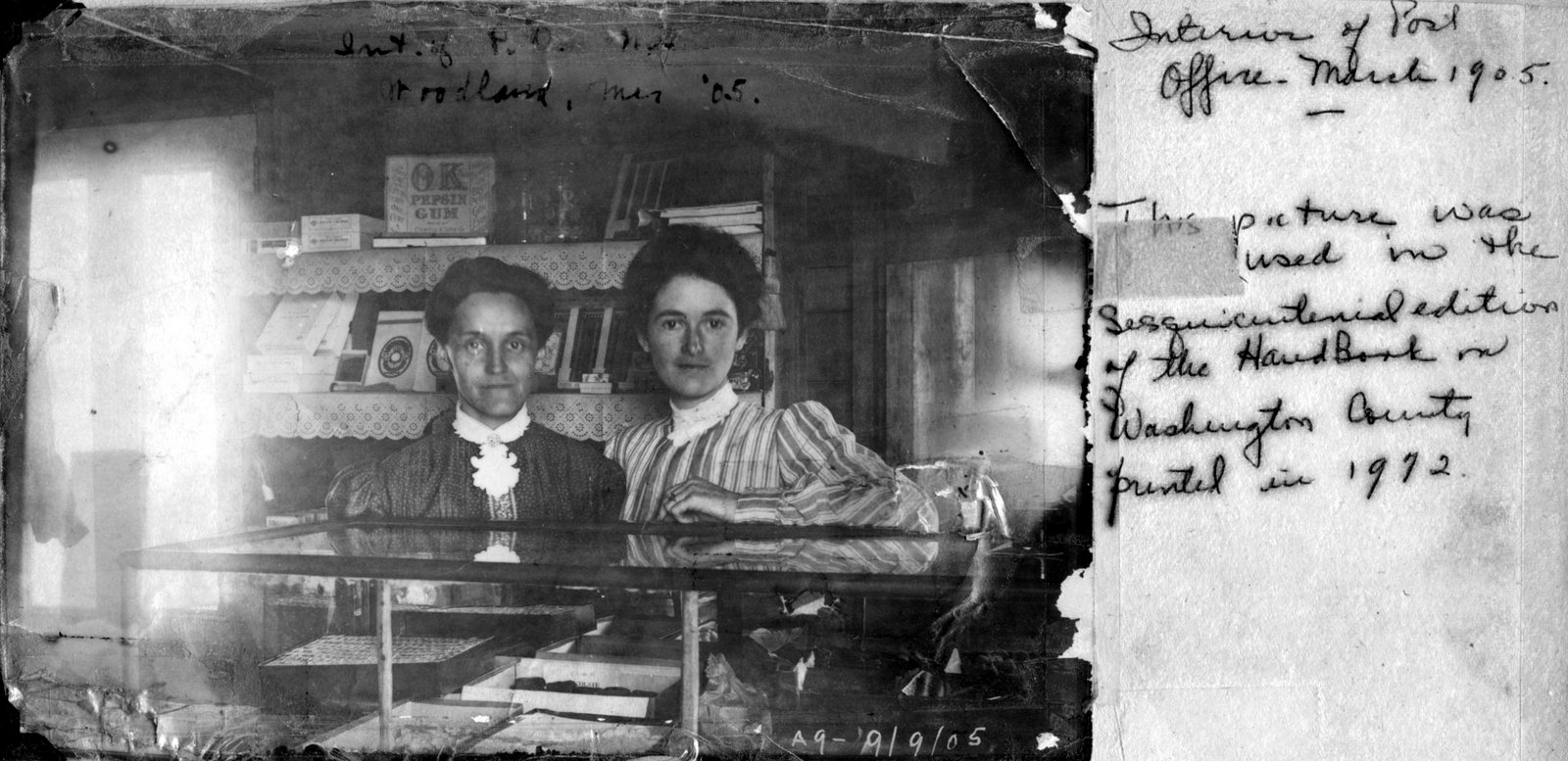

Although the surroundings were primitive, the town was not entirely without services- there was a Post Office, built elsewhere and hauled to the Falls on a flatcar which made it perhaps the most solid building in the new town. The clerks were two ladies who must have been very lonely for female companionship in the Sprague’s Falls of 1905- the thousand or so other residents were almost entirely foreign contract laborers.

