VANCEBORO-MCADAM RAILROAD BRIDGE 1915

“German Blows Up Canadian Bridge”

“Werner Van Horn seized in Maine after doing little damage, claims immunity”

“Canada ask extradition”

“Washington wonders if offense is political.”

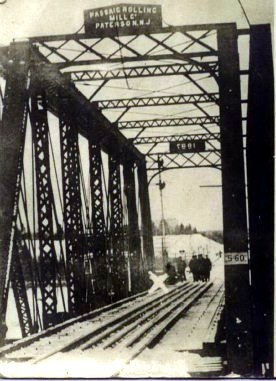

Such were the headlines in the New York Times on February 3rd, 1915 reporting the attempt by Werner Van Horn, an officer in the German Army, to dynamite the railroad bridge over the St Croix River between Vanceboro, Maine and McAdam, New Brunswick, a important link on the Grand Trunk railroad which fed war materials from Canada and the United States to the port of St. John New Brunswick. The bridge had been unguarded on the night of the attempt even though Lyman Holmes, our rail expert, says the destruction of the bridge would have seriously reduced the usefulness of the Port of St. John, a port which was crucial to supplying Allied armies in Europe. The Germans realized this, if the authorities in the US and Canada did not. The Canadian soldiers pictured above patrolling the bridge were only posted after Werner Horn’s attempt to dynamite the bridge in the early morning hours of February 2, 1915. He had been dispatched by German officials in New York to destroy the bridge and had it not been for the bitter cold on the night of the attempt and inaccurate information supplied Horn by his superiors, it might well have succeeded. It was one of the most famous acts of sabotage in this country during the First World War.

Lt. Horn, shown above, was an interesting fellow. About 33 years of age, he was patriotic, brave and surprisingly compassionate. He was not, however, according to those who subsequently interrogated him overly bright or trained in demolition. He had been 10 years in the German Army before being inactivated after which he moved in 1911 to Guatemala to manage a coffee plantation. He was reactivated when war between England and Germany was declared in August of 1914 and, obeying a general command from the German Army, tried unsuccessfully to return to Germany. He eventually reported to the German Consulate in New York where he was put in contact with the German military attaché in U.S., Captain Franz van Papen. Van Papen and his associates had orders from Berlin to arrange acts of sabotage within the U.S. to disrupt the Allied war effort in Europe and Lt. Horn fit perfectly into their plans. As the United States was still neutral in 1915, Lt. Horn could move freely throughout the country.

Vast quantities of military supplies and troops were moving along the Grand Trunk line from Canada and the U.S. through Maine to the port of St John New Brunswick. For the Germans one easily accessible weak link on this route was the railroad bridge at Vanceboro, Maine. Some thought had been given to destroying the Ferry Point bridge at Calais but it was determined this would have little effect on the movement of supplies. In New York Horn was given a suitcase of dynamite, a railroad map of eastern Maine and a ticket to Vanceboro where he arrived on January 30th, 1915. He checked into the Vanceboro Exchange Hotel run by Mr. Aubrey Tague but not before arousing the suspicion in the entire town and establishing beyond doubt his unfitness as a secret agent. Upon alighting from the train he was seen hiding his suitcase in a woodpile from whence he walked to the railroad bridge and conducted a very indiscreet surveillance.

Only after this did he retrieve his suitcase from the woodpile near the Vanceboro Railroad Station and check into the hotel where, being tipped off to his activities, Horn was soon interrogated by the chief U.S. customs officer in Vanceboro. He told the official he was at Dutchman looking to buy a farm in the area. Since the customs officer established Horn had not entered the country illegally, he decided he had “no jurisdiction” and dropped the matter.

Horn remained rather inconspicuous for the next day and on the evening of February 1, 1915, checked out of the hotel telling Mr. Tague, the owner, that he was going to take the 8 o’clock train. He hid in the woods until midnight but as the temperature that night was 30 below with a strong wind, he must have already been nearly frozen when, just after midnight, he started across the Vanceboro railroad bridge to the Canadian side at McAdam. Some reports claim he changed while waiting into his German army uniform to preclude any claim he was a spy for which hanging was the punishment. However this is unlikely. He waited until midnight because he had agreed to destroy the bridge only on the condition that no one would come to harm and van Papen had assured him no trains used the bridge from midnight to early morning. Halfway across the bridge he was surprised to hear a train whistle and, finding himself face to face with on oncoming train from the Canadian side, he leaped over the side and held onto the bridge supports until the train passed. This disconcerted him a good deal but he soldiered on, frozen and surely scared, only to hear a whistle behind him. Again he found himself in the path of a train coming from the U.S. side from which he again barely escaped. He now realized van Papen’s information about the Vanceboro train schedule was not correct or, more likely, a fabrication. This resulted in a change in Horn’s plans.