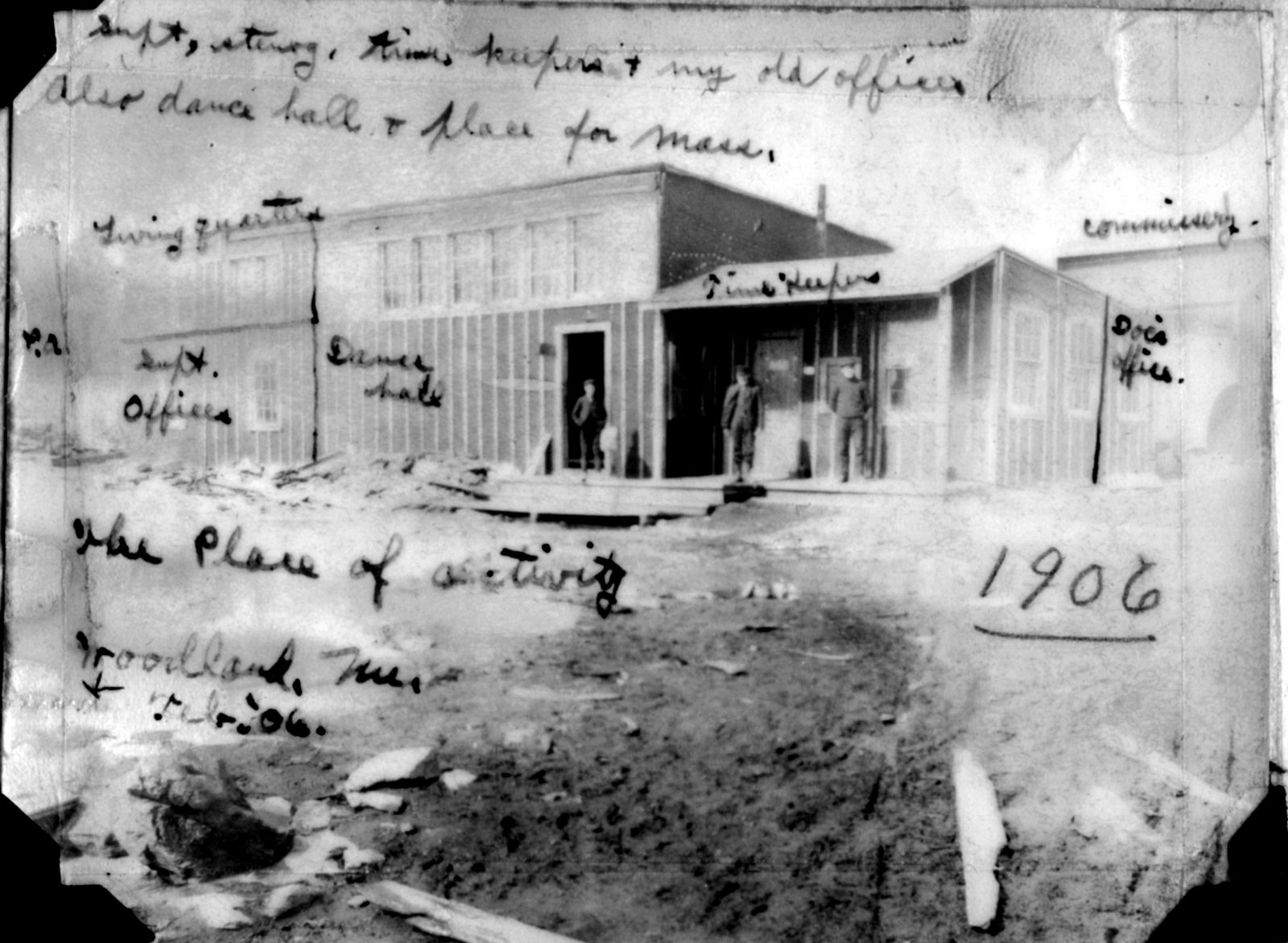

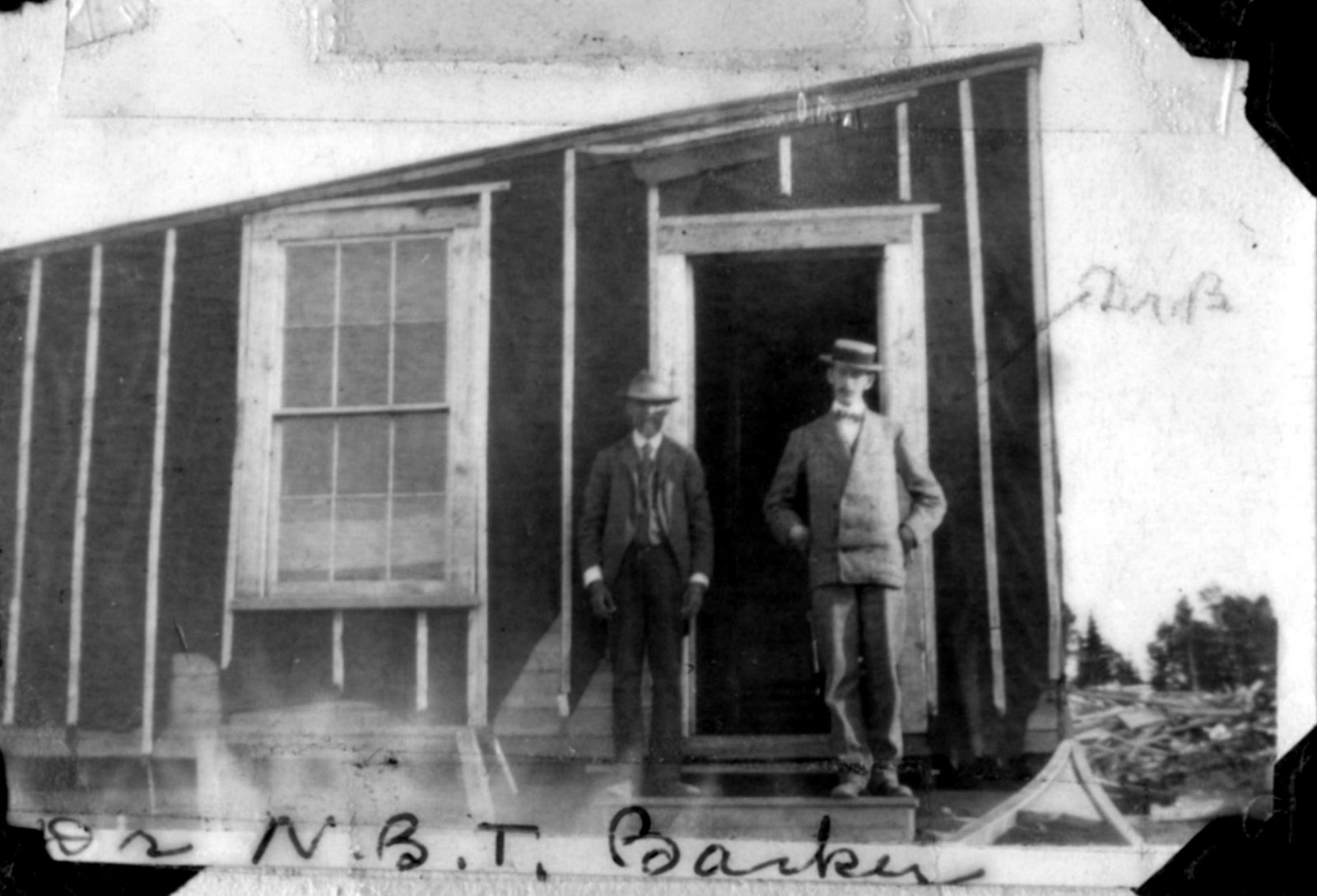

City center in 1905 and early 1906 was a clutch of rudely constructed buildings shown in the photo above. The Superintendent’s office, time keepers office, living quarters for the staff including Dr. Barker and a commissary were about the extent of the “board built” buildings. Dr. Barker’s office was in this complex as was a dance hall and “place for mass” for the hundreds of Italian workers. Dr. Barker and 6 others bunked in the sleeping quarters along with thousands of bedbugs. The doctor recalls using a pin to stab twenty five of the pests who were sharing his pillow one sleepless night. The workers lived in even less wholesome circumstances.

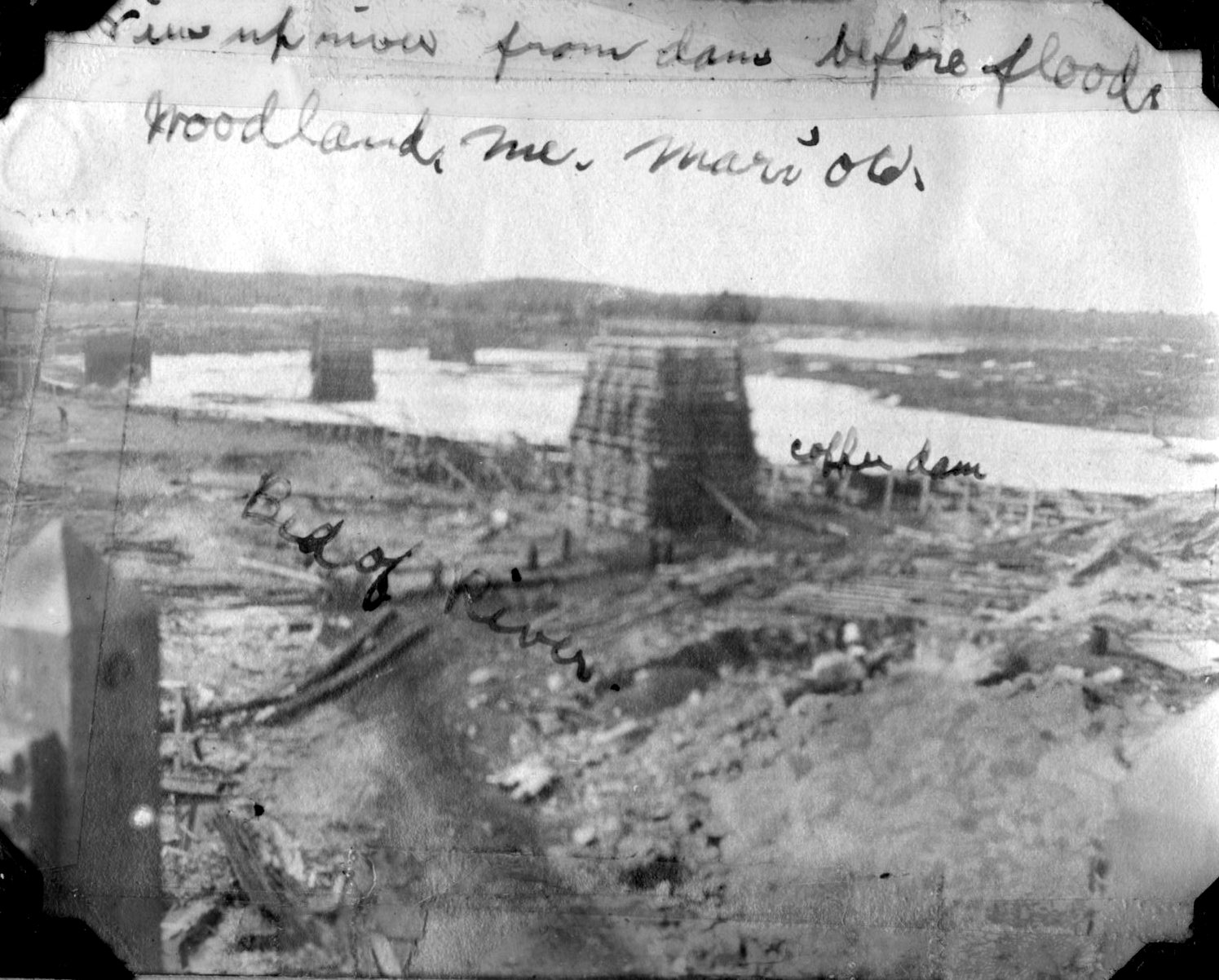

One of the first jobs of these workers was to build the coffer dam seen in the photo above, diverting the river so the mill dam could be built. Dr. Barker has noted on the photo “Bed of River” which shows the natural course of the St Croix. When the coffer dam was breached after the mill dam was finished the river resumed its natural course and this area became the mill pond. The pier in the photo was then almost entirely submerged and Dr. Barker’s office had to move to higher ground.