In addition to 60 lbs of dynamite,Lt. Horn had a 50 minute fuse. The 50 minute fuse was intended to allow Horn enough time to escape Vanceboro before the explosion. Horn intended to light the fuse and walk through the night the short distance, or so it appeared on his railroad map, to Princeton to catch the morning train and effect his escape. Horn had no understanding of the Maine woods, especially at 30 below zero in the middle of the winter. He almost certainly would have frozen to death. However he now had to change his plans to avoid any possibility of the loss of human life and this involved risking his own and almost certainly conceding his capture. He cut the fuse to 3 minutes, placed the charge under a bridge support on the Canadian side and listened carefully to be certain there were no trains coming. He lit the fuse and barely got back across the bridge before a huge explosion woke up the entire citizenry of the two towns. Fortunately for the war effort the explosion only slightly damaged the bridge. As Horn was later to concede he did a very poor job of it because his hand and feet were frozen.

At about 2 A.M. Mr. Tague was checking the boiler at the Hotel thinking it may have been the source of the explosion which had shaken his hotel when he heard the hot water running in the bathroom. To his surprise he found Werner Horn, who had checked out only a few hours earlier, running hot water over his hands. “I freeze my hands”, he explained. Tague opened the window, handed Horn some snow and suggested rubbing this on his hands. Horn asked for a room which Tague provided and went to bed. The cause of the explosion was quickly determined and the investigation just as quickly led the authorities to Horn. Well, perhaps not all of the authorities. The local deputy sheriff, George Ross, said he was asleep in his house very near the bridge when, about 1:10, he heard a noise “which I thought was an earthquake, a collision of engines, or a boiler explosion in the heating plant. The noise disturbed me…” He had some difficulty getting back to sleep but managed it and slept until morning when more curious officials had arrived on the scene to arrest Werner Horn.

About 7 in the morning a posse of officials led by the Superintendent of the Maine Central Railroad knocked on Horn’s hotel door and demanded he open it. He obliged and Lt. Horn was arrested with no real resistance. He readily admitted he was responsible for the attempt to blow up the bridge but claimed he was legally not only justified but required as an officer in the German Army to attack the enemy. He rightly pointed out his action was carried out in enemy territory, Canada, where a state of war existed with his country, Germany. U.S. authorities were perplexed and uncertain about Horn’s legal status. The Canadians and English demanded his immediate extradition for trial or, given the outrage in New Brunswick, lynching.

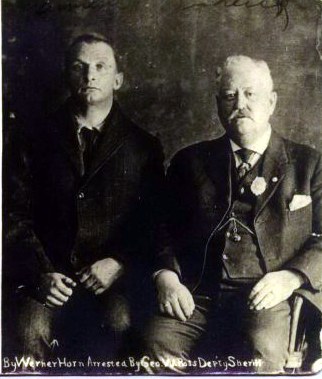

Horn was placed in the custody of the only law enforcement official in Vanceboro, Washington County Deputy George Ross who also operated the local fruit store. Deputy Ross had been only briefly disturbed by the explosion the night before and Horn again confessed to dynamiting the railroad bridge between Vanceboro and McAdam NB just hours earlier in order to disrupt the flow of military supplies to Europe from the Canadian ports of St. John and Halifax. According to the New York Times Deputy Ross didn’t know what to do with Werner Horn and “felt doubtful about detaining him much longer fearing for his own personal liability in the matter.” Ross said he had received no instructions from state or federal authorities, only railroad officials. The Sheriff of Washington County was contacted and told to take the prisoner for safekeeping to Machias which he could only accomplish by a very circuitous route as the most direct route was through Canada. When the Sheriff complained that he had no grounds to charge Horn with any crime in the State of Maine the federal authorities pointed out that many windows had been broken by the explosion in Vanceboro. Thus began a legal battle over Lt. Horn which is perhaps even more interesting than the act of sabotage itself, involving, as it did, treachery by the British Secret Service, diplomatic outrage on the part of all the interested governments, cowardly behavior by the U.S. courts and Werner Horn’s loss of sanity.