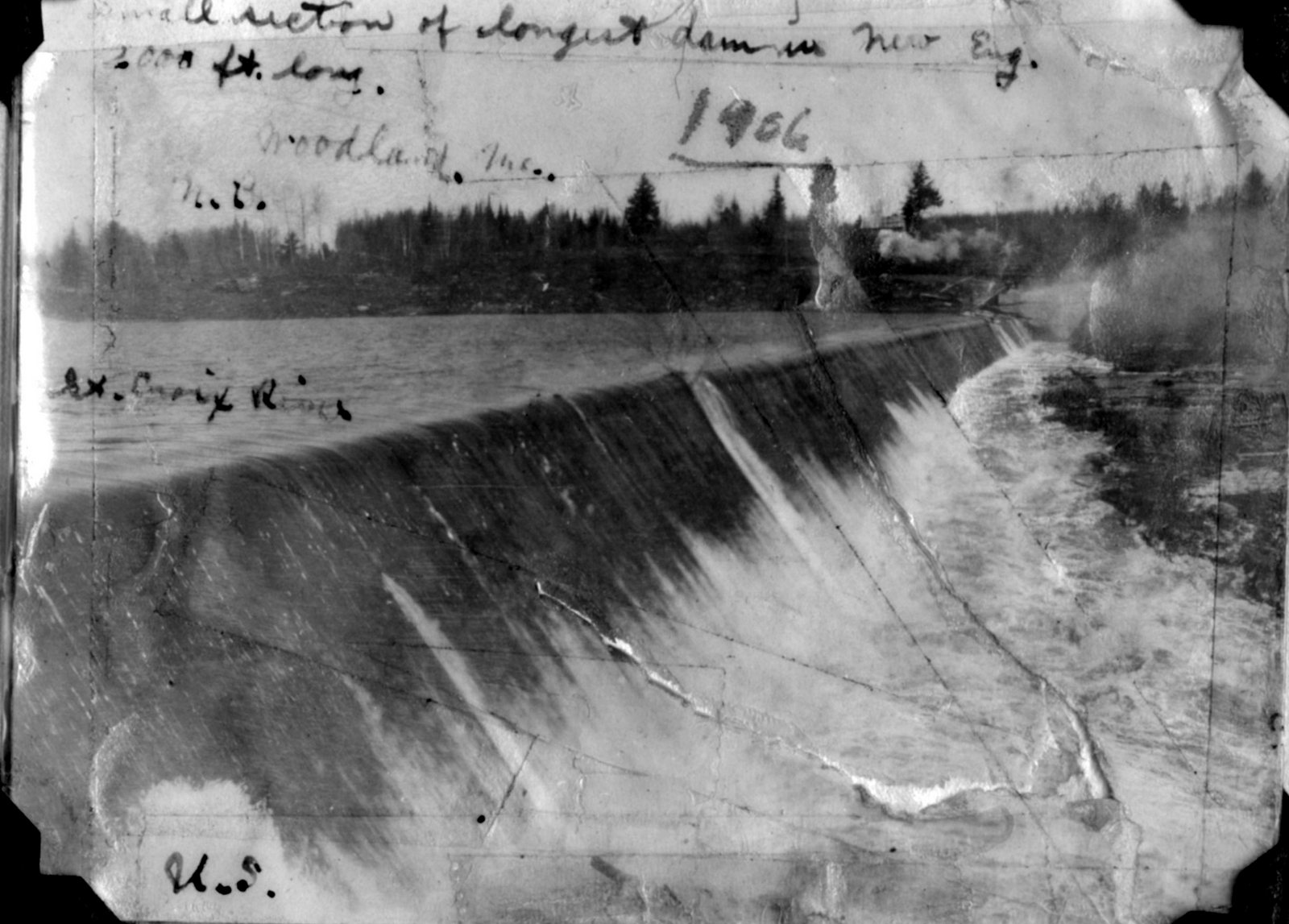

The dam itself was 2000 feet long and the longest in New England at the time.

The dam itself was 2000 feet long and the longest in New England at the time.

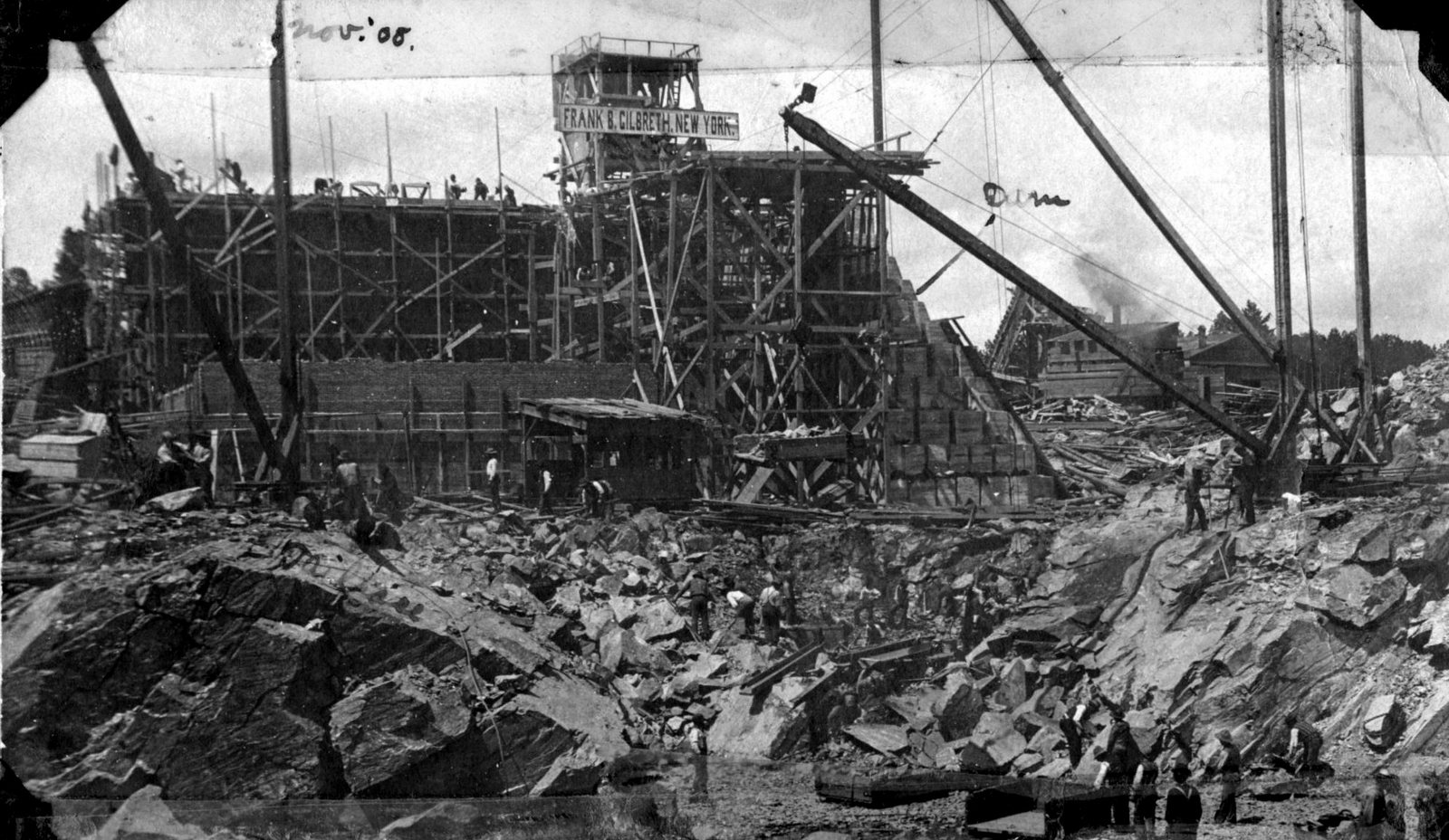

After building the dam the workers began construction of the mill itself seen above already partially completed in November of 1905.

The workers lived rough, often in sod and pole huts, like one pictured above right. Dr. Barker’s note on the photo describes the sod hut as “ Which the first comers lived”. To the left above is a tar papered building which Dr. Barker, standing at the center of photo, describes as “Modern House”. Perhaps he was making house calls that day. The “Modern House” seems to be occupied by a family and it is likely some of the immigrants were accompanied by their families given the number of children the doctor delivered during those early years.

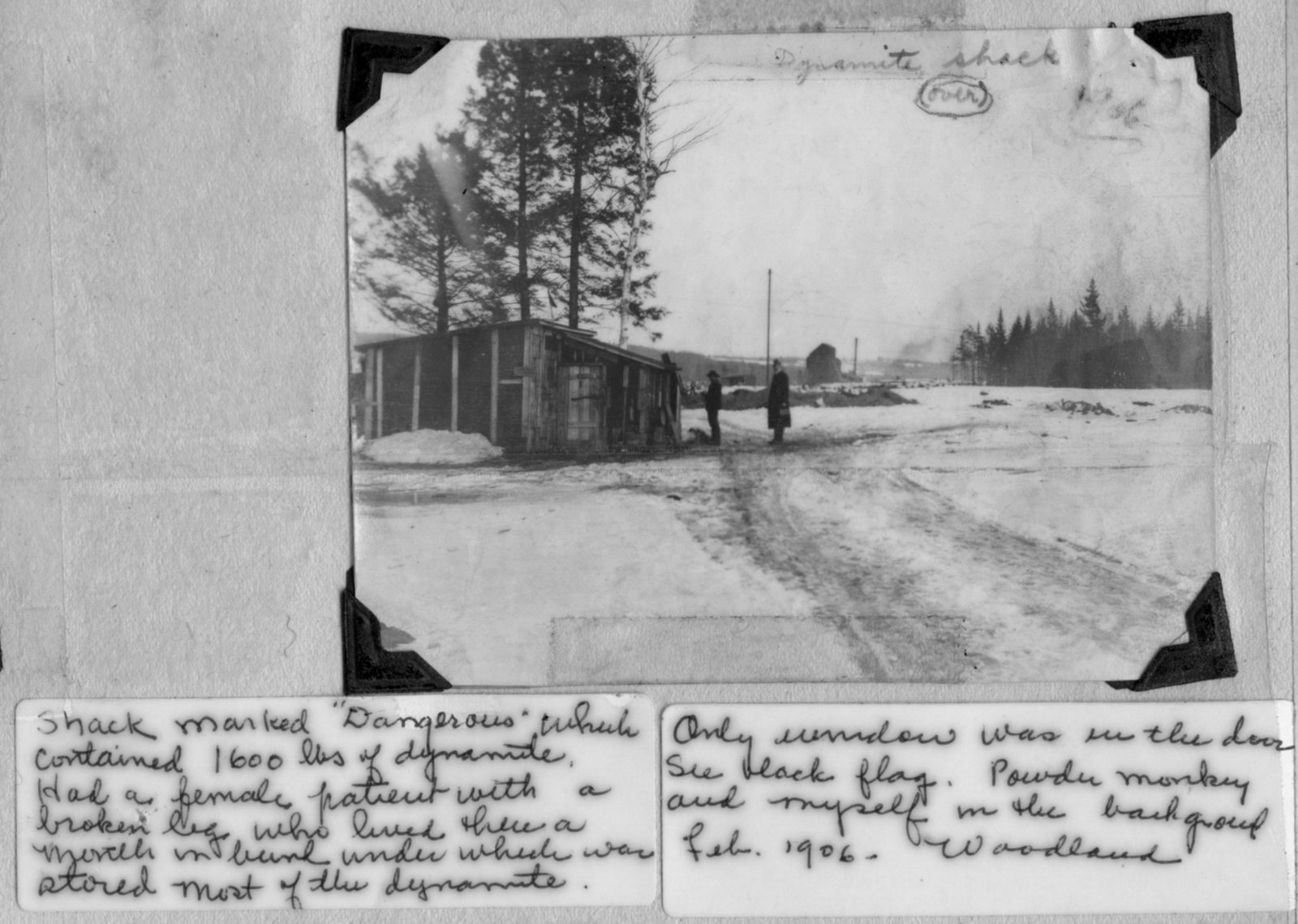

When it got too crowded in town there was always the bunk in the dynamite shack which for some reason always seemed available.

Dr Barker’s office was called the “Life Saving Station” and it was certainly that and more. His six month contract was either officially or unofficially extended indefinitely and he eventually met a young school teacher in the new town and married. He did not leave for 21 years and during his time as Woodland’s doctor his experiences were unique in many ways. In addition to doctoring Dr Barker was often the mortician, family counselor and graveside minister. He reminisced about his years in Woodland in a letter written in the 1936:

I attended, in my 21 years there, nearly 1,000 confinements numbering about 12 nationalities. One was a Gypsy Queen, on some straw and a horse blanket, in a tent on a cold December day. Another, an Indian woman, another a Belgian girl, then came Italian, Hungarian, Scandinavian, French, etc., Mrs. John Topolosky recently told my wife that we both attended 150 Austrian and Hungarian cases. Old Mrs. Guilfoyle – that kindly and genial soul, with the Irish wit and humor — assisted me with many cases. Also Mrs. Chas. Wright, (latter two now deceased.)