On its face it seemed a fairly simple case. Lt. Horn had admitted to detonating 60 pounds of dynamite under an abutment at the Canadian end of the bridge and had been arrested within hours only a short distance from the scene of the crime. The Canadian government, through Britain, had demanded his extradition and the people of Maine and the United States generally were largely sympathetic to the Allied cause. As the locals on both sides of the bridge were in favor of lynching the German, Deputy Ross had become more concerned with each passing hour. His understanding of the legal and diplomatic situation was limited and it is not surprising the deputy did not comprehend the complexity of the problem. The crime was committed in Canada and he was a Washington County deputy with no jurisdiction. He might have gained comfort from the fact that state and federal authorities were equally perplexed.

On February 3, 1915 the United States had not entered the war and was therefore a neutral nation. This status carried significant international legal obligations when dealing with combatants. Lt. Horn had been activated by the German High Command at the beginning of the war and believed it his duty as a German officer to attack enemy military targets wherever possible. It was hard to argue a bridge over which munitions were carried for the purpose of killing German soldiers was not a legitimate military target and Lt. Horn had been very careful to plant the explosives on the Canadian side of the bridge. It was, he claimed, an “Act of War” from which he was immune from extradition to Canada. U.S. authorities were in a quandary because this argument had support under international law and further the extradition treaty between the U.S. and Canada specifically exempted extradition for “political” offenses. The U.S. authorities needed to buy time and Lt. Horn wanted desperately to put as much distance as he could between himself and the Canadian authorities because he truly feared he would be lynched if turned over to the Canadians. Horn agreed to make a deal with Deputy Ross. Because the explosion had broken a few windows on the U.S. side, Lt. Horn became a “willing party” to an agreement to plead to a charge of malicious mischief and accept a 30 day sentence in the Washington County jail in Machias. To his great relief he was immediately transported to Machias via Bangor.

The New York Times headlines of February 4, 1915 fairly well summarize the battle about to begin over the fate of Lt. Horn:

“British Ambassador Moves to Gain Custody of Bridge Wrecker”

“Van Horn Claims Immunity”

“Telegraphs von Bernstoff Requesting Official Aid to Prevent His Surrender to Canada”

“Expects Long Legal Fight”

“Washington Thinks an Appeal to Supreme Court Likely- Nice Question of Political Offense”

The Brits had been most unhappy about the denial of their extradition request and kept the pressure on the U.S. They claimed the German military attaché in Washington, one Captain von Papen and the German Ambassador were responsible for Lt Horn’s actions, not to mention numerous other crimes, plots and unspeakable travesties against England, the U.S. and humanity in general. About a year after the Vanceboro bridge incident von Papen was given safe conduct across the Atlantic by the Brits to allow his return to Germany. This was in exchange, no doubt, for a British subject being allowed safe conduct from Axis held territory. When von Papen’s ship docked in England he was, as agreed, sent along to Germany but with only the clothes on his back. All of his possessions, including official records, were seized by the British Secret Service on the dubious pretext that good conduct applied only to the persons, not their possessions. The howls of protest and anger which emanated from Germany could be heard even over the din of battle on the Western Front but to no avail, the Brits had a treasure trove of intelligence including von Papen’s checkbook. This, they claimed, contained an entry for a $700 payment to Lt Horn just before his attempt to blow up the bridge. The controversy raged for a couple of weeks in the New York Times and other papers but suddenly died for reasons unknown.

In the end the British, or more accurately the Canadians, got their man. Because the United States had entered the war before Lt Horn’s sentence expired he was not released but instead was held in Georgia as an enemy alien. On September 27, 1919 he was brought to New York with a large group of German prisoners being repatriated to Germany, a fate he presumed he was to share. Instead he was taken before a U.S. Commissioner at the request of the British Consul and asked if he had attempted to blow up the Canadian Pacific railroad bridge in McAdam. Always truthful he answered “Yes, I did it in behalf of my country, as an officer of the German Army, in war time.” Horn was unrepresented at the hearing and the request for extradition was quickly granted. Upon his arrival in Canada he was tried, convicted and a sentenced to 10 years to be served in Dorchester Prison in New Brunswick. On July 23, 1921 he was certified insane by physicians at Dorchester prison and returned to Germany. It was a rather sad fate to befall a young man of such undeniable courage and honesty.