First sick child I attended was Frankie Lydic, then a puking baby. First three years many cases of small-pox, diphtheria, typhoid and scarlet fever, mostly severe cases. One case of small-pox and diphtheria each, I laid out, buried and read the burial services, assisted by my faithful friend ole Bob Preston. Usually gave him a bottle of whiskey (price then $1.25) to assuage his grief, and mine too. My first pneumonia case, a laborer, in a tar-paper stable of 27 horses, Jan. 1906. Cold, temperature 10°, no stove. He was in an empty stall, very cold days but horses kept him warm at night. Kept on his cap, mittens, and boots all the time. I took him in soup 3 times daily. He got well – survival of the strong and the DIRT.

Most of us had bedbugs the first two years, then a sign of democracy.

One busy day on construction I attended 27 accidents. In 21 years over 25,000 cases of accidents, big and little. Several men were killed on the job and in the mill. Used to pick up the remains of some in baskets. One morning we found Chief Joe LaCoute, an Indian, 85 years old, frozen stiff in his wigwam.

An amusing item: One day, an undersized Italian came to see me, in severe paid (colic) saying: ‘Poor Tony, me seek at de bel, seek at de gut, me eet “big eye chick.” On further inquiry I found that someone had given him a dead owl, which he had cooked and eaten.

During my sojourn I had vaccinated 96% of all the children, big and little, against small-pox. The State Dept. of Health stated that was the best record in Maine.

In 1906 Fred Newman smashed his big toe. It took George Kent and four other men to hold him down while I sawed off the toe. About 1 pint of gin was the favorite anesthetic given at that time. Of course that went well on top of a hearty dinner.

I had substituting for me, when on vacation, about 25 different doctors, mostly young men. They obtained a greater variety of practice there than any place. It was almost thrown at them.

Thomas McCormick, the first Gen. Mgr., of St. Croix came into my room at hotel late one night and died in my bed. My first experience assisting in embalming. He was a generous, and splendid man.

In my repertoire of patients was a huge rattlesnake, which a snake-charmer brought to my bedroom one night. It glided beneath my bed while I stood on the bed. Several horses badly cut, whom I sewed, one cow having a calf, which I assisted, (a difficult case in the country) cats and dogs galore.

Many cases of domestic trouble, pathos and comedy intermingled, where I was called upon to act as the peace¬maker.

A sad case 29 years ago: a nine year old girl died of black diphtheria. I put her in a casket, fastened the lid while Rev. Butterfield, outside the door, (no one allowed in) read the burial service. Then I placed tire casket in a cart, which Bob Preston drove to the cemetery. As the brief services were read, the mother, whose bed was near the casket, gave birth to a baby, which I attended (as doctor and nurse). LIFE and DEATH. Husband had left town.

I have personally washed over 150 babies. Prefer the Italian and Hungarian method: Drop the kid in a tub of hot water and use yellow soap — removes slime best. Far ahead of American way of bathing.

Another baby case: A few hours later the baby’s face was like a piece of beef-steak, so badly bitten by scores of bedbugs. Personally, I did not get rid of them myself for two months. One night I stabbed 15 on my pillow with a hat pin. Ask Lucy Rogers – she was at the hotel then.

During the flu epidemic in 1918, (while working day and night for a month till I was taken, very ill, to a hospital) one day and night (24 hour duty) I made 64 house calls plus one difficult confinement (Belgian) and two accidents. In all I finally collected the sum of $3.00.1 have always placed my services first of all. Money was a secondary consideration. Twelve years ago I attended 58 cases of typhoid fever, ten of whom died, mostly in hospital. This epidemic was uncalled for, but my advice and warnings were not heeded.

Many other tragic events I could relate but it would not do. On an old sun-dial was an inscription “I count only the sunny hours.” Likewise, being only a country doctor, I remember the brighter things in life.

“A rose for the living,

A wreath for the dead.”

Mrs. Weeks, I have given you these few items of my medical pioneering on the St. Croix, some 31 years ago. These are all facts.

Have baptized over 100 babies for their spiritual improvement.

Another tragic-comedy confinement case: An unwanted and unexpected baby (will say that 90% at least of babies are not wanted). Very sudden call to come’ quickly. “Mother” Guilfoyle was there alone with the young mother so I placed some of Hearst Sunday papers (comic supplement and adv.) beneath woman’s buttock to keep dry. After baby arrived we turned mother over to wash and lo and behold! The word WELCOME in red huge letters was printed across her backsides. Evidently an adv. of Welcome soap was next to the skin and the wet bed stenciled or transposed the letters to the skin (which came off in a couple of days.)

Kindly excuse the scribble, the errors, interruptions and delay.

Please give my sincere greetings to the Woman’s Club, likewise to George and yourself.

Very sincerely yours, Nat Barker.

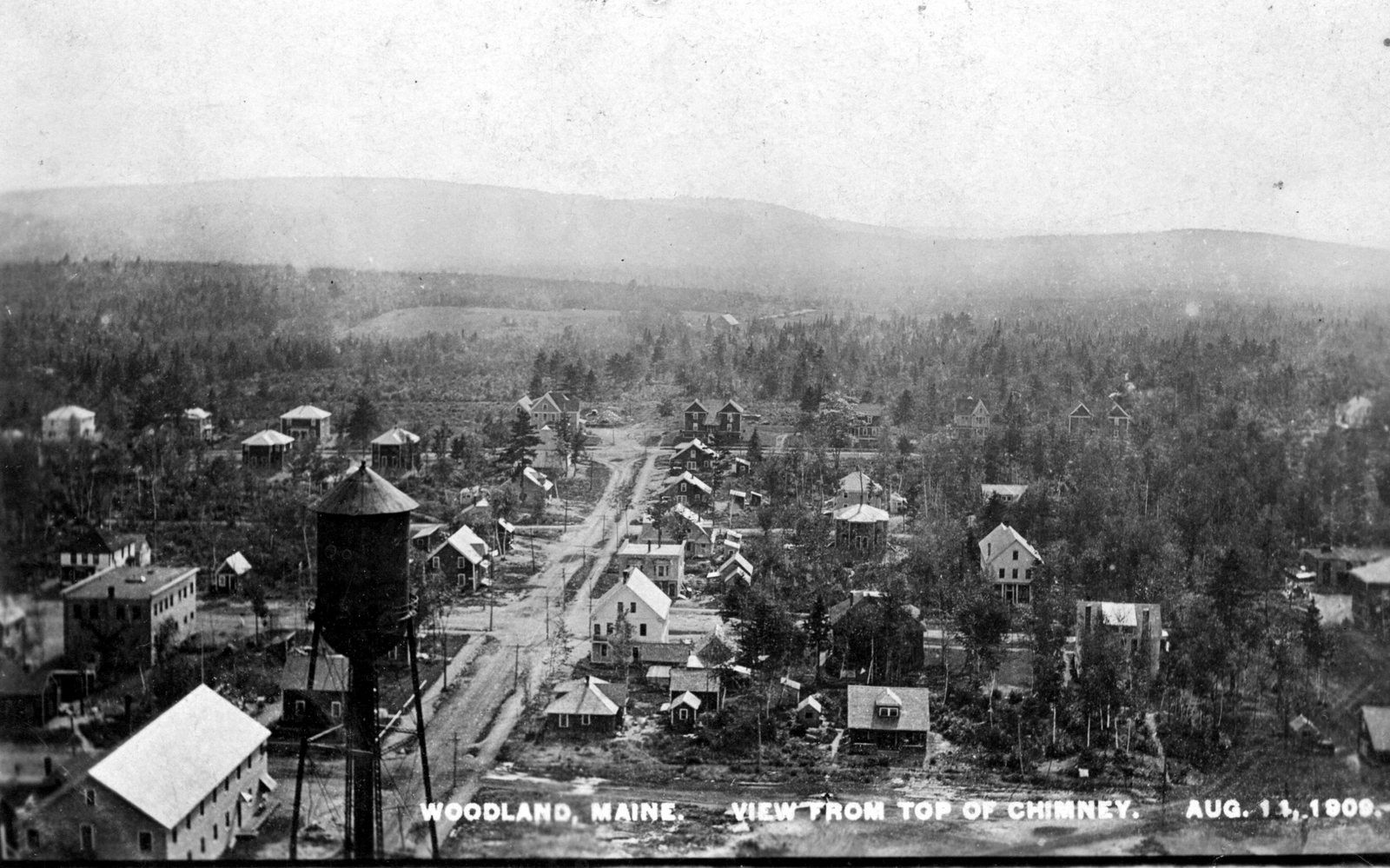

Woodland grew very quickly as the above 1909 photo shows, quite a contrast to the first photo taken by Dr. Barker in 1905.

The doctor was rewarded for his devotion to the town with a new office. According to Grace Ober’s history of Woodland:

“The Doctor’s next office was located on Main Street in what is now the parking lot for McCluskey’s. Later the little building was moved up to a lot beside the Woodland Inn. A waiting room and dentists’ offices were added, and to it all was connected to the old time office, painted and refurbished for a First Aid Room and doctor’s office. That location would be at the lower end of the Shopping Center Parking Lot designated for the Woodland Division Parking Lot.”

In 1910 the new Woodland school was dedicated to Dr. Barker. He served on the school board while living in Woodland and over the years became a beloved member of the community. After 21 years in Woodland he and his wife moved to Islesboro and eventually settled in Yarmouth where he was still actively practicing medicine at the age of 88. For many years he made a trip to Woodland each summer to visit friends and become acquainted with the many children he had brought into the world. Dr. Barker died in Portland Maine on June 8th 1967. He was 89 years old.